Bourritt's Attempt on Mont Blanc in 1784. T

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

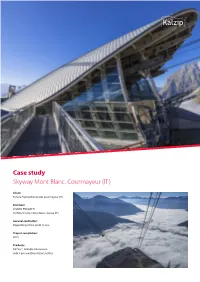

Case Study Skyway Mont Blanc, Courmayeur (IT)

Skyway Mont Blanc Case study Skyway Mont Blanc, Courmayeur (IT) Client: Funivie Monte Bianco AG, Courmayeur (IT) Architect: STUDIO PROGETTI Architect Carlo Cillara Rossi, Genua (IT) General contractor: Doppelmayr Italia GmbH, Lana Project completion: 2015 Products: FalZinc®, foldable Aluminium with a pre-weathered zinc surface Skyway Mont Blanc Mont Blanc, or ‘Monte Bianco’ in Italian, is situated between France and Italy and stands proud within The Graian Alps mountain range. Truly captivating, this majestic ‘White Mountain’ reaches 4,810 metres in height making it the highest peak in Europe. Mont Blanc has been casting a spell over people for hundreds of years with the first courageous mountaineers attempting to climb and conquer her as early as 1740. Today, cable cars can take you almost all of the way to the summit and Skyway Mont Blanc provides the latest and most innovative means of transport. Located above the village of Courmayeur in the independent region of Valle d‘Aosta in the Italian Alps Skyway Mont Blanc is as equally futuristic looking as the name suggests. Stunning architectural design combined with the unique flexibility and understated elegance of the application of FalZinc® foldable aluminium from Kalzip® harmonises and brings this design to reality. Fassade und Dach harmonieren in Aluminium Projekt der Superlative commences at the Pontal d‘Entrèves valley Skyway Mont Blanc was officially opened mid- station at 1,300 metres above sea level. From cabins have panoramic glazing and rotate 2015, after taking some five years to construct. here visitors are further transported up to 360° degrees whilst travelling and with a The project was developed, designed and 2,200 metres to the second station, Mont speed of 9 metres per second the cable car constructed by South Tyrolean company Fréty Pavilion, and then again to reach, to the journey takes just 19 minutes from start to Doppelmayr Italia GmbH and is operated highest station of Punta Helbronner at 3,500 finish. -

4000 M Peaks of the Alps Normal and Classic Routes

rock&ice 3 4000 m Peaks of the Alps Normal and classic routes idea Montagna editoria e alpinismo Rock&Ice l 4000m Peaks of the Alps l Contents CONTENTS FIVE • • 51a Normal Route to Punta Giordani 257 WEISSHORN AND MATTERHORN ALPS 175 • 52a Normal Route to the Vincent Pyramid 259 • Preface 5 12 Aiguille Blanche de Peuterey 101 35 Dent d’Hérens 180 • 52b Punta Giordani-Vincent Pyramid 261 • Introduction 6 • 12 North Face Right 102 • 35a Normal Route 181 Traverse • Geogrpahic location 14 13 Gran Pilier d’Angle 108 • 35b Tiefmatten Ridge (West Ridge) 183 53 Schwarzhorn/Corno Nero 265 • Technical notes 16 • 13 South Face and Peuterey Ridge 109 36 Matterhorn 185 54 Ludwigshöhe 265 14 Mont Blanc de Courmayeur 114 • 36a Hörnli Ridge (Hörnligrat) 186 55 Parrotspitze 265 ONE • MASSIF DES ÉCRINS 23 • 14 Eccles Couloir and Peuterey Ridge 115 • 36b Lion Ridge 192 • 53-55 Traverse of the Three Peaks 266 1 Barre des Écrins 26 15-19 Aiguilles du Diable 117 37 Dent Blanche 198 56 Signalkuppe 269 • 1a Normal Route 27 15 L’Isolée 117 • 37 Normal Route via the Wandflue Ridge 199 57 Zumsteinspitze 269 • 1b Coolidge Couloir 30 16 Pointe Carmen 117 38 Bishorn 202 • 56-57 Normal Route to the Signalkuppe 270 2 Dôme de Neige des Écrins 32 17 Pointe Médiane 117 • 38 Normal Route 203 and the Zumsteinspitze • 2 Normal Route 32 18 Pointe Chaubert 117 39 Weisshorn 206 58 Dufourspitze 274 19 Corne du Diable 117 • 39 Normal Route 207 59 Nordend 274 TWO • GRAN PARADISO MASSIF 35 • 15-19 Aiguilles du Diable Traverse 118 40 Ober Gabelhorn 212 • 58a Normal Route to the Dufourspitze -

Mont Blanc, La Thuile, Italy Welcome

WINTER ACTIVITIES MONT BLANC, LA THUILE, ITALY WELCOME We are located in the Mont Blanc area of Italy in the rustic village of La Thuile (Valle D’Aosta) at an altitude of 1450 m Surrounded by majestic peaks and untouched nature, the region is easily accessible from Geneva, Turin and Milan and has plenty to offer visitors, whether winter sports activities, enjoying nature, historical sites, or simply shopping. CLASSICAL DOWNHILL SKIING / SNOWBOARDING SPORTS & OFF PISTE SKIING / HELISKIING OUTDOOR SNOWKITE CROSS COUNTRY SKIING / SNOW SHOEING ACTIVITIES WINTER WALKS DOG SLEIGHS LA THUILE. ITALY ALTERNATIVE SKIING LOCATIONS Classical Downhill Skiing Snowboarding Little known as a ski destination until hosting the 2016 Women’s World Ski Ski School Championship, La Thuile has 160 km of fantastic ski infrastructure which More information on classes is internationally connected to La Rosiere in France. and private lessons to children and adults: http://www.scuolascilathuile.it/ Ski in LA THUILE 74 pistes: 13 black, 32 red, 29 blue. Longest run: 11 km. Altitude range 2641 m – 1441 m Accessible with 1 ski pass through a single Gondola, 300 meters from Montana Lodge. Off Piste Skiing & Snowboarding Heli-skiing La Thuile offers a wide variety of off piste runs for those looking for a bit more adventure and solitude with nature. Some of the slopes like the famous “Defy 27” (reaching 72% gradient) are reachable from the Gondola/Chairlifts, while many more spectacular ones including Combe Varin (2620 m) , Pont Serrand (1609 m) or the more challenging trek from La Joux (1494 m) to Mt. Valaisan (2892 m) are reached by hiking (ski mountineering). -

512J the Alpine Journal 2019 Inside.Indd 422 27/09/2019 10:58 I N D E X 2 0 1 9 423

Index 2019 A Alouette II 221 Aari Dont col 268 Alpi Biellesi 167 Abram 28 Alpine Journal 199, 201, 202, 205, 235, 332, 333 Absi 61 Alps 138, 139, 141, 150, 154, 156, 163, 165, 179 Aconcagua 304, 307 Altamirano, Martín 305 Adams, Ansel 178 Ama Dablam 280, 282 Adam Smith, Janet 348 American Alpine Journal 298 Adda valley 170 American Civil War 173 Adhikari, Rabindra 286 Amery, Leo 192 Aemmer, Rudolph 242 Amin, Idi 371 Ahlqvist, Carina 279 Amirov, Rustem 278 Aichyn 65 Ancohuma 242 Aichyn North 65, 66 Anderson, Rab 257 Aiguille Croux 248 Andes 172 Aiguille d’Argentière 101 Androsace 222 Aiguille de Bionnassay 88, 96, 99, 102, 104, 106, Angeles, Eugenio 310 109, 150, 248 Angeles, Macario 310 Aiguille de l’M 148 Angel in the Stone (The) Aiguille des Ciseaux 183 review 350 Aiguille des Glaciers 224 Angsi glacier 60 Aiguille des Grands Charmoz 242 Anker, Conrad 280, 329 Aiguille du Blaitière 183 Annapurna 82, 279, 282, 284 Aiguille du Goûter 213 An Teallach 255 Aiguille du Midi 142, 146, 211, 242 Antoinette, Marie 197 Aiguille du Moine 146, 147 Anzasca valley 167 Aiguille Noire de Peuterey 211 Api 45 Aiguilles Blaitière-Fou 183 Ardang 62, 65 Aiguilles de la Tré la Tête 88 Argentère 104 Aiguilles de l’M 183 Argentière glacier 101, 141, 220 Aiguilles Grands Charmoz-Grépon 183 Argentière hut 104 Aiguilles Grises 242 Arjuna 272 Aiguille Verte 104 Arnold, Dani 250 Ailfroide 334 Arpette valley 104 Albenza 168 Arunachal Pradesh 45 Albert, Kurt 294 Ashcroft, Robin 410 Alborz 119 Askari Aviation 290 Alexander, Hugh 394 Asper, Claudi 222 Allan, Sandy 260, -

Alpejskie 4-Tysięczniki

Alpejskie 4-tysięczniki Po zdobyciu kilku 4-ro tysięczników przyszło mi do głowy zrobienie listy (a jakże) i kompletowanie pozostałych szczytów. Na stronie Pettera znalazłem potrzebne informacje. W Alpach jest 51 szczytów o wysokości bezwzględnej powyżej 4000 metrów i wybitności nie mniejszej niż 100 metrów, czyli takich, które pasują do definicji „prawdziwej” góry. W 1994 roku UIAA ogłosiła oficjalną listę aż 82 szczytów czterotysięcznych i te dodatkowe 31 są zamieszczone na poniższej liście jako szczyty „nie ujęte w rankingu” (NR). Istnieje wiele punktów spornych na tej liście. Znajdują się na niej wierzchołki o wybitności zaledwie kilkumetrowej, podczas gdy pominięte są na niej wierzchołki o wybitności kilkudziesięciometrowej. Nie planuję wdawać się w dyskusję co jest „prawdziwą” górą a co nią nie jest. Podobnie jak przy innych projektach, tak i tu chodzi przecież o to, by być w ruchu. Kolorem zielonym oznaczam szczyty przeze mnie zdobyte, natomiast kolorem żółtym te, z którymi żadna próba do tej pory się nie powiodła. Primary Rank Name Height Difficulty factor 01 Mont Blanc 4810 4697 PD 02 Dufourspitze 4634 2165 PD 03 Zumsteinspitze 4563 111 F 04 Signalkuppe 4556 102 F 05 Dom 4545 1018 PD 06 Liskamm (east) 4527 376 AD 07 Weisshorn 4505 1055 AD Primary Rank Name Height Difficulty factor 08 Täschhorn 4490 209 AD 09 Matterhorn 4478 1164 AD- 10 Mont Maudit 4465 162 PD 11 Parrotspitze 4436 136 PD 12 Dent Blanche 4356 897 AD 13 Nadelhorn 4327 206 PD 14 Grand Combin 4314 1517 PD+ 15 Finsteraarhorn 4273 2108 PD 16 Mont Blanc du Tacul 4247 -

Peaks & Glaciers®

Peaks & Glaciers® 2021 JOHN MITCHELL FINE PAINTINGS EST 1931 Peaks & Glaciers® 2021 20th Anniversary Exhibition Catalogue All paintings, drawings and photographs are for sale and are available for viewing from Monday to Friday by prior appointment at: John Mitchell Fine Paintings 17 Avery Row Brook Street London W1K 4BF Catalogue compiled and written by William Mitchell. [email protected] + 44 (0)207 493 7567 www.johnmitchell.net To mark our twentieth Peaks & Glaciers exhibition, a dedicated and 3 richly illustrated book will be published later in the spring of this year. Drawing on two decades of specializing in these paintings, drawings Anneler 43 and rare photographs of the Alps, the anniversary publication will chart some of the highlights that have passed through my hands. The Avanti 16 accompanying essay will attempt to explain – to both veteran followers and newcomers alike- why collectors and readers of these annual Braun 44 catalogues continue to enjoy receiving them and why this author Bright 26 derives such pleasure from sourcing and identifying the pictures that are offered. Above all, it promises to be a beautiful homage to the Alps Calame 24, 38 in a year when many people have been unable to spend time in the Colombi 20, 27 mountains and inhale, in the great climber and author Leslie Stephen’s words, ‘all those lungfuls of fresh air’. Contencin 6, 12, 15, 36, 39, 40, 43 da Casalino 48 Details of the book and how to get a copy will be sent to all Peaks & Glaciers enthusiasts nearer the time. Daures 18 Fourcy 14, 19 There has already been some significant snowfall in many parts of the Alps this winter and, as per every season, it is difficult to know in Grimm 11 advance which areas will receive more than others. -

Alpine Thermal and Structural Evolution of the Highest External Crystalline Massif: the Mont Blanc

TECTONICS, VOL. 24, TC4002, doi:10.1029/2004TC001676, 2005 Alpine thermal and structural evolution of the highest external crystalline massif: The Mont Blanc P. H. Leloup,1 N. Arnaud,2 E. R. Sobel,3 and R. Lacassin4 Received 5 May 2004; revised 14 October 2004; accepted 15 March 2005; published 1 July 2005. [1] The alpine structural evolution of the Mont Blanc, nappes and formed a backstop, inducing the formation highest point of the Alps (4810 m), and of the of the Jura arc. In that part of the external Alps, NW- surrounding area has been reexamined. The Mont SE shortening with minor dextral NE-SW motions Blanc and the Aiguilles Rouges external crystalline appears to have been continuous from 22 Ma until at massifs are windows of Variscan basement within the least 4 Ma but may be still active today. A sequential Penninic and Helvetic nappes. New structural, history of the alpine structural evolution of the units 40Ar/39Ar, and fission track data combined with a now outcropping NW of the Pennine thrust is compilation of earlier P-T estimates and geo- proposed. Citation: Leloup, P. H., N. Arnaud, E. R. Sobel, chronological data give constraints on the amount and R. Lacassin (2005), Alpine thermal and structural evolution of and timing of the Mont Blanc and Aiguilles Rouges the highest external crystalline massif: The Mont Blanc, massifs exhumation. Alpine exhumation of the Tectonics, 24, TC4002, doi:10.1029/2004TC001676. Aiguilles Rouges was limited to the thickness of the overlying nappes (10 km), while rocks now outcropping in the Mont Blanc have been exhumed 1. -

The Alpine Club Library

206 The Alpine Club Library. The entire text of the second edition is revised, rearranged, and rewritten, and the authors have not only simplified the general plan of the guide, but, acting on the advice of the reviewers of the first edition, have added a number of new features, and at the same time have not increased the bulk of the volume. The plan of listing peaks alphabetically within their groups has been retained, and to each peak is added not only the altitude, but the rna p reference number and a key letter indicating its oceanic watershed. It has been considered undesirable to retain the earlier sectional sketch maps, and instead a general key-map has been included. A new feature, noticeably absent from the first edition, is an index of passes with appropriate textual references. A glance at the index of peaks reveals in italics how many mountains in the Rockies are but tenta tively named ; and it is to be hop~ed most emphatically that the decisions of the Geographic Board of Canada, in confirming or revising the suggestions of pioneer mountaineers, will be arrived at with more wisdom and appropriateness, and less regard for passing political fancy, than has been evinced in the recent past. • N. E. 0 . THE ALPINE CLUB LIBRARY. By A. J. MAcKINTOSH. The following works have been added to the Library: • Club Publications . (1) Akad. Alpenclub Bern. 25. · Jahresbericht 1929-30. 9 x 5! : pp. 34 : plates. (2) t\kad. Alpenclub Ziiric~ 34. Jahresbericht. 9 x 6: pp. 43. 1929 (3b) Akad. -

The Open-Air Laboratory of the Grandes Jorasses Glaciers. an Opportunity for Developing Close-Range Remote Sensing Monitoring Systems

EGU21-10675 https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu21-10675 EGU General Assembly 2021 © Author(s) 2021. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. The open-air laboratory of the Grandes Jorasses glaciers. An opportunity for developing close-range remote sensing monitoring systems Daniele Giordan1 and Troilo Fabrizio2 1CNR IRPI, Torino, Italy ([email protected]) 2Safe Mountain Foundation Glaciological phenomena can have a strong impact on human activities in terms of hazards and freshwater supply. Therefore, scientific observation and continuous monitoring are fundamental to investigate their current state and recent evolution. Strong efforts in this field have been spent in the Grandes Jorasses massif (Mont Blanc area), where several break-offs and avalanches from the Planpincieux Glacier and the Whymper Serac (Grandes Jorasses Massif) threatened the Planpincieux hamlet in the past. In the last decade, multiple close-range remote sensing surveys have been conducted to study the glaciers. Two time-lapse cameras monitor the Planpincieux Glacier since 2013. Its surface kinematics is measured with digital image correlation. Image analysis techniques allowed at classifying different instability processes that cause break-offs and at estimating their volume. The investigation revealed possible break-off precursors and a monotonic relationship between glacier velocity and break-off volume, which might help for risk evaluation. A robotised total station monitors the Whymper Serac since 2009. The extreme high-mountain conditions force to replace periodically the stakes of the prism network that are lost. In addition to these permanent monitoring systems, five campaigns with different commercial terrestrial interferometric radars have been conducted between 2013 and 2019. -

Great Rides: Tour Mount Blanc

D E T A I L S WHERE: Mont Blanc massif START/FINISH: Chamonix DISTANCE: 120 miles over fi ve days PICTURES: Jo Gibson THE ALPS | GREAT RIDES Great rides Ready to set off TOUR DU for Chamonix MONT BLANC Last summer, Jo Gibson and three companions circumnavigated the Mont Blanc massif by mountain bike. There were ups and downs… e’re riding the Tour du Mont companies who have tweaked the route to give Do it yourself Blanc,’ I told the table of customers more downhill bang for their buck. W mountain bikers over lunch We based our route on internet research, ALPINE ‘ with our skills instructor. ‘It’s a 120-mile Strava heatmaps, and the availability of BIKING loop around the Mont Blanc massif, mainly refuge accommodation. Chopped into five From May to September, the used by walkers, covering three countries daily stages of at most 32 miles, it seemed accommodation in the area is and ascending over 30,000ft. And it’ll be we would be done by lunchtime. Yet with up to plentiful but it’s best to book unsupported.’ 7,000ft of climbing each day, we had no idea ahead. The nearest airport is The response wasn’t the kudos I had how long we’d be riding. Geneva. Car or train are also hoped for. The instructor asked: ’What options. The biking routes are waymarked and the maps emergency precautions have you got in place?’ SMOKING DISC ROTORS are adequate, but plotting Two months later, cloud cloaked the peaks We set off, climbing into the mist that the route on a GPS device above Chamonix, leaving all but the dirty shrouded the Col du Balme. -

The Ascent of the Matterhorn by Edward Whymper

The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Ascent of the Matterhorn by Edward Whymper This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at http://www.gutenberg.org/license Title: The Ascent of the Matterhorn Author: Edward Whymper Release Date: November 17, 2011 [Ebook 38044] Language: English ***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE ASCENT OF THE MATTERHORN*** ii The Ascent of the Matterhorn iii “THEY SAW MASSES OF ROCKS, BOULDERS, AND STONES, DART ROUND THE CORNER.” THE ASCENT OF THE MATTERHORN BY EDWARD WHYMPER v vi The Ascent of the Matterhorn WITH MAPS AND ILLUSTRATIONS Toil and pleasure, in their natures opposite, are yet linked together in a kind of necessary connection.—LIVY. LONDON JOHN MURRAY, ALBEMARLE STREET 1880 All rights are reserved [v] PREFACE. In the year 1860, shortly before leaving England for a long continental tour, the late Mr. William Longman requested me to make for him some sketches of the great Alpine peaks. At this time I had only a literary acquaintance with mountaineering, and had even not seen—much less set foot upon—a mountain. Amongst the peaks which were upon my list was Mont Pelvoux, in Dauphiné. The sketches that were required of it were to celebrate the triumph of some Englishmen who intended to make its ascent. They came—they saw—but they did not conquer. By a mere chance I fell in with a very agreeable Frenchman who accompanied this party, and was pressed by him to return to the assault. -

The 4000M Peaks of the Alps - Selected Climbs Pdf

FREE THE 4000M PEAKS OF THE ALPS - SELECTED CLIMBS PDF Martin Moran | 382 pages | 01 Jun 2007 | Alpine Club | 9780900523663 | English | London, United Kingdom The m Peaks of the Alps: Selected Climbs - Martin Moran - Google книги Additional criteria were used to deselect or include some points, based on the mountain's overall morphology and mountaineering significance. For example, the Grand Gendarme on the Weisshorn was excluded, despite meeting the prominence criterion as it was simply deemed part of that The 4000m Peaks of the Alps - Selected Climbs ridge. A further 46 additional points of mountaineering significance, such as Pic Eccleswhich did not meet the UIAA's primary selection criteria, were then included within an 'enlarged list'. For a list containing many of the independent mountains of the Alps i. Another, less formal, list of metre alpine mountains, containing only independent peaks with a prominence of over m, and based on an earlier s publications by Richard Goedeke, contains just 51 mountains. They are located in Switzerland 48[Note 1] Italy 38 and France These are either:. Since no exact and formal definition of a 'mountain' exists, the number of metre summits is arbitrary. The topographic prominence is an important factor to decide the official nomination of a summit. The 'Official list' proposed by the UIAA is based not only on prominence but also on other criteria such as the morphology general appearance and mountaineering interest. Summits such as Punta Giordani or Mont Blanc de Courmayeur have much less than the 30 metres minimum prominence criterion but are included in the list because of the other criteria.