GARDNER the Dwelling-Place

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ideas, 9 | Printemps / Été 2017 Cultural Imperialism Or Dialogue on Equal Terms? International Publications O

IdeAs Idées d'Amériques 9 | Printemps / Été 2017 Poètes et éditeurs : diffuser la poésie d'avant-garde américaine (depuis 1945) Cultural imperialism or dialogue on equal terms? International publications of innovative American poetry Impérialisme culturel ou dialogue entre égaux ? La publication internationale de la poésie nord-américaine expérimentale ¿Imperialismo cultural o diálogo entre iguales? Publicaciones internacionales de poesía estadounidense innovadora Manuel Brito Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ideas/2054 DOI : 10.4000/ideas.2054 ISSN : 1950-5701 Éditeur Institut des Amériques Référence électronique Manuel Brito, « Cultural imperialism or dialogue on equal terms? International publications of innovative American poetry », IdeAs [En ligne], 9 | Printemps / Été 2017, mis en ligne le 18 juillet 2017, consulté le 21 avril 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ideas/2054 ; DOI : 10.4000/ideas.2054 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 21 avril 2019. IdeAs – Idées d’Amériques est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Cultural imperialism or dialogue on equal terms? International publications o... 1 Cultural imperialism or dialogue on equal terms? International publications of innovative American poetry Impérialisme culturel ou dialogue entre égaux ? La publication internationale de la poésie nord-américaine expérimentale ¿Imperialismo cultural o diálogo entre iguales? Publicaciones internacionales de poesía estadounidense innovadora Manuel Brito Many thanks to the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation for its ongoing support of the Project (FFI 2009 10786) from which this essay comes. I also appreciate the IdeAs reviewers’ recommendations, which have definitely improved this essay. Introduction 1 It is true that the simple question “what is language?” has grounded most of the American poetic avant-garde since 1970. -

Ron Silliman

© 2007 UC Regents Buy this book UC-Silliman 12/18/06 3:29 PM Page iv University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 2007 by The Regents of the University of California Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Silliman, Ronald, 1946–. [Age of huts] The age of huts (compleat) / Ron Silliman. p. cm. — (New California poetry ; 21) This title is one of a four-part poem cycle, which is entitled Ketjak. The parts are: The age of huts, Tjanting, The alphabet, & Universe. isbn: 978-0-520-25014-7 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn: 978-0-520-25016-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) I. Silliman, Ronald, 1946– Ketjak. II. Title. ps3569.i445a7 2007 811'.54—dc22 2006025507 Manufactured in Canada 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 07 10987654321 This book is printed on New Leaf EcoBook 50, a 100% recycled fiber of which 50% is de-inked post-consumer waste, processed chlorine-free. EcoBook 50 is acid-free and meets the minimum requirements of ansi/astm d5634–01 (Permanence of Paper). UC-Silliman 12/18/06 3:29 PM Page vii Contents Preface ix Acknowledgments xi Ketjak / 1 Sunset Debris / 103 The Chinese Notebook / 147 -

Eigner Preface

Charles Bernstein: Foreword to Selected Poems of Larry Eigner (forthcoming, University of Alabama Press) The Imagined, Returning: Larry Eigner’s Endless Song Larry Eigner was born in Lynn, Massachusetts on August 7, 1927 and spent most of his life in nearby Swampscott, midway between Boston and Gloucester, just a few blocks from the ocean. Eigner lived in his parents’ house in Swampscott until 1978, when, shortly after his father’s death, he moved to Berkeley, where he lived until his death in 1996. These facts are bare, commensurate to Eigner’s poems, which bear witness to the preternatural spareness of his life, just as they bear the weight of a gravitational aesthetic force field unprecedented in American poetry. That’s an extravagant claim for a poet who averted extravagance. And it’s an incredible claim too, given Eigner’s obscurity: despite legions of fervent readers, Eigner’s magisterial four-volume, almost 2000-page Collected Poems, received virtually no public recognition when it was published by Stanford University Press in 2010. With this volume, Collected editors Robert Grenier and Curtis Faville have created a perfectly scaled introduction to the full scope of Eigner’s work.* To be an obscure poet is not to be obscure, to invert John Ashbery’s quip that a famous poet is not famous. Eigner’s work has made an indelible impact among the generation of poets brought together in the iconic 1960 New American Poetry anthology. Eigner’s poetry was recognized early on by Robert Creeley, Charles Olson, Denise Levertov, and Cid Corman and was subsequently published by hundreds of small press editors in pamphlets, books, and magazines. -

LANGUAGE POETRY Entry for the Greenwood Encyclopedia of American Poetry (2005)

Craig Dworkin: LANGUAGE POETRY Entry for The Greenwood Encyclopedia of American Poetry (2005) The discrepancy between the number of people who hold an opinion about Language Poetry and those who have actually read Language Poetry is perhaps greater than for any other literary phenomenon of the later twentieth century. For just one concrete indicator of this gap, a primer on "The Poetry Pantheon" in The New York Times Magazine (19 February, 1995) listed Paul Hoover, Ann Lauterbach, and Leslie Scalapino as the most representative “Language Poets” — a curious choice given that neither Hoover nor Lauterbach appears in any of the defining publications of Language Poetry, and that Scalapino, though certainly associated with Language Poetry, was hardly a central figure. Indeed, only a quarter-century after the phrase was first used, it has often come to serve as an umbrella term for any kind of self-consciously "postmodern" poetry or to mean no more than some vaguely imagined stylistic characteristics — parataxis, dryly apodictic abstractions, elliptical modes of disjunction — even when they appear in works that would actually seem to be fundamentally opposed to the radical poetics that had originally given such notoriety to the name “Language Poetry” in the first place. The term "language poetry" may have first been used by Bruce Andrews, in correspondence from the early 1970s, to distinguish poets such as Vito Hannibal Acconci, Carl Andre, Clark Coolidge, and Jackson Mac Low, whose writing challenged the vatic aspirations of “deep image” poetry. In the tradition of Gertrude Stein and Louis Zukofksy, such poetry found precedents in only the most anomalous contemporary writing, such as John Ashbery's The Tennis Court Oath, Aram Saroyan's Cofee Coffe, Joseph Ceravolo's Fits of Dawn, or Jack Kerouac's Old Angel Midnight. -

The Birth of Linguistically Innovative Poetry and the Practice of a Collective Poetics in Robert Sheppard’S Pages and Floating Capital Thurston, SD

“For which we haven’t yet a satisfactory name” : the birth of Linguistically Innovative Poetry and the practice of a collective poetics in Robert Sheppard’s Pages and Floating Capital Thurston, SD Title “For which we haven’t yet a satisfactory name” : the birth of Linguistically Innovative Poetry and the practice of a collective poetics in Robert Sheppard’s Pages and Floating Capital Authors Thurston, SD Type Book Section URL This version is available at: http://usir.salford.ac.uk/id/eprint/48250/ Published Date 2019 USIR is a digital collection of the research output of the University of Salford. Where copyright permits, full text material held in the repository is made freely available online and can be read, downloaded and copied for non-commercial private study or research purposes. Please check the manuscript for any further copyright restrictions. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. 1 “For which we haven’t yet a satisfactory name”: The Birth of Linguistically Innovative Poetry and the Practice of a Collective Poetics in Robert Sheppard’s Pages and Floating Capital. In July 1987 Robert Sheppard published the first issue of a little magazine called Pages. The magazine was a humble affair, comprised of four folded A4 sheets to give eight printed pages per issue. Typescript material was pasted into camera ready copy format and photocopied.1 The editorial opens: Anybody concerned for a viable poetry in Britain must be depressed by the persistence of the Movement Orthodoxy from the 1950s into the late 80s; by its consolidation of power for a bleak future; by its neutralising assimilation of the surfaces of modernism; by its annexation of the increasingly fashionable term postmodernism; and by its ignorance – real or affected – of much of the work of the British Poetry Revival.2 This is very much a downbeat tone on which to begin a new enterprise. -

Combating Conventional Realism and Commodity Fetishism In

International Journal of Linguistics andLiterature (IJLL) ISSN(P): 2319-3956; ISSN(E): 2319-3964 Vol. 7, Issue 5, Aug – Sep 2018; 33-48 © IASET COMBATING CONVENTIONAL REALISM AND COMMODITYFETISHISM IN REPRESENTATION OF EVERYDAY LIFE: ASTUDY OF RON SILLIMAN’S BART ON BART Abeer M. Refky M. Seddeek College of Language and Communication (CLC), Arab Academy for Science, Technology and Maritime Transport (AASTMT), Alexandria, Egypt ABSTRACT The aim of this paper is twofold; first it explains Everyday Life and Cultural Theory as based on the studies of Michael Sheringham, Ben Highmore, Guy Debord and the Situationists, and Henri Lefebvre. It shows that la vie quotidienneresists categorization and requires various forms of representation and discourse to reflect its continuum. It explains Everyday Life Theory concern with urban geography and the dérive technique as well as the dominance of Capitalism commodity fetish that commodified and stamped with value the social and political aspects, even language. Secondly, the paper discusses Ron Silliman’s BART on Bart’s (1982) probing of the quotidian through its structure that is based on accumulation, repetition, juxtaposition and extreme length, the new sentence and procedural constraint as means of describing the real. It shows the city as a whole in movement to explain the continuum of the everyday. The paper concludes that BART on Bart negates conventional realism and the capitalistic approach of commodification. KEYWORDS: Capitalism – Everyday Life and Cultural Theory – Marx’s Commodity Fetish – Realism – Situationism Article History Received: 08 Aug 2018 | Revised: 17 Aug 2018 | Accepted: 23 Aug 2018 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Significance of Study Language poetry, which emerged in the United States at the end of the 1960s and early 1970s, changes the poetic language from customary discourse. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy sutimitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorged copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9* black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. ProQuest Information and Leaming 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMÏ EIHETORICAL HYBRIDITY: ASHBERY, BERNSTEIN AND THE POETICS OF CITAHON DISSERTATION Presented in. Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy m the Graduate School o f The Ohio State University By \fatthew Richardson^ hlA . ***** The Ohio State Unwersity 2001 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Jon Erickson. Adviser Professor Jessica Prinz . -

In Early March 1981, Lyn Sent a Letter to Barrett, Bob, Charles Bernstein, Ron, and Steve, Proposing That Each Would Write A

In early March 1981, Lyn sent a letter to Barrett, Bob, Charles Bernstein, Ron, and Steve, proposing that each would write a page on a topic that she named, the whole to serve as an introduction to a selection of Language writings in French translation that would appear in Change magazine, as part of the March 1982 issue focused on “L’espace amérique,” edited (with an additional introduction) by Nanos Valaoritis. In 1989, our same six-person introduction was retranslated into Serbian and published in an issue of Delo, in Yugoslavia. Here is the six-person introduction. Ron Silliman, Barrett Watten, Steve Benson, Lyn Hejinian, Charles Bernstein, Bob Perelman Begun in the sixties, the writing of the American poets gathered here for Change matured into an organized, ongoing literary discourse in the following decade, a period of significant transition for the United States. From the perspective of capital, the war in Indochina was lost, a critical blow to national military prestige. More importantly, 1974 marked the end of capital’s longest “boom,” the expansionist years following the Second World War (on top of which the essential optimism of every variety of “New American” poetry had been constructed). Simultaneously, the largest generation in U.S. history, the “baby boom” of the 40’s and early 50’s, passed from college to the daily practices of material life. Tied to that generation and crippled from the beginning by its rejection of historical knowledge, the American New Left rapidly dissolved, although several of its veterans were to re-emerge as leaders of cross-class movements based on forms of personal oppression, as women or as gays of either sex. -

A Network Analysis of Postwar American Poetry in the Age of Digital Audio Archives Ankit Basnet and James Jaehoon Lee

Journal of April 20, 2021 Cultural Analytics A Network Analysis of Postwar American Poetry in the Age of Digital Audio Archives Ankit Basnet and James Jaehoon Lee Ankit Basnet, University of Cincinnati James Lee, University of Cincinnati Peer-Reviewer: Stephen Voyce Data Repository: 10.7910/DVN/NK7Z2H A B S T R A C T From the New American Poetry to New Formalism, publishing networks such as literary magazines and social scenes such as poetry reading series have served as a capacious model for understanding the varied poetic formations in the postwar period. As audio archives of poetry readings have been digitized in large volumes, Charles Bernstein has suggested that open access to digital archives allows readers of American poetry to create mixtapes in different configurations. Digital archives of poetry readings “offer an intriguing and powerful alternative” to organizing practices such as networks and scenes. Placing Bernstein’s definition of the digital audio archive into contact with more conventional understandings of poetic community gives us a composite vision of organizing principles in postwar American poetry. To accomplish this, we compared poetry reading venues as well as audio archives — alongside more familiar print networks constituted by poetry anthologies and magazines — as important and distinct sites of reception for American poetry. We used network analysis to visualize the relationships of individual poets to venues where they have read, archives where their readings are stored, and text anthologies where their poetry has been printed. Examining several types of poetic archives offers us a new perspective in how we perceive the relationships between poets and their “networks and scenes,” understood both in terms of print and audio culture, as well as trends and changes in the formation of these poetic communities and affiliations. -

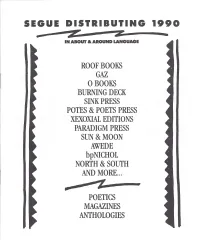

Z: • in ABOUT & AROUND LANGUAGE

F--~~-~- SEGUE DISTRIBUTING 1990 $5 Z z: • IN ABOUT & AROUND LANGUAGE ROOF BOOKS GAZ oBOOKS BURNING DECK SINK PRESS POTES & POETS PRESS XEXOXIAL EDITIONS PARADIGM PRESS SUN &MOON AWEDE bpNICHOL NORTH & SOUTH AND MORE... .......~4__.. $I I- POETICS MAGAZINES ANTHOLOGIES p--------- FEATURED PRESSES ROOF BOOKS Raik by Ray DiPalma The one hundred poems in Ray DiPalma's new collection con The Politics ofPoetic Form: Poetry andPublic Policy tinue his experiments with the poetic line that began in the early Edited by Charles Bernstein 1970s with works such as The Sargasso Transcries, Soli, and Marquee, as well as the long lyric poem Planh. Raik articulates Acollection of 14 essays by contemporary poets and critics that the dynamic variety possible within the fixed form set for each expand on the discussions presented in L=A= N= G= U= poem in the book. A= G= E, focussing on the political and ideological dimensions of the formal and stylistic practices of contemporary poetry. There is a wide range of subject matter to be found here: the lyri These essays were originally presented at the Wolfson Center for cal qualities of Elizabethan underworld slang and the contem National Affairs of the New School for Social Research in New porary urban landscape; meditations on moments in history from York. Each essay is accompanied by an edited transcript of the ancient Egypt and Roman Britain to the Italian Renaissance. discussion that took place at the New School following the initial These choices of subject spotlight DiPalma's assiduous attention presentation. to details. The word choices in each poem stir awareness of each The Politics ofPoetic Form includes full-length essays by Jerome letter in the line. -

Ron Silliman Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf696nb4f8 No online items Ron Silliman Papers Finding aid prepared by Special Collections & Archives Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla, California, 92093-0175 858-534-2533 [email protected] Copyright 2005 Ron Silliman Papers MSS 0075 1 Descriptive Summary Title: Ron Silliman Papers Identifier/Call Number: MSS 0075 Contributing Institution: Special Collections & Archives, UC San Diego 9500 Gilman Drive La Jolla, California, 92093-0175 Languages: English Physical Description: 10.4 Linear feet(26 archives boxes) Date (inclusive): 1965-1988 Abstract: Papers of Ron Silliman, American writer and editor. Silliman has lived in the San Francisco Bay Area most of his life and is associated with the Language school of contemporary writers. He edited the anthology In The American Tree, published in 1986. The papers include extensive correspondence with many prominent contemporary writers, including Rae Armantrout, Charles Bernstein, Michael Davidson, Lyn Hejinian, Douglas Messerli, John Taggart, and Hanna Weiner. Also included are drafts of Silliman's published works, notebooks, and materials relating to In the American Tree. The collection is divided into five series: 1) ORIGINAL FINDING AID, 2) CORRESPONDENCE, 3) WRITINGS, 4) IN THE AMERICAN TREE and 5) ORIGINALS OF PRESERVATION PHOTOCOPIES. Creator: Silliman, Ronald, 1946- Scope and Content of Collection The Ron Silliman papers contain collected correspondence and writings related to Silliman's career as a writer. The materials cover a range from the mid-1960s to 1988, excluding his most recent publication WHAT (1988). The collection is divided into five series: 1) ORIGINAL FINDING AID, 2) CORRESPONDENCE, 3) WRITINGS, 4) IN THE AMERICAN TREE and 5) ORIGINALS OF PRESERVATION PHOTOCOPIES. -

Essay Partly on the Tolerance Project by Stephen Voyce

TOWARD AN OPEN SOURCE POETICS: APPROPRIATION, COLLABORATION, AND THE COMMONS Author(s): Stephen Voyce Source: Criticism, Vol. 53, No. 3, Open Source (Summer 2011), pp. 407-438 Published by: Wayne State University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23133908 Accessed: 07-12-2017 20:53 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23133908?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Wayne State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Criticism This content downloaded from 165.123.34.86 on Thu, 07 Dec 2017 20:53:50 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms TOWARD AN OPEN SOURCE POETICS: APPROPRIATION, COLLABORATION, AND THE COMMONS Stephen Voyce Intellectual Property is the oil of the 21st century. —Mark Getty, Chairman of Getty Images (2000)' The new artistic paradigm is distribution. —Kenneth Goldsmith, word processor (2002)2 Software programmers first introduced the term open source to describe a model of peer production in which users are free to access, modify, and collaborate on software code.