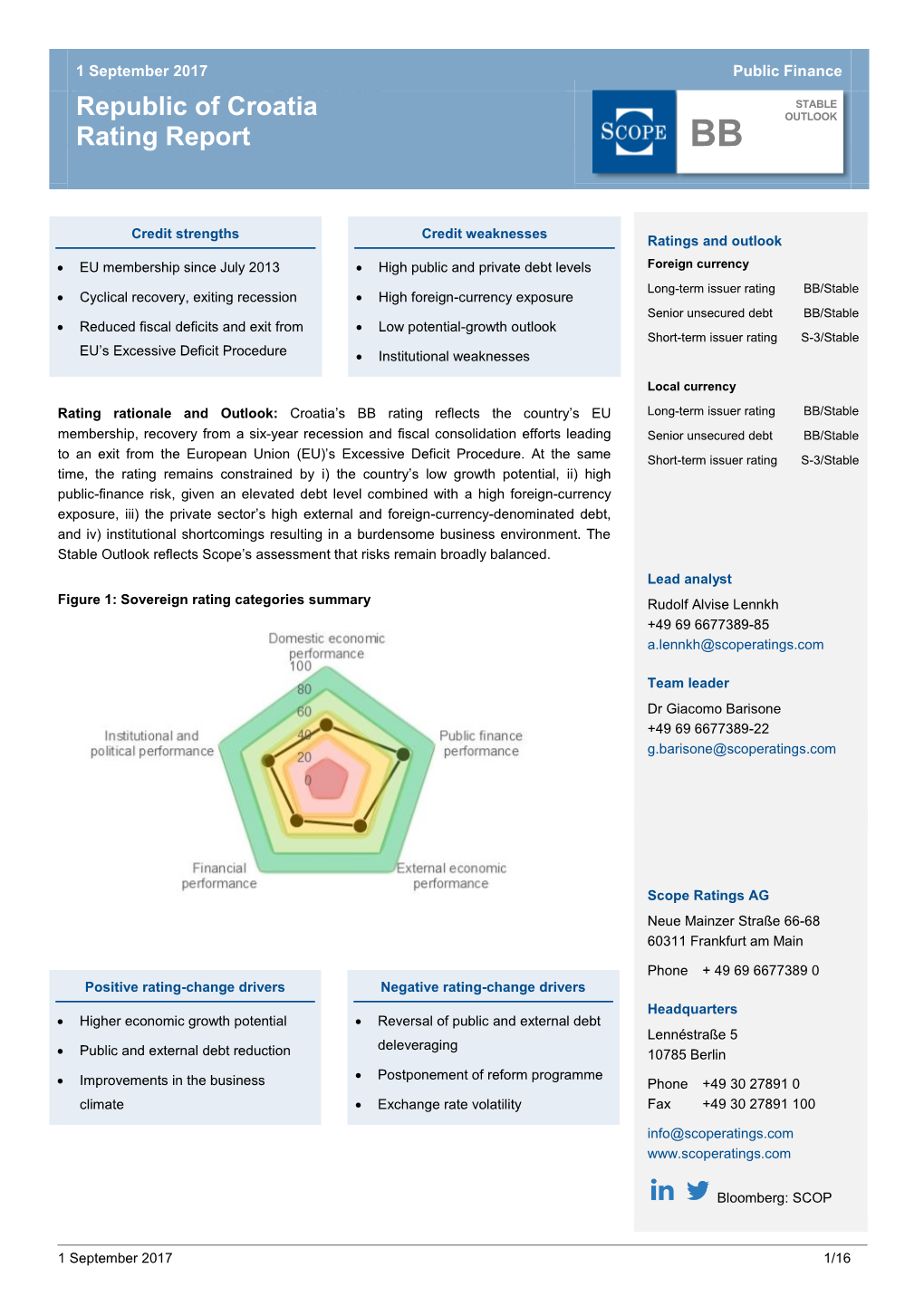

Rating Report BB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LÄNDERBERICHT Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung E.V

LÄNDERBERICHT Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. KROATIEN DR. MICHAEL A. LANGE 9. September 2015 Kandidaten positionieren und www.kas.de/kroatien Wahlbündnisse formieren sich PARLAMENTSWAHLEN IN KROATIEN Die Debatte um die Festsetzung des Wahl- überzeugt zeigt, auf, sich nicht weiter in termins für die anstehenden Parlaments- seinem Parteizentrale zu verkriechen son- wahlen in Kroatien kommt nicht zur Ruhe. dern sich endlich einer öffentlichen TV- Der kroatische Ministerpräsident Milano- Debatte zu stellen. vic unterstrich jüngst noch einmal, dass die aktuelle Legislaturperiode erst am 22. Aufbauend auf der Ankündigung eines be- Dezember endet und dass das kroatische vorstehenden Abschlusses einer Koalitions- Parlament in der verfassungsgemäß vor- vereinbarung seiner Partei mit den drei bis- gegebenen Frist aufgelöst werden wird, herigen Koalitionspartnern: der „Croatian sodass die Staatspräsidentin dann den People’s Party (HNS )“, der „Croatian Pensi- genauen Termin der Wahlen innerhalb der oners' Party ( HSU )“, der „Croatian Labou- 30-60 Tagefrist festlegen kann. Nach der rists ( HL )“ sowie der neuen „Autochthonous überraschenden Einberufung einer außer- Croatian Peasants’ Party ( AHSS )“, zeigte er ordentlichen Parlamentssitzung für den 8. sich optimistisch, was den Abschluss einer -11. September gehen viele politische Be- solchen Vereinbarung mit der sich diesbe- obachter nun davon aus, dass das Parla- züglich weiterhin zurückhaltenden „Istrian ment sich noch vor Ende September auf- Democratic Congress ( IDS )“ angeht. Nur lösen und damit der Staatspräsidentin den zusammen mit der IDS meint Milanovic Weg ebnen wird, einen Wahltermin zwi- Kroatien auf dem richtigen Weg halten zu schen Ende Oktober (25.) und Mitte No- können und bot deshalb allen politischen vember (1., 8. und 15.) zu bestimmen. Da Partnern bereits sichere Listenplätze an. -

Politicka Misao 4 2017.Indd

Croatian Political Science Review, Vol. 54, No. 4, 2017, pp. 61-84 61 Review Article Received: 15 May 2017 Gaining Political Power by Utilizing Opportunity Structures: An Analysis of the Conservative Religious-Political Movement in Croatia ANTONIJA PETRIČUŠIĆ, MATEJA ČEHULIĆ, DARIO ČEPO Chair of Sociology, Faculty of Law, University of Zagreb Summary This paper explores a connection between religion and politics in Croatia by analyzing the conservative civic initiative “In the Name of the Family” (U ime obitelji). It is a part of a broader religious-political movement, which emerged over the course of the last decade, that is connected to other international con- servative organizations and initiatives. They advocate for a decrease of secular influence on the family, oppose sexual and reproductive rights, and insist on the primacy of religious freedoms. The political nature of the movement mani- fests itself through multiple attempts to scrap the legislation and practices of both state and private institutions that are contradicting the value system of the Christian (Catholic) majority. The religious-political nexus of the movement is confirmed by its continuous involvement in policy-making, here manifested through the use of direct democracy institutes. Keywords: Religious-Political Movement, Contentious Politics, Opportunity Structure, Referendum, Same-Sex Marriage Introduction The referendum on the constitutional definition of marriage as a union between a man and a woman,1 held in December 2013, was the first successful national refe- rendum in Croatia initiated by a citizens’ initiative. “In the Name of the Family” (U ime obitelji) argued that the traditional values of Croatian society must be pro- tected through enshrining the traditional, heteronormative, definition of family. -

EUROPEAN POLITICAL PARTIES Contributions and Donations Related

EUROPEAN POLITICAL PARTIES Contributions and donations related to financial year 2018 The information below is published pursuant to Article 32(1)(e) and (f) of Regulation (EU, Euratom) No 1141/2014 Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Party Contributions from parties and political formations Contributor Country ALDE RO Alliance Party UK ANO 2011 CZ Centerpartiet SE Centerpartiet, Ȧland FI Ciudadanos ES Croatian People's Party - Liberal Democrats HR Darbo Partija LT Democraten 66 NL Demokratesch Partei LU Eesti Keskerakond EE Eesti Reformierakond EE FDP DE Fianna Fáil IE Glas HR Iniciativa Liberal PT HSLS HR 1 Contributor Country Istrian Democratic Assembly HR Keskusta FI Latvijas attistibai LV Liberal Democrats UK Liberal Party GI Liberalerna SE Liberalisok - Magyar Liberális Párt HU Liberals' Movement LT Mouvement Réformateur BE Movement for Rights and Freedoms BG NEOS AT Nowoczesna PL Open Vlaamse Liberalen en Democraten BE Pametno HR Partit Demokratiku MT PDeCAT ES Radicali Italiani IT Radikale Venstre DK SMC - Stranka Modernega Centra SI Svenska Folkpartiet FI Union of Democrats and Independents FR United Democrats CY Venstre Danmarks Liberale Parti DK Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie NL Zaveznistvo AB SI Total €417.294,64 Minor donations in accordance with Article 32(1)(e) Value Number of donors €12.682,00 486 2 Other donations Donor Country Value American Chamber of Commerce to the EU BE 6.000,00 Bayer AG DE 18.000,00 Deloitte to Deloitte Services & Investments NV BE 13.000,00 Eli Lilly Benelux SA BE 1.200,00 European -

EU Integration and Party Politics in the Balkans

EU integration and party politics in the Balkans EPC ISSUE PAPER NO. 77 SEPTEMBER 2 0 1 4 Edited by Corina Stratulat EUROPEAN POLITICS AND INSTITUTIONS ISSN 1782-494X PROGRAMME The EPC’s Programme on European Politics and Institutions With the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty, the new focus of this programme is on adapting the EU’s institutional architecture to take account of the changed set-up and on bringing the EU closer to its citizens. Continuing discussion on governance and policymaking in Brussels is essential to ensure that the European project can move forward and respond to the challenges facing the Union in the 21st century in a democratic and effective manner. This debate is closely linked to the key questions of how to involve European citizens in the discussions over its future; how to win their support for European integration and what are the prospects for, and consequences of, further enlargement towards the Balkans and Turkey. This programme focuses on these core themes and brings together all the strands of the debate on a number of key issues, addressing them through various fora, task forces and projects. It also works with other programmes on cross-cutting issues such as the reform of European economic governance or the new EU foreign policy structures. ii Table of Contents About the authors .................................................................................................................................... v List of tables ......................................................................................................................................... -

Republic of Croatia

REPUBLIC OF CROATIA €1,000,000,000 1.125 per cent. Notes due 2033 €1,000,000,000 1.750 per cent. Notes due 2041 Issue price for the 2033 Notes: 98.538 per cent. Issue price for the 2041 Notes: 99.366 per cent. The issue price of the €1,000,000,000 1.125 per cent. Fixed Rate Notes due 2033 (the "2033 Notes") issued by the Republic of Croatia (the "Issuer", the "Republic" or "Croatia"), will be 98.538 per cent. of their principal amount. The 2033 Notes will mature on 4 March 2033 at their principal amount. The issue price of the €1,000,000,000 1.750 per cent. Fixed Rate Notes due 2041 (the "2041 Notes" and, together with the 2033 Notes, the "Notes" and each a "Series") issued by the Issuer, will be 99.366 per cent. of their principal amount. The 2041 Notes will mature on 4 March 2041 at their principal amount. The 2033 Notes will be in registered form in denominations of €100,000 and integral multiples of €1,000 in excess thereof. Interest on the 2033 Notes will accrue at the rate of 1.125 per cent. per annum from and including 4 March 2021 and will be payable in Euro annually in arrear on 4 March in each year, commencing on 4 March 2022. Payments on the 2033 Notes will be made without withholding or deduction for or on account of taxes imposed by the Issuer except to the extent described under "Terms and Conditions of the 2033 Notes — Taxation". -

Central European University

TERRITORIAL DISPUTE BETWEEN CROATIA AND SLOVENIA IN THE BAY OF PIRAN: INTERPLAY OF INTERNATIONAL LAW AND INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS By Monika Suknaic Submitted to Central European University Department of International Relations and European Studies In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Supervisor: Professor Boldizsar Nagy Word Count: 14,845 CEU eTD Collection Budapest, Hungary 2010 ABSTRACT This research is concerned with the border dispute between Croatia and Slovenia and the role that international law plays in interstate politics and resolving disputes. The methodology used is a qualitative research paradigm of document analysis. The main findings of the research based on this case are that international law and international relations are mutually interdependent and it is impossible to resolve a dispute without applying both of them. Although they might seem clear, the international legal provisions can be understood in different ways by opposing parties, which is why disputes of this kind cannot be resolved without some sort of political compromise. CEU eTD Collection i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Firstly, I would like to thank my supervisor for all the support in trying to get to the bottom of sometimes complicated world of international law. Secondly, I would like to thank John Harbord for his daily following of my writing process. Finally, I am particularly thankful to my Budapest family who have been around for any kind of assistance, academic or personal. They know who they are. CEU eTD Collection ii -

Gendering Democratic Backsliding in Central and Eastern Europe. A

CENTER FOR POLICY STUDIES CENTRAL EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY Nádor utca 9., H–1051 Budapest, Hungary [email protected], http://cps.ceu.edu Published in 2019 by the Center for Policy Studies, Central European University © CEU CPS, 2019 ISBN 978-615-5547-07-2 (pdf) The views in this publication are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Central European University or the Research Executive Agency of the European Commission. This text may be used only for personal research purposes. Additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s), editor(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the year and the publisher. This publication has been produced in the framework of the project ‘Enhancing the EU’s Transboundary Crisis Management Capacities: Strategies for Multi-Level Leadership (TransCrisis)’. The project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme under grant agreement No 649484. Cover design: Borbala Soos Design & layout: Borbala Varga “Gendering Democratic Backsliding in Central and Eastern Europe is a must-read for anyone interested in the contemporary dynamics of illiberal democracies and reconfiguration of gender regimes. The theoretical introduction by Andrea Krizsán and Conny Roggeband displays great clarity and provides a neat structure for the whole volume. The book collects thick, but well nuanced and insightful analysis of recent developments of four CEE countries: Croatia, Hungary, Poland, and Romania. The case studies are fascinating, impressive for their richness, but thanks to the common analytical framework, the volume is consistent and accessible. -

Download File

LOCKED IN: THE SILENT SIEGE OF DUBROVNIK BY THE TOURISM INDUSTRY LAUREN A. RACUSIN COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE, PLANNING, and PRESERVATION URBAN PLANNING and HISTORIC PRESERVATION THESIS 2012 1 LOCKED IN: THE SILENT SIEGE OF DUBROVNIK BY THE TOURISM INDUSTRY Lauren A. Racusin Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degrees Master of Science in Historic Preservation Master of Science in Urban Planning Graduate School of Architecture, Planning, and Preservation COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY May 2012 ABSTRACT This thesis argues that Yugoslavia and an independent Croatia used Dubrovnik’s cultural heritage to define and substantiate themselves as they emerged from political upheaval, disrupted economies, and nascent institutional foundations and thus firmly embedded the tourism industry within their political economies as more than an economic tool. Through the tourism industry, the cultural heritage of Dubrovnik played a fundamental role, symboli- cally and economically, in their process of nation building. As an emblematic site of historic and national significance, Dubrovnik represented the freedom and wealth of culture that bothYugoslavia and Croatia as new unsteady political institutions sought to evoke. Within bolstering the tourism industry, Yugoslavia and Croatia cultivated Dubrovnik’s path dependency in the sector, which resulted in its contemporary “lock-in” and mono-economy. This study of Dubrovnik will elucidate the role of path dependency in shaping Dubrovnik’s economy, political actors, and -

PARLAMENTSWAHLEN in KROATIEN 2015 Dr. Michael Lange

PARLAMENTSWAHLEN IN KROATIEN 2015 Dr. Michael Lange INHALT: 1. Parlamentswahlen in Kroatien: Sommerliche Ruhe vor dem Sturm? (S. 3-11) 2. Wirtschaftliche Erholung oder patriotische Gesinnung? (S. 12-14) 3. Kandidaten positionieren und Wahlbündnisse formieren sich (S. 15-19) 4. Kroatien vor politischem Neubeginn? (S. 20-30) 5. Kopf an Kopf Rennen in Kroatien (S.31-38) 6. Überraschendes Patt lässt an Regierungsbildung zweifeln (S.39-46) 7. Überraschungssieger „MOST“ kompliziert Regierungsbildung (S.47-52) 8. Kroatien auf dem Weg zu Neuwahlen? (S.53-58) 9. MOST verhilft HDZ zur Mehrheit im kroatischen Parlament (S.59-64) 10. Neue kroatische Regierung gewinnt Vertrauensabstimmung (S.65-71) 11. 11. Die ersten 100 Tage der neuen kroatischen Regierung (71-84) 12. Anhang (85-119) 2 1. Parlamentswahlen in Kroatien - Sommerliche Ruhe vor dem Sturm? (24. Juli 2015) Im Juli 2015 regiert die „links-liberale“ Kukuriku-Koalition das Land seit nunmehr 44 Monaten und viele Bürger warten bis heute immer noch auf die zu Beginn der Amtszeit der neuen Regierung in Aussicht gestellten Reformen bzw. auf die von allen herbei gesehnte Verbesserung der wirtschaftlichen Situation des Landes. Viele mit dem EU Beitritt verbundenen Hoffnungen haben sich nicht erfüllt und viele kroatischen Bürger müssen feststellen, dass es ihrer Regierung bisher weder gelungen ist, aus dem EU-Beitritt unmittelbaren wirtschaftlichen Nutzen zu ziehen, noch dass es Anzeichen dafür gebe, dass das Land in naher Zukunft zu Wachstum und Prosperität zurückfinden werde. Entsprechend sehen viele Bürger die kommenden Parlamentswahlen als eine Möglichkeit zur Beendigung des Attentismus und zur politischen Weichenstellung, damit das Land sich möglichst schnell wieder auf den „rechten“ Weg begeben könne…. -

Croatia by Petar Dorić

Croatia by Petar Dorić Capital: Zagreb Population: 4.24 million GNI/capita, PPP: US$19,359 Source: World Bank’s World Development Indicators Nations in Transit Ratings and Averaged Scores 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2007 National Democratic 3.50 3.25 3.50 3.50 3.50 3.50 3.50 3.50 3.50 3.50 Governance Electoral Process 3.25 3.25 3.25 3.25 3.25 3.25 3.25 3.25 3.25 3.00 Civil Society 2.75 2.75 2.75 2.75 2.50 2.50 2.50 2.75 2.75 2.75 Independent Media 4.00 3.75 4.00 4.00 4.00 4.00 4.00 4.00 4.00 4.00 Local Democratic 3.75 3.75 3.75 3.75 3.75 3.75 3.75 3.75 3.75 3.75 Governance Judicial Framework 4.25 4.25 4.25 4.25 4.25 4.25 4.25 4.50 4.50 4.50 and Independence Corruption 4.75 4.50 4.50 4.50 4.25 4.00 4.00 4.00 4.00 4.25 Democracy Score 3.75 3.64 3.71 3.71 3.64 3.61 3.61 3.68 3.68 3.68 NOTE: The ratings reflect the consensus of Freedom House, its academic advisers, and the author(s) of this report. If consensus cannot be reached, Freedom House is responsible for the final ratings. The ratings are based on a scale of 1 to 7, with 1 representing the highest level of democratic progress and 7 the lowest. -

Factsheet: the Croatian Parliament

Directorate-General for the Presidency Directorate for Relations with National Parliaments Factsheet: The Croatian Parliament 1. At a glance Croatia is a republic and a parliamentary democracy. The Croatian Parliament is a unicameral body, following the abolition of the Chamber of Counties in March 2001. Currently the Assembly is composed of 151 Members. The Croatian Parliament is a representative body of citizens and is vested with the legislative power in the Republic of Croatia. It has been a democratic, multiparty legislature since 1990. MPs are elected directly by secret ballot based on universal suffrage for a term of four years. The current Croatian centre-right 13th Government is formed by the 'Patriotic coalition', which is headed by the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ) supported by the MOST alliance (Bridge of Independent Lists) as well as by the Milan Bandić 365 party. Mr Tihomir Orešković took office as the 11th Prime Minister on 22 January 2016. The incumbent President of Croatia is Mrs Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović (HDZ) sworn in on 15 February 2015 for a five years term. 2. Composition Results of the Croatian Parliament elections on 8 November 2015 Party EP affiliation % Seats Domoljubna koalicija: 'Patriotic Coalition' 39% 59 Hrvatska demokratska zajednica (HDZ) Croatian Democratic Union Hrvatska stranka prava dr. Ante Starčević (HSP) Croatian Party of Rights dr. Ante Starčević Hrvatska seljačka stranka (HSS) Croatian Peasant Party Hrvatska socijalno liberalna stranka (HSLS) Croatian Social Liberal Party Hrvatski rast (HRAST) -

Republic of Croatia

REPUBLIC OF CROATIA Outlook of the country Main general, political and economic summary of the country Embassy of the State of Israel to the Republic of Croatia Contents 1. ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL OVERVIEW 3 1.1. GENERAL INFORMATION 3 1.2. STATISTICAL OVERVIEW 3 1.3. POLITICAL OUTLINE 4-5 1.4. GOODS TRADE BETWEEN ISRAEL AND CROATIA 5 1.5. ECONOMIC INDICATORS 6-7 1.6. MAIN SECTORS OF INDUSTRY 7-8 1.7. ECONOMIC SCORES 8 1.8. CREDIT RATINGS 9 1.9. FOREIGN TRADE IN FIGURES 9-11 2. BUSINESS ENVIRONMENT 12 2.1. TAXATION – TAX RATES 12-14 2.2. INTELECTUAL PROPERTY 14-15 2.3. BUSINESS LAW 15-16 2.4. INDUSTRIAL AND COMMERCIAL STANDARDS 16 2.5. BUSINESS PRACTICES 16-17 3. BUYING AND SELLING 18 3.1. E-COMMERCE 18-19 3.2. THE DISTRIBUTION NETWORK 19 3.3. CUSTOMS 20-21 3.4. TRANSPORT 21-24 3.5. SUPPLIERS 24 4. STARTING A BUSINESS 31 1 4.1. LEGAL FORMS OF COMPANIES 31 4.2. WORKING CONDITIONS 31-32 4.3. COST OF LABOUR 32 5. INVESTING IN CROATIA 33 5.1. PROCEDURES RELATIVE TO FOREIGN INVESTMENT 33 5.2. INVESTMENT OPPORTUNITIES 33 5.3. WHAT TO CONSIDER IF YOU INVEST IN CROATIA 33-34 6. SOURCES OF GENERAL ECONOMIC INFORMATION 35 7. AGREEMENTS BETWEEN ISRAEL AND CROATIA 36-40 8. CROATIAN ECONOMY IN 2019 41-43 2 1. ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL OVERVIEW 1.1. GENERAL INFORMATION Capital: Zagreb Population (mil): 4.1 Local Currency: Croatian kuna (HRK or kn) Exchange Rate (LCU:US$): 6.6 Head of State: President – Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović Prime Minister – Andrej Plenković Country telephone code: +385 Country internet sufix: .hr 1.2.