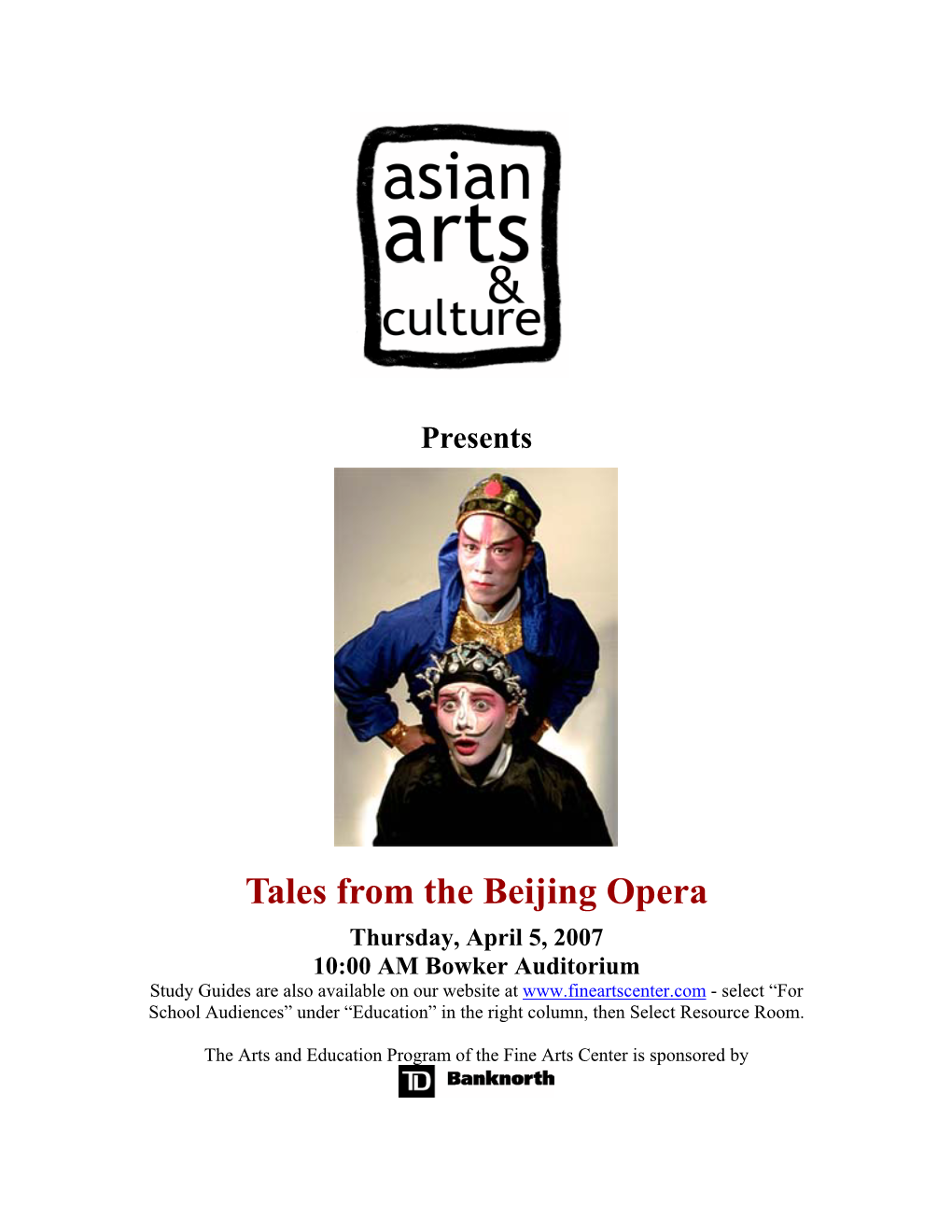

Tales from the Beijing Opera

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marco Polo 1 M. Selim Yavuz Centre for Advanced Studies in Music

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Humanities Commons Marco Polo 1 M. Selim Yavuz Centre for Advanced Studies in Music, Istanbul Technical University 05/01/2013 Symbolism and Text Painting in Tan Dun’s Marco Polo Recent opera repertoire has seen a wide variety of styles in opera composition. Marco Polo represents a rather unique corner of this wide variety. Tan Dun explores a capacious array of influences in this work. Starting from his own roots, Chinese traditional music, he explores European art tradition to some extent. Tan Dun also touches the styles and elements that are present along the journey of Marco Polo. What makes Marco Polo an interesting case study for symbolism and –to use the “old” term- madrigalism1, is the fact that this opera incorporates so many different allusions and remarks alongside with direct references. Tan Dun does not refrain from using direct references to elements outside of the European art music idiom which were/are generally left as distant allusions when used by Europe-origin composers. This might be because of the confidence brought out by the fact that he is of Chinese origin and the general opinion of European art music community that one should always embrace their own roots. This is, of course, just idle speculation. Here, the article will try to demonstrate aforementioned elements within with concrete musical examples. Tan Dun describes the departure point for composing Marco Polo as the longing to find the answer to the question that was posed to him by a Southern Chinese Monk 1 Text painting. -

Dissertation JIAN 2016 Final

The Impact of Global English in Xinjiang, China: Linguistic Capital and Identity Negotiation among the Ethnic Minority and Han Chinese Students Ge Jian A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2016 Reading Committee: Laada Bilaniuk, Chair Ann Anagnost, Chair Stevan Harrell Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Anthropology © Copyright 2016 Ge Jian University of Washington Abstract The Impact of Global English in Xinjiang, China: Linguistic Capital and Identity Negotiation among the Ethnic Minority and Han Chinese Students Ge Jian Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Professor Laada Bilaniuk Professor Ann Anagnost Department of Anthropology My dissertation is an ethnographic study of the language politics and practices of college- age English language learners in Xinjiang at the historical juncture of China’s capitalist development. In Xinjiang the international lingua franca English, the national official language Mandarin Chinese, and major Turkic languages such as Uyghur and Kazakh interact and compete for linguistic prestige in different social scenarios. The power relations between the Turkic languages, including the Uyghur language, and Mandarin Chinese is one in which minority languages are surrounded by a dominant state language supported through various institutions such as school and mass media. The much greater symbolic capital that the “legitimate language” Mandarin Chinese carries enables its native speakers to have easier access than the native Turkic speakers to jobs in the labor market. Therefore, many Uyghur parents face the dilemma of choosing between maintaining their cultural and linguistic identity and making their children more socioeconomically mobile. The entry of the global language English and the recent capitalist development in China has led to English education becoming market-oriented and commodified, which has further complicated the linguistic picture in Xinjiang. -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China Annual

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2007 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2007 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 5011 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 2007 ANNUAL REPORT VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2007 ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION OCTOBER 10, 2007 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 38–026 PDF WASHINGTON : 2007 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 01:22 Oct 11, 2007 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 38026.TXT CHINA1 PsN: CHINA1 CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate SANDER M. LEVIN, Michigan, Chairman BYRON DORGAN, North Dakota, Co-Chairman MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio MAX BAUCUS, Montana TOM UDALL, New Mexico CARL LEVIN, Michigan MICHAEL M. HONDA, California DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California TIM WALZ, Minnesota SHERROD BROWN, Ohio CHRISTOPHER H. -

The Old Master

INTRODUCTION Four main characteristics distinguish this book from other translations of Laozi. First, the base of my translation is the oldest existing edition of Laozi. It was excavated in 1973 from a tomb located in Mawangdui, the city of Changsha, Hunan Province of China, and is usually referred to as Text A of the Mawangdui Laozi because it is the older of the two texts of Laozi unearthed from it.1 Two facts prove that the text was written before 202 bce, when the first emperor of the Han dynasty began to rule over the entire China: it does not follow the naming taboo of the Han dynasty;2 its handwriting style is close to the seal script that was prevalent in the Qin dynasty (221–206 bce). Second, I have incorporated the recent archaeological discovery of Laozi-related documents, disentombed in 1993 in Jishan District’s tomb complex in the village of Guodian, near the city of Jingmen, Hubei Province of China. These documents include three bundles of bamboo slips written in the Chu script and contain passages related to the extant Laozi.3 Third, I have made extensive use of old commentaries on Laozi to provide the most comprehensive interpretations possible of each passage. Finally, I have examined myriad Chinese classic texts that are closely associated with the formation of Laozi, such as Zhuangzi, Lüshi Chunqiu (Spring and Autumn Annals of Mr. Lü), Han Feizi, and Huainanzi, to understand the intellectual and historical context of Laozi’s ideas. In addition to these characteristics, this book introduces several new interpretations of Laozi. -

7070 the E-Pang Palace

7070 The E-pang Palace E-pang Palace was built in Qin dynasty by Emperor Qin Shihuang in Xianyang, Shanxi Province. It was the largest palace ever built by human. It was so large and so magnificent that after many years of construction, it still was not completed. Building the great wall, E-pang Palace and Qin Shihuang’s tomb cost so much labor and human lives that people rose to fight against Qin Shihuang’s regime. Xiang Yu and Liu Bang were two rebel leaders at that time. Liu Bang captured Xianyang — the capital of Qin. Xiang Yu was very angry about this, and he commanded his army to march to Xianyang. Xiang Yu was the bravest and the strongest warrior at that time, and his army was much more than Liu Bang’s. So Liu Bang was frighten and retreated from Xianyang, leaving all treasures in the grand E-pang Palace untouched. When Xiang Yu took Xianyang, he burned E-pang Palce. The fire lasted for more than three months, renouncing the end of Qin dynasty. Several years later, Liu Bang defeated Xiangyu and became the first emperor of Han dynasty. He went back to E-pang Palace but saw only some pillars left. Zhang Liang and Xiao He were Liu Bang’s two most important ministers, so Liu Bang wanted to give them some awards. Liu Bang told them: “You guys can make two rectangular fences in E-pang Palace, then the land inside the fences will belongs to you. But the corners of the rectangles must be the pillars left on the ground, and two fences can’t cross or touch each other.” To simplify the problem, E-pang Palace can be consider as a plane, and pillars can be considered as points on the plane. -

Mirror, Death, and Rhetoric: Reading Later Han Chinese Bronze Artifacts Author(S): Eugene Yuejin Wang Source: the Art Bulletin, Vol

Mirror, Death, and Rhetoric: Reading Later Han Chinese Bronze Artifacts Author(s): Eugene Yuejin Wang Source: The Art Bulletin, Vol. 76, No. 3, (Sep., 1994), pp. 511-534 Published by: College Art Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3046042 Accessed: 17/04/2008 11:17 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=caa. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We enable the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. http://www.jstor.org Mirror, Death, and Rhetoric: Reading Later Han Chinese Bronze Artifacts Eugene Yuejin Wang a 1 Jian (looking/mirror), stages of development of ancient ideograph (adapted from Zhongwendazzdian [Encyclopedic dictionary of the Chinese language], Taipei, 1982, vi, 9853) History as Mirror: Trope and Artifact people. -

Banhu Playing Techniques in Northern China Yun Meng a Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of Requirements for Degree of Doct

Banhu Playing Techniques in Northern China Yun Meng A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of Requirements for degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music February 2021 Copyright of Mahasarakham University เทคนิคการบรรเลงของซอบา่ นหู ในภาคเหนือ ของประเทศจีน วิทยานิพนธ์ ของ Yun Meng เสนอต่อมหาวทิ ยาลยั มหาสารคาม เพื่อเป็นส่วนหน่ึงของการศึกษาตามหลกั สูตร ปริญญาปรัชญาดุษฎีบัณฑิต สาขาวิชาดุริยางคศิลป์ กุมภาพันธ์ 2564 ลิขสิทธ์ิเป็นของมหาวทิ ยาลยั มหาสารคาม Banhu Playing Techniques in Northern China Yun Meng A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of Requirements for Doctor of Philosophy (Music) February 2021 Copyright of Mahasarakham University The examining committee has unanimously approved this Thesis, submitted by Mr. Yun Meng , as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Music at Mahasarakham University Examining Committee Chairman (Assoc. Prof. Wiboon Trakulhun , Ph.D.) Advisor (Asst. Prof. Sayam Juangprakhon , Ph.D.) Committee (Asst. Prof. Peerapong Sensai , Ph.D.) Committee (Asst. Prof. Khomkrit Karin , Ph.D.) Committee (Assoc. Prof. Phiphat Sornyai ) Mahasarakham University has granted approval to accept this Thesis as a partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy Music (Asst. Prof. Khomkrit Karin , Ph.D.) (Assoc. Prof. Krit Chaimoon , Ph.D.) Dean of College of Music Dean of Graduate School D ABSTRACT TITLE Banhu Playing Techniques in Northern China AUTHOR Yun Meng ADVISORS Assistant Professor Sayam Juangprakhon , Ph.D. DEGREE Doctor of Philosophy MAJOR Music UNIVERSITY Mahasarakham University YEAR 2021 ABSTRACT The purpose of this thesis is to study the technique and application of Banhu. The purposes of this study are: 1) to examine the history of Banhu in northern China; 2) to classify banhu according to the difficulty of his playing skills; 3) to analyze selected music examples. -

Guo Degang: a Xiangsheng

Shenshen Cai Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne Guo Degang A Xiangsheng (Cross Talk) Performer Bridging the Gap Between Su (Vulgarity) and Ya (Elegance) Xiangsheng 相声 (cross talk), which has been one of the most popular folk art performance genres with the Chinese people since its emergence during the Qing Dynasty, began to lose its popularity at the turn of the 1990s. How- ever, this downward trajectory changed from about 2005, and it once again began to enthuse the public. The catalyst for this change in fortune has been attributed to Guo Degang and his Deyun Club 德云社. The general audience acclaim for Guo Degang’s xiangsheng performance not only turned him into a xiangsheng master and a grassroots cultural hero, it also, somewhat absurdly, evoked criticism from a few critics. The main causes of the negative critiques are the mundane themes and the ubiquitous vulgar baofu 包袱 (comical ele- ments) and rude jokes enlisted in Guo’s xiangsheng performance that revolve around the subjects of ethics, pornography, and prostitution, and which turn Guo into a signifier of vulgarity. However, with the media platform provided via the Weibo 微博 microblog, Guo Degang demonstrates his penchant for refined taste and his talent as an elegant literati. Through an in-depth analy- sis of both Guo Degang’s xiangsheng performance and his microblog entries, this paper will examine the contrasting features between Guo Degang’s artis- tic creations and his “private” life. Also, through the opposing contents and reflections of Guo Degang’s xiangsheng works and his microblog writings, an opaque and sometimes diametrically opposed insight into his worldviews is provided, and a glimpse of the dualistic nature of engagement and withdrawal from the world is revealed. -

Curriculum Vitae Bell Yung Professor of Music University of Pittsburgh (January 2011)

Bell Yung’s CV 1 Curriculum Vitae Bell Yung Professor of Music University of Pittsburgh (January 2011) Home Address 504 N. Neville St., Pittsburgh, PA 15213 Tel: (412) 681-1643 Office Address Room 206, Music Building University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA 15260 Tel: (412) 624-4061; Fax: (412) 624-4186 e-mail: [email protected] Education Ph.D. in Music, Harvard University, 1976 Ph.D. in Physics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1970 B.Sc. in Engineering Physics, University of California, Berkeley, 1964 Piano performance with Kyriana Siloti, 1967-69 Piano pedagogy at Boston University Summer School at Tanglewood, 1967 Performance studies of various instruments in the Javanese gamelan ensemble, particularly on gender barung (metal xylophone) with Pak Djokowaluya, Yogyakarta, summer 1983. Performance studies of various Chinese instruments; in particular qin (seven-string zither) with Masters Tsar Teh-yun of Hong Kong, from 1978 on, and Yao Bingyan of Shanghai, summer of 1980, 81, 82. Academic Employment University of Pittsburgh Professor of Music, 1994 (On leave 1996-98, and on leave half time 98-02) Associate Professor of Music, 1987 Assistant Professor of Music, 1981 University of Hong Kong Kwan Fong Chair in Chinese Music, University of Hong Kong, 1998.2 – 2002.7. Reader in Music, University of Hong Kong, 1996.8-1998.2 (From February 1998 to 2002, I held joint appointments at the University of Pittsburgh and the University of Hong Kong, teaching one term a year at each institution.) University of California at Davis, Visiting Associate -

Wang, Prefinal3.Indd

creators of an emperor aihe wang Creators of an Emperor: The Political Group behind the Founding of the Han Empire he enthronement of Liu Bang Ꮵ߶ initiated China’s first lasting em- T pire, the Han ዧ (206 bc–220 ad), and created a model of emperor- ship for over two millennia of subsequent dynasties. Han emperorship was a mode of Chinese authoritarianism different from the extremism of the Qin, and Liu Bang’s shadow can be recognized in many later monarchs, from Zhu Yuanzhang to Mao Zedong.1 The founding of the Han was achieved by a large group of people, addressed at the time -who sup ”,פ and in subsequent history as “Meritorious Officials ported Liu Bang in the civil war and enthroned him as the emperor. This group was, in essence, responsible for founding the Han dynasty and instituting its particular model of emperorship. To understand the formation of the Han dynasty, and more importantly, of the political culture that breeded authoritarianism, we need to understand the na- ture of this political group and its members’ divergent interests in pro- moting emperorship. Rather than focusing on the position of the group in the institu- tions of the empire, I study the participants’ own understandings and interpretations of the process of creating an emperor. My focus is not so much on the facts of events, as much as on how events were under- stood and interpreted by the participants and subsequent writers of the time. In other words, I want to bring to the analytical foreground the multitude of thoughts and words that motivated the actions and con- structed the events involved in creating an emperor, since it is through both words and deeds that we can allocate responsibility among those who created monarchy.2 To do so, I investigate three specific ques- This article was completed with the support of a research grant from the University of Hong Kong. -

A Hypothesis on the Origin of the Yu State

SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS Number 139 June, 2004 A Hypothesis on the Origin of the Yu State by Taishan Yu Victor H. Mair, Editor Sino-Platonic Papers Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA 19104-6305 USA [email protected] www.sino-platonic.org SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS FOUNDED 1986 Editor-in-Chief VICTOR H. MAIR Associate Editors PAULA ROBERTS MARK SWOFFORD ISSN 2157-9679 (print) 2157-9687 (online) SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS is an occasional series dedicated to making available to specialists and the interested public the results of research that, because of its unconventional or controversial nature, might otherwise go unpublished. The editor-in-chief actively encourages younger, not yet well established, scholars and independent authors to submit manuscripts for consideration. Contributions in any of the major scholarly languages of the world, including romanized modern standard Mandarin (MSM) and Japanese, are acceptable. In special circumstances, papers written in one of the Sinitic topolects (fangyan) may be considered for publication. Although the chief focus of Sino-Platonic Papers is on the intercultural relations of China with other peoples, challenging and creative studies on a wide variety of philological subjects will be entertained. This series is not the place for safe, sober, and stodgy presentations. Sino- Platonic Papers prefers lively work that, while taking reasonable risks to advance the field, capitalizes on brilliant new insights into the development of civilization. Submissions are regularly sent out to be refereed, and extensive editorial suggestions for revision may be offered. Sino-Platonic Papers emphasizes substance over form. We do, however, strongly recommend that prospective authors consult our style guidelines at www.sino-platonic.org/stylesheet.doc. -

Please Click Here to Download

No.1 October 2019 EDITORS-IN-CHIEF Tobias BIANCONE, GONG Baorong EDITORIAL BOARD MEMBERS (in alphabetical order by Pinyin of last name) Tobias BIANCONE, Georges BANU, Christian BIET, Marvin CARLSON, CHEN Jun, CHEN Shixiong, DING Luonan, Erika FISCHER-LICHTE, FU Qiumin, GONG Baorong, HE Chengzhou, HUANG Changyong, Hans-Georg KNOPP, HU Zhiyi, LI Ruru, LI Wei, LIU Qing, LIU Siyuan, Patrice PAVIS, Richard SCHECHNER, SHEN Lin, Kalina STEFANOVA, SUN Huizhu, WANG Yun, XIE Wei, YANG Yang, YE Changhai, YU Jianchun. EDITORS WU Aili, CHEN Zhongwen, CHEN Ying, CAI Yan CHINESE TO ENGLISH TRANSLATORS HE Xuehan, LAN Xiaolan, TANG Jia, TANG Yuanmei, YAN Puxi ENGLISH CORRECTORS LIANG Chaoqun, HUANG Guoqi, TONG Rongtian, XIONG Lingling,LIAN Youping PROOFREADERS ZHANG Qing, GUI Han DESIGNER SHAO Min CONTACT TA The Center Of International Theater Studies-S CAI Yan: [email protected] CHEN Ying: [email protected] CONTENTS I 1 No.1 CONTENTS October 2019 PREFACE 2 Empowering and Promoting Chinese Performing Arts Culture / TOBIAS BIANCONE 4 Let’s Bridge the Culture Divide with Theatre / GONG BAORONG STUDIES ON MEI LANFANG 8 On the Subjectivity of Theoretical Construction of Xiqu— Starting from Doubt on “Mei Lanfang’s Performing System” / CHEN SHIXIONG 18 The Worldwide Significance of Mei Lanfang’s Performing Art / ZOU YUANJIANG 31 Mei Lanfang, Cheng Yanqiu, Qi Rushan and Early Xiqu Directors / FU QIUMIN 46 Return to Silence at the Golden Age—Discussion on the Gains and Losses of Mei Lanfang’s Red Chamber / WANG YONGEN HISTORY AND ARTISTS OF XIQU 61 The Formation