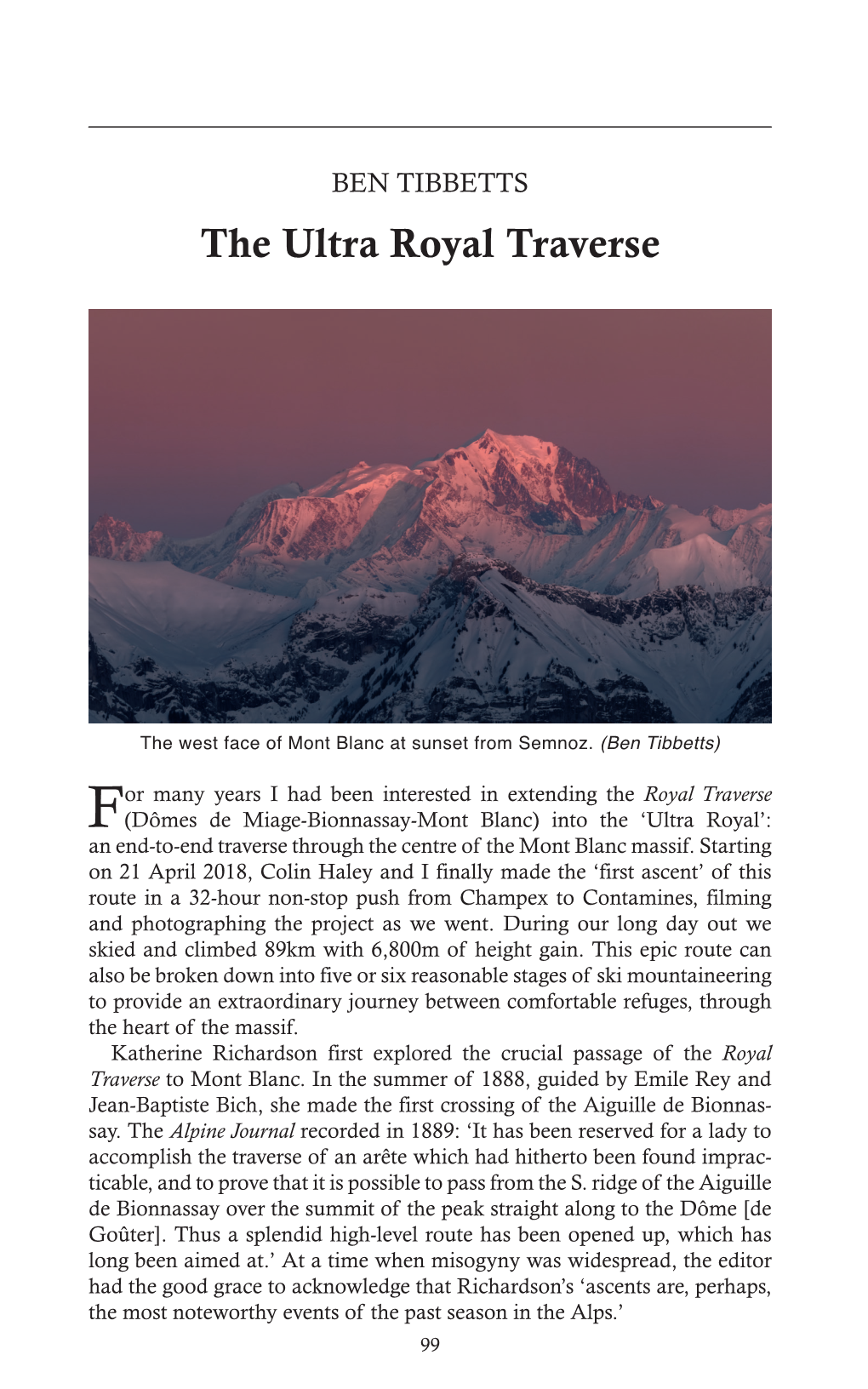

The Ultra Royal Traverse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cíl Všech Horolezccíl Všech Horolezců Na Vrchol Mont Blanc Vede Více Cest

Grandes Jorasses Dent du Géant Aiguille du Midi Mont Blanc du Tacul Mont Maudit Mont Blanc Dôme du Goûter Aiguilles de Bionnassay 4208 m 4013 m 3842 m 4248 m 4465 m 4810 m 4304 m 4052 m Refuge des Refuge des Grands Mulets Refuge du Goûter Refuge de Tête Rousse Cosmiques 3051 m 3835 m 3167 m 3613 m Arête du Dôme La Jonction Plan de l’aiguille ! Uvědomte si nebezpečí Chamonix Nepleťte si obtížnost s nebezpečím. Nejrušnější cesty na Mont Blanc nejsou odborně řečeno nijak Plan de zvlášť náročné. Avšak vyskytují se na nich všechna nebezpečí spojená s tímto prostředím. Dosažení vrcholu Mont Blanc l'Aiguille 7 cest na vrchol Alp Pro snížení rizika začněte nejprve s identifikací nebezpečí terénu a monitorováním aktuálního stavu a možností členů vaší skupiny. Cíl všech horolezcCíl všech horolezců Na vrchol Mont Blanc vede více cest. St-Gervais- 3 les-Bains léphérique Té Nadmořská výška Vyzkoušet některou z méně klasických cest může být zábavné, zvláště v ruš- Pro nás horolezce, kteří kolikrát cestujeme tisíce kilometrů, abychom vylezli na vrchol nějším období. Techničtější pasáže vyžadují velké zkušenosti. Kvůli obtížnosti a Čím výše stoupáte, tím méně je kyslíku. les Houches AHN (akutní horská nemoc) je neustálou hrozbou. Bolest hlavy, Mont Blancu, je to něco víc než jen další vrchol v deníčku. Je to sen, někdy i legenda. Historie naší hlavně kvůli riziku expozice. TMB nespavost, dýchavičnost, nechutenství, pocit ucpaného nosu...hlavní příznaky se mohou objevit již v 3 500 m. vášně je vepsána do jeho svahů. Horlivé snažení, nedotčené svahy a elegantní štíty, přátelství na Nedá se dělat nic jiného, než se vrátit zpět. -

Note on the History of the Innominata Face of Mont Blanc De Courmayeur

1 34 HISTORY OF THE INNOMINATA FACE them difficult but solved the problem by the most exposed, airy and exhilarating ice-climb I ever did. I reckon sixteen essentially different ways to Mont Blanc. I wish I had done them all ! NOTE ON THE ILLUSTRATIONS FIG. 1. This was taken from the inner end of Col Eccles in 1921 during the ascent of Mont Blanc by Eccles' route. Pie Eccles is seen high on the right, and the top of the Aiguille Noite de Peteret just shows over the left flank of the Pie. FIG. 2. This was taken from the lnnominata face in 1919 during a halt at 13.30 on the crest of the branch rib. The skyline shows the Aiguille Blanche de Peteret on the extreme left (a snow cap), with Punta Gugliermina at the right end of what appears to be a level summit ridge but really descends steeply. On the right of the deep gap is the Aiguille Noire de Peteret with the middle section of the Fresney glacier below it. The snow-sprinkled rock mass in the right lower corner is Pie Eccles a bird's eye view. FIG. 3. This was taken at the same time as Fig. 2, with which it joins. Pie Eccles is again seen, in the left lower corner. To the right of it, in the middle of the view, is a n ear part of the branch rib, and above that is seen a bird's view of the Punta lnnominata with the Aiguille Joseph Croux further off to the left. -

4000 M Peaks of the Alps Normal and Classic Routes

rock&ice 3 4000 m Peaks of the Alps Normal and classic routes idea Montagna editoria e alpinismo Rock&Ice l 4000m Peaks of the Alps l Contents CONTENTS FIVE • • 51a Normal Route to Punta Giordani 257 WEISSHORN AND MATTERHORN ALPS 175 • 52a Normal Route to the Vincent Pyramid 259 • Preface 5 12 Aiguille Blanche de Peuterey 101 35 Dent d’Hérens 180 • 52b Punta Giordani-Vincent Pyramid 261 • Introduction 6 • 12 North Face Right 102 • 35a Normal Route 181 Traverse • Geogrpahic location 14 13 Gran Pilier d’Angle 108 • 35b Tiefmatten Ridge (West Ridge) 183 53 Schwarzhorn/Corno Nero 265 • Technical notes 16 • 13 South Face and Peuterey Ridge 109 36 Matterhorn 185 54 Ludwigshöhe 265 14 Mont Blanc de Courmayeur 114 • 36a Hörnli Ridge (Hörnligrat) 186 55 Parrotspitze 265 ONE • MASSIF DES ÉCRINS 23 • 14 Eccles Couloir and Peuterey Ridge 115 • 36b Lion Ridge 192 • 53-55 Traverse of the Three Peaks 266 1 Barre des Écrins 26 15-19 Aiguilles du Diable 117 37 Dent Blanche 198 56 Signalkuppe 269 • 1a Normal Route 27 15 L’Isolée 117 • 37 Normal Route via the Wandflue Ridge 199 57 Zumsteinspitze 269 • 1b Coolidge Couloir 30 16 Pointe Carmen 117 38 Bishorn 202 • 56-57 Normal Route to the Signalkuppe 270 2 Dôme de Neige des Écrins 32 17 Pointe Médiane 117 • 38 Normal Route 203 and the Zumsteinspitze • 2 Normal Route 32 18 Pointe Chaubert 117 39 Weisshorn 206 58 Dufourspitze 274 19 Corne du Diable 117 • 39 Normal Route 207 59 Nordend 274 TWO • GRAN PARADISO MASSIF 35 • 15-19 Aiguilles du Diable Traverse 118 40 Ober Gabelhorn 212 • 58a Normal Route to the Dufourspitze -

British Alpine Ski Traverse 1972 Peter Cliff 13

British Alpine Ski Traverse 1972 Peter Cliff In 1956 the Italian guide Waiter Bonatti traversed the Alps with three others on skis from the JuIian Alps to the French Riviera. This was followed in 1965 by Denis Bertholet and an international party of guides who started near Innsbruck and finished at Grenoble. In 1970 Robert Kittl with three other Austrians completed a very fast crossing in 40 days. The challenge for us was twofold: we were to be the first British party, and whereas the others had been predominantly professional guides we were all amateurs. The route we took was from Kaprun, s of Salzburg, to Gap, which is between Nice and Grenoble. The straight line distance was 400 miles (by comparison the straight line distance for the normal Haute Route between Argentiere and Zermatt is 40 miles), and we ascended at least 120,000 ft excluding uphill transport. It took 49 days including halts. The party was: Alan BIackshaw (leader), Michael de Pret Roose (deputy leader and route Klosters to Zermatt), Fl-Lt Dan Drew RAF (food), Peter Judson (equipment), Dr Hamish Nicol (medical), Lt-Col John Peacock REME (route Chamonix to Gap), Dick Sykes (finance) and myself (route Zermatt to Chamonix). On the first section to the Brenner pass we had with us Waiter Mann, who had been very much involved with the planning ofthe whole Austrian section. Support in the field was provided by Brig Gerry Finch and Major David Gore in a Range Rover. The other people who were closely involved were the members of the BBC TV team who filmed a good part of . -

ALPINE NOTES. Date of the ALPINE CLUB OBITUARY: Election

Alpine Notes . 381 The Triglav 'N. Face' is between 700 and 800 rrL high in t hat portion traversed by the ' Jug' route, and for the first three parts of the route it is almost sheer. Great smooth slabs, occurring in successive series, constitute the special and characteristic difficulty. The climb occupied 16 hours in all. F . S. C. ALPINE NOTES. Date of THE ALPINE CLUB OBITUARY: Election Allport, D . W. • • • • • • • 1875 Colgrove, J. B . • • • • • • • 1876 Morse, Sir George H. • • • • • • 1887 Holmes, .Alfred • • • • • • • 1894 Shea, C. E .. • • • • • • • 1896 Nicholson, L. D . • • • • • • 1902 Candler, H. • • • • • • • 1905 Collin, T. • • • • • • • • 1907 Schofield, J . W. • • • • • • 1907 Drake, Canon F. W. • • • • • • 1908 Kidd, Canon J. H . • • • • • • 1921 Morshead, Lt.-Col. H. T. • • • • • 1922 Painter, A. R. • • • • • • • 1923 Wright, W. A. • • • • • • • 1925 Peto, R . H . K . • • • • • • • 1929 THE CLOSING OF THE ITALIAN ALPS. If a little easier in fre _quented districts during t he height of summer, there are no real signs of improvement in the general situation, which continues to be unsatisfactory. During the C.A.I. Congress at Botzen, the President announced that 18 passes, hitherto closed, would be open between t he Stelvio and Pontebba in 1932. The S.A.C. and letters of t he REv. W. A. B. CooLIDGE. The Librarian of the S.A.C. Central Library, Zurich, requests us to announce that, ' together with the Alpine portion of Mr. Coolidge's library, the S.A.C. has collected during the course of the year, in their library at Zurich, many letters belonging to that distinguished mountaineer. It is true that Mr. -

The Peuterey Ridge

THE PEUTEREY RIDGE THE PEUTEREY RIDGE BY J. NEIL MATHER CHANCE word in Chamonix, when we were both ~without regular companions, led me to join Ian McNaught-Davis in an attempt on the Peuterey Ridge. Although I had not met him previously, Mac was well known to me as a competent rock climber and a fast mover. Arrangements were quickly made and we· were soon en route for Courmayeur by motor-cycle. Some rather sudden thunderstorms delayed our arrival in Cour mayeur and caused us to wait another day before starting the climb. The classic ascent of the Peuterey Ridge attains the crest at the Breche Nord des Dames Anglaises, between the Isolee and the Aiguille Blanche, and traverses the Aiguille Blanche to reach Mont Blanc de Courmayeur via the Grand Pilier d'Angle and the upper reaches of the arete. This route was first done by Obersteiner and Schreiner on 30- 31 July, 1927. A swift party given favourable conditions can traverse Mont Blanc from the Gamba hut within the day, but most parties prefer either to spend a night at the Refuge-bivouac Craveri, a small hut which holds five people and which is situated at the Breche Nord, or to make a more hardy bivouac higher up the ridge. We left the chalets of Fresnay at 12.30 P.M. on August 4, 1952, bound for the refuge. Our way took us by the Gamba hut and proved a most pleasant walk. The hut-book there contained an entry under that day telling of the tragic deaths of John Churchill and J ocelyn Moore in the Eccles bivouac. -

512J the Alpine Journal 2019 Inside.Indd 422 27/09/2019 10:58 I N D E X 2 0 1 9 423

Index 2019 A Alouette II 221 Aari Dont col 268 Alpi Biellesi 167 Abram 28 Alpine Journal 199, 201, 202, 205, 235, 332, 333 Absi 61 Alps 138, 139, 141, 150, 154, 156, 163, 165, 179 Aconcagua 304, 307 Altamirano, Martín 305 Adams, Ansel 178 Ama Dablam 280, 282 Adam Smith, Janet 348 American Alpine Journal 298 Adda valley 170 American Civil War 173 Adhikari, Rabindra 286 Amery, Leo 192 Aemmer, Rudolph 242 Amin, Idi 371 Ahlqvist, Carina 279 Amirov, Rustem 278 Aichyn 65 Ancohuma 242 Aichyn North 65, 66 Anderson, Rab 257 Aiguille Croux 248 Andes 172 Aiguille d’Argentière 101 Androsace 222 Aiguille de Bionnassay 88, 96, 99, 102, 104, 106, Angeles, Eugenio 310 109, 150, 248 Angeles, Macario 310 Aiguille de l’M 148 Angel in the Stone (The) Aiguille des Ciseaux 183 review 350 Aiguille des Glaciers 224 Angsi glacier 60 Aiguille des Grands Charmoz 242 Anker, Conrad 280, 329 Aiguille du Blaitière 183 Annapurna 82, 279, 282, 284 Aiguille du Goûter 213 An Teallach 255 Aiguille du Midi 142, 146, 211, 242 Antoinette, Marie 197 Aiguille du Moine 146, 147 Anzasca valley 167 Aiguille Noire de Peuterey 211 Api 45 Aiguilles Blaitière-Fou 183 Ardang 62, 65 Aiguilles de la Tré la Tête 88 Argentère 104 Aiguilles de l’M 183 Argentière glacier 101, 141, 220 Aiguilles Grands Charmoz-Grépon 183 Argentière hut 104 Aiguilles Grises 242 Arjuna 272 Aiguille Verte 104 Arnold, Dani 250 Ailfroide 334 Arpette valley 104 Albenza 168 Arunachal Pradesh 45 Albert, Kurt 294 Ashcroft, Robin 410 Alborz 119 Askari Aviation 290 Alexander, Hugh 394 Asper, Claudi 222 Allan, Sandy 260, -

One Hundred Years Ago C. A. Russell

88 Piz Bernilla, Ph Scerscell and Piz Roseg (Photo: Swiss atiollal TOl/rist Office) One hundred years ago (with extracts from the 'Alpine Journal') c. A. Russell The weather experienced in many parts of rhe Alps during rhe early months of 1877 was, to say the least, inhospitable. Long unsettled periods alternated with spells of extreme cold and biting winds; in the vicinity of St Morirz very low temperatures were recorded during January. One member of the Alpine Club able to make numerous high-level excur sions during the winter months in more agreeable conditions was D. W. Freshfield, who explored the Maritime Alps and foothills while staying at Cannes. Writing later in the AlpilJe Journal Freshfield recalled his _experiences in the coastal mountains, including an ascent above Grasse. 'A few steps to rhe right and I was on top of the Cheiron, under the lee of a big ruined signal, erected, no doubt, for trigonometrical purposes. It was late in the afternoon, and the sun was low in the western heavens. A wilder view I had never seen even from the greatest heights. The sky was already deepening to a red winter sunset. Clouds or mountains threw here and there dark shadows across earth and sea. "Far our at ea Corsica burst out of the black waves like an island in flames, reflecting the sunset from all its snows. From the sea-level only its mountain- 213 89 AiguiJle oire de Pelllerey (P!JOIO: C. Douglas Mill/er) 214 ONE HU DRED YEARS AGO topS, and these by aid of refraction, overcome the curvature of the globe. -

Alpejskie 4-Tysięczniki

Alpejskie 4-tysięczniki Po zdobyciu kilku 4-ro tysięczników przyszło mi do głowy zrobienie listy (a jakże) i kompletowanie pozostałych szczytów. Na stronie Pettera znalazłem potrzebne informacje. W Alpach jest 51 szczytów o wysokości bezwzględnej powyżej 4000 metrów i wybitności nie mniejszej niż 100 metrów, czyli takich, które pasują do definicji „prawdziwej” góry. W 1994 roku UIAA ogłosiła oficjalną listę aż 82 szczytów czterotysięcznych i te dodatkowe 31 są zamieszczone na poniższej liście jako szczyty „nie ujęte w rankingu” (NR). Istnieje wiele punktów spornych na tej liście. Znajdują się na niej wierzchołki o wybitności zaledwie kilkumetrowej, podczas gdy pominięte są na niej wierzchołki o wybitności kilkudziesięciometrowej. Nie planuję wdawać się w dyskusję co jest „prawdziwą” górą a co nią nie jest. Podobnie jak przy innych projektach, tak i tu chodzi przecież o to, by być w ruchu. Kolorem zielonym oznaczam szczyty przeze mnie zdobyte, natomiast kolorem żółtym te, z którymi żadna próba do tej pory się nie powiodła. Primary Rank Name Height Difficulty factor 01 Mont Blanc 4810 4697 PD 02 Dufourspitze 4634 2165 PD 03 Zumsteinspitze 4563 111 F 04 Signalkuppe 4556 102 F 05 Dom 4545 1018 PD 06 Liskamm (east) 4527 376 AD 07 Weisshorn 4505 1055 AD Primary Rank Name Height Difficulty factor 08 Täschhorn 4490 209 AD 09 Matterhorn 4478 1164 AD- 10 Mont Maudit 4465 162 PD 11 Parrotspitze 4436 136 PD 12 Dent Blanche 4356 897 AD 13 Nadelhorn 4327 206 PD 14 Grand Combin 4314 1517 PD+ 15 Finsteraarhorn 4273 2108 PD 16 Mont Blanc du Tacul 4247 -

U N T E R W E

Unterwegs MONTBLANC Niemand wundert sich im Hochgebirge über abschmelzende Gletscher und Steinschlag. Was seit einigen Jahren am Dach Europas zu beobachten ist, scheint allerdings aus dem Rahmen „normaler“ klimatischer und geologischer Veränderungen in den Alpen zu fal- len und ist in Umfang und Konsequenz nur wenigen bekannt. Warme Sommer und labile Gesteinsschichten setzen dem Montblanc-Massiv erheblich zu. Von ULRICH HIMMLER DER MONARCH WANKT Am 18. Januar 1997 löste ein Felssturz an der Basis der Im September des gleichen Jahres Brenvaflanke des Montblanc brach ein Großteil der Westwand der weiter unten eine verheerende Petit Dru mit solcher Wucht aus, daß der Eislawine aus, die bis ins Val Veni Felssturz noch im weit entfernten Zürich abstürzte und dort zwei Skifahrern das seismographisch gemessen werden Leben kostete. Zufällig konnte der konnte. Klettertouren zwischen der Passagier eines Sessellifts das Ereignis klassischen Magnoneroute und dem mit der Kamera festhalten. Bonattipfeiler sind jetzt lebensgefährlich. Mario Colonel Foto: 30 DAV Panorama Nr. 3/1999 Unterwegs MONTBLANC as Gebiet der Montblanc-Gruppe vom 10.bis 16.Februar 1998 begangen (ED+, Möglichkeit, vom Col Moore aus direkt ab- Tourenwünschen ihrer Klienten um. hat während der Saison 1998 6b,A3).Angesprochen auf die „Versuchung zusteigen und das Zentralcouloir von unten Systematisch bieten sie Gipfel an,die früher durch eine Reihe von Unfall- des Teufels“, antworteten sie sinngemäß: anzugehen,eine höllisch gefährliche Angele- nicht zur Diskussion standen:das Breithorn DDmeldungen von sich Reden ge- „Sicher war es ein Risiko,und sicher größer genheit. Der französische Extremalpinist im Wallis (sehr früher Aufbruch in Cour- macht. Meist bedingt durch schlechtes als bei anderen schwierigen Besteigungen. -

Les Clochers D'arpette

31 Les Clochers d’Arpette Portrait : large épaule rocheuse, ou tout du moins rocailleuse, de 2814 m à son point culminant. On trouve plusieurs points cotés sur la carte nationale, dont certains sont plus significatifs que d’autres. Quelqu’un a fixé une grande branche à l’avant-sommet est. Nom : en référence aux nombreux gendarmes rocheux recouvrant la montagne sur le Val d’Arpette et faisant penser à des clochers. Le nom provient surtout de deux grosses tours très lisses à 2500 m environ dans le versant sud-est (celui du Val d’Arpette). Dangers : fortes pentes, chutes de pierres et rochers à « varapper » Région : VS (massif du Mont Blanc), district d’Entremont, commune d’Orsières, Combe de Barmay et Val d’Arpette Accès : Martigny Martigny-Combe Les Valettes Champex Arpette Géologie : granites du massif cristallin externe du Mont Blanc Difficulté : il existe plusieurs itinéraires possibles, partant aussi bien d’Arpette que du versant opposé, mais il s’agit à chaque fois d’itinéraires fastidieux et demandant un pied sûr. La voie la plus courte et relativement pas compliquée consiste à remonter les pentes d’éboulis du versant sud-sud-ouest et ensuite de suivre l’arête sud-ouest exposée (cotation officielle : entre F et PD). Histoire : montagne parcourue depuis longtemps, sans doute par des chasseurs. L’arête est fut ouverte officiellement par Paul Beaumont et les guides François Fournier et Joseph Fournier le 04.09.1891. Le versant nord fut descendu à ski par Cédric Arnold et Christophe Darbellay le 13.01.1993. Spécificité : montagne sauvage, bien visible de la région de Fully et de ses environs, et donc offrant un beau panorama sur le district de Martigny, entre autres… 52 32 L’Aiguille d’Orny Portrait : aiguille rocheuse de 3150 m d’altitude, dotée d’aucun symbole, mais équipée d’un relais d’escalade. -

Peaks & Glaciers®

Peaks & Glaciers® 2021 JOHN MITCHELL FINE PAINTINGS EST 1931 Peaks & Glaciers® 2021 20th Anniversary Exhibition Catalogue All paintings, drawings and photographs are for sale and are available for viewing from Monday to Friday by prior appointment at: John Mitchell Fine Paintings 17 Avery Row Brook Street London W1K 4BF Catalogue compiled and written by William Mitchell. [email protected] + 44 (0)207 493 7567 www.johnmitchell.net To mark our twentieth Peaks & Glaciers exhibition, a dedicated and 3 richly illustrated book will be published later in the spring of this year. Drawing on two decades of specializing in these paintings, drawings Anneler 43 and rare photographs of the Alps, the anniversary publication will chart some of the highlights that have passed through my hands. The Avanti 16 accompanying essay will attempt to explain – to both veteran followers and newcomers alike- why collectors and readers of these annual Braun 44 catalogues continue to enjoy receiving them and why this author Bright 26 derives such pleasure from sourcing and identifying the pictures that are offered. Above all, it promises to be a beautiful homage to the Alps Calame 24, 38 in a year when many people have been unable to spend time in the Colombi 20, 27 mountains and inhale, in the great climber and author Leslie Stephen’s words, ‘all those lungfuls of fresh air’. Contencin 6, 12, 15, 36, 39, 40, 43 da Casalino 48 Details of the book and how to get a copy will be sent to all Peaks & Glaciers enthusiasts nearer the time. Daures 18 Fourcy 14, 19 There has already been some significant snowfall in many parts of the Alps this winter and, as per every season, it is difficult to know in Grimm 11 advance which areas will receive more than others.