Hive And/Or the Dark Body of Friendship: a Response to the Grand Piano: an Experiment in Collective Autobiography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ideas, 9 | Printemps / Été 2017 Cultural Imperialism Or Dialogue on Equal Terms? International Publications O

IdeAs Idées d'Amériques 9 | Printemps / Été 2017 Poètes et éditeurs : diffuser la poésie d'avant-garde américaine (depuis 1945) Cultural imperialism or dialogue on equal terms? International publications of innovative American poetry Impérialisme culturel ou dialogue entre égaux ? La publication internationale de la poésie nord-américaine expérimentale ¿Imperialismo cultural o diálogo entre iguales? Publicaciones internacionales de poesía estadounidense innovadora Manuel Brito Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ideas/2054 DOI : 10.4000/ideas.2054 ISSN : 1950-5701 Éditeur Institut des Amériques Référence électronique Manuel Brito, « Cultural imperialism or dialogue on equal terms? International publications of innovative American poetry », IdeAs [En ligne], 9 | Printemps / Été 2017, mis en ligne le 18 juillet 2017, consulté le 21 avril 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ideas/2054 ; DOI : 10.4000/ideas.2054 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 21 avril 2019. IdeAs – Idées d’Amériques est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Cultural imperialism or dialogue on equal terms? International publications o... 1 Cultural imperialism or dialogue on equal terms? International publications of innovative American poetry Impérialisme culturel ou dialogue entre égaux ? La publication internationale de la poésie nord-américaine expérimentale ¿Imperialismo cultural o diálogo entre iguales? Publicaciones internacionales de poesía estadounidense innovadora Manuel Brito Many thanks to the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation for its ongoing support of the Project (FFI 2009 10786) from which this essay comes. I also appreciate the IdeAs reviewers’ recommendations, which have definitely improved this essay. Introduction 1 It is true that the simple question “what is language?” has grounded most of the American poetic avant-garde since 1970. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Patterns of Exchange: Translation, Periodicals and the Poetry Reading in Contemporary French and American Poetry Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2kb1h96x Author Smith, Matthew Bingham Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Patterns of Exchange: Translation, Periodicals and the Poetry Reading in Contemporary French and American Poetry By Matthew Bingham Smith A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in French in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Michael Lucey, Chair Professor Mairi McLaughlin Professor Ann Smock Professor Lyn Hejinian Summer 2015 Abstract Patterns of Exchange: Translation, Periodicals and the Poetry Reading in Contemporary French and American Poetry by Matthew Bingham Smith Doctor of Philosophy in French University of California, Berkeley Professor Michael Lucey, Chair My dissertation offers a transnational perspective on the lively dialogue between French and American poetry since the 1970s. Focusing on the institutions and practices that mediate this exchange, I show how American and French poets take up, challenge or respond to shifts in the poetic field tied to new cross-cultural networks of circulation. In so doing, I also demonstrate how poets imagine and realize a diverse set of competing publics. This work is divided into three chapters. After analyzing in my introduction the web of poets and institutions that have enabled and sustained this exchange, I show in my first chapter how collaborations between writers and translators have greatly impacted recent poetry in a case study of two American works: Andrew Zawack’s Georgia (2009) and Bill Luoma’s My Trip to New York City (1994). -

The Matrix of Poetry: James Schuyler's Diary

Polish Journal for American Studies Yearbook of the Polish Association for American Studies and the Institute of EnglishVol. 11 (Autumn Studie 2017)s, University of Warsaw Vol. 8 (2014) Special Issue Technical Innovation in North American Poetry: Form, Aesthetics, Politics Edited by Kacper Bartczak and Małgorzata Myk AMERICAN STUDIES CENTER UNIVERSITY OF WARSAW INSTITUTE OF ENGLISH STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF WARSAW Polish Journal for American Studies Yearbook of the Polish Association for American Studies Vol. 11 (Autumn 2017) Special Issue Technical Innovation in North American Poetry: Form, Aesthetics, Politics Edited by Kacper Bartczak and Małgorzata Myk Warsaw 2017 MANAGING EDITOR Marek Paryż EDITORIAL BOARD Izabella Kimak, Mirosław Miernik, Jacek Partyka, Paweł Stachura ADVISORY BOARD Andrzej Dakowski, Jerzy Durczak, Joanna Durczak, Andrew S. Gross, Andrea O’Reilly Herrera, Jerzy Kutnik, John R. Leo, Zbigniew Lewicki, Eliud Martínez, Elżbieta Oleksy, Agata Preis-Smith, Tadeusz Rachwał, Agnieszka Salska, Tadeusz Sławek, Marek Wilczyński REVIEWER Paulina Ambroży TYPESETTING AND GRAPHIC DESIGN Miłosz Mierzyński COVER IMAGE Jerzy Durczak, “Bluescape” from the series “New York City.” By permission. https://www.flickr.com/photos/jurek_durczak/ ISSN 1733–9154 Publisher Polish Association for American Studies Al. Niepodległości 22 02–653 Warsaw www.paas.org.pl Nakład: 140 egz. Printed by Sowa – Druk na życzenie phone: +48 22 431 81 40; www.sowadruk.pl Table of Contents Kacper Bartczak and Małgorzata Myk From the Editors ......................................................................................................... 271 Joanna Orska Transition-Translation: Andrzej Sosnowski’s Translation of Three Poems by John Ashbery ......................................................................................................... 275 Mikołaj Wiśniewski The Matrix of Poetry: James Schuyler’s Diary ...................................................... 295 Tadeusz Pióro Autobiography and the Politics and Aesthetics of Language Writing ............... -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy sutimitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorged copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9* black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. ProQuest Information and Leaming 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMÏ EIHETORICAL HYBRIDITY: ASHBERY, BERNSTEIN AND THE POETICS OF CITAHON DISSERTATION Presented in. Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for The Degree Doctor of Philosophy m the Graduate School o f The Ohio State University By \fatthew Richardson^ hlA . ***** The Ohio State Unwersity 2001 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Jon Erickson. Adviser Professor Jessica Prinz . -

Small Press Poetry Collection

Small Press Poetry Collection Alphabetical by press UPDATED MARCH 2019 Numbers 20 Pages 1204. Bernstein, Charles and Susan Bee. The nude formalism. Los Angeles: 20 Pages 1989. 811 Books 998. Corless-Smith, Martin. of the Universe The way things are On the Nature of things The Nature of and being by Lucretius: Incorporating marginalia. [Phoenix, Arizona]: 811 Books [1999] A Aard Press 541. Aaboe, Ruth. Zyzh. London: Aard Press 1978. Abbeygate Books 1339. Cooke, David. On the front. Grimsby: Abbeygate Books 2009. 1340. Cooke, David. Bruegel’s dancers. Grimsby: Abbeygate Books 2009. Acadia Press 484. Adam, Helen. Ballads. Illustrated by Jess. New York: Acadia Press 1964. Active in Airtime 1206. Hawkins, Ralph. Pelt. Brightlingsea, Essex: Active in Airtime 2002. 1219. Hawkins, Ralph. Writ. Colchester: Active in Airtime 1993. Actual Size Press 734. Raworth, Tom. Heavy light. New York: Actual Size Press [1984]. 947. Muckle, John and Ian Davidson. It is now as it was then. London: MICA in association with Actual Size 1983. 1228. De Wit, Johan. Rose poems. [London]: Actual Size 1986. Adam McKeown 1375. Intimacy. Edited by Adam McKeown. Maidstone, Kent: Adam McKeown 1992–1998. Volumes 1–3, 5. Adrian Blamires 1358. Blamires, Adrian. Eliza’s entertainments. [Reading: The Author 2015] Adventures in Poetry 100. O’Hara, Frank. Belgrade, November 19, 1963. New York City: Adventures in Poetry [1972 or 1973] 911. Bernheimer, Alan. The Spoonlight Institute. Princeton NJ: Adventures in Poetry 2009. Afterdays Press 1319. Hullah, Paul and Susan Mowatt. Unquenched. [Edinburgh]: Afterdays Press 2002. Aggie Weston’s 201. Mills, Stuart. ‘There is nothing outside the text’. -

In Early March 1981, Lyn Sent a Letter to Barrett, Bob, Charles Bernstein, Ron, and Steve, Proposing That Each Would Write A

In early March 1981, Lyn sent a letter to Barrett, Bob, Charles Bernstein, Ron, and Steve, proposing that each would write a page on a topic that she named, the whole to serve as an introduction to a selection of Language writings in French translation that would appear in Change magazine, as part of the March 1982 issue focused on “L’espace amérique,” edited (with an additional introduction) by Nanos Valaoritis. In 1989, our same six-person introduction was retranslated into Serbian and published in an issue of Delo, in Yugoslavia. Here is the six-person introduction. Ron Silliman, Barrett Watten, Steve Benson, Lyn Hejinian, Charles Bernstein, Bob Perelman Begun in the sixties, the writing of the American poets gathered here for Change matured into an organized, ongoing literary discourse in the following decade, a period of significant transition for the United States. From the perspective of capital, the war in Indochina was lost, a critical blow to national military prestige. More importantly, 1974 marked the end of capital’s longest “boom,” the expansionist years following the Second World War (on top of which the essential optimism of every variety of “New American” poetry had been constructed). Simultaneously, the largest generation in U.S. history, the “baby boom” of the 40’s and early 50’s, passed from college to the daily practices of material life. Tied to that generation and crippled from the beginning by its rejection of historical knowledge, the American New Left rapidly dissolved, although several of its veterans were to re-emerge as leaders of cross-class movements based on forms of personal oppression, as women or as gays of either sex. -

Winter/Spring 2009

SEGUE READING SERIES These events are made possible, in part, @ BOWERY POETRY CLUB with public funds from The New York State Council on the Arts, a state agency. Saturdays: 4:00 p.m. - 6:00 p.m. 308 BOWERY, just north of Houston ****$6 admission goes to support the readers**** Winter / Spring 2009 The Segue Reading Series is made possible by the support of The Segue Foundation. For more information, please visit seguefoundation.com, bowerypoetry.com, or call (212) 614-0505. Curators: February-March by Nada Gordon & Gary Sullivan, April-May by Kristen Gallagher & Tim Peterson. FEBRUARY FEBRUARY 7 KENNETH GOLDSMITH and EDWIN TORRES Kenneth Goldsmith is the author of ten books of poetry and founding editor of UbuWeb (ubu.com). He is the host of a weekly radio show on New York City’s WFMU and teaches writing at The University of Pennsylvania. A book of critical essays, Uncreative Writing, is forthcoming from Columbia University Press. Edwin Torres is a NYC born lingualisualist currently on hiatus from the apple, living upstate. A NYFA recipient and 2006/7 Lower Manhattan Cultural Council Writer-in-Residence, he’s been widely published and taught his Brainlingo workshop at numerous venues & universities. His books include, The PoPedology Of An Ambient Language (Atelos Books), The All-Union Day Of The Shock Worker (Roof Books), Onomalingua: noise songs and poems (Rattapallax e-book), and Please (Faux Press CD-Rom). FEBRUARY 14 STEVE BENSON and STEPHANIE YOUNG Steve Benson, formerly of the San Francisco Bay area, has lived in Downeast Maine since 1996. Transcripts of orally improvised performanc- es appear in Blindspots (Whale Cloth, 1981), Reverse Order (Potes and Poets, 1989), Blue Book (The Figures/Roof, 1998) and Open Clothes (Atelos, 2005), along with written works. -

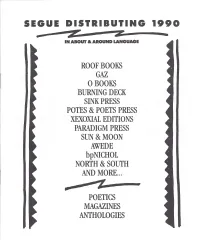

Z: • in ABOUT & AROUND LANGUAGE

F--~~-~- SEGUE DISTRIBUTING 1990 $5 Z z: • IN ABOUT & AROUND LANGUAGE ROOF BOOKS GAZ oBOOKS BURNING DECK SINK PRESS POTES & POETS PRESS XEXOXIAL EDITIONS PARADIGM PRESS SUN &MOON AWEDE bpNICHOL NORTH & SOUTH AND MORE... .......~4__.. $I I- POETICS MAGAZINES ANTHOLOGIES p--------- FEATURED PRESSES ROOF BOOKS Raik by Ray DiPalma The one hundred poems in Ray DiPalma's new collection con The Politics ofPoetic Form: Poetry andPublic Policy tinue his experiments with the poetic line that began in the early Edited by Charles Bernstein 1970s with works such as The Sargasso Transcries, Soli, and Marquee, as well as the long lyric poem Planh. Raik articulates Acollection of 14 essays by contemporary poets and critics that the dynamic variety possible within the fixed form set for each expand on the discussions presented in L=A= N= G= U= poem in the book. A= G= E, focussing on the political and ideological dimensions of the formal and stylistic practices of contemporary poetry. There is a wide range of subject matter to be found here: the lyri These essays were originally presented at the Wolfson Center for cal qualities of Elizabethan underworld slang and the contem National Affairs of the New School for Social Research in New porary urban landscape; meditations on moments in history from York. Each essay is accompanied by an edited transcript of the ancient Egypt and Roman Britain to the Italian Renaissance. discussion that took place at the New School following the initial These choices of subject spotlight DiPalma's assiduous attention presentation. to details. The word choices in each poem stir awareness of each The Politics ofPoetic Form includes full-length essays by Jerome letter in the line. -

Essay Partly on the Tolerance Project by Stephen Voyce

TOWARD AN OPEN SOURCE POETICS: APPROPRIATION, COLLABORATION, AND THE COMMONS Author(s): Stephen Voyce Source: Criticism, Vol. 53, No. 3, Open Source (Summer 2011), pp. 407-438 Published by: Wayne State University Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23133908 Accessed: 07-12-2017 20:53 UTC REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23133908?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms Wayne State University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Criticism This content downloaded from 165.123.34.86 on Thu, 07 Dec 2017 20:53:50 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms TOWARD AN OPEN SOURCE POETICS: APPROPRIATION, COLLABORATION, AND THE COMMONS Stephen Voyce Intellectual Property is the oil of the 21st century. —Mark Getty, Chairman of Getty Images (2000)' The new artistic paradigm is distribution. —Kenneth Goldsmith, word processor (2002)2 Software programmers first introduced the term open source to describe a model of peer production in which users are free to access, modify, and collaborate on software code. -

“Too Philosophical for a Poet”: a Conversation with Charles Bernstein

b2 Interview “Too Philosophical for a Poet”: A Conversation with Charles Bernstein Andrew David King ADK: I wanted to start by asking about the phenomenon of the book—as object and as commodity. In 2010, you spoke with Thom Donovan about the process and rationale behind putting together your selected poems, All the Whiskey in Heaven. Certain types of work (nonpoems; this is, of course, a tricky distinction) were excluded: the essays and libretti, for instance, whose presentations alongside poems in My Way unsettle more mainstream, big- publishing- house attitudes toward the compilation of written work. You said that the final product “has a very strong connection from beginning to end,” but that “it’s not in the way that the poems look, or the tone, or the style”: a connection, instead, in the “potentiating recombinations among parts,” which, at the same time, were linearly fused via your decision to exclude book titles from the text proper (making “a kind of text opera”—and there’s your libretto!) from the chronological selections, or, as the case may be, excerpts (Donovan 2010: n.p.). You recently released Recalculating, your first full- length volume of new poems in seven years, and so I wanted to Andrew David King and Charles Bernstein conducted this exchange by email from December 20, 2012, to March 7, 2015. boundary 2 44:3 (2017) DOI 10.1215/01903659- 3898094 © 2017 by Duke University Press Downloaded from http://read.dukeupress.edu/boundary-2/article-pdf/44/3/17/498982/BOU44_3_03King_Fpp.pdf by guest on 30 September 2021 18 boundary 2 / August 2017 know if there was anything significantly different for you about the act of putting a collection together now, after curating All the Whiskey in Heaven— or, alternatively, if there’s anything significantly different about the project of assembling a “new” collection versus a selected poems. -

2017-2018 HUMANITIES CENTER BROWN BAG SERIES Poetics As Value Thinking

2017-2018 HUMANITIES CENTER BROWN BAG SERIES Poetics as Value Thinking: The Example of ‘Plan B’ Barrett Watten, Professor, English Wednesday, April 4, 2018 12:30PM-1:30PM Rm. 2339 F/A Bldg This lecture is a hybrid of two thought experiments—one, a discussion of the poetics of value that sees political economy and poetics as twin forms of historically specific making, linked discourses of the determination of value. The second is a proposal for the transvaluation of poetics, and specifically Language and conceptual writing, as prospective organizations of poetic labor as a form of a“knowledge base” (adopted from information and digital theory). The notion that unites both is that poetry and poetics are forms not only of value making but value thinking—sites for the transvaluation of a general notion of value into particular values. Key forebears of the turn to a materialist poetics in modernism—Louis Zukofsky and William Carlos Williams above all—provide examples of poetry as value making in the widest sense. Zukofsky theorized a poetics of value in the making of his keystone work and parallel text, The First Half of “A.” Williams, early and late, shows how the making of the world is what counts as value, nowhere more readable than in the discontinuous unfolding, the uneven development of Paterson. In my second part, I propose how the poetics of Language and conceptual writing can be transvalued, from a static compiling of the data of language toward a transvaluation of the labor congealed in past production—language, poetry, and world. Just as experimental writing was a transvaluation of prior modes of poetry, leading to new values for writing, so the Barrett Watten transvaluation of experimental writing returns it to the world in its form of knowledge base, redefining the task of poetry and poetics as forms of value English thinking. -

AGENEALOGY Into the Company of Love It All Returns

THE LOST AMERICA OF LOVE: A GENEALOGY BARRETT WATTEN, WAYNE STATE UNIVERSITY Into the company of love it all returns. —Robert Creeley1 I This is apocryphal. A party in Hollywood, at which it was known that Liz would appear in the company of Eddie Fisher. Eddie is on the wane. Dick arrives, and while Liz and Dick have not yet consummated their love interest, the tension is electric. Having enjoyed as much of it as anyone can stand, it is time to leave. Liz has the look of one hypnotized, her car keys in her hand. Dick approaches, takes the keys. "You're my girl." "I'm your girl," she repeats, and they go out together. And from that day forward, for as long as it lasts, Eddie is out of the picture.2 Love beckons, and I decide. I want to account for a particular version of "love" in its intersection with poetry as a construction of postmodern American poetics: from its apex among postwar writers grouped together as the New American Poets to its decline and fall with poets of the succeeding generation, After the shipwreck, I managed to salvage only two texts from my extensive library—Sherman Paul's The Lost America of Love and my own Bad History, which I had in any case more or less com- mitted to memory. The Lost America of Love was a book I initially did not like when it was published, but there is nothing like free time on a desert island to reevaluate one's responses. And of course, many memories of my personal association with Paul at the University of Iowa in the early 1970s came back to me on rereading his work.