AGENEALOGY Into the Company of Love It All Returns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Quest Motif in Snyder's the Back Country

LUCI MARÍA COLLIN LA VALLÉ* ? . • THE QUEST MOTIF IN SNYDER'S THE BACK COUNTRY Dissertação apresentada ao Curso de Pós- Graduação em Letras, Área de Concentração em Literaturas de Língua Inglesa, do Setor de Ciências Humanas, Letras e Artes da Universidade Federal ' do Paraná, para a obtenção do grau de Mestre em Letras. Orientador: Profa. Dra. Sigrid Rénaux CURITIBA 1994 f. ] there are some things we have lost, and we should try perhaps to regain them, because I am not sure that in the kind of world in which we are living and with the kind of scientific thinking we are bound to follow, we can regain these things exactly as if they had never been lost; but we can try to become aware of their existence and their importance. C. Lévi-Strauss ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First of all, I would like to acknowledge my American friends Eleanor and Karl Wettlaufer who encouraged my research sending me several books not available here. I am extremely grateful to my sister Mareia, who patiently arranged all the print-outs from the first version to the completion of this work. Thanks are also due to CAPES, for the scholarship which facilitated the development of my studies. Finally, acknowledgment is also given to Dr. Sigrid Rénaux, for her generous commentaries and hëlpful suggestions supervising my research. iii CONTENTS ABSTRACT vi RESUMO vi i OUTLINE OF SNYDER'S LIFE viii 1 INTRODUCTION 01 1.1 Critical Review 04 1.2 Cultural Influences on Snyder's Poetry 12 1.2.1 The Counter cultural Ethos 13 1.2.2 American Writers 20 1.2.3 The Amerindian Tradi tion 33 1.2.4 Oriental Cultures 38 1.3 Conclusion 45 2 INTO THE BACK COUNTRY 56 2.1 Far West 58 2.2 Far East 73 2 .3 Kail 84 2.4 Back 96 3 THE QUEST MOTIF IN THE BACK COUNTRY 110 3.1 The Mythical Approach 110 3.1.1 Literature and Myth 110 3 .1. -

Ideas, 9 | Printemps / Été 2017 Cultural Imperialism Or Dialogue on Equal Terms? International Publications O

IdeAs Idées d'Amériques 9 | Printemps / Été 2017 Poètes et éditeurs : diffuser la poésie d'avant-garde américaine (depuis 1945) Cultural imperialism or dialogue on equal terms? International publications of innovative American poetry Impérialisme culturel ou dialogue entre égaux ? La publication internationale de la poésie nord-américaine expérimentale ¿Imperialismo cultural o diálogo entre iguales? Publicaciones internacionales de poesía estadounidense innovadora Manuel Brito Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ideas/2054 DOI : 10.4000/ideas.2054 ISSN : 1950-5701 Éditeur Institut des Amériques Référence électronique Manuel Brito, « Cultural imperialism or dialogue on equal terms? International publications of innovative American poetry », IdeAs [En ligne], 9 | Printemps / Été 2017, mis en ligne le 18 juillet 2017, consulté le 21 avril 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ideas/2054 ; DOI : 10.4000/ideas.2054 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 21 avril 2019. IdeAs – Idées d’Amériques est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Cultural imperialism or dialogue on equal terms? International publications o... 1 Cultural imperialism or dialogue on equal terms? International publications of innovative American poetry Impérialisme culturel ou dialogue entre égaux ? La publication internationale de la poésie nord-américaine expérimentale ¿Imperialismo cultural o diálogo entre iguales? Publicaciones internacionales de poesía estadounidense innovadora Manuel Brito Many thanks to the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation for its ongoing support of the Project (FFI 2009 10786) from which this essay comes. I also appreciate the IdeAs reviewers’ recommendations, which have definitely improved this essay. Introduction 1 It is true that the simple question “what is language?” has grounded most of the American poetic avant-garde since 1970. -

James S. Jaffe Rare Books Llc

JAMES S. JAFFE RARE BOOKS LLC OCCASIONAL LIST: DECEMBER 2019 P. O. Box 930 Deep River, CT 06417 Tel: 212-988-8042 Email: [email protected] Website: www.jamesjaffe.com Member Antiquarian Booksellers Association of America / International League of Antiquarian Booksellers All items are offered subject to prior sale. Libraries will be billed to suit their budgets. Digital images are available upon request. 1. AGEE, James. The Morning Watch. 8vo, original printed wrappers. Roma: Botteghe Oscure VI, 1950. First (separate) edition of Agee’s autobiographical first novel, printed for private circulation in its entirety. One of an unrecorded number of offprints from Marguerite Caetani’s distinguished literary journal Botteghe Oscure. Presentation copy, inscribed on the front free endpaper: “to Bob Edwards / with warm good wishes / Jim Agee”. The novel was not published until 1951 when Houghton Mifflin brought it out in the United States. A story of adolescent crisis, based on Agee’s experience at the small Episcopal preparatory school in the mountains of Tennessee called St. Andrew’s, one of whose teachers, Father Flye, became Agee’s life-long friend. Wrappers dust-soiled, small area of discoloration on front free-endpaper, otherwise a very good copy, without the glassine dust jacket. Books inscribed by Agee are rare. $2,500.00 2. [ART] BUTLER, Eugenia, et al. The Book of Lies Project. Volumes I, II & III. Quartos, three original portfolios of 81 works of art, (created out of incised & collaged lead, oil paint on vellum, original pencil drawings, a photograph on platinum paper, polaroid photographs, cyanotypes, ashes of love letters, hand- embroidery, and holograph and mechanically reproduced images and texts), with interleaved translucent sheets noting the artist, loose as issued, inserted in a paper chemise and cardboard folder, or in an individual folder and laid into a clamshell box, accompanied by a spiral bound commentary volume in original printed wrappers printed by Carolee Campbell of the Ninja Press. -

An Oral Interpretation Script Illustrating the Influence

379 AN ORAL INTERPRETATION SCRIPT ILLUSTRATING THE INFLUENCE ON CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN POETRY OF THE THREE BLACK MOUNTAIN POETS: CHARLES OLSON, ROBERT CREELEY, ROBERT DUNCAN THESIS Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE By H. Vance James, B.A. Denton, Texas August, 1981 J r James, H. Vance, An Oral Interpretation Script Illustrating the Influence on Contemporary American Poetry of the Three Black Mountain Poets: Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, Robert Duncan. Master of Science (Speech Communication and Drama), August, 1981, 87 pp., bibliography, 23 titles. This oral interpretation thesis analyzes the impact that three poets from Black Mountain College had on contemporary American poetry. The study concentrates on the lives, works, poetic theories of Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, and Robert Duncan and culminates in a lecture recital compiled from historical data relating to Black Mountain College and to the three prominent poets. @ 1981 HAREL VANCE JAMES All Rights Reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS . iv Chapter I. INTRODUCTION . 1 History of Black Mountain College Purpose of the Study Procedure II. BIOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION . 12 Introduction Charles Olson Robert Creeley Robert Duncan III. ANALYSIS . 31 IV. LECTURE RECITAL . 45 The Black Mountain Poets: Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, Robert Duncan "These Days" (Olson) "The Conspiracy" (Creeley) "Come, Let Me Free Myself" (Duncan) "Thank You For Love" (Creeley) "The Door" (Creeley) "Letter 22" (Olson) "The Dance" (Duncan) "The Awakening" (Creeley) "Maximus, To Himself" (Olson) "Words" (Creeley) "Oh No" (Creeley) "The Kingfishers" (Olson) "These Days" (Olson) APPENDIX . -

Poem on the Page: a Collection of Broadsides

Granary Books and Jeff Maser, Bookseller are pleased to announce Poem on the Page: A Collection of Broadsides Robert Creeley. For Benny and Sabina. 15 1/8 x 15 1/8 inches. Photograph by Ann Charters. Portents 18. Portents, 1970. BROADSIDES PROLIFERATED during the small press and mimeograph era as a logical offshoot of poets assuming control of their means of publication. When technology evolved from typewriter, stencil, and mimeo machine to moveable type and sophisticated printing, broadsides provided a site for innovation with design and materials that might not be appropriate for an entire pamphlet or book; thus, they occupy a very specific place within literary and print culture. Poem on the Page: A Collection of Broadsides includes approximately 500 broadsides from a diverse range of poets, printers, designers, and publishers. It is a unique document of a particular aspect of the small press movement as well as a valuable resource for research into the intersection of poetry and printing. See below for a list of some of the poets, writers, printers, typographers, and publishers included in the collection. Selected Highlights from the Collection Lewis MacAdams. A Birthday Greeting. 11 x 17 Antonin Artaud. Indian Culture. 16 x 24 inches. inches. This is no. 90, from an unstated edition, Translated from the French by Clayton Eshleman signed. N.p., n.d. and Bernard Bador with art work by Nancy Spero. This is no. 65 from an edition of 150 numbered and signed by Eshleman and Spero. OtherWind Press, n.d. Lyn Hejinian. The Guard. 9 1/4 x 18 inches. -

Living Into Robert Creeley's Poetics Robert J. Bertholf It

Journal of American Studies of Turkey 27 (2008) : 9-49 And Then He Bought Some Lettuce: Living into Robert Creeley’s Poetics Robert J. Bertholf It must have been the fall semester 1963 when Robert Creeley came to Eugene to give a reading at the University of Oregon. For Love: Poems 1950–1960 had been published the year before. The writing program at the school held generous views about Creeley’s poetry and For Love had already brought in equally generous reviews. I went to the reading with great anticipation, mainly because as a second-year graduate student I was feeling free from Longfellow, Hawthorne and what I thought of as the pernicious New England mind; this was a chance to hear a poet speak directly to an audience and to get a sense of what was being talked about as the “New American Poetry.” The reading began with enthusiasm and went on with the high energy of Creeley’s tightly stretched observations about here and there, the isolation of self and longing for a community, the cry for the commune of love, and the insistence for exploring the abilities of language to express thought. About half way through the reading I was flooded with the terrifying anxiety that Creeley was propounding ways of seeing and thinking that I had fled New England to escape. “This guy’s from New England,” I said to a friend sitting beside me, and left. Creeley’s remark on the subject read years later would not have given me much comfort after leaving the reading: At various times I’ve put emphasis on the fact that I was raised in New England, in Massachusetts for the most part. -

Imc Robert Creeley

^IMC ROBERT CREELEY: A WRITING BIOGRAPHY AND INVENTORY by GERALDINE MARY NOVIK B.A., University of British Columbia, 1966 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of English We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA February, 1973 In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of ENGLISH The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada Date February 7, 1973 ABSTRACT Now, in 1973, it is possible to say that Robert Creeley is a major American poet. The Inventory of works by and about Creeley which comprises more than half of this dissertation documents the publication process that brought him to this stature. The companion Writing Biography establishes Creeley additionally as the key impulse in the new American writing movement that found its first outlet in Origin, Black Mountain Review, Divers Books, Jargon Books, and other alternative little magazines and presses in the fifties. After the second world war a new generation of writers began to define themselves in opposition to the New Criticism and academic poetry then prevalent and in support of Pound and Williams, and as these writers started to appear in tentative little magazines a further definition took place. -

251 Poetry Warrior: Robert Creeley in His Letters

ROBERT ARCHAMBEAU POETRY WARRIOR: ROBERT CREELEY IN HIS LETTERS Creeley, Robert. The Selected Letters of Robert Creeley, ed. Rod Smith, Peter Baker, and Kaplan Harris. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014. Robert Archambeau “The book,” wrote Robert Creeley to Rod Smith, who was then hard at work on the volume in question, Creeley’s Selected Letters, “will certainly ‘tell a story.’” Now that the text of that book has emerged from Smith’s laptop and rests between hard covers, it’s a good time to ask just what story those letters tell. Certainly it isn’t a personal one. Creeley was a New Englander, through and through, and of the silent generation to boot. Yankee reticence blankets the letters too thickly for us to feel much of the texture of Creeley’s quotidian life, beyond whether he feels (to use his favored idiom) he’s “mak- ing it” through the times or not. Instead, the letters, taken together, tell an intensely literary story—and, as the plot develops, an institutional, academic one. Call this story “From the Outside In,” maybe. Or, better, treat it as one of the many Rashomon-like eyewitness accounts of that contentious epic that goes by the title The Poetry Wars. If, like me, you entered the little world of American poetry in the 1990s, you found the Cold War that was ending in the realm of politics to be in full effect in poetry. What had begun as a brushfire conflict between rival journals and anthologies in the fifties and early sixties had settled into an institutionalized rivalry, with an Iron Curtain drawn between the mutu- ally suspicious empires of Iowa City and Buffalo. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy sutimitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorged copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9* black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. ProQuest Information and Leaming 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMÏ EIHETORICAL HYBRIDITY: ASHBERY, BERNSTEIN AND THE POETICS OF CITAHON DISSERTATION Presented in. Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy m the Graduate School o f The Ohio State University By \fatthew Richardson^ hlA . ***** The Ohio State Unwersity 2001 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Jon Erickson. Adviser Professor Jessica Prinz . -

Jonathan Williams, Including Reviews of the Lord of Orchards

Reviews and comments about Jonathan Williams, including reviews of The Lord of Orchards: The Truffle-Hound of American Poetry Jeffery’s official obituary of Jonathan Williams as published in the Asheville Poetry Review, on the North Carolina Arts Council website, and elsewhere, 2008-2010. Jonathan Williams: The Lord of Orchards Indy Week Top Ten Fall Book Releases September 2017. Readings in the Triangle of North Carolina chosen as Our Pick by Indy Week, November 2017. “A not-to-be-missed Festschrift commemorating this witty avant-garde publisher, photographer and man of letters. —Washington Post reviewer Michael Dirda in his holiday 2018 list “Forget trendy bestsellers: This best books list takes you off the beaten track”, November 28, 2018. When I hear the word "bluets," I tend to think not of Maggie Nelson's widely adored lyric essay, but rather of Jonathan Williams. His 1985 book, Blues and Roots/Rue and Bluets: A Garland for the Southern Appalachians, is a paean to the landscape that held and compelled him, a compendium of careful attention to the nuances and the lilt of a place. (Originally from Asheville, Williams, who died in 2008, attended Black Mountain College in the 1950s and lived in Scaly Mountain, N.C., for much of his life.) With Richard Owen, the Hillsborough-based poet Jeffery Beam coedited Jonathan Williams: The Lord of Orchards, a new anthology of "essays, images, and shouts" in response to Williams's fifty-plus years of poetry, photography, Southern folk-art collecting, and publishing (he ran famed independent press The Jargon Society). Fittingly, Beam and Owen bring together a cadre of interdisciplinary artists and writers to celebrate the collection. -

In Early March 1981, Lyn Sent a Letter to Barrett, Bob, Charles Bernstein, Ron, and Steve, Proposing That Each Would Write A

In early March 1981, Lyn sent a letter to Barrett, Bob, Charles Bernstein, Ron, and Steve, proposing that each would write a page on a topic that she named, the whole to serve as an introduction to a selection of Language writings in French translation that would appear in Change magazine, as part of the March 1982 issue focused on “L’espace amérique,” edited (with an additional introduction) by Nanos Valaoritis. In 1989, our same six-person introduction was retranslated into Serbian and published in an issue of Delo, in Yugoslavia. Here is the six-person introduction. Ron Silliman, Barrett Watten, Steve Benson, Lyn Hejinian, Charles Bernstein, Bob Perelman Begun in the sixties, the writing of the American poets gathered here for Change matured into an organized, ongoing literary discourse in the following decade, a period of significant transition for the United States. From the perspective of capital, the war in Indochina was lost, a critical blow to national military prestige. More importantly, 1974 marked the end of capital’s longest “boom,” the expansionist years following the Second World War (on top of which the essential optimism of every variety of “New American” poetry had been constructed). Simultaneously, the largest generation in U.S. history, the “baby boom” of the 40’s and early 50’s, passed from college to the daily practices of material life. Tied to that generation and crippled from the beginning by its rejection of historical knowledge, the American New Left rapidly dissolved, although several of its veterans were to re-emerge as leaders of cross-class movements based on forms of personal oppression, as women or as gays of either sex. -

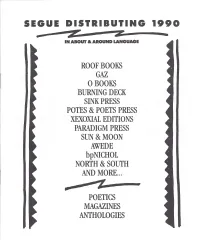

Z: • in ABOUT & AROUND LANGUAGE

F--~~-~- SEGUE DISTRIBUTING 1990 $5 Z z: • IN ABOUT & AROUND LANGUAGE ROOF BOOKS GAZ oBOOKS BURNING DECK SINK PRESS POTES & POETS PRESS XEXOXIAL EDITIONS PARADIGM PRESS SUN &MOON AWEDE bpNICHOL NORTH & SOUTH AND MORE... .......~4__.. $I I- POETICS MAGAZINES ANTHOLOGIES p--------- FEATURED PRESSES ROOF BOOKS Raik by Ray DiPalma The one hundred poems in Ray DiPalma's new collection con The Politics ofPoetic Form: Poetry andPublic Policy tinue his experiments with the poetic line that began in the early Edited by Charles Bernstein 1970s with works such as The Sargasso Transcries, Soli, and Marquee, as well as the long lyric poem Planh. Raik articulates Acollection of 14 essays by contemporary poets and critics that the dynamic variety possible within the fixed form set for each expand on the discussions presented in L=A= N= G= U= poem in the book. A= G= E, focussing on the political and ideological dimensions of the formal and stylistic practices of contemporary poetry. There is a wide range of subject matter to be found here: the lyri These essays were originally presented at the Wolfson Center for cal qualities of Elizabethan underworld slang and the contem National Affairs of the New School for Social Research in New porary urban landscape; meditations on moments in history from York. Each essay is accompanied by an edited transcript of the ancient Egypt and Roman Britain to the Italian Renaissance. discussion that took place at the New School following the initial These choices of subject spotlight DiPalma's assiduous attention presentation. to details. The word choices in each poem stir awareness of each The Politics ofPoetic Form includes full-length essays by Jerome letter in the line.