Avant-Garde Haiku: a New Outlook Philip Rowland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lyn Hejinian “The Inanimate Are Rocks, Desks, Bubble,” 50 from My Life 51 from Writing Is an Aid to Memory 54 the Green 57 “The Erosion of Rocks Blooms

in the american tree Silliman in the american tree Second Edition, with a new Afterword by Ron Silliman The “Language Poets” have extended the Pound-Williams (or perhaps the Pound-Williams- in the americanlanguage tree realism poetry Zukofsky-Stein) tradition in American writing into new and unexpected territories. In the process, these poets have established themselves as the most rigorous and the most radically experi- mental avant-garde on the current literary scene. This anthology offers the most substantial col- lection of work by the Language Poets now available, along with 130 pages of theoretic statements by poets included in the anthology. As such, In the American Tree does for a new generation of American poets what Don Allen’s The New American Poetry did for an earlier generation. The poets represented include Robert Grenier, Barrett Watten, Lyn Hejinian, Bob Perelman, Michael Palmer, Michael Davidson, Clark Coolidge, Charles Bernstein, Hannah Weiner, Bruce Andrews, Susan Howe, Fanny Howe, Bernadette Mayer, Ray DiPalma, and many others. “For millennia, poets have had to make their own way and the world that goes with it. The genius of these various writers and the consummate clartiy with which they are presented here make very clear again that not only is this the road now crucial for all poetry, it’s literally where we are going.” –Robert Creeley “This historic anthology brings into long-needed focus the only serious and concerted movement in American literature of the past two decades. It will be indispensible to anyone with interest in writ- ing’s present and hope for writing’s future.” –Peter Schjeldahl “Provocative in its critique and antidote, this collection invites the curious writer/reader to question all assumptions regarding generally agreed upon values of poetic language practices. -

Ideas, 9 | Printemps / Été 2017 Cultural Imperialism Or Dialogue on Equal Terms? International Publications O

IdeAs Idées d'Amériques 9 | Printemps / Été 2017 Poètes et éditeurs : diffuser la poésie d'avant-garde américaine (depuis 1945) Cultural imperialism or dialogue on equal terms? International publications of innovative American poetry Impérialisme culturel ou dialogue entre égaux ? La publication internationale de la poésie nord-américaine expérimentale ¿Imperialismo cultural o diálogo entre iguales? Publicaciones internacionales de poesía estadounidense innovadora Manuel Brito Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ideas/2054 DOI : 10.4000/ideas.2054 ISSN : 1950-5701 Éditeur Institut des Amériques Référence électronique Manuel Brito, « Cultural imperialism or dialogue on equal terms? International publications of innovative American poetry », IdeAs [En ligne], 9 | Printemps / Été 2017, mis en ligne le 18 juillet 2017, consulté le 21 avril 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ideas/2054 ; DOI : 10.4000/ideas.2054 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 21 avril 2019. IdeAs – Idées d’Amériques est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Cultural imperialism or dialogue on equal terms? International publications o... 1 Cultural imperialism or dialogue on equal terms? International publications of innovative American poetry Impérialisme culturel ou dialogue entre égaux ? La publication internationale de la poésie nord-américaine expérimentale ¿Imperialismo cultural o diálogo entre iguales? Publicaciones internacionales de poesía estadounidense innovadora Manuel Brito Many thanks to the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation for its ongoing support of the Project (FFI 2009 10786) from which this essay comes. I also appreciate the IdeAs reviewers’ recommendations, which have definitely improved this essay. Introduction 1 It is true that the simple question “what is language?” has grounded most of the American poetic avant-garde since 1970. -

LANGUAGE POETRY Entry for the Greenwood Encyclopedia of American Poetry (2005)

Craig Dworkin: LANGUAGE POETRY Entry for The Greenwood Encyclopedia of American Poetry (2005) The discrepancy between the number of people who hold an opinion about Language Poetry and those who have actually read Language Poetry is perhaps greater than for any other literary phenomenon of the later twentieth century. For just one concrete indicator of this gap, a primer on "The Poetry Pantheon" in The New York Times Magazine (19 February, 1995) listed Paul Hoover, Ann Lauterbach, and Leslie Scalapino as the most representative “Language Poets” — a curious choice given that neither Hoover nor Lauterbach appears in any of the defining publications of Language Poetry, and that Scalapino, though certainly associated with Language Poetry, was hardly a central figure. Indeed, only a quarter-century after the phrase was first used, it has often come to serve as an umbrella term for any kind of self-consciously "postmodern" poetry or to mean no more than some vaguely imagined stylistic characteristics — parataxis, dryly apodictic abstractions, elliptical modes of disjunction — even when they appear in works that would actually seem to be fundamentally opposed to the radical poetics that had originally given such notoriety to the name “Language Poetry” in the first place. The term "language poetry" may have first been used by Bruce Andrews, in correspondence from the early 1970s, to distinguish poets such as Vito Hannibal Acconci, Carl Andre, Clark Coolidge, and Jackson Mac Low, whose writing challenged the vatic aspirations of “deep image” poetry. In the tradition of Gertrude Stein and Louis Zukofksy, such poetry found precedents in only the most anomalous contemporary writing, such as John Ashbery's The Tennis Court Oath, Aram Saroyan's Cofee Coffe, Joseph Ceravolo's Fits of Dawn, or Jack Kerouac's Old Angel Midnight. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Patterns of Exchange: Translation, Periodicals and the Poetry Reading in Contemporary French and American Poetry Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2kb1h96x Author Smith, Matthew Bingham Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Patterns of Exchange: Translation, Periodicals and the Poetry Reading in Contemporary French and American Poetry By Matthew Bingham Smith A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in French in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Michael Lucey, Chair Professor Mairi McLaughlin Professor Ann Smock Professor Lyn Hejinian Summer 2015 Abstract Patterns of Exchange: Translation, Periodicals and the Poetry Reading in Contemporary French and American Poetry by Matthew Bingham Smith Doctor of Philosophy in French University of California, Berkeley Professor Michael Lucey, Chair My dissertation offers a transnational perspective on the lively dialogue between French and American poetry since the 1970s. Focusing on the institutions and practices that mediate this exchange, I show how American and French poets take up, challenge or respond to shifts in the poetic field tied to new cross-cultural networks of circulation. In so doing, I also demonstrate how poets imagine and realize a diverse set of competing publics. This work is divided into three chapters. After analyzing in my introduction the web of poets and institutions that have enabled and sustained this exchange, I show in my first chapter how collaborations between writers and translators have greatly impacted recent poetry in a case study of two American works: Andrew Zawack’s Georgia (2009) and Bill Luoma’s My Trip to New York City (1994). -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy sutimitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorged copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9* black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. ProQuest Information and Leaming 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMÏ EIHETORICAL HYBRIDITY: ASHBERY, BERNSTEIN AND THE POETICS OF CITAHON DISSERTATION Presented in. Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy m the Graduate School o f The Ohio State University By \fatthew Richardson^ hlA . ***** The Ohio State Unwersity 2001 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Jon Erickson. Adviser Professor Jessica Prinz . -

Language Writing and the Burden of Critique

Scott Pound Language Writing and the Burden of Critique I HATE SPEECH. —Robert Grenier Robert Grenier’s famous statement has the distinction of being both the principal rallying cry and battle stance of a vigorous avant-garde movement and a deep well of complexity and strangeness. It first appears in a short text called “ON SPEECH,” one of five essays by Grenier published in the first issue of This magazine (1971).1 Fifteen years later, in his introduction to the groundbreaking anthology In the American Tree: Language, Realism, Poetry, Ron Silliman would single out the phrase as the announcement of “a new moment in American writing” (xvii).2 Since then, Silliman and others have returned to Grenier’s statement again and again as the hallmark of a poetics founded on strategies of cultural and critical opposition.3 From this grounding in oppositionalism and critique, language writing has been unified and canonized as a vanguard movement. Looking back now at Silliman’s introduction one is struck by how much qualification it took to stabilize Grenier’s statement. This declaration, Silliman writes, “was not to be taken at face value” (xvii). In fact, “This 1 was obsessed with speech,” in particular Grenier’s own poem “Wintry” which reproduces “dialect variations in prosody and pronunciation of his native Minnesota” (xvii). And Grenier’s “complex call for a projective verse that could . ‘proclaim an abhorrence of ‘speech’”’ was “only one axis of a shift within writing which became manifest with the publication of This” (xvii, emphasis added). Although the “particular contribution of This” was to reject “a speech-based poetics” and consciously raise “the issue of reference,” “neither speech nor reference were ever, in any real sense, ‘the enemy’” (xviii). -

In Early March 1981, Lyn Sent a Letter to Barrett, Bob, Charles Bernstein, Ron, and Steve, Proposing That Each Would Write A

In early March 1981, Lyn sent a letter to Barrett, Bob, Charles Bernstein, Ron, and Steve, proposing that each would write a page on a topic that she named, the whole to serve as an introduction to a selection of Language writings in French translation that would appear in Change magazine, as part of the March 1982 issue focused on “L’espace amérique,” edited (with an additional introduction) by Nanos Valaoritis. In 1989, our same six-person introduction was retranslated into Serbian and published in an issue of Delo, in Yugoslavia. Here is the six-person introduction. Ron Silliman, Barrett Watten, Steve Benson, Lyn Hejinian, Charles Bernstein, Bob Perelman Begun in the sixties, the writing of the American poets gathered here for Change matured into an organized, ongoing literary discourse in the following decade, a period of significant transition for the United States. From the perspective of capital, the war in Indochina was lost, a critical blow to national military prestige. More importantly, 1974 marked the end of capital’s longest “boom,” the expansionist years following the Second World War (on top of which the essential optimism of every variety of “New American” poetry had been constructed). Simultaneously, the largest generation in U.S. history, the “baby boom” of the 40’s and early 50’s, passed from college to the daily practices of material life. Tied to that generation and crippled from the beginning by its rejection of historical knowledge, the American New Left rapidly dissolved, although several of its veterans were to re-emerge as leaders of cross-class movements based on forms of personal oppression, as women or as gays of either sex. -

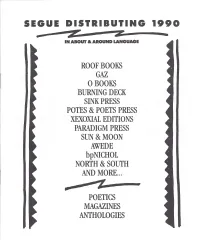

Z: • in ABOUT & AROUND LANGUAGE

F--~~-~- SEGUE DISTRIBUTING 1990 $5 Z z: • IN ABOUT & AROUND LANGUAGE ROOF BOOKS GAZ oBOOKS BURNING DECK SINK PRESS POTES & POETS PRESS XEXOXIAL EDITIONS PARADIGM PRESS SUN &MOON AWEDE bpNICHOL NORTH & SOUTH AND MORE... .......~4__.. $I I- POETICS MAGAZINES ANTHOLOGIES p--------- FEATURED PRESSES ROOF BOOKS Raik by Ray DiPalma The one hundred poems in Ray DiPalma's new collection con The Politics ofPoetic Form: Poetry andPublic Policy tinue his experiments with the poetic line that began in the early Edited by Charles Bernstein 1970s with works such as The Sargasso Transcries, Soli, and Marquee, as well as the long lyric poem Planh. Raik articulates Acollection of 14 essays by contemporary poets and critics that the dynamic variety possible within the fixed form set for each expand on the discussions presented in L=A= N= G= U= poem in the book. A= G= E, focussing on the political and ideological dimensions of the formal and stylistic practices of contemporary poetry. There is a wide range of subject matter to be found here: the lyri These essays were originally presented at the Wolfson Center for cal qualities of Elizabethan underworld slang and the contem National Affairs of the New School for Social Research in New porary urban landscape; meditations on moments in history from York. Each essay is accompanied by an edited transcript of the ancient Egypt and Roman Britain to the Italian Renaissance. discussion that took place at the New School following the initial These choices of subject spotlight DiPalma's assiduous attention presentation. to details. The word choices in each poem stir awareness of each The Politics ofPoetic Form includes full-length essays by Jerome letter in the line. -

Essay Partly on the Tolerance Project by Stephen Voyce

TOWARD AN OPEN SOURCE POETICS: APPROPRIATION, COLLABORATION, AND THE COMMONS Author(s): Stephen Voyce Source: Criticism, Vol. 53, No. 3, Open Source (Summer 2011), pp. 407-438 Published by: Wayne State University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23133908 Accessed: 07-12-2017 20:53 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23133908?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Wayne State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Criticism This content downloaded from 165.123.34.86 on Thu, 07 Dec 2017 20:53:50 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms TOWARD AN OPEN SOURCE POETICS: APPROPRIATION, COLLABORATION, AND THE COMMONS Stephen Voyce Intellectual Property is the oil of the 21st century. —Mark Getty, Chairman of Getty Images (2000)' The new artistic paradigm is distribution. —Kenneth Goldsmith, word processor (2002)2 Software programmers first introduced the term open source to describe a model of peer production in which users are free to access, modify, and collaborate on software code. -

“Too Philosophical for a Poet”: a Conversation with Charles Bernstein

b2 Interview “Too Philosophical for a Poet”: A Conversation with Charles Bernstein Andrew David King ADK: I wanted to start by asking about the phenomenon of the book—as object and as commodity. In 2010, you spoke with Thom Donovan about the process and rationale behind putting together your selected poems, All the Whiskey in Heaven. Certain types of work (nonpoems; this is, of course, a tricky distinction) were excluded: the essays and libretti, for instance, whose presentations alongside poems in My Way unsettle more mainstream, big- publishing- house attitudes toward the compilation of written work. You said that the final product “has a very strong connection from beginning to end,” but that “it’s not in the way that the poems look, or the tone, or the style”: a connection, instead, in the “potentiating recombinations among parts,” which, at the same time, were linearly fused via your decision to exclude book titles from the text proper (making “a kind of text opera”—and there’s your libretto!) from the chronological selections, or, as the case may be, excerpts (Donovan 2010: n.p.). You recently released Recalculating, your first full- length volume of new poems in seven years, and so I wanted to Andrew David King and Charles Bernstein conducted this exchange by email from December 20, 2012, to March 7, 2015. boundary 2 44:3 (2017) DOI 10.1215/01903659- 3898094 © 2017 by Duke University Press Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/boundary-2/article-pdf/44/3/17/498982/BOU44_3_03King_Fpp.pdf by guest on 30 September 2021 18 boundary 2 / August 2017 know if there was anything significantly different for you about the act of putting a collection together now, after curating All the Whiskey in Heaven— or, alternatively, if there’s anything significantly different about the project of assembling a “new” collection versus a selected poems. -

2017-2018 HUMANITIES CENTER BROWN BAG SERIES Poetics As Value Thinking

2017-2018 HUMANITIES CENTER BROWN BAG SERIES Poetics as Value Thinking: The Example of ‘Plan B’ Barrett Watten, Professor, English Wednesday, April 4, 2018 12:30PM-1:30PM Rm. 2339 F/A Bldg This lecture is a hybrid of two thought experiments—one, a discussion of the poetics of value that sees political economy and poetics as twin forms of historically specific making, linked discourses of the determination of value. The second is a proposal for the transvaluation of poetics, and specifically Language and conceptual writing, as prospective organizations of poetic labor as a form of a“knowledge base” (adopted from information and digital theory). The notion that unites both is that poetry and poetics are forms not only of value making but value thinking—sites for the transvaluation of a general notion of value into particular values. Key forebears of the turn to a materialist poetics in modernism—Louis Zukofsky and William Carlos Williams above all—provide examples of poetry as value making in the widest sense. Zukofsky theorized a poetics of value in the making of his keystone work and parallel text, The First Half of “A.” Williams, early and late, shows how the making of the world is what counts as value, nowhere more readable than in the discontinuous unfolding, the uneven development of Paterson. In my second part, I propose how the poetics of Language and conceptual writing can be transvalued, from a static compiling of the data of language toward a transvaluation of the labor congealed in past production—language, poetry, and world. Just as experimental writing was a transvaluation of prior modes of poetry, leading to new values for writing, so the Barrett Watten transvaluation of experimental writing returns it to the world in its form of knowledge base, redefining the task of poetry and poetics as forms of value English thinking. -

AGENEALOGY Into the Company of Love It All Returns

THE LOST AMERICA OF LOVE: A GENEALOGY BARRETT WATTEN, WAYNE STATE UNIVERSITY Into the company of love it all returns. —Robert Creeley1 I This is apocryphal. A party in Hollywood, at which it was known that Liz would appear in the company of Eddie Fisher. Eddie is on the wane. Dick arrives, and while Liz and Dick have not yet consummated their love interest, the tension is electric. Having enjoyed as much of it as anyone can stand, it is time to leave. Liz has the look of one hypnotized, her car keys in her hand. Dick approaches, takes the keys. "You're my girl." "I'm your girl," she repeats, and they go out together. And from that day forward, for as long as it lasts, Eddie is out of the picture.2 Love beckons, and I decide. I want to account for a particular version of "love" in its intersection with poetry as a construction of postmodern American poetics: from its apex among postwar writers grouped together as the New American Poets to its decline and fall with poets of the succeeding generation, After the shipwreck, I managed to salvage only two texts from my extensive library—Sherman Paul's The Lost America of Love and my own Bad History, which I had in any case more or less com- mitted to memory. The Lost America of Love was a book I initially did not like when it was published, but there is nothing like free time on a desert island to reevaluate one's responses. And of course, many memories of my personal association with Paul at the University of Iowa in the early 1970s came back to me on rereading his work.