Cleveland's Greater University Circle Initiative

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visito Or Gu Uide

VISITOR GUIDE Prospective students and their families are welcome to visit the Cleveland Institute of Music throughout the year. The Admission Office is open Monday through Friday with guided tours offered daily by appointment. Please call (216) 795‐3107 to schedule an appointment. Travel Instructions The Cleveland Institute of Music is approximately five miles directly east of downtown Cleveland, off Euclid Avenue, at the corner of East Boulevard and Hazel Drive. Cleveland Institute of Music 11021 East Boulevard Cleveland, OH 44106 Switchboard: 216.791.5000 | Admissions: 216.795.3107 If traveling from the east or west on Interstate 90, exit the expressway at Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive. Follow Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive south to East 105th Street. Cross East 105th and proceed counterclockwise around the traffic circle, exiting on East Boulevard. CIM will be the third building on the left. Metered visitor parking is available on Hazel Drive. If traveling from the east on Interstate 80 or the Pennsylvania Turnpike, follow the signs on the Ohio Turnpike to Exit 187. Leave the Turnpike at Exit 187 and follow Interstate 480 West, which leads to Interstate 271 North. Get off Interstate 271 at Exit 36 (Highland Heights and Mayfield) and take Wilson Mills Road, westbound, for approximately 7.5 miles (note that Wilson Mills changes to Monticello en route). When you reach the end of Monticello at Mayfield Road, turn right onto Mayfield Road for approximately 1.5 miles. Drive two traffic lights beyond the overpass at the bottom of Mayfield Hill and into University Circle. At the intersection of Euclid Avenue, proceed straight through the traffic light and onto Ford Road, just three short blocks from the junction of East Boulevard. -

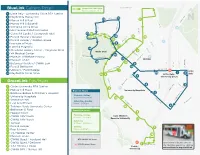

Circlelink Shuttle Map.Pdf

BlueLink Culture/Retail GreenLink AM Spur 6:30-10:00am, M-F 1 Little Italy - University Circle RTA Station 2 Mayfield & Murray Hill 11 3 Murray Hill & Paul 12 11 4 Murray Hill & Edgehill 5 Cornell & Circle Drive 6 UH Cleveland Medical Center 7 Cornell & Euclid / Courtyard Hotel 13 13B 8 Ford & Hessler / Uptown 10 12 10 13A 9 Ford & Juniper / Glidden House 10 Institute of Music 9 13 11 Hazel & Magnolia 14 12 Cleveland History Center / Magnolia West Wade Oval 9 13 VA Medical Center MT SINAI DR 16 14 Museum of Natural History 17 Uptown 15 Museum of Art T S 15 8 16 5 Botanical Garden / CWRU Law 0 8 1 17 Ford & Bellflower E 18 18 Uptown / Ford Garage 7 Little 19 1 2 19 Mayfield & Circle Drive 14 6 Italy 7 GreenLink Eds/Meds 6 3 1 Cedar-University RTA Station 5 2 Murray Hill Road BlueLink Hours University Hospitals 3 Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital 5 Monday—Friday 4 University Hospitals 10:00am—6:00pm 15 4 5 Severance Hall Saturday—Sunday 6 East & Bellflower Noon—6:00pm 7 Tinkham Veale University Center 16 4 8 Bellflower & Ford GreenLink Hours 9 Hessler Court 3 Monday—Friday 10 CWRU NRV South Case Western 6:30am—6:30pm Reserve University 11 CWRU NRV North 17 Saturday 12 Juniper 6:30am—6:00pm T S 13 Ford & Juniper Sunday D 2 N 13A 2 Noon—6:00pm East & Hazel 0 1 13B VA Medical Center E 18 14 Museum of Art 15 CWRU Quad / Adelbert Hall 16 CWRU Quad / DeGrace 1 GetGet real-timereal-time arrshuttleival in infofo vi avia the NextBus app or by visiting 17 1-2-1 Fitness / Veale the NextBus app or by visiting universitycircle.org/circlelinkuniversitycircle.org/circlelink 18 CWRU SRV / Murray Hill GreenLink Schedule Service runs on a continuous loop between CWRU CircleLink is provided courtesy of these North and South campuses, with arrivals sponsoring institutions: approximately every 30 minutes during operating hours and 20-minute peak service (Mon-Fri) Case Western Reserve University between 6:30am - 10:00am and 4:00pm - 6:30pm. -

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation

.NFS Form. 10-900-b ,, .... .... , ...... 0MB No 1024-0018 (Jan. 1987) . ...- United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form NATIONAL REGISTER This form is for use in documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Type all entries. A. Name of Multiple Property Listing_________________________________ Historic and Architectural Resources of the lower Prospect/Huron _____District of Cleveland, Ohio________________________ B. Associated Historic Contexts Commercial Development of Downtown Cleveland, C. Geographical Data___________________________________________________ Downtown Cleveland, Ohio, bounded approximately by Ontario Street, Huron Road NW, and West 9th Street on the west; Lake Brie on the north; and the Innerbelt Jreeway on the east and south* I I See continuation sheet D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in>36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Planning and Evaluation. 2-3-93 _____ Signature of certifying official Date Ohio Historic Preservation Office State or Federal agency and bureau I, hereby, certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluating related properties for listing in the National Register. -

Cleveland Foundation Homer Wadsworth the People's

THE PEOPle’s ENTREPRENEUR Homer C. Wadsworth DIRECTOR OF THE CLEVELAND FOUNDATION 1974 to 1983 Foundations operate best when they work at the growing edge of knowledge, when they uncover and support talent interested in finding new ways of dealing with old problems, when they experiment in the grants they make and the people they support. – Homer C. Wadsworth Text Diana Tittle, with research and writing assistance by Dennis Dooley Copyediting Lisa Semelsberger McGreal Design Stacy Vickroy Lithography Master Printing, Cleveland The People’s Entrepreneur Most of the good things that I have seen in foundations came out of the fact that there were some people at a given time and a given place who had an idea and some guts. – HCW 2 aiting in the reception area of the Cleveland Foundation, Doris Evans prepared herself to be rejected yet again. The pediatrician had conceived of a new not-for- Wprofit enterprise for which she was seeking charitable seed dollars. Along with several other African-American physicians, Dr. Evans wanted to start a health care clinic in Glenville, one of the poorest neighborhoods in the city. This was not to be a typical walk-in clinic, with babies screaming in a dingy reception area while their parents waited hours upon end to be seen by the first available doctor. Such practice flew in the face of the common-sense principle that health problems are more effectively diagnosed and treated by a physician familiar with the medical history of a patient, and Evans, a 31-year-old activist who had dreamed of becoming a doctor since the age of four, envisioned a medical facility that would redress the situation. -

Cleveland in a Nutshell

Cleveland in a Nutshell Cleveland Clinic House Staff Spouse Association The House Staff Spouse Association (HSSA) would like to welcome all new Cleveland Clinic residents, fellows and their families to Cleveland. We can help make this move and new phase of your life a little easier. Cleveland in a Nutshell is a resource we hope you will find useful! The information in this booklet is a compilation of information gathered by past and current Cleveland Clinic spouses. It will help you during your relocation to Cleveland and once you’re settled in your new home. After you arrive in Cleveland, the HSSA is a great way to meet new friends and take part in fun events. Our volunteer group is subsidized by the Cleveland Clinic and organizes affordable social functions for residents, fellows, and their families. From discount sporting event tickets to play dates, we are a social and support network. Membership is free and there are no commitments, except to have fun! Look for our monthly meetings and events in our monthly HSSA newsletter – The Stethoscoop-- which will be mailed to your home in Cleveland and addressed to the resident/fellow. In addition to the newsletter, we also have an online community through Yahoo groups! There are over 100 members and we encourage you to join and become an active member in our community. Please email [email protected] for more details. If you have any questions before you arrive, please don’t hesitate to contact one of our officers: President - Erin Zelin (216)371-9303 [email protected] Vice President - Annie Allen (216)320-1780 [email protected] Stethoscoop Editor - Jennifer Lott (216)291-5941 [email protected] Membership Secretary - MiYoung Wang (216)-291-0921 [email protected] PLEASE NOTE: The information presented here is a compilation of information from past and current CCF spouses. -

+ a Celebration to Remember

FALL/WINTER 2014 NEWS FOR DONORS AND FRIENDS OF THE CLEVELAND FOUNDATION + A CELEBRATION TO REMEMBER: THE COMMUNITY COMMEMORATES OUR 100TH ANNIVERSARY INSIDE: Teresa Metcalf Beasley, Jenniffer Deckard and Bernie Moreno join Board of Directors Welcome to a special issue of Gift of Giving, the magazine for donors and friends of the Cleveland Foundation. We are thrilled so many members of the Cleveland Foundation family were able to join us in celebrating our exciting centennial year as the world’s first community foundation – and what a year it has been! A hallmark of our centennial was doing what we do best – channeling the passions of generous donors into thoughtful and purposeful grantmaking that meets the needs of our residents, enhances the community, and inspires the hearts and minds of Greater Clevelanders. Amid significant excitement, we facilitated a monthly series of public gifts that showcased our history of community support and encouraged Clevelanders to take full advantage of their great city. More than 130,000 residents from across Northeast Ohio and the state participated in these monthly gifts and expressed heartfelt thanks to the Cleveland Foundation for opening the doors to many of our most valued cultural institutions. Our centennial was also marked by two additional centennial legacy grants extended midyear by our board of directors. The first grant, announced in July, was an $8 million lead gift to LAND Studio to support the transformation of Public Square, including naming the south plaza of the new space “Cleveland Foundation Centennial Plaza.” This was followed by a $5 million grant announced in August to The Trust for Public Land that will allow for completion of the “Cleveland Foundation Centennial Trail: Lake Link,” improving public access to Lake Erie. -

Lima APR-08.R5-2 7/9/13 5:04 PM Page 56

CLEVELAND AUGUST 2013_Lima APR-08.R5-2 7/9/13 5:04 PM Page 56 Art, Culture, Dining, and More in… CLEVELAND by Matthew Wexler Photo: Rudy Balasko 56 PASSPORT I AUGUST 2013 CLEVELAND AUGUST 2013_Lima APR-08.R5-2 7/9/13 5:04 PM Page 57 AUGUST 2013 I PASSPORT 57 CLEVELAND AUGUST 2013_Lima APR-08.R5-2 7/9/13 5:04 PM Page 58 cleveland grew up with a chip on my shoulder about Cleveland. Tired of sary, the West Side Market is an architectural wonder designed by Ben- defending my hometown from nomenclatures such as “the mis- jamin Hubbel and W. Dominick Benes. The soaring historic structure is take on the lake,” I eventually gave up and rolled my eyes as if home to more than 100 vendors that feature meats, cheeses, seafood, to say ‘It’s not that bad.’ Well the underdog of the Rust Belt has baked goods, and more. Wander among the stalls, grab a coffee and reinvented itself once again, this time poised to be an interna- homemade pastry, and head to the balcony for a picturesque view of the Itional destination for culture, dining, and innovation. Watch out world, bustling action that becomes denser as the day wears on. Plan your visit Cleveland is back on the map. strategically, as the market is only open four days per week. Of course, ask any Clevelander and they will probably rattle off one Also worth a visit is Ohio City Farm, one of the country’s largest of the city’s various claims to fame. -

Employee Survey

EMPLOYEE SURVEY As part of the Clark-Fulton Together master planning process, we are conducting surveys of the residents, business owners, and people who work within the Study Area Boundary. This survey is the “Employee Survey” designed especially for the people that work within the Clark-Fulton Study Area Boundary (see map below) There are two other separate surveys for “Residents” and for “Business Owners” If you are also a Clark-Fulton Resident, please take the time and fill out the “Resident Survey.” We will be asking general demographic questions, employment information, where do you live and your commute, and general questions about the characteristics of the neighborhood. The Study Area is bounded by I-71 to the east and south, I-90 to the north, and West 44th to the west. The majority of the Study Area falls within the service area for Metro West Community Development Organization, but the portion of the Study Area west of W 25th Street and north of MetroHealth falls within the service area for Tremont West Development Corporation. Before you start the survey, we want to acknowledge the challenging times we are in—do you want to be contacted by a member of our team to help you find the support you need to get through the hardships of COVID-19? □ a. Yes, please contact me about COVID-19 support □ b. No, I am not interested in COVID-19 support GENERAL DEMOGRAPHICS QUESTIONS 1. Year you were born: _________________ 2. Gender: _________________ 3. Race □ a. Black/African American □ b. Caucasian/White □ c. Asian □ d. -

The Gordon Square Arts District in Cleveland's Detroit Shoreway

Cleveland State University EngagedScholarship@CSU Maxine Goodman Levin College of Urban Urban Publications Affairs 3-18-2014 The Gordon Square Arts District in Cleveland’s Detroit Shoreway Neighborhood W Dennis Keating Cleveland State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/urban_facpub Part of the Urban Studies and Planning Commons How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! Repository Citation Keating, W Dennis, "The Gordon Square Arts District in Cleveland’s Detroit Shoreway Neighborhood" (2014). Urban Publications. 0 1 2 3 1162. https://engagedscholarship.csuohio.edu/urban_facpub/1162 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Maxine Goodman Levin College of Urban Affairs at EngagedScholarship@CSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Urban Publications by an authorized administrator of EngagedScholarship@CSU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Gordon Square Arts District in Cleveland’s Detroit Shoreway Neighborhood By W. Dennis Keating Professor and Director, Master of Urban Planning, Design and Development Program Department of Urban Studies, Maxine Goodman Levin College of Urban Affairs Cleveland State University Cleveland, Ohio 44115 Email: [email protected] March, 2014 Beginnings: The Playhouse Square Theaters and the Gordon Square Theaters In 1921, post-World War I Cleveland was a bustling, industrial city that had benefitted from wartime production. Fueled by pre-war immigration from Europe and then the Great Migration north by African-Americans, Cleveland in 1910 was the sixth largest city in the United States. The city’s cultural life was also growing with the opening of the Cleveland Museum of Art in 1916 and the formation of the Cleveland Orchestra in 1918. -

University Circle

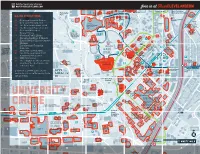

Join in at ThisisCLEVELAND.COM Junior University Magnolia League of Circle Inc. Montes sori The Music Nobby’s Ballpark East Cleveland Clubhouse Settlement Rockefeller Mount Zion Cleveland Hawken School High School Township Cemetery at University Circle M NE AVE Congregational AGN Circle Health BLAI Park Sally and Bob OLIA D E Church RI Services M Gries Center at VE A MAJOR ATTRACTIONS MA Cleveland S A GNOLIA DRIVE Cleveland R University Circle Gestalt T East T E I Friends E 1 Public Library, A Institute 1 N A Cleveland Township 8 S L R Meeting S I T Hough Branch U S T of Cleveland T T O H Cemetery 1 C2 Cleveland Botanical Garden H N 1 E 0 MORE AVE – S KEN K 1 Euclid ENM R D 8 OR T E A 5 VENUE K I T L R Cleveland T C1 IN L H Gate Cleveland History Center E A H G DiSanto E R Louis Stokes S History Center S T J D T Field The Sculpture Center R T Cleveland Veterans B E2 The Cleveland Institute of Art R D and Artists Archives MERIDIAN AVE I R K Affairs Medical E 1 H I E E of the Western Reserve V A Center T E C2 The Cleveland Museum of Art R E R IV I S R D C1 Cleveland Museum of O L University N ZE E E Rockefeller – A 1 D H Circle Police 2 D H A Cleveland AR A D 3 I K Natural History S N O Lagoon R D R ES L Judge Jean A Department S R R T V Institute A D D T AVENUE L E O LBO TA L S D 9 A Murrell Capers U of Music R T 3 C3 ClevelandO Public Library, R O R E Centers for E O R D B E A Tennis Courts V R D S T I IP Dialysis Care Y B Linsalata T S R D L S I N MartinO Luther King, Jr. -

Cleveland Neighborhoods

The Beachland Ballroom COLLINWOOD Bratenahl Cleveland Lakefront 1 Nature Reserve East Gordon Cleveland 90 Park Stokes– 1 10 Windermere East 55th Street GLENVILLE Marina Lke ie AY W E T 3 R O Rockefeller S H S S T. CL A IR – Park 5 AL 0 I 1 R SUPERIOR O E EM M 3 D E N AV Burke Lakefront A E L IR OR AV E A UPERI Cleveland Airport V CL S E T Museum CL S Great Lakes 1 T University of Art S 3 Lake View Science Center 9 HOUGH 7 Circle Cemetery E Little Italy– MIDTOWN MOCA University Circle Cleveland Downtown Heights Playhouse ER AVE University Little FirstEnergy HEST HealthLine Square C AVE Hospitals Stadium JACK EUCLID Italy Cleveland Cleveland Severance Cleveland State CARNEGIE AVE Hall Case Western Casino University Clinic Reserve Whiskey Quicken Loans T S University Island Arena 5 5 FAIRFAX CENTRAL T E Tower S 11 0 QUINCY AVE City– 3 Edgewater Progressive Public E D R CLIFTON BLVD Park Field L Square Red Line L Detroit 90 I LARCHMERE BLVD Cleveland State Line WOODLAND AVE H Shaker D 26 O Square Shoreway O 26 W. 25th St.– W DETROIT AVE edgewater Cleveland West Side Public Theatre Market Ohio City 11 VE Green Line T A Ohio Lakewood DETRO I W. 65th St.– Blue Line Lorain City 490 Shaker KINSMAN BUCKEYE– 81 Tremont 22 Red Line 51 T Square S WOODHILL 6 20 A Christmas 19 K 1 IN 1 cudell SMA Story House N R E T D S CLARK– T 10 5 S 6 FULTON Rocky 5 B 2 W R 90 O River W A NION AVE Mount D U Rocky River 22 81 77 W AY PLEASANT MetroHealth CUYAHOGA A Reservation D 81 V R Hospital E E D STOCKYARDS VALLEY West AV E N N T IN I O A S T S Park R O BROADWAY– -

Cleveland: a Connected City Field Guide © 2014 Ceos for Cities Table of Contents

Cleveland: A Connected City Field Guide © 2014 CEOs for Cities Table of Contents Cleveland State University Levin College of Urban Affairs 1717 Euclid Ave. Cleveland, OH 44115 Offices: Cleveland, Chicago 4 Preface: The Connected City www.ceosforcities.org 6 Cleveland: Becoming Itself ISBN: 978-0-692-23580-5 10 Introduction Written by: Justin Glanville 12 Downtown Cleveland Designed by: Lee Zelenak www.the-beagle.com 18 Waterfronts 24 Euclid Corridor, Campus District and MidTown 30 University Circle 36 St. Clair-Superior 42 Shaker Square and Buckeye The Connected City 48 Detroit-Shoreway “Cities thrive as places where people can easily interact and connect. These connections are of two sorts: the easy interaction 54 Ohio City and Hingetown of local residents and easy connections to the rest of the world. Both internal and external connections are important. 60 Tremont Internal connections help promote the creation of new ideas and make cities work better for their residents. External 66 Special Topics connections enable people and businesses to tap into the global economy. We measure the local connectedness of cities by looking 72 Conclusion at a diverse array of factors including voting, community involvement, economic integration and transit use. Our measures of external connections include foreign travel, the presence of foreign students and broadband Internet use.” — CEOs for Cities, City Vitals 2.0 Cleveland: A Connected City Field Guide 3 The Connected City Each of these theories alone is wrong. A successful city must have all of these elements. It must have compelling public places, creative and educated talent, pathways for economic opportunity and smart technology.