Cleveland: a Connected City Field Guide © 2014 Ceos for Cities Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visito Or Gu Uide

VISITOR GUIDE Prospective students and their families are welcome to visit the Cleveland Institute of Music throughout the year. The Admission Office is open Monday through Friday with guided tours offered daily by appointment. Please call (216) 795‐3107 to schedule an appointment. Travel Instructions The Cleveland Institute of Music is approximately five miles directly east of downtown Cleveland, off Euclid Avenue, at the corner of East Boulevard and Hazel Drive. Cleveland Institute of Music 11021 East Boulevard Cleveland, OH 44106 Switchboard: 216.791.5000 | Admissions: 216.795.3107 If traveling from the east or west on Interstate 90, exit the expressway at Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive. Follow Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive south to East 105th Street. Cross East 105th and proceed counterclockwise around the traffic circle, exiting on East Boulevard. CIM will be the third building on the left. Metered visitor parking is available on Hazel Drive. If traveling from the east on Interstate 80 or the Pennsylvania Turnpike, follow the signs on the Ohio Turnpike to Exit 187. Leave the Turnpike at Exit 187 and follow Interstate 480 West, which leads to Interstate 271 North. Get off Interstate 271 at Exit 36 (Highland Heights and Mayfield) and take Wilson Mills Road, westbound, for approximately 7.5 miles (note that Wilson Mills changes to Monticello en route). When you reach the end of Monticello at Mayfield Road, turn right onto Mayfield Road for approximately 1.5 miles. Drive two traffic lights beyond the overpass at the bottom of Mayfield Hill and into University Circle. At the intersection of Euclid Avenue, proceed straight through the traffic light and onto Ford Road, just three short blocks from the junction of East Boulevard. -

The Cuyahoga River Area of Concern

OHIO SEA GRANT AND STONE LABORATORY The Cuyahoga River Area of Concern Scott D. Hardy, PhD Extension Educator What is an Area of Concern? 614-247-6266 Phone reas of Concern, or AOCs, are places within the Great Lakes region where human 614-292-4364 Fax [email protected] activities have caused serious damage to the environment, to the point that fish populations and other aquatic species are harmed and traditional uses of the land Aand water are negatively affected or impossible. Within the Great Lakes, 43 AOCs have been designated and federal and state agencies, under the supervision of local advisory committees, are working to clean up the polluted sites. Ohio Sea Grant Cuyahoga River AOC College Program Who determines if there 1314 Kinnear Rd. is an Area of Concern? Columbus, OH 43212 614-292-8949 Office A binational agreement between the United States 614-292-4364 Fax and Canada called the Great Lakes Water Quality ohioseagrant.osu.edu Agreement (GLWQA) determines the locations Ohio Sea Grant, based at of AOCs throughout the Great Lakes. According The Ohio State University, to the GLWQA, each of the AOCs must develop is one of 33 state programs in the National Sea Grant a Remedial Action Plan (RAP) that identifies all College Program of the of the environmental problems (called Beneficial National Oceanic and Use Impairments, or BUIs) and their causes. Local Atmospheric Administration environmental protection agencies must then (NOAA), Department of develop restoration strategies and implement them, Commerce. Ohio Sea Grant is supported by the Ohio monitor the effectiveness of the restoration projects Board of Regents, Ohio and ultimately show that the area has been restored. -

Cuyahoga County Urban Tree Canopy Assessment Update 2019

Cuyahoga County Urban Tree Canopy Assessment Update 2019 December 12, 2019 CUYAHOGA COUNTY URBAN TREE CANOPY ASSESSMENT \\ 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS 03 Why Tree Canopy is Important 03 Project Background 03 Key Terms 04 Land Cover Methodology 05 Tree Canopy Metrics Methodology 06 Countywide Findings 09 Local Communities 14 Cleveland Neighborhoods 18 Subwatersheds 22 Land Use 25 Rights-of-Way 28 Conclusions 29 Additional Information PREPARED BY CUYAHOGA COUNTY PLANNING COMMISSION Daniel Meaney, GISP - Information & Research Manager Shawn Leininger, AICP - Executive Director 2079 East 9th Street Susan Infeld - Special Initiatives Manager Suite 5-300 Kevin Leeson - Planner Cleveland, OH 44115 Robin Watkins - GIS Specialist Ryland West - Planning Intern 216.443.3700 www.CountyPlanning.us www.facebook.com/CountyPlanning www.twitter.com/CountyPlanning 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS CUYAHOGA COUNTY URBAN TREE CANOPY ASSESSMENT \\ 2019 Why Tree Canopy is Important Tree canopy is the layer of leaves, branches, and stems of trees that cover the ground when viewed from above. Tree canopy provides many benefits to society including moderating climate, reducing building energy use and atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2), improving air and water quality, mitigating rainfall runoff and flooding, enhancing human health and social well-being and lowering noise impacts (Nowak and Dwyer, 2007). It provides wildlife habitat, enhances property values, and has aesthetic impacts to an environment. Establishing a tree canopy goal is crucial for communities seeking to improve their natural environment and green infrastructure. A tree canopy assessment is the first step in this goal setting process, showing the amount of tree canopy currently present as well as the amount that could theoretically be established. -

Fourth Quarter

Fourth Quarter December 2015 Table of Contents Letter to the Board of Trustees .......................................................... 1 Financial Analysis ................................................................................ 2 Critical Success Factors ...................................................................... 14 DBE Participation/Affirmative Action ................................................ 18 Engineering/Construction Program .................................................. 22 2 From the CEO RTA “Connects the Dots” and also connects the region with opportunities. It was an honor to represent RTA at the ribbon-cutting for the Flats East Bank project that relies on RTA to transport their visitors and their workers to this new world-class waterfront attraction. RTA also cut the ribbon on its new Lee/Van Aken Blue Line Rail Station in Shaker Heights. This modern, safe and ADA accessible station will better connect residents to all the region has to offer. Our hard work throughout the year did not go unnoticed. RTA received accolades by way of Metro Magazine’s Innovative Solutions Award in the area of Safety for taking an aggressive approach to increase operator safety and improving driving behavior and creating a safer experience for transit riders with the use of DriveCam. Speaking of hard work, it truly paid off when RTA Board Member Valerie J. McCall was elected Chair of the American Public Transportation Association. RTA is proud of this accomplishment. Not only does this bring positive attention to Greater Cleveland RTA, but this allows Chair McCall to help shape what the future of the industry will be. RTA is certainly the only transit system in the nation to have two APTA Chairs (past and present) serving on its Board of Trustees. Congratulations Valarie J. McCall and George Dixon!!! During the quarter, RTA received the Silver Commitment to Excellence from The Partnership for Excellence, recognizing the Authority's continued efforts toward obtaining the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Award. -

City Record Official Publication of the Council of the City of Cleveland

The City Record Official Publication of the Council of the City of Cleveland September the Fourth, Two Thousand and Nineteen The City Record is available online at Frank G. Jackson www.clevelandcitycouncil.org Mayor Kevin J. Kelley President of Council Containing PAGE Patricia J. Britt City Council 3 City Clerk, Clerk of Council The Calendar 3 Board of Control 3 Ward Name Civil Service 5 1 Joseph T. Jones Board of Zoning Appeals 5 2 Kevin L. Bishop Board of Building Standards 3 Kerry McCormack and Building Appeals 6 4 Kenneth L. Johnson, Sr. Public Notice 6 5 Phyllis E. Cleveland Public Hearings 6 6 Blaine A. Griffin City of Cleveland Bids 6 7 Basheer S. Jones Adopted Resolutions and Ordinances 8 8 Michael D. Polensek Committee Meetings 8 9 Kevin Conwell Index 8 10 Anthony T. Hairston 11 Dona Brady 12 Anthony Brancatelli 13 Kevin J. Kelley 14 Jasmin Santana 15 Matt Zone 16 Brian Kazy 17 Martin J. Keane Printed on Recycled Paper DIRECTORY OF CITY OFFICIALS CITY COUNCIL – LEGISLATIVE DEPT. OF PUBLIC SAFETY – Michael C. McGrath, Director, Room 230 President of Council – Kevin J. Kelley DIVISIONS: Animal Control Services – John Baird, Interim Chief Animal Control Officer, 2690 West 7th Ward Name Residence Street 1 Joseph T. Jones...................................................4691 East 177th Street 44128 Correction – David Carroll, Interim Commissioner, Cleveland House of Corrections, 4041 Northfield 2 Kevin L. Bishop...............................................11729 Miles Avenue, #5 44105 Rd. 3 Kerry McCormack................................................1769 West 31st Place 44113 Emergency Medical Service – Nicole Carlton, Acting Commissioner, 1708 South Pointe Drive 4 Kenneth L. Johnson, Sr. -

For Immediate Release

For Immediate Release Contact: Melisa Freilino Office 216-377-1339 Cell 216-392-4528 [email protected] www.portofcleveland.com PORT OF CLEVELAND UNVEILS PLANS FOR EXPRESS OCEAN FREIGHT SERVICE TO EUROPE Cleveland-Europe Express will be the only scheduled international container service on the Great Lakes CLEVELAND, OH- The Port of Cleveland unveiled plans today to start a regularly scheduled express freight shipping service between the Cleveland Harbor and Europe, starting in April. The Cleveland-Europe Express Ocean Freight Service will be the only scheduled international container service on the Great Lakes. “Currently, local manufacturers use East Coast ports to ship goods to Europe, incurring additional rail and truck costs along the way,” said Will Friedman, president & CEO of the Port of Cleveland. “The Cleveland Europe-Express will allow local companies to ship out of their own backyards, simplifying logistics and reducing shipping costs.” The service will be the fastest and greenest route between Europe and North America’s heartland, allowing regional companies to ship their goods up to four days faster than using water, rail, and truck routes via the U.S. East Coast ports. The Cleveland-Europe Express is estimated to carry anywhere from 250,000 to 400,000 tons of cargo per year. This volume equates to approximately 10-15% of Ohio’s trade with Europe. “This service will be a game changer for manufacturers in the region, keeping shipping dollars local, while opening our shores to the global market in a new way,” Friedman said. Marc Krantz, chairman of the Port of Cleveland Board, said the organization pursued the express service to meets the Port’s strategic initiatives by growing the Port’s maritime business, increasing the Port’s financial stability, and increasing regional trade opportunities on behalf of Northeast Ohio companies. -

Sheffia Randall Dooley Actress/Singer/Director AEA

Sheffia Randall Dooley Actress/Singer/Director AEA 3017 Joslyn Rd. Hair: Black Cleveland, Ohio 44111 Eyes:Brown (216)502-0417 Voice: Mezzo- Soprano [email protected] Theatre- Directing Fences, AD Karamu House Jiminirising Cleveland Public Theatre/ Entry Point Sister Act Karamu House The Book of Grace Cleveland Public Theatre Napoleon of the Nile Cleveland Public Theatre/ Black Box Aladdin Karamu House Sister Cities Baldwin Wallace College Theatre- Acting Simply Simone Nina 4 Karamu House The Colored Museum Topsy Washington Karamu House, One Voice Dontrell, Who Kissed the Sea Sophia Jones (Mom) Cleveland Public Theatre The Loush Sisters Butter Rum (reoccurring) Cleveland Public Theatre Ruined Mama Nadi Karamu House Open Mind Firmament Aoife Cleveland Public Theatre Caroline, or Change Caroline Karamu House w/ Dobama The Crucible Tituba Great Lakes Theatre Festival Pulp Bing Cleveland Public Theatre Our Town Mrs. Webb Cleveland Public Theatre Respect: A Musical Journey U/S Rosa, Eden (roles perf.) Playhouse Square, Hanna Theatre Community Engagement and Education Playhouse Square Community Engagement and Education Assistant Director Karamu House Cultural Arts Education and Outreach Director Cleveland Municipal School District All City Arts Program Theatre Director Cleveland Playhouse Summer Academy Artist-Instructor The Musical Theatre Project Master Artist in Residence Great Lakes Theater Festival School Residency Program Actor/ Teacher Cleveland Public Theatre Brick City and STEP programs Artist-Instructor/ Director Kaiser Permanente Educational Theatre Programs Actor/ Director Video/ Voice Overs YMCA Commercial Mom Adcom Communications Ask Gilby Izzy Belle Akron Public Schools Mending Spirits Featured Voice Over Moongale Productions Bus Safety Video Bus Driver Avatar Productions Allied Human Resource Video Alcohol Avatar Productions ISG Human Resource Video Featured Employee OSV Studios Spike Live! Aramark Show Trainer Julie Zakarak Productions Training Cleveland Play House Directors Gym- Laura Kepley, Robert Fleming Baldwin-Wallace College: B.A. -

Circlelink Shuttle Map.Pdf

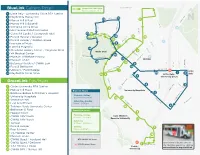

BlueLink Culture/Retail GreenLink AM Spur 6:30-10:00am, M-F 1 Little Italy - University Circle RTA Station 2 Mayfield & Murray Hill 11 3 Murray Hill & Paul 12 11 4 Murray Hill & Edgehill 5 Cornell & Circle Drive 6 UH Cleveland Medical Center 7 Cornell & Euclid / Courtyard Hotel 13 13B 8 Ford & Hessler / Uptown 10 12 10 13A 9 Ford & Juniper / Glidden House 10 Institute of Music 9 13 11 Hazel & Magnolia 14 12 Cleveland History Center / Magnolia West Wade Oval 9 13 VA Medical Center MT SINAI DR 16 14 Museum of Natural History 17 Uptown 15 Museum of Art T S 15 8 16 5 Botanical Garden / CWRU Law 0 8 1 17 Ford & Bellflower E 18 18 Uptown / Ford Garage 7 Little 19 1 2 19 Mayfield & Circle Drive 14 6 Italy 7 GreenLink Eds/Meds 6 3 1 Cedar-University RTA Station 5 2 Murray Hill Road BlueLink Hours University Hospitals 3 Rainbow Babies & Children’s Hospital 5 Monday—Friday 4 University Hospitals 10:00am—6:00pm 15 4 5 Severance Hall Saturday—Sunday 6 East & Bellflower Noon—6:00pm 7 Tinkham Veale University Center 16 4 8 Bellflower & Ford GreenLink Hours 9 Hessler Court 3 Monday—Friday 10 CWRU NRV South Case Western 6:30am—6:30pm Reserve University 11 CWRU NRV North 17 Saturday 12 Juniper 6:30am—6:00pm T S 13 Ford & Juniper Sunday D 2 N 13A 2 Noon—6:00pm East & Hazel 0 1 13B VA Medical Center E 18 14 Museum of Art 15 CWRU Quad / Adelbert Hall 16 CWRU Quad / DeGrace 1 GetGet real-timereal-time arrshuttleival in infofo vi avia the NextBus app or by visiting 17 1-2-1 Fitness / Veale the NextBus app or by visiting universitycircle.org/circlelinkuniversitycircle.org/circlelink 18 CWRU SRV / Murray Hill GreenLink Schedule Service runs on a continuous loop between CWRU CircleLink is provided courtesy of these North and South campuses, with arrivals sponsoring institutions: approximately every 30 minutes during operating hours and 20-minute peak service (Mon-Fri) Case Western Reserve University between 6:30am - 10:00am and 4:00pm - 6:30pm. -

Theatre Facts 2017

THEATRE FACTS 2017 THEATRE COMMUNICATIONS GROUP’S REPORT ON THE FISCAL STATE OF THE U.S. PROFESSIONAL NOT-FOR-PROFIT THEATRE FIELD By Zannie Giraud Voss, Glenn B. Voss, and Lesley Warren, SMU DataArts and Ilana B. Rose and Laurie Baskin, Theatre Communications Group x,QWURGXFWLRQ x([HFXWLYH6XPPDU\ x7KH8QLYHUVH x7UHQG7KHDWUHV (DUQHG,QFRPH $WWHQGDQFH7LFNHWDQG3HUIRUPDQFH7UHQGV &RQWULEXWHG,QFRPH ([SHQVHVDQG&KDQJHLQ8QUHVWULFWHG1HW$VVHWV &81$ %DODQFH6KHHW 7HQ<HDU7UHQG7KHDWUHV x3URILOHG7KHDWUHV (DUQHG,QFRPH &RQWULEXWHG,QFRPH ([SHQVHVDQG&81$ %XGJHW*URXS6QDSVKRW(DUQHG,QFRPH %XGJHW*URXS6QDSVKRW$WWHQGDQFH7LFNHWVDQG3HUIRUPDQFHV %XGJHW*URXS6QDSVKRW&RQWULEXWHG,QFRPH %XGJHW*URXS6QDSVKRW([SHQVHVDQG&81$ %XGJHW*URXS6QDSVKRW%DODQFH6KHHW x&RQFOXVLRQ x0HWKRGRORJ\ x3URILOHG7KHDWUHV &RYHUSKRWRFUHGLWV Top row (left to right): Bottom right (left to right): x 7KHFDVWLQ.DUDPX+RXVH¶VSURGXFWLRQRIYou Can’t Take It x -DPHV'RKHUW\DQG.LD\OD5\DQQLQ6WHHS7KHDWUH¶VSURGXFWLRQRI With YouE\0RLVHVDQG.DXIPDQGLUHFWHGE\)UHG6WHUQIHOG3KRWR HookmanE\/DXUHQ<HHGLUHFWHGE\9DQHVVD6WDOOLQJ3KRWRE\/HH E\0DUN+RUQLQJ 0LOOHU x .DUWKLN6ULQLYDVDQ$QMDOL%KLPDQLDQG3LD6KDKLQ6RXWK&RDVW x (PLO\.XURGD :LOOLDP7KRPDV+RGJVRQLQWKH7KHDWUH:RUNV 5HSHUWRU\¶VSURGXFWLRQRIOrange E\$GLWL%UHQQDQ.DSLOGLUHFWHGE\ 6LOLFRQ9DOOH\¶VSURGXFWLRQRICalligraphy E\%\9HOLQD+DVX+RXVWRQ -HVVLFD.XE]DQVN\3KRWRE\'HERUD5RELQVRQ6&5 'LUHFWHGE\/HVOLH0DUWLQVRQ3KRWRE\.HYLQ%HUQH Second row (left to right): Bottom left (top to bottom): x -HVVLHH'DWLQRDQG-DVRQ.RORWRXURVLQ*HYD VZRUOGSUHPLHUH x 0DLQ6WUHHW7KHDWHU¶VSURGXFWLRQRIThe Grand ConcourseE\+HLGL -

Exploring Cleveland Arts, Culture, Sports, and Parks

ACRL 2019 Laura M. Ponikvar and Mark L. Clemente Exploring Cleveland Arts, culture, sports, and parks e’re all very excited to have you join us mall and one of Cleveland’s most iconic W April 10–13, 2019, in Cleveland for the landmarks. It has many unique stores, a ACRL 2019 conference. Cleveland’s vibrant food court, and gorgeous architecture. arts, cultural, sports, and recreational scenes, • A Christmas Story House and Mu- anchored by world-class art museums, per- seum (http://www.achristmasstoryhouse. forming arts insti- com) is located tutions, music ven- in Cleveland’s ues, professional Tremont neigh- sports teams, his- borhood and was toric landmarks, the actual house and a tapestry of seen in the iconic city and national film, A Christmas parks, offer im- Story. It’s filled mense opportuni- with props and ties to anyone wanting to explore the rich costumes, as well as some fun, behind- offerings of this diverse midwestern city. the-scenes photos. • Dittrick Medical History Center Historical museums, monuments, (http://artsci.case.edu/dittrick/museum) and landmarks is located on the campus of Case Western • Cleveland History Center: A Museum Reserve University and explores the history of the Western Reserve Historical Society of medicine through exhibits, artifacts, rare (https://www.wrhs.org). The Western Re- books, and more. serve Historical Society is the oldest existing • Dunham Tavern Museum (http:// cultural institution in Cleveland with proper- dunhamtavern.org) is located on Euclid ties throughout the region, but its Cleveland Avenue, and is the oldest building in Cleve- History Center museum in University Circle is land. -

Cleveland Located in a Federally-Designated Marion Building Opportunity Zone 1276 W

NEW REDEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY IN THE HEART OF DOWNTOWN CLEVELAND LOCATED IN A FEDERALLY-DESIGNATED MARION BUILDING OPPORTUNITY ZONE 1276 W. 3RD ST. CLEVELAND, OHIO PROPERTY HIGHLIGHTS • 104,698-square-foot, seven-story building • Excellent location in the heart of the Historic Warehouse District, Cleveland’s original “live-work-play” neighborhood, with trendy loft-style apartments and condos, historic office buildings and numerous nightlife and dining options all within a short walk. • Within walking distance to the Flats East Bank, Public Square and North Coast Harbor • Built in 1913 • Immediate access to Route 2/Cleveland Memorial Shoreway SALE PRICE • $8 MILLION ($80/SF) • Accepting qualified offers by August 1st, to allow buyer time to apply for the Ohio State Historic Tax Credit (deadline September 30, 2019). For more information, contact our licensed real estate salespersons: Terry Coyne Richard Sheehan Vice Chairman Managing Director 216.453.3001 216.453.3032 [email protected] [email protected] ngkf.com/cleveland Newmark Knight Frank • 1350 Euclid Avenue, Suite 300 • Cleveland, Ohio 44115 The information contained herein has been obtained from sources deemed reliable but has not been verified and no guarantee, warranty or representa- tion, either express or implied, is made with respect to such information. Terms of sale or lease and availability are subject to change or withdrawal without notice. LOWER LEVEL 1 Floor Plans MARION BUILDING 1276 W. 3RD ST. LowerTypical Level: Floor 13,086 Plates SF and Lower Leevel CLEVELAND, OHIO NORTH First Floor: 13,086 SF Typical Floor Plate (Floors 2-7): 13,086 SF For more information, contact our licensed real estate salespersons: Terry Coyne Richard Sheehan Vice Chairman Managing Director 216.453.3001 216.453.3032 [email protected] [email protected] ngkf.com/cleveland MARION BUILDING 1276 W. -

The Travelin' Grampa

The Travelin’ Grampa Touring the U.S.A. without an automobile Focus on fast, safe, convenient, comfortable, cheap travel, via public transit. Vol. 3, No. 12, December 2010 This house where the 1983 classic film A Christmas Story was shot still stands in Cleveland and has been visited by more than 100,000 tourists. The RTA #81 bus goes there from downtown. Classic film’s hero’s home really exists The home of Ralphie Parker, the boy hero of the classic movie A Christmas Story, is on Rowley Avenue in Cleveland, Ohio, not on Cleveland Street in some fictional town in Indiana., where author Jean Shepherd had placed it in a story he wrote. Shepherd grew up in Hammond, Indiana, where he graduated from high school and worked as a mail carrier and steel worker. Later, he became a radio broadcaster in Cincinnati, Philadelphia and New York. Grampa remembers listening to him on station KYW and chucking at his tall tales. Shepherd also wrote short stories, among them A Christmas Story. The movie’s producer looked at a half dozen cities and towns and decided to shoot its exterior scenes in Cleveland, because Higbee's Department Store there was willing to cooperate in the film’s production. It’s mere coincidence that the name of the street in Hammond where Shepherd grew up was Cleveland Street. 1 Pictures credit: A Christmas Story House Museum; Jennie Moore Cray. ‘Christmas Story’ house in Cleveland. Grampa’s granddaughters and leg lamp. You & grandkids can explore ‘A Christmas Story’ house Restored to its movie splendor, the house in the merry A Christmas Story film is open to the public all year around, but not on Christmas Day.