Scott Thurston, University of Salford

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ideas, 9 | Printemps / Été 2017 Cultural Imperialism Or Dialogue on Equal Terms? International Publications O

IdeAs Idées d'Amériques 9 | Printemps / Été 2017 Poètes et éditeurs : diffuser la poésie d'avant-garde américaine (depuis 1945) Cultural imperialism or dialogue on equal terms? International publications of innovative American poetry Impérialisme culturel ou dialogue entre égaux ? La publication internationale de la poésie nord-américaine expérimentale ¿Imperialismo cultural o diálogo entre iguales? Publicaciones internacionales de poesía estadounidense innovadora Manuel Brito Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ideas/2054 DOI : 10.4000/ideas.2054 ISSN : 1950-5701 Éditeur Institut des Amériques Référence électronique Manuel Brito, « Cultural imperialism or dialogue on equal terms? International publications of innovative American poetry », IdeAs [En ligne], 9 | Printemps / Été 2017, mis en ligne le 18 juillet 2017, consulté le 21 avril 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ideas/2054 ; DOI : 10.4000/ideas.2054 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 21 avril 2019. IdeAs – Idées d’Amériques est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Cultural imperialism or dialogue on equal terms? International publications o... 1 Cultural imperialism or dialogue on equal terms? International publications of innovative American poetry Impérialisme culturel ou dialogue entre égaux ? La publication internationale de la poésie nord-américaine expérimentale ¿Imperialismo cultural o diálogo entre iguales? Publicaciones internacionales de poesía estadounidense innovadora Manuel Brito Many thanks to the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation for its ongoing support of the Project (FFI 2009 10786) from which this essay comes. I also appreciate the IdeAs reviewers’ recommendations, which have definitely improved this essay. Introduction 1 It is true that the simple question “what is language?” has grounded most of the American poetic avant-garde since 1970. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy sutimitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorged copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9* black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. ProQuest Information and Leaming 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMÏ EIHETORICAL HYBRIDITY: ASHBERY, BERNSTEIN AND THE POETICS OF CITAHON DISSERTATION Presented in. Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy m the Graduate School o f The Ohio State University By \fatthew Richardson^ hlA . ***** The Ohio State Unwersity 2001 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Jon Erickson. Adviser Professor Jessica Prinz . -

In Early March 1981, Lyn Sent a Letter to Barrett, Bob, Charles Bernstein, Ron, and Steve, Proposing That Each Would Write A

In early March 1981, Lyn sent a letter to Barrett, Bob, Charles Bernstein, Ron, and Steve, proposing that each would write a page on a topic that she named, the whole to serve as an introduction to a selection of Language writings in French translation that would appear in Change magazine, as part of the March 1982 issue focused on “L’espace amérique,” edited (with an additional introduction) by Nanos Valaoritis. In 1989, our same six-person introduction was retranslated into Serbian and published in an issue of Delo, in Yugoslavia. Here is the six-person introduction. Ron Silliman, Barrett Watten, Steve Benson, Lyn Hejinian, Charles Bernstein, Bob Perelman Begun in the sixties, the writing of the American poets gathered here for Change matured into an organized, ongoing literary discourse in the following decade, a period of significant transition for the United States. From the perspective of capital, the war in Indochina was lost, a critical blow to national military prestige. More importantly, 1974 marked the end of capital’s longest “boom,” the expansionist years following the Second World War (on top of which the essential optimism of every variety of “New American” poetry had been constructed). Simultaneously, the largest generation in U.S. history, the “baby boom” of the 40’s and early 50’s, passed from college to the daily practices of material life. Tied to that generation and crippled from the beginning by its rejection of historical knowledge, the American New Left rapidly dissolved, although several of its veterans were to re-emerge as leaders of cross-class movements based on forms of personal oppression, as women or as gays of either sex. -

Z: • in ABOUT & AROUND LANGUAGE

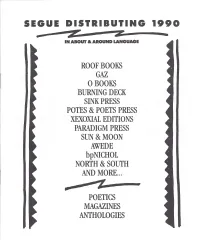

F--~~-~- SEGUE DISTRIBUTING 1990 $5 Z z: • IN ABOUT & AROUND LANGUAGE ROOF BOOKS GAZ oBOOKS BURNING DECK SINK PRESS POTES & POETS PRESS XEXOXIAL EDITIONS PARADIGM PRESS SUN &MOON AWEDE bpNICHOL NORTH & SOUTH AND MORE... .......~4__.. $I I- POETICS MAGAZINES ANTHOLOGIES p--------- FEATURED PRESSES ROOF BOOKS Raik by Ray DiPalma The one hundred poems in Ray DiPalma's new collection con The Politics ofPoetic Form: Poetry andPublic Policy tinue his experiments with the poetic line that began in the early Edited by Charles Bernstein 1970s with works such as The Sargasso Transcries, Soli, and Marquee, as well as the long lyric poem Planh. Raik articulates Acollection of 14 essays by contemporary poets and critics that the dynamic variety possible within the fixed form set for each expand on the discussions presented in L=A= N= G= U= poem in the book. A= G= E, focussing on the political and ideological dimensions of the formal and stylistic practices of contemporary poetry. There is a wide range of subject matter to be found here: the lyri These essays were originally presented at the Wolfson Center for cal qualities of Elizabethan underworld slang and the contem National Affairs of the New School for Social Research in New porary urban landscape; meditations on moments in history from York. Each essay is accompanied by an edited transcript of the ancient Egypt and Roman Britain to the Italian Renaissance. discussion that took place at the New School following the initial These choices of subject spotlight DiPalma's assiduous attention presentation. to details. The word choices in each poem stir awareness of each The Politics ofPoetic Form includes full-length essays by Jerome letter in the line. -

Essay Partly on the Tolerance Project by Stephen Voyce

TOWARD AN OPEN SOURCE POETICS: APPROPRIATION, COLLABORATION, AND THE COMMONS Author(s): Stephen Voyce Source: Criticism, Vol. 53, No. 3, Open Source (Summer 2011), pp. 407-438 Published by: Wayne State University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23133908 Accessed: 07-12-2017 20:53 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23133908?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Wayne State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Criticism This content downloaded from 165.123.34.86 on Thu, 07 Dec 2017 20:53:50 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms TOWARD AN OPEN SOURCE POETICS: APPROPRIATION, COLLABORATION, AND THE COMMONS Stephen Voyce Intellectual Property is the oil of the 21st century. —Mark Getty, Chairman of Getty Images (2000)' The new artistic paradigm is distribution. —Kenneth Goldsmith, word processor (2002)2 Software programmers first introduced the term open source to describe a model of peer production in which users are free to access, modify, and collaborate on software code. -

“Too Philosophical for a Poet”: a Conversation with Charles Bernstein

b2 Interview “Too Philosophical for a Poet”: A Conversation with Charles Bernstein Andrew David King ADK: I wanted to start by asking about the phenomenon of the book—as object and as commodity. In 2010, you spoke with Thom Donovan about the process and rationale behind putting together your selected poems, All the Whiskey in Heaven. Certain types of work (nonpoems; this is, of course, a tricky distinction) were excluded: the essays and libretti, for instance, whose presentations alongside poems in My Way unsettle more mainstream, big- publishing- house attitudes toward the compilation of written work. You said that the final product “has a very strong connection from beginning to end,” but that “it’s not in the way that the poems look, or the tone, or the style”: a connection, instead, in the “potentiating recombinations among parts,” which, at the same time, were linearly fused via your decision to exclude book titles from the text proper (making “a kind of text opera”—and there’s your libretto!) from the chronological selections, or, as the case may be, excerpts (Donovan 2010: n.p.). You recently released Recalculating, your first full- length volume of new poems in seven years, and so I wanted to Andrew David King and Charles Bernstein conducted this exchange by email from December 20, 2012, to March 7, 2015. boundary 2 44:3 (2017) DOI 10.1215/01903659- 3898094 © 2017 by Duke University Press Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/boundary-2/article-pdf/44/3/17/498982/BOU44_3_03King_Fpp.pdf by guest on 30 September 2021 18 boundary 2 / August 2017 know if there was anything significantly different for you about the act of putting a collection together now, after curating All the Whiskey in Heaven— or, alternatively, if there’s anything significantly different about the project of assembling a “new” collection versus a selected poems. -

2017-2018 HUMANITIES CENTER BROWN BAG SERIES Poetics As Value Thinking

2017-2018 HUMANITIES CENTER BROWN BAG SERIES Poetics as Value Thinking: The Example of ‘Plan B’ Barrett Watten, Professor, English Wednesday, April 4, 2018 12:30PM-1:30PM Rm. 2339 F/A Bldg This lecture is a hybrid of two thought experiments—one, a discussion of the poetics of value that sees political economy and poetics as twin forms of historically specific making, linked discourses of the determination of value. The second is a proposal for the transvaluation of poetics, and specifically Language and conceptual writing, as prospective organizations of poetic labor as a form of a“knowledge base” (adopted from information and digital theory). The notion that unites both is that poetry and poetics are forms not only of value making but value thinking—sites for the transvaluation of a general notion of value into particular values. Key forebears of the turn to a materialist poetics in modernism—Louis Zukofsky and William Carlos Williams above all—provide examples of poetry as value making in the widest sense. Zukofsky theorized a poetics of value in the making of his keystone work and parallel text, The First Half of “A.” Williams, early and late, shows how the making of the world is what counts as value, nowhere more readable than in the discontinuous unfolding, the uneven development of Paterson. In my second part, I propose how the poetics of Language and conceptual writing can be transvalued, from a static compiling of the data of language toward a transvaluation of the labor congealed in past production—language, poetry, and world. Just as experimental writing was a transvaluation of prior modes of poetry, leading to new values for writing, so the Barrett Watten transvaluation of experimental writing returns it to the world in its form of knowledge base, redefining the task of poetry and poetics as forms of value English thinking. -

AGENEALOGY Into the Company of Love It All Returns

THE LOST AMERICA OF LOVE: A GENEALOGY BARRETT WATTEN, WAYNE STATE UNIVERSITY Into the company of love it all returns. —Robert Creeley1 I This is apocryphal. A party in Hollywood, at which it was known that Liz would appear in the company of Eddie Fisher. Eddie is on the wane. Dick arrives, and while Liz and Dick have not yet consummated their love interest, the tension is electric. Having enjoyed as much of it as anyone can stand, it is time to leave. Liz has the look of one hypnotized, her car keys in her hand. Dick approaches, takes the keys. "You're my girl." "I'm your girl," she repeats, and they go out together. And from that day forward, for as long as it lasts, Eddie is out of the picture.2 Love beckons, and I decide. I want to account for a particular version of "love" in its intersection with poetry as a construction of postmodern American poetics: from its apex among postwar writers grouped together as the New American Poets to its decline and fall with poets of the succeeding generation, After the shipwreck, I managed to salvage only two texts from my extensive library—Sherman Paul's The Lost America of Love and my own Bad History, which I had in any case more or less com- mitted to memory. The Lost America of Love was a book I initially did not like when it was published, but there is nothing like free time on a desert island to reevaluate one's responses. And of course, many memories of my personal association with Paul at the University of Iowa in the early 1970s came back to me on rereading his work. -

Avant-Garde Haiku: a New Outlook Philip Rowland

Avant-Garde Haiku: A New Outlook Philip Rowland In a letter published in the Journal of the British Haiku Society, Blithe Spirit, in December 1998, Annie Bachini makes an interestingly provocative statement, amounting to a claim: “For myself,” she says, “I haven’t seen any examples of avant- garde haiku in English.” The immediate target of her letter is Caroline Gourlay’s allegedly too-blithe reference to “the traditional and the avant-garde” in the previous issue’s editorial. If, as Gourlay states, “the avant-garde and the traditional are, in fact, one and the same thing seen from different perspectives,” then in terms of Bachini’s assessment haiku in English would hardly seem to amount to a tradition at all. The basic problem is one of definition: what do we mean by “avant-garde”? And is the idea necessarily problematical? Gourlay’s statement is consistent with the Concise OED definition, “(of) pioneers or innovators in any art in a particular period” (my emphasis), which is all very well in hindsight—for, say, Debussy (Gourlay’s example) who has since become “regarded as the cornerstone of the post-romantic tradition”; but how are we to regard or even properly identify the avant-garde of the present period—especially difficult when the art-form itself is still at an early stage of recognition? Gourlay, commenting on Bachini’s letter, says that she finds “no shortage of English-language haiku that break the mould”—a mould, we can assume, of the sort described by the BHS consensus on “The Nature of English Haiku” (1996) (hereafter NEH). -

Adalaide Morris Fields Positions Awards and Fellowships

Adalaide Morris Department of English E-mail [email protected] University of Iowa date: February 2012 Iowa City, IA 52242 Fax: (319) 335-2535 Fields Modern and contemporary poetry and poetics Twentieth-century experimental writing New media poetics and pedagogy Positions 2000-10 John C. Gerber Professor of English 1985- Professor University of Iowa 1979-85 Associate Professor University of Iowa 1974-79 Assistant Professor University of Iowa 1973-74 Assistant Professor Georgetown University Awards and Fellowships Graduate College Outstanding Faculty Mentor Award, Arts and Humanities, 2011 John C. Gerber Distinguished Professorship in English, 2000-10 Regents’ Award for Faculty Excellence, 2007 Michael J. Brody Award for Faculty Excellence, 2000 Developmental Assignments, 2003-04 (postponed), 1999-2000, 1998-99 (postponed) CIC Academic Leadership Fellow, 1995-96 “Declensions,” Pushcart Prize nomination, 1994 Sonora Review Nonfiction Essay Prize, 1991 Visiting Fellow, Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University, Fall 1987 Senior Faculty Fellowship in the Humanities, University of Iowa, Spring 1987 American Association of University Women Fellowship, 1982-83 A.W. Mellon Foundation Publication Grant, Fall 1974 Phi Beta Kappa / B.A. magna cum laude with Distinction in English Memberships: Modernist Studies Association Executive Board (elected position), 2008-10, Membership and Communications Association of Departments of English ADE President January-December 2000 ADE Executive Committee December 1997-Dec. 2000 ADE Subcommittee on Staffing, 1998-2000, 2007-09 ADE Ad Hoc Commission on Staffing, 1996-98 Modern Languages Association MLA Staffing Commission, 2007-08 MLA Nominating Committee, elected position, 2007-08 Executive Committee, Division of Poetry, 2003-2007 2 Chair, 2006-2007 MLA English-Foreign Language Conference Planning Committee, Spring 2001-2002. -

GARDNER the Dwelling-Place

‘The Dwelling-Place’: Roland Barthes and the Birth of Language Poetry Calum Gardner o say that the work of Roland Barthes influenced the development T of the writers known broadly as the ‘language poets’ is a critical commonplace. It is not hard to see how this conclusion has been drawn: a lengthy quotation from Writing Degree Zero takes up the front page of the second issue of the magazine L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E, around which discussions of the movement have long coalesced, and his name appears throughout their collective body of work. To say only that ‘Barthes influenced language poetry’, however, is an oversimplification, avoiding the kind of interrogation of ‘influence’ that Barthes’ work itself demands. This article examines the relationship between Barthes’ texts and the episode in publishing history which might be taken as the ‘birth’ of ‘language poetry’: the mini-anthology ‘The Dwelling-Place’, edited by Ron Silliman. There, for the first time, a ‘language-centred tendency’ was first identified; indeed, it was self-identified, Silliman positioning himself as, and going on to become, a central member. At that moment of definition and origin, Barthes was present: Writing Degree Zero provides the name of the anthology, and his theory the basis of Silliman’s brief accompanying essay, ‘Surprised by Sign’. I shall identify here why Barthes was so important, what he offered to language writing, and what we can learn about both this poetry and about Barthes by reading them in the way Silliman first suggested in 1975. In the 1970s, a group of writers arose who reacted against both confessional poetry and even the more experimental ‘New American Poetry’ which encompassed Robert Duncan and Jack Spicer as well as the New York and Black Mountain schools. -

Questions of Poetics: Language Writing and Consequences

BOOK NEWS from the University of Iowa Press • 100 Kuhl House • Iowa City, IA 52242 For Immediate Release: July 2016 Media Contact: James McCoy, Director 319-335-2013, [email protected] Questions of Poetics: Language Writing and Consequences Iowa City, IA—Questions of Poetics is Barrett Watten’s major reassessment of the political history, social formation, and literary genealogy of Language writing. A key participant in the emergent bicoastal poetic avant-garde as poet, editor, and publisher, Watten has developed, over three decades of writing in poetics, a sustained account of its theory and practice. The present volume represents the core of Watten’s critical writing and public lecturing since the millennium, taking up the historical origins and continuity of Language writing from its beginnings to the present. Each chapter is a theoretical inquiry into an aspect of poetics in an expanded sense—from the relation of experimental poetry to cultural logics of Questions of Poetics liberation and political economy, to questions of community and the politics of Language Writing and Consequences the avant-garde, to the cultural contexts where it is produced and intervenes. BARRETT WATTEN Each serves as a kind of thought experiment that theorizes and assesses the consequences of Language writing in expanded fields of meaning that include Questions of Poetics: Language history, political theory, art history, and narrative theory. While all are grounded in Writing and Consequences a series of baseline questions of poetics, they also polemically address the currently by Barrett Watten turbulent debates on the politics of the avant-garde, especially Language writing, Contemporary North American Poetry Series among emerging communities of poets.