Download and Cite Final Wording and Page Numbers At

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Western Mongolia

© Lonely Planet Publications 219 WESTERN MONGOLIA Western Mongolia With its raw deserts, glacier-wrapped mountains, shimmering salt lakes and hardy culture of nomads, falconry and cattle rustling, western Mongolia is a timeless place that fulfils many romantic notions of the classic ‘Central Asia’. Squeezed between Russia, Kazakhstan, China and the Mongol heartland, this region has been a historical transition zone of endless cultures, the legacy of which is a patchwork of peoples including ethnic Kazakhs, Dorvods, Khotons, Myangads and Khalkh Mongols. The Mongol Altai Nuruu forms the backbone of the region, a rugged mountain range that creates a natural border with both Russia and China. It contains many challenging and popular peaks for mountain climbers, some over 4000m, and is the source of fast-flowing rivers, most of which empty into desert lakes and saltpans. The region’s wild landscape and unique mix of cultures is known among adventure travel- lers and a small tourist infrastructure has been created to support them. Bayan-Ölgii leads the pack with its own clique of tour operators and drivers prepared to shuttle visitors to the mountains. But while aimag capitals are tepidly entering the 21st century, most of the region remains stuck in another age – infrastructure is poor and old-style communist think- ing is the norm among local officials. Despite the hardships, western Mongolia’s attractions, both natural and cultural, are well worth the effort. With time and flexibility, the region may well be the highlight of your trip. HIGHLIGHTS -

Argali (Ovis Ammon) Conservation in Western Mongolia and the Altai-Sayan

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2003 Argali (Ovis ammon) conservation in western Mongolia and the Altai-Sayan Ryan L. Maroney The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Maroney, Ryan L., "Argali (Ovis ammon) conservation in western Mongolia and the Altai-Sayan" (2003). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 6497. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/6497 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of Montana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. **Please check "Yes” or "No” and provide signature** Yes, I grant permission No, I do not grant permission Author’s Signature; Date: Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's explicit consent. 8/98 ARGALI ipvis ammon) CONSERVATION IN WESTERN MONGOLIA AND THE ALTAI SAYAN by Ryan L. Maroney B.A., New College, Sarasota, Florida, 1999 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science The University of Montana 2003 Approved by Chairperson Dean, Graduate School Date UMI Number: EP37298 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

Conservation of Argali (Ovis Ammon) in Mongolia and the Altai- Sayan

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com S C IEL N N C E C A/nr) E ^ I D I R E C T < BIOLOGICAL CONSERVATION ELSEVIER Biological Conservation 121 (2005) 231 241- WWW. eIsevier.com/Iocate/biocon Conservation of argali Ovis ammon in western Mongolia and the Altai-Sayan Ryan L. Maroney * International Resource Management Program, College of Forestry and Conservation, The University o f Montana, 32 Campus Drive 0576, Missoula, M T 59812, USA Received 8 December 2003; received in revised form 16 March 2004; accepted 30 April 2004 Abstract Management of argali in Mongolia historically has been tied to improving biological research and anti poaching- activities within the framework of trophy hunting. Argali populations in protected areas, where trophy hunting does not occur, have received little attention, and conservation or management plans for these areas generally do not exist. In this study, results from interviews with pastoralists in Siilkhemiin Nuruu National Park in western Mongolia indicate that local people revere argali and are generally aware of and support government protections, but may not be inclined to reduce herd sizes or discontinue grazing certain pastures for the benefit of wildlife without compensation. Because past protectionist approaches to argali conservation in western Mongolia and the greater Altai- Sayan ecoregion have not achieved effective habitat conservation or anti poaching- enforcement, alternative man agement policies should be considered. Results from this study suggest local receptiveness to management programs based on community involvement and direct benefit. © 2004 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Argali; Management; Conservation; Mongolia; Altai Sayan- 1. Introduction In recognition of these shortcomings, recent discus sions to reform Mongolia’s trophy hunting practices Management and conservation activities for argali have led to proposals for Community Based Wildlife (wild sheep) Ovis ammon in Mongolia historically have Management (CBWM) programs for trophy hunting been linked to trophy hunting. -

FP154: Mongolia: Aimags and Soums Green Regional Development Investment Program (ASDIP)

FP154: Mongolia: Aimags and Soums Green Regional Development Investment Program (ASDIP) Mongolia | ADB | B.28/02 24 March 2021 Part I: Gender Analysis/Assessment Approach and methodology Objectives A gender analysis and Gender Action Plan were prepared with the following objectives: • Analyze the gender and development legal framework, policies, programs and institutions • Detail the gender context and analyze the gender issues; • Analyze the potential benefits of the project in terms of gender; • Provide gender-specific project design recommendations; • Develop an Action Plan detailing budget/resources requirements and implementation arrangements. The detailed gender analysis is available in TRTA final report (volume VI, Section Gender Analysis and Gender Action Plan) Multi-level analysis Considering the wide scope of Tranche 1 of the MFF, with various projects involving different beneficiaries, the analysis was conducted at three levels: Within the urban development component (Output 1): • The ger areas redevelopment project. These pilot projects take place in the aimag centers, and the beneficiaries are the residents of the pilot streets and to a larger extent, the residents of the ger areas. • The inter-soum centers development. These projects take place in two soum centers: Umnogovi (Uvs) and Deluun (Bayan Ulgii). The beneficiaries are the residents of these two soum centers and the surrounding population using the facilities of these two soum centers. Within the regional agri-business development component (Outputs 2 & 3): • The regional agri-business development projects aim at developing the livestock industry and extending the value chain (economic development) while at the same time improving sustainable management of pastureland (green development) and herder’s inclusion in the value chain (inclusive development). -

Protection of the Natural and Cultural Heritage of the Mongolian Altai Ulikpan Beket Mongolian Academy of Sciences, [email protected]

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Erforschung biologischer Ressourcen der Mongolei Institut für Biologie der Martin-Luther-Universität / Exploration into the Biological Resources of Halle-Wittenberg Mongolia, ISSN 0440-1298 2012 Protection of the Natural and Cultural Heritage of the Mongolian Altai Ulikpan Beket Mongolian Academy of Sciences, [email protected] Hans D. Knapp Internationale Naturschutzakademie Insel Vilm, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biolmongol Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Biodiversity Commons, Biological and Physical Anthropology Commons, Environmental Sciences Commons, Nature and Society Relations Commons, Other Animal Sciences Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Beket, Ulikpan and Knapp, Hans D., "Protection of the Natural and Cultural Heritage of the Mongolian Altai" (2012). Erforschung biologischer Ressourcen der Mongolei / Exploration into the Biological Resources of Mongolia, ISSN 0440-1298. 32. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/biolmongol/32 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Institut für Biologie der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Erforschung biologischer Ressourcen der Mongolei / Exploration into the Biological Resources of Mongolia, ISSN 0440-1298 by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Copyright 2012, Martin-Luther-Universität Halle Wittenberg, Halle (Saale). Used by permission. Erforsch. biol. Ress. Mongolei (Halle/Saale) 2012 (12): 335–352 Protection of the natural and cultural heritage of the Mongolian Altai 1 U. Beket & H.D. Knapp Abstract The Altai-Sayan Ecoregion is known as a hotspot of biodiversity with large wilderness landscapes and a high rate of endemism in Central Asia and Siberia. -

Leveraging Tradition and Science in Disaster Risk Reduction in Mongolia - 3 (LTS3)

Mercy Corps LTS3 Final Report (September 2019 – November 2020) Leveraging Tradition and Science in Disaster Risk Reduction in Mongolia - 3 (LTS3) December 2020 FINAL REPORT (April 1, 2020- September 30, 2020) Agreement # 720FDA19GR00135 Submitted to: USAID Submitted by: Mercy Corps COUNTRY CONTACT HEADQUARTERS CONTACT Wendy Guyot Erik Mandell Country Director Program Officer Mercy Corps Mercy Corps PO Box 761 45 SW Ankeny Street Ulaanbaatar 79, Mongolia Portland, OR 97204 Phone: +976 9911 4204 Phone: +1.503.896.5000 [email protected] [email protected] 1 Mercy Corps LTS3 Final Report (September 2019 – November 2020) ACRONYMS AND TRANSLATIONS Aimag An administrative unit similar to a province or state ALAGAC Administration of Land Affairs, Geodesy and Cartography Bagh An administrative unit similar to a sub-county (sub-soum) DRR Disaster Risk Reduction DPP Disaster Protection Plan Dzud Environmental hazard that unfolds over several seasons and includes drought conditions in summer leading to poor forage availability and low temperatures, heavy snows and/or ice in winter, resulting in animal deaths from starvation or exposure. GAVS General Authority for Veterinary Services GoM Government of Mongolia Khural An elected decision-making body at the district, province and national level LEGS Livestock Emergency Guidelines and Standards LEMA Local Emergency Management Agency LTS Leveraging Tradition and Science in Disaster Risk Reduction in Mongolia MoJ Ministry of Justice MET Ministry of Environment and Tourism MOFALI Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Light Industry MULS Mongolian University of Life Science NAMEM National Agency of Meteorology and Environmental Monitoring NEMA National Emergency Management Agency NSO National Statistical Office OFDA Office of U.S. -

The Altai Mountains Biodiversity Conservation Strategy

The Altai Mountains Biodiversity Conservation Strategy Safeguarding the biological diversity and natural ecological processes of the Altai Mountains landscape alongside local livelihoods and economic development Adopted by the Aimag Governments of Uvs, Khovd, Bayan Olgii and Govi Altai To be followed and championed by government, developers, non-governmental organizations and local residents 1 List of Contents 1. Overview...............................................................................................................................4 2. The place and the people.....................................................................................................13 3. Biodiversity and Ecology....................................................................................................22 4. Human impacts and threats to biodiversity.........................................................................29 5. Biodiversity conservation-related policies and programmes..............................................34 6. Objectives and Actions ........................................................................................................53 List of References ....................................................................................................................79 List of some relevant websites.................................................................................................87 Annex 1 Population, Infrastructure and Economy..................................................................89 -

ARGALI {Ovis Ammon) CONSERVATION in WESTERN MONGOLIA and the ALTAI-SAYAN

ARGALI {Ovis ammon) CONSERVATION IN WESTERN MONGOLIA AND THE ALTAI-SAYAN by Ryan L. Maroney B.A., New College, Sarasota, Florida, 1999 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science The University of Montana 2003 Approved by Chairperson Dean, Graduate School Date Maroney, Ryan L., M.S., 2003 Resource Conservation ARGALI (Ovis ammon) CONSERVATION IN WESTERN MONGOLIA AND THE ALTAI-SAYAN Chairperson: Dr. Stephen Siebert Management of argali subspecies in Mongolia historically has been tied to improving biological research and anti-poaching activities within the framework of trophy hunting. Argali populations in areas where trophy hunting does not occur, such as protected areas, have received little attention, and conservation or management plans for these areas generally do not exist. Furthermore, diverse social and environmental conditions require bioregional and site-specific conservation strategies within a national argali management plan. In this study, results from interviews with pastoralists in Siilkhemiin Nuruu National Park in western Mongolia indicate that local people revere argali and are generally aware of and support government protections, but may not be inclined to reduce herd sizes or discontinue grazing certain pastures for the benefit of wildlife without compensation. A preliminary survey of argali distribution in the park also identified key winter forage areas upon which to focus management efforts. Because past protectionist approaches to argali conservation in western Mongolia and the greater Altai-Sayan ecoregion have not achieved effective range management or anti-poaching enforcement, alternative management policies should be considered. Results from this study suggest local receptiveness to management programs based on community involvement and direct benefit. -

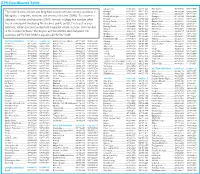

GPS Coordinates Table

GPS Coordinates Table Jiglegiin Am..................... 51º00.406 100º16.003 Mandalgov...................... 45º46.042 106º16.380 The table shows latitude and longitude coordinates for various locations in Khangal........................... 49º18.810 104º22.629 Mandal-Ovoo.................. 44º39.100 104º02.880 Khankh............................ 51º30.070 100º41.382 Manlai..............................44º04.441 106º51.703 Mongolia, in degrees, minutes and decimal minutes (DMM). To convert to Khar Bukh Balgas............. 47º53.198 103º53.513 Nomgon.......................... 42º50.160 105º08.983 degrees, minutes and seconds (DMS) format, multiply the number after Khatgal............................ 50º26.517 100º09.599 Ondorshil.........................45º13.585 108º15.223 Khishig-Öndör................. 48º17.678 103º27.086 Ongiin Khiid.....................45º20.367 104º00.306 the decimal point (including the decimal point) by 60. The result is your Khötöl..............................49º05.486 105º34.903 Orog Nuur....................... 45º02.692 100º36.314 seconds, which can be rounded to the nearest whole number. The minutes Khutag-Öndör................. 49º22.990 102º41.417 Saikhan-Ovoo..................45º27.459 103º54.110 Mogod.............................48º16.372 102º59.520 Sainshand.........................44º53.576 110º08.351 is the number between the degree symbol and the decimal point. For Mörön............................. 49º38.143 100º09.321 Sevrei...............................43º35.617 102º09.737 Orkhon........................... -

Integrated Water Resource Management Plan for Khar

INTRODUCTION LOCATION OF KHAR LAKE-KHOVD ENVIRONMENTAL STATE PROTECTED AREA NETWORK The Mongolian Law on Water was revised in 2004, RIVER BASIN Totally 2011,6 thousand hectare of the basin creating legal and regulatory framework for the establish- KHOVD BUYANT RIVER belongs to the existing Special Protected Area ment of broad based stakeholder representation through BASIN COUNCIL network. For instance, while the protected areas River Basin Council and introduction of Integrated Water Khar lake-Khovd river basin is a sub-basin of the Great Lakes’ Depres- e.g. Khukh Serkh Mountain range Strictly Protected Resource Management (IWRM). sion in Western Mongolia that belongs to the Central Asian internal basin. Khar lake-Khovd river basin is unique not only in Mongolia, but also in Area (SPA), Altai Tavan Bogd, Siilkhem Mountain range, Tsambagarav and Khar-Us lake National The Government of Mongolia pays special attention the world with its high mountains distributed by glaciers and permanent Parks (NP) and Mankhan and Devel Aral Nature to the integrated water resource management practice snow covers, deep and wide canoyns, valleys, forests, forest steppe, steppe, Reserves (NR) are entirely included in the basin, and has commenced some actions. For instance, the gobi and desert regions, a number of rivers, streams, lakes, and wetlands in a part (belonging to Munkh-khairkhan soum) of territory of Mongolia was divided into 29 river basins by the western part of the country. Munkh-khairkhan NP and a part (belonging to an order of the Minister for Nature, Environment and Occupied totally 86120.8 sq. km area, the Khar lake-Khovd river basin Bukhmurun soum) of Turgen Mountain SPA and an Tourism in 2009 to introduce IWRM. -

New Records of Water Beetles (Coleoptera: Gyrinidae, Haliplidae

Aquatic Insects International Journal of Freshwater Entomology ISSN: 0165-0424 (Print) 1744-4152 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/naqi20 New records of water beetles (Coleoptera: Gyrinidae, Haliplidae, Noteridae, Dytiscidae, Helophoridae, Hydrophilidae, Hydraenidae) and shore beetles (Coleoptera: Heteroceridae) of Mongolia Alexander A. Prokin, Gantigmaa Chuluunbaatar, Robert B. Angus, Manfred A. Jäch, Pyotr N. Petrov, Sergey K. Ryndevich, Enkhtuya Byambanyam, Alexey S. Sazhnev, Jiří Hájek & Helena Shaverdo To cite this article: Alexander A. Prokin, Gantigmaa Chuluunbaatar, Robert B. Angus, Manfred A. Jäch, Pyotr N. Petrov, Sergey K. Ryndevich, Enkhtuya Byambanyam, Alexey S. Sazhnev, Jiří Hájek & Helena Shaverdo (2020) New records of water beetles (Coleoptera: Gyrinidae, Haliplidae, Noteridae, Dytiscidae, Helophoridae, Hydrophilidae, Hydraenidae) and shore beetles (Coleoptera: Heteroceridae) of Mongolia, Aquatic Insects, 41:1, 1-44, DOI: 10.1080/01650424.2019.1651870 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/01650424.2019.1651870 Published online: 16 Oct 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 34 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=naqi20 AQUATIC INSECTS 2020, VOL. 41, NO. 1, 1–44 https://doi.org/10.1080/01650424.2019.1651870 New records of water beetles (Coleoptera: Gyrinidae, Haliplidae, Noteridae, Dytiscidae, Helophoridae, Hydrophilidae, Hydraenidae) and shore -

Proceedings of the Conference on Transformations, Issues, Livestock Numbers and Its Citizens’ Predominately Pastoral Liveli- and Future Challenges

Community Based Wildlife Management Planning in Protected Areas: the Case of Altai argali in Mongolia Ryan L. Maroney Ryan L. Maroney is a resource conservation and development coordinator with the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service in southwest Alaska’s Lower Kuskokwim River Region. He completed his undergraduate degree in environmental science at New College – the honors college of the Florida state system, and a M.S. degree in resource conservation through the University of Montana’s International Resource Management Program. As a U.S. Peace Corps volunteer, he worked for over two years in western Mongolia as an extension biologist with the Mongol Altai Nuruu Special Protected Areas Administration. Abstract—The number of protected areas in Mongolia has increased four- Introduction ____________________ fold since the country’s transition to a market-based economy over a decade ago; however, many of these protected areas have yet to realize their intended Following the 1992 transition from a command to market role as protectorates of biodiversity. Given the prevalence of (semi-) nomadic economy, Mongolia plunged into an economic depression from pastoralists in rural areas, effective conservation initiatives in Mongolia will which it has still not recovered. Over a third of Mongolians likely need to concurrently address issues of rangeland management and live in poverty and per capita income and GPD remain below livelihood security. The case of argali management in western Mongolia is 1990 levels (Finch 2002). During the last decade, foreign illustrative of a number of challenges facing protected areas management and wildlife conservation planning across the country. In this study, results from donor aid contributed on average 24 percent of GDP per interviews with pastoralists in a protected area in western Mongolia indicate year (Finch 2002), and Mongolia became one of the highest that local herders have a strong conservation ethic concerning the importance recipients of foreign aid dollars on a per capita basis (Anon.