Abjection in Late Nineteenth Century British Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

From Prodigy to Pathology: "Monstrosity" in the British Novel from 1850 to 1930

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2013 From Prodigy to Pathology: "Monstrosity" in the British Novel from 1850 to 1930 Terri Beth Miller University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Terri Beth, "From Prodigy to Pathology: "Monstrosity" in the British Novel from 1850 to 1930. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2013. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/2462 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Terri Beth Miller entitled "From Prodigy to Pathology: "Monstrosity" in the British Novel from 1850 to 1930." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in English. Urmila Seshagiri, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Stanton B. Garner Jr., Amy Elias, Bryant Creel Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) From Prodigy to Pathology: “Monstrosity” in the British Novel from 1850 to 1930 A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Terri Beth Miller August 2013 Copyright 2013 by Terri Beth Miller. -

Exile for Dreamers - Tess’S Story Kathleen Baldwin Baldwin, Page 1

Exile for Dreamers - Tess’s Story Kathleen Baldwin Baldwin, page 1 Exile for Dreamers —A Stranje House Novel— By Kathleen Baldwin Exile for Dreamers - Tess’s Story Kathleen Baldwin Baldwin, page 2 Dedication To the men who taught me to run, swim, hunt, gallop horses, ride the rapids, ski powder, hang-glide, and rock climb - back when girls did not do that sort of thing. To Daddy, for teaching me to box at a time when it was sacrilegious to strap a pair of boxing gloves on a little girl, and to the boys whose noses I broke – I am truly sorry. And to Susan Thank you for your extraordinary skills as an editor. I’m grateful you can see when I am blind. Exile for Dreamers - Tess’s Story Kathleen Baldwin Baldwin, page 3 Chapter 1 Tess I run to escape my dreams. Dreams are my curse. Every night they haunt me, every morning I outrun them, and every evening they catch me again. One day they will devour my soul. But not today. Not this hour. I ran with Phobos and Trobos, the half wolves half dogs who guard Stranje House. We raced into the cleansing wind. What is the pace of forgetfulness? How fast must one go? “Tess! Wait!” Georgiana’s gasps cut through the peace of the predawn air and broke my rhythm. I slowed to a stop and turned. A moment later, Phobos broke stride too, and trotted back beside me. He issued a low almost imperceptible growl, impatient to return to our race. Georgie leaned forward breathing hard. -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

Genesys John Peel 78339 221 2 2 Timewyrm: Exodus Terrance Dicks

Sheet1 No. Title Author Words Pages 1 1 Timewyrm: Genesys John Peel 78,339 221 2 2 Timewyrm: Exodus Terrance Dicks 65,011 183 3 3 Timewyrm: Apocalypse Nigel Robinson 54,112 152 4 4 Timewyrm: Revelation Paul Cornell 72,183 203 5 5 Cat's Cradle: Time's Crucible Marc Platt 90,219 254 6 6 Cat's Cradle: Warhead Andrew Cartmel 93,593 264 7 7 Cat's Cradle: Witch Mark Andrew Hunt 90,112 254 8 8 Nightshade Mark Gatiss 74,171 209 9 9 Love and War Paul Cornell 79,394 224 10 10 Transit Ben Aaronovitch 87,742 247 11 11 The Highest Science Gareth Roberts 82,963 234 12 12 The Pit Neil Penswick 79,502 224 13 13 Deceit Peter Darvill-Evans 97,873 276 14 14 Lucifer Rising Jim Mortimore and Andy Lane 95,067 268 15 15 White Darkness David A McIntee 76,731 216 16 16 Shadowmind Christopher Bulis 83,986 237 17 17 Birthright Nigel Robinson 59,857 169 18 18 Iceberg David Banks 81,917 231 19 19 Blood Heat Jim Mortimore 95,248 268 20 20 The Dimension Riders Daniel Blythe 72,411 204 21 21 The Left-Handed Hummingbird Kate Orman 78,964 222 22 22 Conundrum Steve Lyons 81,074 228 23 23 No Future Paul Cornell 82,862 233 24 24 Tragedy Day Gareth Roberts 89,322 252 25 25 Legacy Gary Russell 92,770 261 26 26 Theatre of War Justin Richards 95,644 269 27 27 All-Consuming Fire Andy Lane 91,827 259 28 28 Blood Harvest Terrance Dicks 84,660 238 29 29 Strange England Simon Messingham 87,007 245 30 30 First Frontier David A McIntee 89,802 253 31 31 St Anthony's Fire Mark Gatiss 77,709 219 32 32 Falls the Shadow Daniel O'Mahony 109,402 308 33 33 Parasite Jim Mortimore 95,844 270 -

Why Popular Culture Matters

THE POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL MIDWEST PCA/ACA VOLUME 7 | NUMBER 1 | 2019 WHY POPULAR CULTURE MATTERS EDITED BY: CARRIELYnn D. REINHARD POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL VOLUME 7 NUMBER 1 2019 Editor CARRIELYNN D. REINHARD Dominican University Managing Editor JULIA LARGENT McPherson College Assistant Editor GARRET L. CASTLEBERRY Mid-America Christian University Copy Editor KEVIN CALCAMP Queens University of Charlotte Reviews Editor MALYNNDA JOHNSON Indiana State University Assistant Reviews Editor CHRISTOPHER J. OLSON University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Graphics Editor ETHAN CHITTY Purdue University Please visit the PCSJ at: http://mpcaaca.org/the-popular- culture-studies-journal. Popular Culture Studies Journal is the official journal of the Midwest Popular and American Culture Association. Copyright © 2019 Midwest Popular and American Culture Association. All rights reserved. MPCA/ACA, 421 W. Huron St Unit 1304, Chicago, IL 60654 EDITORIAL BOARD CORTNEY BARKO PAUL BOOTH West Virginia University DePaul University KATIE WILSON ANTHONY ADAH University of Louisville Minnesota State University, Moorhead GARY BURNS BRIAN COGAN Northern Illinois University Molloy College ART HERBIG ANDREW F. HERRMANN Indiana University - Purdue University, Fort Wayne East Tennessee State University CARLOS D. MORRISON KIT MEDJESKY Alabama State University University of Findlay SALVADOR MURGUIA ANGELA NELSON Akita International University Bowling Green State University CARYN NEUMANN ALLISON R. LEVIN Miami University Webster University JENNIFER FARRELL Milwaukee School of Engineering ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction: Why Popular Culture Matters ........................ 1 CARRIELYNN D. REINHARD Special Entry: Multimedia Presentation of “Why Popular Culture Matters” ............................................ 4 CARRIELYNN D. REINHARD Editorial: I’m So Bored with the Canon: Removing the Qualifier “Popular” from Our Cultures .......................... 6 SCOTT M. -

Robert Donat, Film Acting and the 39 Steps (1935) Victoria Lowe, University of Manchester, UK

'Performing Hitchcock': Robert Donat, Film Acting and The 39 Steps (1935) Victoria Lowe, University of Manchester, UK This article offers a speculative exploration of performance in a Hitchcock film by looking in detail at Robert Donat's characterisation of Richard Hannay in The 39 Steps (1935). It has been argued that Hitchcock's preference for the actor who can do nothing well leads to a de- emphasising of the acting skill of his cast whilst foregrounding the technical elements such as editing and mise-en-scène in the construction of emotional effects (Ryall, 1996:159). Hitchcock's own attitude to actors is thought to be indicated by his oft-quoted claim that "actors should be treated like cattle." [1] However, this image of Hitchcock as a director unconcerned with the work of his actors seems to be contradicted both by the range of thoughtful and complex performances to be found in his films and by the testimonies of the actors themselves with regard to working with him. [2] In this article therefore, I will attempt to unpick some of the issues regarding performance in Hitchcock films through a detailed case study of Robert Donat and his performance in The 39 Steps. Initially, I will look at the development of Donat's star persona in the early 1930s and how during the making of The 39 Steps, writing about Donat in the press began to articulate performance as opposed to star discourses. I will then look at some of Donat's published and unpublished writing to determine the screen acting methodologies he was beginning to develop at the time. -

SL English First Semester

1 111 PANORAMA (PART ONE) Additional English (S.L) Textbook prescribed by SRTM University, Nanded as per CBCS pattern Members of Board of Studies in English, SRTM University, Nanded Dr Mahesh M Nivargi Associate Professor, Department of English, (Chairman) Mahatma Gandhi Mahavidyalaya, Ahmedpur, Dist. Latur – 413515 Dr Ajay R Tengse Associate Professor and Head, Department of English, Yeshwant Mahavidyalaya, Nanded – 431602 Dr Rajaram C Jadhav Head, Department of English, Shivaji Mahavidyalaya, Renapur, Dist. Latur – 413527 Dr Arvind M Nawale Head, Department of English, Shivaji Mahavidyalaya, Udgir, Dist. Latur – 413517 Dr Dilip V Chavan Professor and Head, Department of English, School of Language, Literature and Culture Studies, SRTM University, Nanded – 431606 Dr Shailaja B Wadikar Associate Professor, Department of English, School of Language, Literature and Culture Studies, SRTM University, Nanded – 431606 Dr Atmaram S Gangane Associate Professor and Head, Department of English, DSM‘s College of Arts, Commerce and Science, Parbhani – 431401 Dr Manisha B Gahelot Associate Professor, Department of English, People‘s College, Nanded – 431602 Dr Prashant M Mannikar Associate Professor and Head, Department of English, Dayanand College of Arts, Latur – 413512 Dr Kishor N Ingole Assistant Professor, Department of English, Shivaji College, Hingoli – 431513 Dr Uttam B Ambhore Professor, Department of English, Dr BAM University, Aurangabad - 431004 Dr Muktja V Mathakari Principal SNDT College of Home Sciences, Pune – 411 004 Dr Manish S Wankhede Associate Professor, Department of English, Dhanwate National College, Nagpur – 440 027 Mr Sudarshan Kecheri Managing Director, Authorspress, Q-2A, HauzKhas Enclave, New Delhi – 110 016 Dr Sandhya Tiwari, Director, CELT, Palamuru University, Mahbubnagar – 509 001 PANORAMA (Part - I) Additional English (S.L) A Textbook for U.G. -

E Choices We Make

August / Septem ber 2 012 e Choices We Make Where We Belong more to them than friendship. OCTAVIA BOOKS The tension and intensity are Marian Caldwell is a thirty-six 513 Octavia Street palpable, as we examine the year old television producer, New Orleans, LA 70115 values that lie at the heart of our living her dream in New York 504-899-READ (7323) most intimate relationships, and City. With a fulfi lling career and octaviabooks.com the choices we make when lives satisfying relationship, she has [email protected] are at stake and everything is on convinced everyone, including the line. STORE HOURS herself, that her life is just as she wants it to be. But one Open 10 am - 6 pm The Sandcastle Girls Monday - Saturday night, Marian answers a knock on the door . only to fi nd Sunday 12 Noon - 5 pm Kirby Rose, an eighteen-year-old girl with a key to a past Through fourteen previous best-selling stories, like that Marian thought she had sealed off forever. From the Midwives and Skeletons at the Feast, Chris Bohjalian moment Kirby appears on her doorstep, Marian’s perfectly has taken us on a vast array of journeys. His latest, The constructed world--and her very identity--will be shaken to Sandcastle Girls ($25.95, Doubleday, 978-0-385-53479-6), its core, resurrecting ghosts and memories of a passionate is a sweeping historical love story steeped in the author’s young love affair that threaten everything that has come to Armenian heritage, making it his most personal novel to defi ne her. -

Little Father Time in Jude the Obscure

Colby Quarterly Volume 23 Issue 1 March Article 6 March 1987 A Shadow from the Past: Little Father Time in Jude the Obscure Suzanne Edwards Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cq Recommended Citation Colby Library Quarterly, Volume 23, no.1, March 1987, p.32-38 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Colby. It has been accepted for inclusion in Colby Quarterly by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Colby. Edwards: A Shadow from the Past: Little Father Time in Jude the Obscure A Shadow from the Past: Little Father Time in Jude the Obscure by SUZANNE EDWARDS TITTLE FATHER TIME, the morbidly self-conscious child in Thomas L Hardy's Jude the Obscure who hangs himself and his younger brother and sister, has provoked considerable critical commentary over the years. He has been variously interpreted as a grotesque monster, a Christ figure, a prophet of Doom, the choric voice of History, and a sym bol of the Modern Spirit.! He is, to a degree, all of these. But, perhaps more significantly, he is an extension of his father's personality and temperament. In his essential loneliness and isolation, his hyper-sensitiv ity, his pessimistic outlook, and his suicidal bent, Father Time is clearly Jude Fawley's child. As such, he appropriately functions to advance the plot and to symbolize the significance of the mistakes Jude has made in the past. The similarity between Jude and Little Father Time is readily apparent. Sue is the first to comment on the likeness just after the boy comes to Aldbrickham to live with his father. -

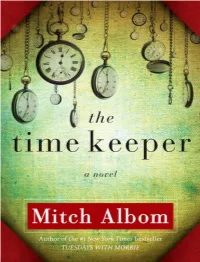

The Time Keeper.Pdf

Also by Mitch Albom Have a Little Faith For One More Day The Five People You Meet in Heaven Tuesdays with Morrie Fab Five Bo DEDICATION This book, about time, is dedicated to Janine, who makes every minute of life worthwhile. CONTENTS Also by Mitch Albom Title Page Dedication Prologue Chapter 1 Beginning Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 Chapter 16 Cave Chapter 17 Chapter 18 Chapter 19 Chapter 20 Chapter 21 Chapter 22 Chapter 23 The In-Between Chapter 24 Chapter 25 Chapter 26 Chapter 27 Chapter 28 Falling Chapter 29 Chapter 30 Chapter 31 Chapter 32 Earth Chapter 33 Chapter 34 Chapter 35 Chapter 36 Chapter 37 Chapter 38 Chapter 39 City Chapter 40 Chapter 41 Chapter 42 Chapter 43 Chapter 44 Chapter 45 Chapter 46 Chapter 47 Chapter 48 Chapter 49 Chapter 50 Chapter 51 Chapter 52 Chapter 53 Chapter 54 Letting Go Chapter 55 Chapter 56 Chapter 57 Chapter 58 Chapter 59 New Year’s Eve Chapter 60 Chapter 61 Chapter 62 Chapter 63 Stillness Chapter 64 Chapter 65 Chapter 66 Chapter 67 Chapter 68 Chapter 69 Future Chapter 70 Chapter 71 Chapter 72 Chapter 73 Chapter 74 Chapter 75 Chapter 76 Chapter 77 Chapter 78 Chapter 79 Epilogue Chapter 80 Chapter 81 Acknowledgments About the Author Copyright PROLOGUE 1 A man sits alone in a cave. His hair is long. His beard reaches his knees. He holds his chin in the cup of his hands. -

SLWP Writes! 2011

SLWP Writes! 2011 Edited by Jessica Kastner Writing Contest Sponsored by Southeastern Louisiana Writing Project Contents Prose Jacob Frick My Space ..................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Catherine Dunlap I’m Innocent ................................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Mathew Hill Fading to Black ........................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Josh Ortego Becoming Bob............................................................................................................................................................................. 11 Adam Breland A Twisted Fairy Tale ................................................................................................................................................................ 13 Sarah Smith Her Story................................................................................................................................................................................... 15 Poetry Catherine Dunlap The Fall of Adam........................................................................................................................................................................ 8 Mathew