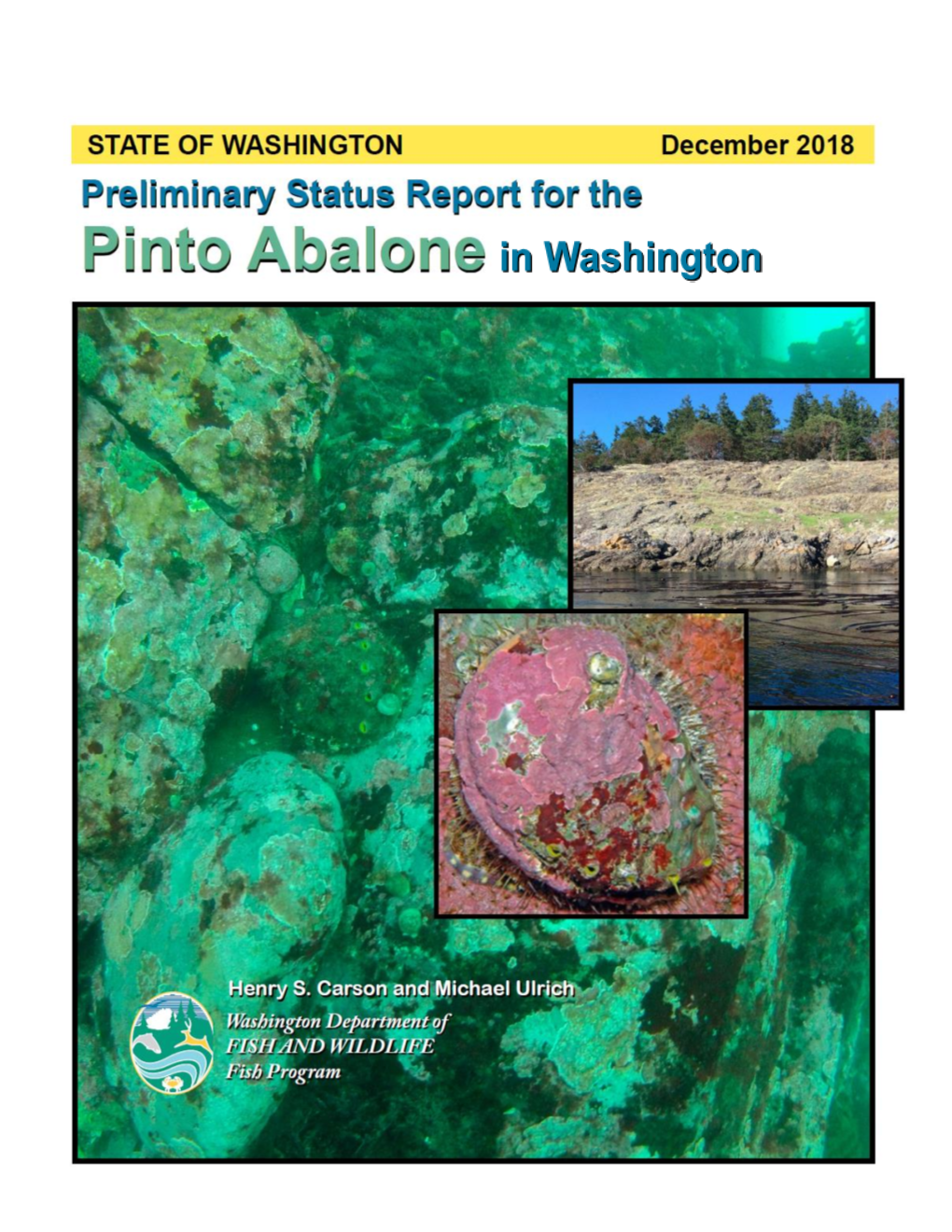

Preliminary Status Report for the Pinto Abalone in Washington

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Petition to Protect the Pinto Abalone

BEFORE THE SECRETARY OF COMMERCE PETITION TO LIST THE PINTO ABALONE (HALIOTIS KAMTSCHATKANA) UNDER THE ENDANGERED SPECIES ACT Center for Biological Diversity August 1, 2013 NOTICE OF PETITION Penny Pritzker Secretary of Commerce U.S. Department of Commerce 1401 Constitution Ave, NW Washington, D.C. 20230 Email: [email protected] Samuel Rauch Assistant Administrator for Fisheries National Marine Fisheries Service 1315 East West Highway Silver Spring, MD 20910 Ph: (301) 427-8000 Email: [email protected] PETITIONER The Center for Biological Diversity PO Box 100599 Anchorage, AK 99510-0599 Ph: (907) 793-8691 Date: August 1, 2013 Kiersten Lippmann Center for Biological Diversity Pursuant to Section 4(b) of the Endangered Species Act (“ESA”), 16 U.S.C. § 1533(b), Section 553(3) of the Administrative Procedures Act, 5 U.S.C. § 533(e), and 50 C.F.R. § 424.14(a), the Center for Biological Diversity (“Petitioner”) hereby petitions the Secretary of Commerce and the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (“NOAA”), through the National Marine Fisheries Service (“NMFS” or “NOAA Fisheries”), to list the pinto abalone (Haliotis kamtschatkana) as a threatened or endangered species and to designate critical habitat to ensure its survival and recovery. The Center for Biological Diversity (Center) is a non-profit, public interest environmental organization dedicated to the protection of native species and their habitats through science, policy, and environmental law. The Center has nearly 475,000 members and online activists in Alaska, throughout the United States and internationally. The Center and its members are concerned with the conservation of endangered species and the effective implementation of the ESA. -

The Importance and Persistence of Abalone (Haliotis Spp.) Along the California

The Importance and Persistence of Abalone (Haliotis spp.) along the California Coast Dr. Stevens ENVS 190 Senior Thesis Kalli Fenk Abstract Abalone was once a common sight along the California Coast. Native tribes co-existed with the species for thousands of years. They relied on if for sustenance and they used it for tools, utensils, jewelry, trading, and regalia. In return, they took care of the abalone as if it were one of their own. When colonization devastated Native Californian culture, much of their knowledge disappeared along with the species they cared for. Abalone was highly valuable for its taste and beauty. When commercialization of abalone fisheries began their populations began to decline. Now, they face more obstacles to recovery than ever before. Current abalone stressors include, poaching, low population densities, pollution, and disease. Warming ocean temperatures also subject abalone to sea level rise and ocean acidification. I recommend a combined approach of traditional ecological management and western science be used to provide adaptive management strategies for policy makers and fisheries managers. In preserving these creatures we are inherently preserving cultural heritage and traditions of over 20 tribes in California. Table of Contents Introduction……………………………………………………………………….1 Background………………………………………………………………………..2 Biology………………………………………………………………………3 Ecology……………………………………………………………………....4 Native History and Cultural Significance…………………………………...6 20th Century Population Declines…………………………………………..10 Current -

Reference List for 12-Month Finding on Two Petitions to List the Pinto Abalone (Haliotis Kamtschatkana) Under the Endangered Species Act

Reference List for 12-Month Finding on Two Petitions to List the Pinto Abalone (Haliotis kamtschatkana) under the Endangered Species Act National Marine Fisheries Service, West Coast Region Protected Resources Division, Long Beach, CA December 2014 FEDERAL REGISTER NOTICES U.S. Federal Register, Volume 68 No. 60. 68 FR 15100, March 28, 2003. Policy for evaluation of conservation efforts when making listing decisions. U.S. Federal Register, Volume 69 No. 73. 69 FR 19975, 15 April 2004. Endangered and threatened species; Establishment of Species of Concern list, addition of species to Species of Concern list, description of factors for identifying Species of Concern, and revision of candidate species list under the Endangered Species Act. U.S. Federal Register, Volume 78 No. 222. 78 FR 69033, 18 November 2013. Endangered and threatened wildlife: 90-day finding on petitions to list the pinto abalone as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act. U.S. Federal Register, Volume 79 No. 126. 79 FR 37578, 1 July 2014. Endangered and threatened wildlife: Final Policy on Interpretation of the Phrase ‘‘Significant Portion of Its Range’’ in the Endangered Species Act’s Definitions of ‘‘Endangered Species’’ and ‘‘Threatened Species.’’ PERSONAL COMMUNICATIONS Bird, Amanda. Masters Program, California State University, Fullerton (CSUF). July 26, 2014. Pers. comm. with Melissa Neuman (NMFS) regarding unpublished preliminary data from surveys to characterize the demographics of pinto abalone populations in nearshore San Diego kelp beds (Point Loma and La Jolla). Boch, Charles. Stanford University. April 28, 2014. Pers. comm. with David Kushner (NPS) regarding estimated proportion of H. kamtschatkana in mixed assemblages of H. -

White Abalone Recovery Plan

FINAL WHITE ABALONE RECOVERY PLAN (Haliotis sorenseni) Prepared by The White Abalone Recovery Team for National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Marine Fisheries Service Office of Protected Resources October 2008 RECOVERY PLAN FOR WHITE ABALONE (Haliotis sovenseni) Prepared by National Marine Fisheries Service Southwest Regional Office ~ationalwarineFisheries Service National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration White Abalone Recovery Plan DISCLAIMER DISCLAIMER Recovery plans delineate reasonable actions which are believed to be required to recover and/or protect listed species. Plans are published by the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), sometimes prepared with the assistance of recovery teams, contractors, state agencies, and others. Objectives will be obtained and any necessary funds made available subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views or the official positions or approval of any individuals or agencies involved in the plan formulation, other than NMFS. They represent the official position of NMFS only after they have been signed by the Assistant Administrator. Approved recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in species status and the completion of recovery actions. LITERATURE CITATION SHOULD READ AS FOLLOWS: National Marine Fisheries Service. 2008. White Abalone Recovery Plan (Haliotis sorenseni). National Marine Fisheries Service, Long Beach, CA. ADDITIONAL COPIES MAY BE OBTAINED FROM: United States Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Marine Fisheries Service, Southwest Regional Office 501 W. Ocean Blvd., Suite 4200 Long Beach, CA 90802-4213 On Line: http://swr.nmfs.noaa.gov/ Recovery plans can be downloaded from the National Marine Fisheries Service website: http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/pr/recovery/plans.htm Cover photograph of a white abalone by John Butler of the NOAA Southwest Fisheries Science Center. -

Haliotis Kamtschatkana) and Flat (Haliotis Walallensis) Abalones?

BULLETIN OF MARINE SCIENCE, 81(2): 283–296, 2007 IS CLIMATE CHANGE CONTRIBUTING TO RANGE REDUCTIONS AND LOCALIZED EXTINCTIONS IN NORTHERN (HALIOTIS KAMTSCHATKANA) AND FLAT (HALIOTIS WALALLENSIS) ABALONES? Laura Rogers-Bennett ABSTRACT Abalone abundance surveys from the 1970s were repeated 30 yrs later follow- ing a period of increased sea surface temperatures along the Pacific coast of the United States. Northern abalone, Haliotis kamtschatkana (Jonas, 1845) once abun- dant enough to support commercial fishing in Washington and Canada, are now extremely rare in the southern portion of their range in southern and central Cali- fornia. They have also declined 10 fold in northern California in the absence of hu- man fishing pressure. In Washington, northern abalone are in decline and exhibit recruitment failure despite closure of the fishery. Flat abalone, Haliotis walallensis (Stearns, 1899) no longer occur in southern California, and in central California have declined from 32% to 8% of the total number of abalones, Haliotis spp., inside a marine reserve. The distribution of flat abalone appears to have contracted over time such that they are now only common in southern Oregon where they are sub- ject to a new commercial fishery. Given these range reductions, the long-term per- sistence of flat abalone and northern abalone (locally) is a concern in light of threats from ocean warming, sea otter predation, and the flat abalone fishery in Oregon. The likelihood of future ocean warming poses challenges for abalone restoration, suggesting that improved monitoring and protection will be critical, especially in the northern portions of their distributions. Range shifts towards the poles have been documented for a number of species in meta-analyses and these shifts are consistent with predictions of global warming (Walther et al., 2002; Parmesan and Yohe, 2003; Root et al., 2003). -

Pubblicazione Mensile Edita Dalla Unione Malacologica Italiana

Distribution and Biogeography of the Recent Haliotidae (Gastropoda: Vetigastropoda) Worid-wide Daniel L. Geiger Autorizzazione Tribunale di Milano n. 479 del 15 Ottobre 1983 Spedizione in A.P. Art. 2 comma 20/C Legge 662/96 - filiale di Milano Maggio 2000 - spedizione n. 2/3 • 1999 ISSN 0394-7149 SOCIETÀ ITALIANA DI MALACOLOGIA SEDE SOCIALE: c/o Acquano Civico, Viale Gadio, 2 - 20121 Milano CONSIGLIO DIRETTIVO 1999-2000 PRESIDENTE: Riccardo Giannuzzi -Savelli VICEPRESIDENTE: Bruno Dell'Angelo SEGRETARIO: Paolo Crovato TESORIERE: Sergio Duraccio CONSIGLIERI: Mauro Brunetti, Renato Chemello, Stefano Chiarelli, Paolo Crovato, Bruno Dell’Angelo, Sergio Duraccio, Maurizio Forli, Riccardo Giannuzzi-Savelli, Mauro Mariani, Pasquale Micali, Marco Oliverio, Francesco Pusateri, Giovanni Repetto, Carlo Smriglio, Gianni Spada REVISORI DEI CONTI: Giuseppe Fasulo, Aurelio Meani REDAZIONE SCIENTIFICA - EDITORIAL BOARD DIRETTORE - EDITOR: Daniele BEDULLI Dipartimento di Biologia Evolutiva e Funzionale. V.le delle Scienze. 1-43100 Parma, Italia. Tel. + + 39 (521) 905656; Fax ++39 (521) 905657 E-mail : [email protected] CO-DIRETTORI - CO-EDITORS: Renato CHEMELLO (Ecologia - Ecology) Dipartimento di Biologia Animale. Via Archirafi 18. 1-90123 Palermo, Italia. Tel. + + 39 (91) 6177159; Fax + + 39 (9D 6172009 E-mail : [email protected] Marco OLIVERIO (Sistematica - Systematics) Dipartimento di Biologia Animale e dell’Uomo. Viale dell’Università 32. 1-00185 Roma, Italia. E-mail : [email protected] .it Italo NOFRONI (Sistematica - Systematict) Via Benedetto Croce, 97. 1-00142 Roma, Italia. Tel + + 39(06) 5943407 E-mail : [email protected] Pasquale MICALI (Relazioni con i soci - Tutor) Via Papina, 17. 1-61032 Fano (PS), Italia. Tel ++39 (0721) 824182 - Van Aartsen, Daniele Bedulli, Gianni Bello, Philippe Bouchet, Erminio Caprotti, Riccardo Catta- MEMBRI ADVISORS : Jacobus J. -

6.0 Report Preparation Sources

1 6.0 REPORT PREPARATION SOURCES 2 This section provides a comprehensive list of individuals who contributed to the 3 preparation of the Revised Analysis of Impacts to Public Trust Resources and Values 4 (APTR). 5 6.1 CSLC REPRESENTATIVES 6 Jason Ramos, Project Manager, Division of Environmental Planning and Management 7 (DEPM). 8 Cy Oggins, Chief, DEPM. 9 Eric Gillies, Assistant Chief, DEPM. 10 Kenneth Foster, Public Land Management Specialist, Land Management Division. 11 Seth Blackmon, Staff Counsel. 12 Shelli Haaf, Staff Counsel. 13 6.2 REVISED APTR PREPARERS Years Personnel Role Experience AMEC Dan Gira, Senior Program Manager 30 Project Manager Bronwyn Green, Project Manager 8 Deputy Project Manager Erika Leachman, Project Manager 8 Quality Control Doug McFarling, Senior Program Manager 19 Quality Control Aaron Goldschmidt, Practice Leader 17 Project Principal Rita Bright, Senior Land Use Specialist 23 Coastal Planner Melissa Busby, Senior Biologist 12 Terrestrial Biological Resources Ben Botkin, Environmental Scientist 4 Impact Analysis Nick Meisinger, Environmental Scientist/ 3 Terrestrial and Marine Biological Biologist Resources; Alternatives Shannon Moy, Environmental Scientist 3 Impact Analysis Sam White, Environmental Scientist 1 Impact Analysis Julia Pujo, Environmental Scientist 1 Impact Analysis Barry Snyder, Principal Aquatic Scientist 25 Coastal Processes, Alternatives Janice Depew, Publication Specialist 35 Document Production Deirdre Stites, Technical Illustrator 29 Graphic Arts Coastal Environments Hany Elwany, PhD, -

Haliotis Sorenseni)

California State University, Monterey Bay Digital Commons @ CSUMB Capstone Projects and Master's Theses 2010 Historic genetic diversity of the endangered white abalone (Haliotis sorenseni) Heather L. Hawk California State University, Monterey Bay Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes Recommended Citation Hawk, Heather L., "Historic genetic diversity of the endangered white abalone (Haliotis sorenseni)" (2010). Capstone Projects and Master's Theses. 67. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/caps_thes/67 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ CSUMB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Capstone Projects and Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ CSUMB. Unless otherwise indicated, this project was conducted as practicum not subject to IRB review but conducted in keeping with applicable regulatory guidance for training purposes. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HISTORIC GENETIC DIVERSITY OF THE ENDANGERED WHITE ABALONE (HALIOTIS SORENSEN!) A Thesis Presented to the Division of Science and Environmental Policy California State University Monterey Bay In Partial Fulfillment ofthe Requirements for the degree Master of Science In Marine Science by Heather L. Hawk December 2010 CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY MONTEREY BAY The Undersigned Faculty Committee Approves the Thesis of Heather L. Hawk: HISTORIC GENETIC DIVERSITY OF THE ENDANGERED WHITE ABALONE (HAL/OTIS SORENSEN!) Moss Landing Marine Laboratories ~dBurton SCRIPPS Institute ofOceanography Marsha Moroh, Dean College of Science, Media Arts, and Technology Copyright © 2010 Heather L. Hawk All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT HISTORIC GENETIC DIVERSITY OF THE ENDANGERED WHITE ABALONE (HALIOTIS SORENSEN!) by Heather L. Hawk Master of Science in Marine Science California State University Monterey Bay, 2010 In the 1970's, white abalone populations in California suffered catastrophic declines due to over-fishing, and the species has been listed under the Endangered Species Act since 2001. -

Marine Fisheries Management in a Changing Climate: a Review of Vulnerability and Future Options Johanna E

This article was downloaded by: [UQ Library] On: 05 July 2012, At: 17:25 Publisher: Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Reviews in Fisheries Science Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/brfs20 Marine Fisheries Management in a Changing Climate: A Review of Vulnerability and Future Options Johanna E. Johnson a & David J. Welch b c a C2O–coasts climate oceans, Townsville, Australia b Queensland Primary Industries and Fisheries, Townsville, Australia c Fishing and Fisheries Research Centre, School of Earth and Environmental Sciences, James Cook University, Townsville, Australia Version of record first published: 21 Jan 2010 To cite this article: Johanna E. Johnson & David J. Welch (2009): Marine Fisheries Management in a Changing Climate: A Review of Vulnerability and Future Options, Reviews in Fisheries Science, 18:1, 106-124 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10641260903434557 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. -

(Haliotis Kamtschatkana) and Flat (H. W

BULLETIN OF MARINE SCIENCE, 81(2): 283–296, 2007 IS CLIMATE CHANGE CONTRIBUTING TO RANGE REDUCTIONS AND LOCALIZED EXTINCTIONS IN NORTHERN (HALIOTIS KAMTSCHATKANA) AND FLAT (HALIOTIS WALALLENSIS) ABALONES? Laura Rogers-Bennett ABSTRACT Abalone abundance surveys from the 1970s were repeated 30 yrs later follow- ing a period of increased sea surface temperatures along the Pacific coast of the United States. Northern abalone, Haliotis kamtschatkana (Jonas, 1845) once abun- dant enough to support commercial fishing in Washington and Canada, are now extremely rare in the southern portion of their range in southern and central Cali- fornia. They have also declined 10 fold in northern California in the absence of hu- man fishing pressure. In Washington, northern abalone are in decline and exhibit recruitment failure despite closure of the fishery. Flat abalone, Haliotis walallensis (Stearns, 1899) no longer occur in southern California, and in central California have declined from 32% to 8% of the total number of abalones, Haliotis spp., inside a marine reserve. The distribution of flat abalone appears to have contracted over time such that they are now only common in southern Oregon where they are sub- ject to a new commercial fishery. Given these range reductions, the long-term per- sistence of flat abalone and northern abalone (locally) is a concern in light of threats from ocean warming, sea otter predation, and the flat abalone fishery in Oregon. The likelihood of future ocean warming poses challenges for abalone restoration, suggesting that improved monitoring and protection will be critical, especially in the northern portions of their distributions. Range shifts towards the poles have been documented for a number of species in meta-analyses and these shifts are consistent with predictions of global warming (Walther et al., 2002; Parmesan and Yohe, 2003; Root et al., 2003). -

Review of Fossil Abalone (Gastropoda: Vetigastropoda: Haliotidae) with Comparison to Recent Species Daniel L

J o x0)^ J. Paleont., 73(5), 1999, pp. 872-885 Copyright © 1999, The Paleontological Society 0022-3360/99/0073-0868$03.00 REVIEW OF FOSSIL ABALONE (GASTROPODA: VETIGASTROPODA: HALIOTIDAE) WITH COMPARISON TO RECENT SPECIES DANIEL L. GEIGER AND LINDSEY T. GROVES Department of Biological Sciences, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, 90089-0371, <[email protected]>, and Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, Sections of Malacology and Invertebrate Paleontology, 900 Exposition Boulevard, Los Angeles, CA 90007, <[email protected]> ABSTRACT—Compared to their Recent counterparts, fossil abalone are rare and poorly known. Their taxonomy is problematic, because most of the 35 fossil species have been described from single specimens and shell characteristics of Recent species are extremely plastic. Thus, the use of fossil species in phylogeny is questionable. Abalone first appear in the Upper Cretaceous (Maastrichian) with one species each in California and the Caribbean, are unknown in the Paleocene, and appear again in the late Eocene and Oligocene of New Zealand and Europe. They are regularly found from the late Miocene to the Recent in tropical to temperate regions worldwide. Most records are from intensely studied areas: SW North America, Caribbean, Europe, South Africa, Japan, and Australia. Despite their highest present-day diversity being found in the Indo-Pacific, their scarcity in the fossil record in this region is remarkable. The family may have originated in the central Indo-Pacific, Pacific Rim, or Tethys. An extensive list of all known fossil records including new ones from Europe and western North America is given. Fossil and Recent abalone both apparently lived in the shallow, rocky sublittoral in tropical and temperate climates. -

Commercial Fishing Digest

2021 California Commercial Fishing Regulations Digest For all commercial fishing in California Effective April 1, 2021 through March 31, 2022 CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF FISH AND WILDLIFE 2 2021 COMMERCIAL FISHING DIGEST Contents STATE OF CALIFORNIA Department of Fish and Wildlife Sales Office Locations ....................................................... 3 Gavin Newsom, Governor Foreword .............................................................................................................................................. 4 Updates for 2021 ...............................................................................................................................6 NATURAL RESOURCES AGENCY Fish Ticket Requirements ................................................................................................................................ 7 Wade Crowfoot, Secretary NOAA Fisheries Groundfish Trawl Catch Share Program .....................................................8 Prohibited Species ............................................................................................................................8 Department OF FISH AND WILDLIFE It Is Unlawful To: .................................................................................................................................9 Procedure for Opening and Closing Fisheries Charlton H. Bonham, Director Due to Toxins in Finfish or Invertebrates (FGC Section 5523) .............................................9 Federal And Other Regulations .................................................................................................