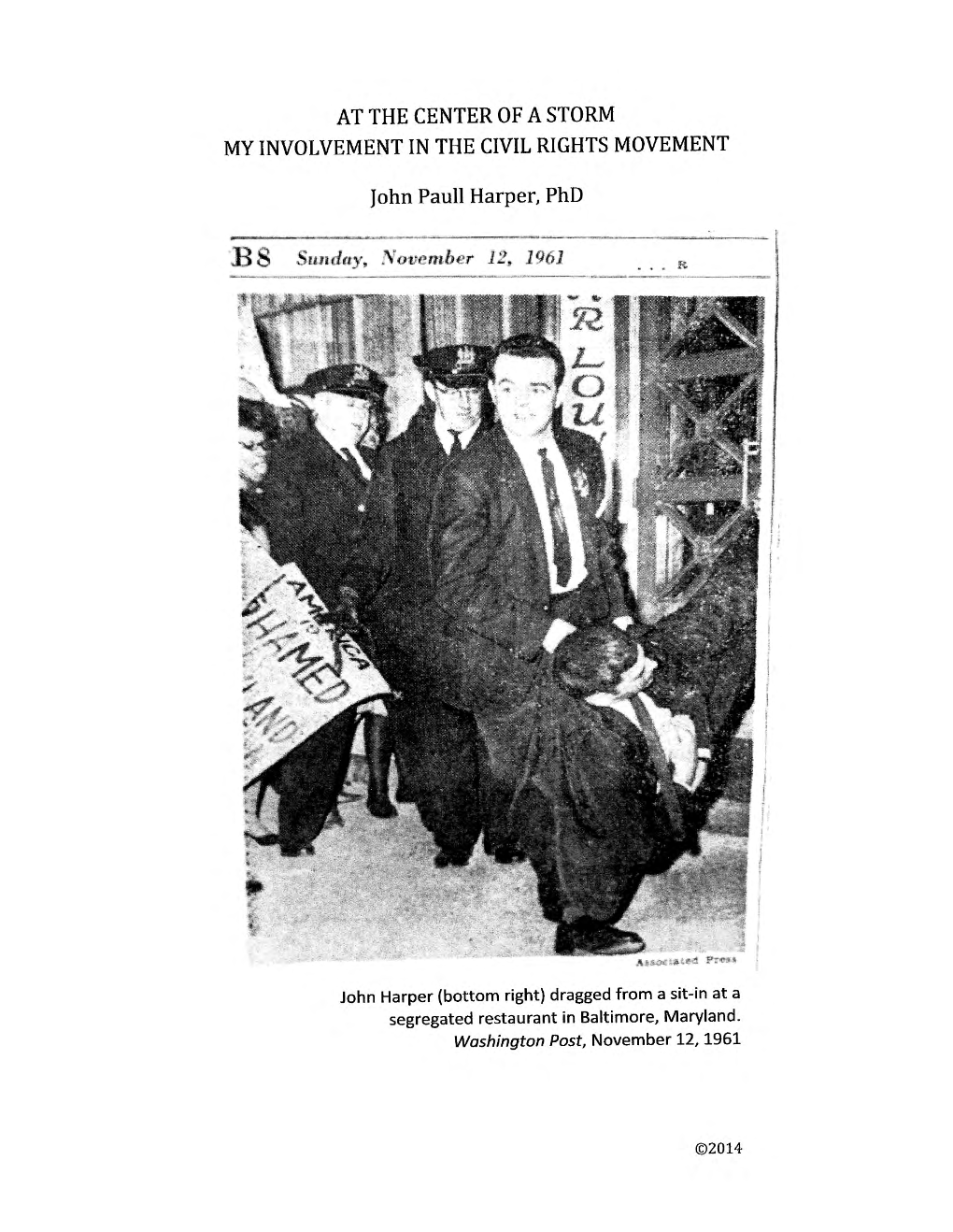

At the Center of a Storm My Involvement in the Civil Rights Movement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Senate 14807 A

1963 C0NGRESSI0NAL RECORD- SENATE 14807 A. James D. Mann, 839 17th ·Street NW., A. Sessions & Caminita, 917 15th Street Washington, D;C, NW., Washington, D.C. SENATE B. National Association of Motor Bus B. Floyd A. Segel, 215 West Oregon Street, Owners, 839 17th Street ·NW., Washington, Milwaukee, Wis. T UESDAY, AUGUST 13, 1963 D.C. A. Clifford Setter, 55 West 44th Street, The Senate met at 12 o'clock meridian, A. Morison, Murphy, Clapp & Abrams, the New York, N.Y. and was called to order by the President Pennsylvania Building, Washington, D.C. B. United States Plywood Corp. pro tempore. B. William S. Beinecke, 114 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. The Chaplain, Rev. Frederick Brown A. Laurence P. Sherfy, 1102 Ring Build Harris, D.D., offered the following ing, Washington, D.C. prayer: A. Raymond Nathan, 1741 DeSales Street B. American Mining Congress, Ring Build NW., Washington, D.C. ing, Washington, D.C. B. Associated Fur Manufacturers, 101 Our Father God, bowing at this way West 30th Street, New York, N.Y. side shrine where spirit with spirit may A. Gerald H. Sherman, 1000 Bender Build meet, we thank Thee for the ministry A. Raymond Nathan, 1741 DeSales Street ing, Washington, D.C. of prayer through whose mystic doors NW., Washington, D.C. B. Association for Advanced Life Under we may escape from the prosaic hum B. Glen Alden Corp., 1740 Broadway, New writing, 1120 Connecticut Avenue NW., drum of "day-by-day-ness" and, lifted to York, N.Y. Washington, D.C. a wider perspective, return illumined and empowered. -

Sandspur, Vol 79 No 04, October 25,1972

University of Central Florida STARS The Rollins Sandspur Newspapers and Weeklies of Central Florida 10-25-1972 Sandspur, Vol 79 No 04, October 25,1972 Rollins College Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-sandspur University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Newspapers and Weeklies of Central Florida at STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Rollins Sandspur by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Rollins College, "Sandspur, Vol 79 No 04, October 25,1972" (1972). The Rollins Sandspur. 1427. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/cfm-sandspur/1427 "The OTHERS" ' ^ r ,+ ~m_ fr<HI* h m See page 2 and page 4. From The We Get Letters Basement Dear Editor: campaign. And, if they did knowaboui- A national poll, taken in early September, they did), they were and are just asbmi It is my hope that Peter's feature on the Scho claimed that 64% of the American electorate devious as many people believed them1 ol for Continuing Studies will shed a bit of light want to re-elect the President for another four on the "other" Rollins-who the people are, why year term. This is a sad situation indeed. Finally, we still have the terriblep^ they are here, how "we" regard them. It seems Surely the American public must understand Vietnam. What it comes down toistfe to me that the Rollins administration has adequ that the President is constantly lying to them tinuation and escalation of a policy j;, ately defined their existence and their program about the national and international scene. -

What's in a Name

What’s In A Name: Profiles of the Trailblazers History and Heritage of District of Columbia Public and Public Charter Schools Funds for the DC Community Heritage Project are provided by a partnership of the Humanities Council of Washington, DC and the DC Historic Preservation Office, which supports people who want to tell stories of their neighborhoods and communities by providing information, training, and financial resources. This DC Community Heritage Project has been also funded in part by the US Department of the Interior, the National Park Service Historic Preservation Fund grant funds, administered by the DC Historic Preservation Office and by the DC Commission on the Arts and Humanities. This program has received Federal financial assistance for the identification, protection, and/or rehabilitation of historic properties and cultural resources in the District of Columbia. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, or disability in its federally assisted programs. If you believe that you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to: Office of Equal Opportunity, U.S. Department of the Interior, 1849 C Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20240.‖ In brochures, fliers, and announcements, the Humanities Council of Washington, DC shall be further identified as an affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities. 1 INTRODUCTION The ―What’s In A Name‖ project is an effort by the Women of the Dove Foundation to promote deeper understanding and appreciation for the rich history and heritage of our nation’s capital by developing a reference tool that profiles District of Columbia schools and the persons for whom they are named. -

District of Columbia Social Studies Pre-K Through Grade 12 Standards

SOCIAL STUDIES District of Columbia Social Studies Pre-K through Grade 12 Standards SOCIAL STUDIES Contents Introduction . 2 Grade 4 — U.S. History and Geography: Making a New Nation . 18 Prekindergarten — People and How They Live . 6 The Land and People before European Exploration . 18 Age of Exploration (15th–16th Centuries). 18 People and How They Live . 6 Settling the Colonies to the 1700s . 19 Economics . 6 The War for Independence (1760–1789) . 20 Time, Continuity, and Change . 7 Geography . 7 Grade 5 — U.S. History and Geography: Westward Expansion Civic Values and Historical Thinking. 7 to the Present . 22 Kindergarten — Living, Learning, and Working Together. 8 The New Nation’s Westward Expansion (1790–1860) . 22 The Growth of the Republic (1800–1860) . 22 Geography . 8 The Civil War and Reconstruction (1860–1877). 23 Historical Thinking . 8 Industrial America (1870–1940) . 24 Civic Values . 8 World War II (1939–1945) . 25 Personal and Family Economics . 9 Economic Growth and Reform in Contempory America Grade 1 — True Stories and Folktales from America (1945–Present) . 26 and around the World . 10 Grades 3–5 — Historical and Social Sciences Analysis Skills . 28 Geography . 10 Chronology and Cause and Effect . 28 Civic Values . 10 Geographic Skills . 28 Earliest People and Civilizations of the Americas . 11 Historical Research, Evidence, and Point of View . 29 Grade 2 — Living, Learning, and Working Now and Long Ago . 12 Grade 6 — World Geography and Cultures . 30 Geography . 12 The World in Spatial Terms . 30 Civic Values . 12 Places and Regions . 30 Kindergarten–Grade 2 — Historical and Social Sciences Human Systems . -

1970 GENERAL ELECTION UNITED STATES SENATOR Republican Richard L

1970 GENERAL ELECTION UNITED STATES SENATOR republican Richard L. Roudebush 29,713 democrat R. Vance Hartke 32,992 SECRETARY OF STATE republican William N. Salin 29,545 democrat Larry Conrad 31,295 AUDITOR OF STATE republican Trudy Slaby Etherton 29,271 democrat Mary Atkins 31,690 TREASURER OF STATE republican John M. Mutz 28,811 democrat Jack New 31,626 SUPERINTENDENT OF PUBLIC INSTRUCTION republican Richard D. Wells 27,952 democrat John J. Loughlin 32,688 CLERK OF SUPREME & APPELLATE COURT republican Kendal E. Matthews 29,108 democrat Billie R. McCullough 31,160 JUDGE OF SUPREME COURT 2ND DISTRICT republican Joseph O. Carson 29,242 democrat Dixon W. Prentice 30,922 JUDGE OF SUPREME COURT 5TH DISTRICT republican Frank V. Dice 28,390 democrat Roger O. DeBruler 31,637 JUDGE APPELLATE COURT 1ST DISTRICT republican Paul H. Buchanan, Jr. 29,401 republican Robert B. Lybrook 28,341 democrat Thomas J. Faulconer 31,084 democrat Jonathan J. Robertson 31,354 JUDGE APPELLATE COURT 2ND DISTRICT republican Gilbert Bruenberg 28,796 republican Alfred J. Pivarnik 28,076 democrat Robert H. Staton 31,165 democrat Charles S. White 31,700 REPRESENTATIVE IN CONGRESS 8TH DISTRICT republican Roger H. Zion 33,915 democrat J. David Huber 28,508 PROSECUTING ATTORNEY republican Rodney H. Grove 30,560 democrat William J. Brune 31,141 JUDGE SUPERIOR COURT republican Alfred A. Kiltz 27,171 republican Claude B. Lynn 26,746 democrat Benjamin E. Buente 33,095 democrat Terry D. Dietsch 35,281 STATE SENATOR - VANDERBURGH, POSEY republican Sidney S. Kramer 29,851 democrat Philip H. Hayes 31,361 STATE REPRESENTATIVES republican John Coates Cox 30,018 republican James D. -

Fighting Injustice

Fighting Injustice by Michael E. Tigar Copyright © 2001 by Michael E. Tigar All rights reserved CONTENTS Introduction 000 Prologue It Doesn’t Get Any Better Than This 000 Chapter 1 The Sense of Injustice 000 Chapter 2 What Law School Was About 000 Chapter 3 Washington – Unemployment Compensation 000 Chapter 4 Civil Wrongs 000 Chapter 5 Divisive War -- Prelude 000 Chapter 6 Divisive War – Draft Board Days and Nights 000 Chapter 7 Military Justice Is to Justice . 000 Chapter 8 Chicago Blues 000 Chapter 9 Like A Bird On A Wire 000 Chapter 10 By Any Means Necessary 000 Chapter 11 Speech Plus 000 Chapter 12 Death – And That’s Final 000 Chapter 13 Politics – Not As Usual 000 Chapter 14 Looking Forward -- Changing Direction 000 Appendix Chronology 000 Afterword 000 SENSING INJUSTICE, DRAFT OF 7/11/13, PAGE 2 Introduction This is a memoir of sorts. So I had best make one thing clear. I am going to recount events differently than you may remember them. I will reach into the stream of memory and pull out this or that pebble that has been cast there by my fate. The pebbles when cast may have had jagged edges, now worn away by the stream. So I tell it as memory permits, and maybe not entirely as it was. This could be called lying, but more charitably it is simply what life gives to each of us as our memories of events are shaped in ways that give us smiles and help us to go on. I do not have transcripts of all the cases in the book, so I recall them as well as I can. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles “Free DC:” the Struggle For

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles “Free D.C.:” The Struggle for Civil, Political, and Human Rights in Washington, D.C., 1965-1979 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Selah Shalom Johnson 2015 © Copyright by Selah Shalom Johnson 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION “Free D.C.:” The Struggle for Civil, Political, and Human Rights in Washington, D.C., 1965-1979 by Selah Shalom Johnson Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor Brenda Stevenson, Chair “Free D.C:” The Struggle for Civil, Political, and Human Rights in Washington, D.C., 1965-1979, illuminates one of the greatest political shortcomings in 20th century America, which was the failure to provide full political enfranchisement for the citizens of Washington, D.C. – the first major American city with a majority African-American population. This project centers on the Free D.C. Movement, a political crusade to fully enfranchise Washingtonians, through grassroots organizing and by pressuring the Federal government to address the political, social, and economic ills that plagued the nation’s capital for nearly a century. Washingtonians’ struggle for full political enfranchisement was one of the most significant goals and significant shortcomings of the 20th century. ii Washington has been an under-researched part of Civil Rights Movement history, even though the city had an instrumental role during this era. My project explores the “Free D.C.” Movement through the lens of residential segregation, employment, and education. I examine how the desire for institutional changes and improvements in these areas helped shape and direct the local movement, and consequently undermined Washington, D.C. -

American Dream Deferred: Black Federal Workers in Washington, Dc, 1941-1981

AMERICAN DREAM DEFERRED: BLACK FEDERAL WORKERS IN WASHINGTON, D.C., 1941-1981 A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History By Frederick W. Gooding, Jr., J.D. Washington, DC June 20, 2013 Copyright 2013 by Frederick W. Gooding, Jr. All Rights Reserved ii AMERICAN DREAM DEFERRED: BLACK FEDERAL WORKERS IN WASHINGTON, D.C., 1941-1981 Frederick W. Gooding, Jr., J.D. Thesis Advisor: Michael Kazin, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This study explores the history of black workers in Washington, D.C.’s federal sector from World War II (WWII) to the early 1980s. Many blacks viewed government employment as a welcome alternative to the limited job prospects and career trajectories available in the hostile and discriminatory private sector. As their numbers in the public sector in Washington increased, African-Americans gained a measure of economic security, elevated their social standing, and increased their political participation, primarily through public sector unions and such civil rights groups as the National Urban League (NUL) and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). However, the growth of racial liberalism in the post-war era did not do away with discrimination in federal employment. In contrast to their white colleagues, black federal workers consistently faced lower wages and slower promotion rates, despite presidential commissions and laws intended to eliminate racial inequities in the workplace. Gradually, black workers improved their status through collective and individual activism, within a context of official support for their rights. -

UCCS Weekly Vi, N12 (November 7, 1972

/ Oor:c.e :E:or.c.e A%:c.erioa **************** Keeping the Olympics Out of Colorado by. Timothy Lange/AFS of holding them. birthday, a time of national there has been a tremendous (Timothy Lange is the Colorado The sharp change in attitude celebrations sure to bring fame change in public attitude. We Daily Editor) marks a deepening concern for and dollars to Colorado. don't need growth now." Colorado's environment and the But soon after the an Lamm and State Senator When it first was announced in manner in which the Winter nouncement that Denver had won Robert Jackson have also May 1970 that Denver, Colorado Games have been promoted in the bid before the International disputed the DOOC's estimates of had won its bid to hold the 1976 Colorado by the Denver Olym Olympics Committee, the op the Games' cost, and point out Winter Olympics, most citizens pics Organizing Committee position began. that DOOC officials first said the greeted the news with satisfaction. (DOOC). The first group to be heard Games would cost $7 million, But now, two-and-a-half years called itself Protect Our Moun then revised that to $14 million, later, polls indicate that come Denver officials worked for tain Environment (POME). and most recently predicted Nov. 7, Coloradans will vote to eight years to get the opportunity POME opposed the DOOC's $34.5 million. "From the tax cut off further state expenditures to hold the '76 Games, which choice of Evergreen-an unin payer standpoint," Lamm says, for the Olympic Games, and coincide with the state's 100th corporated town of 3000 in the "the history of the Olympics over , thereby squelch Denver's chances birthday and the nation's 100th foothills west of Denver-as a site the last 20 years is one of cost for rr.ajor snow events. -

The Art of D.C. Politics: Broadsides, Banners, and Bumper Stickers

Washington History in the Classroom This article, © the Historical Society of Washington, D.C., is provided free of charge to educators, parents, and students engaged in remote learning activities. It has been chosen to complement the DC Public Schools curriculum during this time of sheltering at home in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. “Washington History magazine is an essential teaching tool,” says Bill Stevens, a D.C. public charter school teacher. “In the 19 years I’ve been teaching D.C. history to high school students, my scholars have used Washington History to investigate their neighborhoods, compete in National History Day, and write plays based on historical characters. They’ve grappled with concepts such as compensated emancipation, the 1919 riots, school integration, and the evolution of the built environment of Washington, D.C. I could not teach courses on Washington, D.C. Bill Stevens engages with his SEED Public Charter School history without Washington History.” students in the Historical Society’s Kiplinger Research Library, 2016. Washington History is the only scholarly journal devoted exclusively to the history of our nation’s capital. It succeeds the Records of the Columbia Historical Society, first published in 1897. Washington History is filled with scholarly articles, reviews, and a rich array of images and is written and edited by distinguished historians and journalists. Washington History authors explore D.C. from the earliest days of the city to 20 years ago, covering neighborhoods, heroes and she-roes, businesses, health, arts and culture, architecture, immigration, city planning, and compelling issues that unite us and divide us. -

Washington History in the Classroom

Washington History in the Classroom This article, © the Historical Society of Washington, D.C., is provided free of charge to educators, parents, and students engaged in remote learning activities. It has been chosen to complement the DC Public Schools curriculum during this time of sheltering at home in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. “Washington History magazine is an essential teaching tool,” says Bill Stevens, a D.C. public charter school teacher. “In the 19 years I’ve been teaching D.C. history to high school students, my scholars have used Washington History to investigate their neighborhoods, compete in National History Day, and write plays based on historical characters. They’ve grappled with concepts such as compensated emancipation, the 1919 riots, school integration, and the evolution of the built environment of Washington, D.C. I could not teach courses on Washington, D.C. Bill Stevens engages with his SEED Public Charter School history without Washington History.” students in the Historical Society’s Kiplinger Research Library, 2016. Washington History is the only scholarly journal devoted exclusively to the history of our nation’s capital. It succeeds the Records of the Columbia Historical Society, first published in 1897. Washington History is filled with scholarly articles, reviews, and a rich array of images and is written and edited by distinguished historians and journalists. Washington History authors explore D.C. from the earliest days of the city to 20 years ago, covering neighborhoods, heroes and she-roes, businesses, health, arts and culture, architecture, immigration, city planning, and compelling issues that unite us and divide us. -

"The Whole Nation Will Move": Grassroots Organizing in Harlem and the Advent of the Long, Hot Summers

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses November 2018 "The Whole Nation Will Move": Grassroots Organizing in Harlem and the Advent of the Long, Hot Summers Peter Blackmer University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Politics Commons, Political History Commons, Politics and Social Change Commons, United States History Commons, and the Urban Studies Commons Recommended Citation Blackmer, Peter, ""The Whole Nation Will Move": Grassroots Organizing in Harlem and the Advent of the Long, Hot Summers" (2018). Doctoral Dissertations. 1419. https://doi.org/10.7275/12480028 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/1419 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “THE WHOLE NATION WILL MOVE”: GRASSROOTS ORGANIZING IN HARLEM AND THE ADVENT OF THE LONG, HOT SUMMERS A Dissertation Presented by PETER D. BLACKMER Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY September 2018 W.E.B. DU BOIS DEPARTMENT OF AFRO-AMERICAN STUDIES © Copyright by Peter D. Blackmer 2018