Moderate the MAOA-L Allele Expression with CRISPR/Cas9 System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genes in Eyecare Geneseyedoc 3 W.M

Genes in Eyecare geneseyedoc 3 W.M. Lyle and T.D. Williams 15 Mar 04 This information has been gathered from several sources; however, the principal source is V. A. McKusick’s Mendelian Inheritance in Man on CD-ROM. Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998. Other sources include McKusick’s, Mendelian Inheritance in Man. Catalogs of Human Genes and Genetic Disorders. Baltimore. Johns Hopkins University Press 1998 (12th edition). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Omim See also S.P.Daiger, L.S. Sullivan, and B.J.F. Rossiter Ret Net http://www.sph.uth.tmc.edu/Retnet disease.htm/. Also E.I. Traboulsi’s, Genetic Diseases of the Eye, New York, Oxford University Press, 1998. And Genetics in Primary Eyecare and Clinical Medicine by M.R. Seashore and R.S.Wappner, Appleton and Lange 1996. M. Ridley’s book Genome published in 2000 by Perennial provides additional information. Ridley estimates that we have 60,000 to 80,000 genes. See also R.M. Henig’s book The Monk in the Garden: The Lost and Found Genius of Gregor Mendel, published by Houghton Mifflin in 2001 which tells about the Father of Genetics. The 3rd edition of F. H. Roy’s book Ocular Syndromes and Systemic Diseases published by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins in 2002 facilitates differential diagnosis. Additional information is provided in D. Pavan-Langston’s Manual of Ocular Diagnosis and Therapy (5th edition) published by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins in 2002. M.A. Foote wrote Basic Human Genetics for Medical Writers in the AMWA Journal 2002;17:7-17. A compilation such as this might suggest that one gene = one disease. -

Whole Exome Sequencing Gene Package Intellectual Disability, Version 9.1, 31-1-2020

Whole Exome Sequencing Gene package Intellectual disability, version 9.1, 31-1-2020 Technical information DNA was enriched using Agilent SureSelect DNA + SureSelect OneSeq 300kb CNV Backbone + Human All Exon V7 capture and paired-end sequenced on the Illumina platform (outsourced). The aim is to obtain 10 Giga base pairs per exome with a mapped fraction of 0.99. The average coverage of the exome is ~50x. Duplicate and non-unique reads are excluded. Data are demultiplexed with bcl2fastq Conversion Software from Illumina. Reads are mapped to the genome using the BWA-MEM algorithm (reference: http://bio-bwa.sourceforge.net/). Variant detection is performed by the Genome Analysis Toolkit HaplotypeCaller (reference: http://www.broadinstitute.org/gatk/). The detected variants are filtered and annotated with Cartagenia software and classified with Alamut Visual. It is not excluded that pathogenic mutations are being missed using this technology. At this moment, there is not enough information about the sensitivity of this technique with respect to the detection of deletions and duplications of more than 5 nucleotides and of somatic mosaic mutations (all types of sequence changes). HGNC approved Phenotype description including OMIM phenotype ID(s) OMIM median depth % covered % covered % covered gene symbol gene ID >10x >20x >30x A2ML1 {Otitis media, susceptibility to}, 166760 610627 66 100 100 96 AARS1 Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, axonal, type 2N, 613287 601065 63 100 97 90 Epileptic encephalopathy, early infantile, 29, 616339 AASS Hyperlysinemia, -

Test Catalogue August 2019

Test Catalogue August 2019 www.centogene.com/catalogue Table of Contents CENTOGENE CLINICAL DIAGNOSTIC PRODUCTS AND SERVICES › Whole Exome Testing 4 › Whole Genome Testing 5 › Genome wide CNV Analysis 5 › Somatic Mutation Analyses 5 › Biomarker Testing, Biochemical Testing 6 › Prenatal Testing 7 › Additional Services 7 › Metabolic Diseases 9 - 21 › Neurological Diseases 23 - 47 › Ophthalmological Diseases 49 - 55 › Ear, Nose and Throat Diseases 57 - 61 › Bone, Skin and Immune Diseases 63 - 73 › Cardiological Diseases 75 - 79 › Vascular Diseases 81 - 82 › Liver, Kidney and Endocrinological Diseases 83 - 89 › Reproductive Genetics 91 › Haematological Diseases 93 - 96 › Malformation and/or Retardation Syndromes 97 - 107 › Oncogenetics 109 - 113 ® › CentoXome - Sequencing targeting exonic regions of ~20.000 genes Test Test name Description code CentoXome® Solo Medical interpretation/report of WES findings for index 50029 CentoXome® Solo - Variants Raw data; fastQ, BAM, Vcf files along with variant annotated file in xls format for index 50028 CentoXome® Solo - with CNV Medical interpretation/report of WES including CNV findings for index 50103 Medical interpretation/report of WES in index, package including genome wide analyses of structural/ CentoXome® Solo - with sWGS 50104 large CNVs through sWGS Medical interpretation/report of WES in index, package including genome wide analyses of structural/ CentoXome® Solo - with aCGH 750k 50122 large CNVs through 750k microarray Medical interpretation/report of WES in index, package including genome -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2016/0281166 A1 BHATTACHARJEE Et Al

US 20160281 166A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2016/0281166 A1 BHATTACHARJEE et al. (43) Pub. Date: Sep. 29, 2016 (54) METHODS AND SYSTEMIS FOR SCREENING Publication Classification DISEASES IN SUBJECTS (51) Int. Cl. (71) Applicant: PARABASE GENOMICS, INC., CI2O I/68 (2006.01) Boston, MA (US) C40B 30/02 (2006.01) (72) Inventors: Arindam BHATTACHARJEE, G06F 9/22 (2006.01) Andover, MA (US); Tanya (52) U.S. Cl. SOKOLSKY, Cambridge, MA (US); CPC ............. CI2O 1/6883 (2013.01); G06F 19/22 Edwin NAYLOR, Mt. Pleasant, SC (2013.01); C40B 30/02 (2013.01); C12O (US); Richard B. PARAD, Newton, 2600/156 (2013.01); C12O 2600/158 MA (US); Evan MAUCELI, (2013.01) Roslindale, MA (US) (21) Appl. No.: 15/078,579 (57) ABSTRACT (22) Filed: Mar. 23, 2016 Related U.S. Application Data The present disclosure provides systems, devices, and meth (60) Provisional application No. 62/136,836, filed on Mar. ods for a fast-turnaround, minimally invasive, and/or cost 23, 2015, provisional application No. 62/137,745, effective assay for Screening diseases, such as genetic dis filed on Mar. 24, 2015. orders and/or pathogens, in Subjects. Patent Application Publication Sep. 29, 2016 Sheet 1 of 23 US 2016/0281166 A1 SSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSSS S{}}\\93? sau36 Patent Application Publication Sep. 29, 2016 Sheet 2 of 23 US 2016/0281166 A1 &**** ? ???zzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzz??º & %&&zzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzzz &Sssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssssss & s s sS ------------------------------ Patent Application Publication Sep. 29, 2016 Sheet 3 of 23 US 2016/0281166 A1 23 25 20 FG, 2. Patent Application Publication Sep. 29, 2016 Sheet 4 of 23 US 2016/0281166 A1 : S Patent Application Publication Sep. -

Prenatalscreen® Standard Technical Report

About PrenatalScreen® Prenatal Test PrenatalScreen® Prenatal Test is a genetic test that analyses fetal DNA, obtained from CVS or amniotic fluid following an invasive prenatal diagnosis, to screen for monogenic disorders in the fetus. Using the latest technologies, including Next Generation Sequencing (NGS), PrenatalScreen® Prenatal Test screen 744 genes for mutations causing over 1.000 severe genetic disorders in the fetus. PrenatalScreen® Prenatal Test allows for a comprehensive care and enables patients to make more informed reproductive decisions. Offering PrenatalScreen® Prenatal Test to a patient during pregnancy allows her to gain more knowledge about the potential to pass along a condition to the fetus. Aim of the test PrenatalScreen® Prenatal Test analyses DNA extracted from fetal cells in the amniotic fluid, collected through amniocentesis, or in the chorionic villi through villocentesis (CVS). The aim of this diagnositc test is to assess severe genetic diseases in the fetus, including the most common diseases in the European population. Genes listed in Table 1 were selected according to the incidence in the population of the disease caused by mutations in such genes, the severity of the clinical phenotype at birth and the importance of the related pathogenetic picture, in accordance with the indications of the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG)(Grody et al., Genet Med 2013:15:482–483). PrenatalScreen®: Indication for testing PrenatalScreen® Prenatal Test is intended for patients who meet any of the following criteria: • Personal/familial anamnesis of hereditary genetic diseases; • For expectant mothers wishing to reduce the risk of a genetic diseases in the fetus; • For natural or in vitro fertilization (IVF)-derived pregnancies: • For couples using heterologus IVF procedures (egg/sperm donors). -

Supplementary Information Novel Findings from Family-Based Exome

Supplementary Information Novel findings from family-based exome sequencing for children with biliary atresia Kien Trung Tran1*, Vinh Sy Le1,2*, Lan Thi Mai Dao1, Huyen Khanh Nguyen3, Anh Kieu Mai4, Ha Thi Nguyen4, Minh Duy Ngo4, Quynh Anh Tran5, Liem Thanh Nguyen1 1Vinmec Research Institute of Stem Cell and Gene Technology, 458 Minh Khai, Hai Ba Trung district, Hanoi, Vietnam. 2 University of Engineering and Technology, Vietnam National University Hanoi, 144 Xuan Thuy, Cau Giay district, Hanoi, Vietnam. 3 Bioequivalence Center, National Institute of Drug Quality Control, 11/157 Bang B, Hoang Mai district, Hanoi, Vietnam. 4Vinmec International Hospital, 458 Minh Khai, Hai Ba Trung district, Hanoi, Vietnam. 5Vietnam National Children’s Hospital, 18/879 La Thanh, Dong Da district, Hanoi, Vietnam. Correspondence: Kien Trung Tran, email: [email protected]; Liem Thanh Nguyen, email: [email protected] 1 Table S1. Prediction of structural changes I-mutant Gene A.A change Stability DDG (kcal/mol) HACE1 p.Ala651Thr Decrease -1.15 PHKA1 p.Asp160Asn Decrease -1.71 THOC2 p.Ala421Thr Decrease -1.28 XIAP p.Ala321Gly Decrease -0.3 VPS13C p.Ala2043Gly Decrease -1.71 AMER1 p.Ser359Cys Decrease -1.6 ATRX p.Pro2478Ala Decrease 0.52 POF1B p.Ser109Arg Decrease -0.73 BCORL1 p.Arg890Gln Decrease -0.68 INVS p.Arg396* N/A BCOR p.Pro483Leu Decrease -1.36 UBQLN2 p.Pro478Ala Decrease -1.73 MAOA p.V70M Decrease -2.58 IRS4 p.Trp945Cys Decrease -0.93 ELP2 p.Ala445Val Decrease -1.1 RAPGEF4 p.Gln622Lys Decrease -0.35 OCRL p.Met876Lys Increase 0.48 TINAG p.Ala76Val Decrease -0.27 CEP63 p.Gln490Lys Decrease -0.45 CCDC136 p.Ala862Glu Decrease -0.75 BCAR1 p.Ala10Val Decrease 0.48 FOCAD p.Pro1269Thr Decrease -1.33 KIF4A p.Asn392His Decrease -1.76 ZNF41 p.Arg299Cys Decrease -1.08 ARSF p.Pro504Leu Decrease -1.39 AMER1 p.Thr708Asn Decrease -0.77 INVS p.Leu40Val Decrease -1.58 OCRL p.Asp89His Decrease -1.94 A.A: amino acid; DDG: free energy change; N/A: not available. -

Contiguous Gene Deletion of Chromosome Xp in Three Families

Case Report iMedPub Journals Journal of Rare Disorders: Diagnosis & Therapy 2015 http://wwwimedpub.com ISSN 2380-7245 Vol. 1 No. 1:3 DOI: 10.21767/2380-7245.100003 Contiguous Gene Deletion of Shailly Jain-Ghai1,5, Stephanie Skinner1, Chromosome Xp in Three Families Jessica Hartley2,3, Encompassing OTC, RPGR and Stephanie Fox4, TSPAN7 Genes Daniela Buhas4, Cheryl Rockman- Greenberg2,3 and Alicia Chan1,5 Abstract Ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency (OTCD) is the most common urea cycle 1 Medical Genetics Clinic, Stollery disorder. The classic presentation in males is hyperammonemic encephalopathy Children's Hospital, Edmonton, Alberta, in the early neonatal period. Given the X-linked inheritance of OTCD, presentation Canada in females is highly variable. We present three families with different contiguous 2 Program in Genetics and Metabolism, Winnipeg Regional Health Authority gene deletions on chromosome Xp. Deletion ofRPGR , OTC and TSPAN7 is common and University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, to all three families in our series. These cases highlight the variable phenotype Manitoba, Canada in manifesting OTCD female carriers, the complexity of OTCD management and 3 Department of Biochemistry and complex issues surrounding the option of liver transplantation when multiple Medical Genetics, University of other genetic factors play a role. Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada 4 Department of Medical Genetics, Keywords: Ornithine transcarbamylase; Ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency; Montreal Children’s Hospital, McGill Contiguous gene deletion; -

Gen- Symbol Genname Erkrankung(En) OMIM Gengröße

Gen‐ Gengröße Genname Erkrankung(en) OMIM symbol (kb) Arterial calcification, generalized, of infancy, 2 614473 ABCC6 ATP‐BINDING CASSETTE, SUBFAMILY C, MEMBER 6 Pseudoxanthoma elasticum 264800 4,5 Pseudoxanthoma elasticum, forme fruste 177850 ACSL4 ACYL‐CoA SYNTHETASE LONG CHAIN FAMILY, MEMBER 4 Mental retardation, X‐linked 63 300387 2,1 AFF2 AF4/FMR2 FAMILY, MEMBER 2 (FMR2) Mental retardation, X‐linked, FRAXE type 309548 3,9 APOPTOSIS‐INDUCING FACTOR, MITOCHONDRION‐ASSOCIATED, 1 Combined oxidative phosphorylation deficiency 6 300816 AIFM1 1,8 (PDCD8) Cowchock syndrome 310490 Proteus syndrome, somatic 176920 AKT1 V‐AKT MURINE THYMOMA VIRAL ONCOGENE HOMOLOG 1 1,4 Cowden syndrome 6 615109 Megalencephaly‐polymicrogyria‐polydactyly‐hydrocephalus AKT3 V‐AKT MURINE THYMOMA VIRAL ONCOGENE HOMOLOG 3 (PKBG) 615937 1,4 syndrome 2 AP1S2 ADAPTOR‐RELATED PROTEIN COMPLEX 1, SIGMA‐2 SUBUNIT Mental retardation, X‐linked syndromic 5 304340 0,5 ARHGEF6 RHO GUANINE NUCLEOTIDE EXCHANGE FACTOR 6 (PIXA) Mental retardation, X‐linked 46 300436 2,3 ARHGEF9 RHO GUANINE NUCLEOTIDE EXCHANGE FACTOR 9 (PEM2) Epileptic encephalopathy, early infantile, 8 300607 1,6 ARID1A AT‐RICH INTERACTION DOMAIN‐CONTAINING PROTEIN 1A (SMARCF1) Coffin‐Siris syndrome 2 614607 6,9 ARID1B AT‐RICH INTERACTION DOMAIN‐CONTAINING PROTEIN 1B Coffin‐Siris syndrome 1 135900 6,7 Epileptic encephalopathy, early infantile, 1 308350 Hydranencephaly with abnormal genitalia 300215 Lissencephaly, X‐linked 2 300215 ARX ARISTALESS‐RELATED HOMEOBOX, X‐LINKED 1,7 Mental retardation, X‐linked 29 and others -

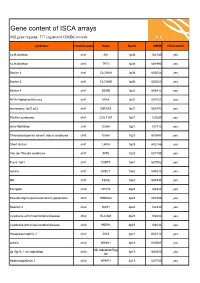

ISCA Disease List

Gene content of ISCA arrays 402 gene regions, 377 registered OMIM records syndrome chromosome Gene Band OMIM ISCA 8x60k 1p36 deletion chr1 SKI 1p36 164780 yes 1p36 deletion chr1 TP73 1p36 601990 yes Bartter 4 chr1 CLCNKA 1p36 602024 yes Bartter 3 chr1 CLCNKB 1p36 602023 yes Bartter 4 chr1 BSND 1p32 606412 yes NFIA Haploinsufficiency chr1 NFIA 1p31 600727 yes monosomy 1p31 p22 chr1 DIRAS3 1p31 605193 yes Stickler syndrome chr1 COL11A1 1p21 120280 yes atrial fibrillation chr1 GJA5 1q21 121013 yes Thrombocytopenia absent radius syndrome chr1 GJA8 1q21 600897 yes Short stature chr1 LHX4 1q25 602146 yes Van der Woude syndrome chr1 IRF6 1q32 607199 yes Fryns 1q41 chr1 DISP1 1q41 607502 yes autism chr1 DISC1 1q42 605210 yes MR chr1 TBCE 1q42 604934 yes Feingold chr2 MYCN 2q24 164840 yes Pseudovaginal perineoscrotal hypospadias chr2 SRD5A2 2p23 607306 yes Noonan 4 chr2 SOS1 2p22 182530 yes Cystinuria with mitochondrial disease chr2 SLC3A1 2p21 104614 yes Cystinuria with mitochondrial disease chr2 PREPL 2p21 104614 yes Holopresencaphly 2 chr2 SIX3 2p21 603714 yes autism chr2 NRXN1 2p16 600565 yes MicrodeletionReg 2p15p16.1 microdeletion chr2 2p15 602559 yes ion Nephronophthsis 1 chr2 NPHP1 2q13 607100 yes Holoprosencephaly 9 chr2 GLI2 2q14 165230 yes visceral heterotaxy chr2 CFC1 2q21 605194 yes Mowat-Wilson syndrome chr2 ZEB2 2q22 605802 yes autism chr2 SLC4A10 2q24 605556 yes SCN1A-related seizures chr2 SCN1A 2q24 182389 yes HYPOMYELINATION, GLOBAL CEREBRAL chr2 SLC25A12 2q31 603667 yes Split/hand foot malformation -5 chr2 DLX1 2q31 600029 yes -

Download CGT Exome V2.0

CGT Exome version 2. -

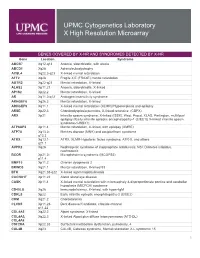

Genes Covered and Disorders Detected by X-HR Microarray

UPMC Cytogenetics Laboratory X High Resolution Microarray GENES COVERED BY X-HR AND SYNDROMES DETECTED BY X-HR Gene Location Syndrome ABCB7 Xq12-q13 Anemia, sideroblastic, with ataxia ABCD1 Xq28 Adrenoleukodystrophy ACSL4 Xq22.3-q23 X-linked mental retardation AFF2 Xq28 Fragile X E (FRAXE) mental retardation AGTR2 Xq22-q23 Mental retardation, X-linked ALAS2 Xp11.21 Anemia, sideroblastic, X-linked AP1S2 Xp22.2 Mental retardation, X-linked AR Xq11.2-q12 Androgen insensitivity syndrome ARHGEF6 Xq26.3 Mental retardation, X-linked ARHGEF9 Xq11.1 X-linked mental retardation (XLMR)//Hyperekplexia and epilepsy ARSE Xp22.3 Chondrodysplasia punctata, X-linked recessive (CDPX) ARX Xp21 Infantile spasm syndrome, X-linked (ISSX), West, Proud, XLAG, Partington, multifocal epilepsy //Early infantile epileptic encephalopathy-1 (EIEE1)( X-linked infantile spasm syndrome-1-ISSX1) ATP6AP2 Xp11.4 Mental retardation, X-linked, with epilepsy (XMRE) ATP7A Xq13.2- Menkes disease (MNK) and occipital horn syndrome q13.3 ATRX Xq13.1- ATRX, XLMR-Hypotonic facies syndrome, ATR-X, and others q21.1 AVPR2 Xq28 Nephrogenic syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis; NSI; Diabetes insipidus, nephrogenic BCOR Xp21.2- Microphthalmia syndromic (MCOPS2) p11.4 BMP15 Xp11.2 Ovarian dysgenesis 2 BRWD3 Xq21.1 Mental retardation, X-linked 93 BTK Xq21.33-q22 X-linked agammaglobulinemia CACNA1F Xp11.23 Aland Island eye disease CASK Xp11.4 X-linked mental retardation with microcephaly & disproportionate pontine and cerebellar hypoplasia (MICPCH) syndrome CD40LG Xq26 Immunodeficiency, -

Genetic Architecture for Human Aggression: a Study of Gene–Phenotype Relationship in OMIM Yanli Zhang-James1 and Stephen V

RESEARCH ARTICLE Neuropsychiatric Genetics Genetic Architecture for Human Aggression: A Study of Gene–Phenotype Relationship in OMIM Yanli Zhang-James1 and Stephen V. Faraone1,2,3* 1Department of Psychiatry, SUNY Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, New York 2Department of Neuroscience and Physiology, SUNY Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, New York 3K.G. Jebsen Centre for Research on Neuropsychiatric Disorders, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway Manuscript Received: 22 June 2015; Manuscript Accepted: 5 August 2015 Genetic studies of human aggression have mainly focused on known candidate genes and pathways regulating serotonin and How to Cite this Article: dopamine signaling and hormonal functions. These studies have Zhang-James Y, Faraone SV. 2016. Genetic taught us much about the genetics of human aggression, but no Architecture for Human Aggression: A genetic locus has yet achieved genome-significance. We here Study of Gene–Phenotype Relationship in present a review based on a paradoxical hypothesis that studies OMIM. of rare, functional genetic variations can lead to a better under- Am J Med Genet Part B 171B:641–649. standing of the molecular mechanisms underlying complex multifactorial disorders such as aggression. We examined all aggression phenotypes catalogued in Online Mendelian Inheri- tance in Man (OMIM), an Online Catalog of Human Genes and 2014]. Thus, identifying causal genes and pathways underlying Genetic Disorders. We identified 95 human disorders that have aggressive behavior in humans requires additional work. documented aggressive symptoms in at least one individual with The lack of significant associations for common variants is likely a well-defined genetic variant. Altogether, we retrieved 86 causal due to many reasons such as sample heterogeneity, variants of small genes.