Keith Tuma and Michael Palmer Source: Contemporary Literature, Vol

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jeffreytwitchell-Waas “Poem Beginning 'The'” Has Been Described Aptly As Zu

“O my son Sun”: Poem beginning “The” JeffreyTwitchell-Waas “Poem beginning ‘The’” has been described aptly as Zukofsky’s “calling card” when in 1928 the young, unknown poet submitted it to Ezra Pound for publication in The Exile .1 All things considered, the poem was certainly a personal success, immediately introducing him to a world of relatively established modernist poets and the promise of further publication. Recently the poem has attracted a disproportionate amount of critical attention primarily because it addresses the intersection of and tensions between modernism and Jewishness, as well as having the advantage of appearing more accessible than the rest of Zukofsky’s major poems. However, the common reading of the poem, as centrally concerned with a young Jewish poet who must assert his ethnic identity against prevailing modernist ideologies that would marginalize him, is untenable. 2 It would be more plausible to read the poem as leaving behind such an identity or as explaining why he has already done so: although he certainly does not reject his Jewishness as an inevitable part of his make-up and work, he does reject Jewishness as an identity out of which he consciously writes or that would frame how he is to be read. In “Poem beginning ‘The’” poetic modernism (and to a degree political modernism) offers a way out of this narrower self-definition. A question that has not been asked is why “Poem beginning ‘The’” remains a one- off—there is almost nothing else like it in tone or manner in Zukofsky’s subsequent writing. One consequence is that whatever the intrinsic interest of the poem, it is a poor basis for making generalizations about Zukofsky’s poetry and attitudes. -

Yiddish and the Avant-Garde in American Jewish Poetry Sarah

Yiddish and the Avant-Garde in American Jewish Poetry Sarah Ponichtera Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 ©2012 Sarah Ponichtera All rights reserved All Louis Zukofsky material Copyright Paul Zukofsky; the material may not be reproduced, quoted, or used in any manner whatsoever without the explicit and specific permission of the copyright holder. A fee will be charged. ABSTRACT Yiddish and the Avant-Garde in American Jewish Poetry Sarah Ponichtera This dissertation traces the evolution of a formalist literary strategy through the twentieth century in both Yiddish and English, through literary and historical analyses of poets and poetic groups from the turn of the century until the 1980s. It begins by exploring the ways in which the Yiddish poet Yehoash built on the contemporary interest in the primitive as he developed his aesthetics in the 1900s, then turns to the modernist poetic group In zikh (the Introspectivists) and their efforts to explore primitive states of consciousness in individual subjectivity. In the third chapter, the project turns to Louis Zukofsky's inclusion of Yehoash's Yiddish translations of Japanese poetry in his own English epic, written in dialogue with Ezra Pound. It concludes with an examination of the Language poets of the 1970s, particularly Charles Bernstein's experimental verse, which explores the way that language shapes consciousness through the use of critical and linguistic discourse. Each of these poets or poetic groups uses experimental poetry as a lens through which to peer at the intersections of language and consciousness, and each explicitly identifies Yiddish (whether as symbol or reality) as an essential component of their poetic technique. -

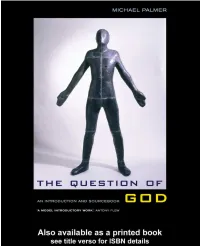

THE QUESTION of GOD: an Introduction and Sourcebook

THE QUESTION OF GOD This important new text by a well-known author provides a lively and approachable introduction to the six great arguments for the existence of God. Requiring no specialist knowledge of philosophy, an important feature of The Question of God is the inclusion of a wealth of primary sources drawn from both classic and contemporary texts. With its combination of critical analysis and extensive extracts, this book will be particularly attractive to students and teachers of philosophy, religious studies and theology, at school or university level, who are looking for a text that offers a detailed and authoritative account of these famous arguments. • The Ontological Argument (sources: Anselm, Haight, Descartes, Kant, Findlay, Malcolm, Hick) • The Cosmological Argument (sources: Aquinas, Taylor, Hume, Kant) • The Argument from Design (sources: Paley, Hume, Darwin, Dawkins, Ward) • The Argument from Miracles (sources: Hume, Hambourger, Coleman, Flew, Swinburne, Diamond) • The Moral Argument (sources: Plato, Lewis, Kant, Rachels, Martin, Nielsen) • The Pragmatic Argument (sources: Pascal, Gracely, Stich, Penelhum, James, Moore). This user-friendly books also offers: • Revision questions to aid comprehension • Key reading for each chapter and an extensive bibliography • Illustrated biographies of key thinkers and their works • Marginal notes and summaries of arguments. Dr Michael Palmer was formerly a Teaching Fellow at McMaster University and Humbodlt Fellow at Marburg University. He has also taught at Marlborough College and Bristol University, and was for many years Head of the Department of Religion and Philosophy at The Manchester Grammar School. A widely read author, his Moral Problems (1991) has already established itself as a core text in schools and colleges. -

Walter Pater — Imagism — Objectivist Verse

22 WALTER PATER — IMAGISM — OBJECTIVIST VERSE Richard Parker (The University of Sussex) Abstract In this paper I make a two-fold argument; first that the Objectivist inheritance from modernism is, in a specific sense, Paterian, and secondly, that this Paterian influence (manifested principally in the form of the Paterian aesthetic moment) is not, as might be assumed, in conflict with the political tendencies exhibited by my central examples—Ezra Pound and Louis Zukofsky—but that the arguably apolitical aesthetic moment is in fact key to their political understandings. I will begin analysing how the Paterian moment lingers in Pound's poetry, especially his Imagist and Vorticist work, and is still at the core of his poetics when he begins The Cantos . I will then go on to argue that this same Paterian aesthetic moment continues in the early work of second-generation Modernists the Objectivists, and will look at the works of Louis as a representative example. I will then argue that this group of poets' Communism is not a break with their engagement with Paterian aestheticism, but that the Paterian moment is in fact alloyed with their understanding of Marxist-Leninism. The engagement with the far left that is generally supposed to mark these writers' defining divide with their modernist forebears will therefore be shown to be more closely linked to the older generation's practices than it might be thought and I will, finally, question the apparently aesthetic basis of Pound's alignment with the far-right. A consensus has developed regarding Walter Pater's influence upon the early stages of literary modernism. -

Introductory Notes

Seth McKelvey, [email protected] Dr. Andrew Zawacki University of Georgia The Skeleton Keyhole: Introductory Notes Introductory Notes I am struck by the depth, complexity, and alternative logics present in many contemporary American experimental poetries, though I am also often turned off by the heavy demands they place on the reader. This so-called “experimental poetry” is in reality a wide group of work which hardly fits under a single umbrella of categorization, but shares in common an unavoidable inaccessibility. Obscurity, marginality, and difficulty are necessary to the works and their significance. Yet I still feel drawn to the populist ideals at the foundation of my own poetics. While I am willing to push through the difficult texts, I find it hard to believe that the average reader is willing to devote such time and effort. Most readers would only ever interact with such exhausting poetry through dissemination by academics. It is paradoxical to attempt to define, group, or canonize contemporary experimental poetry, which is centered around decentralization, on the indefinable, and on rejecting any confinements or limitations that could be placed around it in the name of understanding or explication. As Michael Palmer points out, “as soon as you propose a counter-poetics, it immediately becomes official and therefore it isn’t a counter-poetics anymore. It’s an illusion” (Active Boundaries 237). Yet Palmer and his contemporaries are willing to play along with such an illusion, and continue to treat their counter-poetics as if it was some sort of definable, identifiable theory of poetry. Perhaps because it is only through this limiting, restraining approach to such a poetics that one can begin any study or investigation of such an un- understandable poetics, however tainted or defiled such a study might be. -

Nick Selby I in Talking About Transatlantic Influences In

TNEGOTIATIONSRANSATLANTIC INFLUENCE 1, MARCH 2011 69 TRANSATLANTIC INFLUENCE: SOME PATTERNS IN CONTEMPORARY POETRY Nick Selby I In talking about transatlantic influences in contemporary American poetry, this essay finds itself exploring a double-edged condition. As part of such a double-edged condition, the idea of influence is about power-relations (between texts, between poetics, between nations) and, in the ways that this essay is framing it, the idea of poetic influence across the Atlantic is about senses of possession: possession of, and by, something other. My title promises ‘some patterns in contemporary poetry’. But any patterns that emerge in this essay will be neither as orderly nor as clear-cut as this title might imply. What the essay is seeking to do is to trace some ideas and themes that might develop from a consideration of influence in terms of a transatlantic poetics: the essay’s first half examines the work of two British poets – Ric Caddel and Harriet Tarlo – whose work seems unthinkable without the influence of post-war American poetics upon it; and in its second half the essay thinks through three American poets – Robert Duncan, Michael Palmer and Susan Howe – whose work specifically engages the idea of influence in its debating of issues of the textual, the bodily and the poem’s culpability (and influence) within structures of political power. The idea of influence might be seen to be marked in, I think, three ways in the work of these poets. First, is the idea of direct influence – where one poet acknowledges the influence of another poet upon her / him: an example of which might be Ezra Pound’s petulant acknowledgment of Whitman as a ‘pig-headed father’ (and which is the sort of agonistic view of influence espoused by Harold Bloom in his The Anxiety of Influence);1 or, perhaps, in Michael Palmer’s interest in writing poetry out of his contact with and reading of other poets – Celan, Zanzotto, Dante, Robert Duncan (and many others). -

Effeminizing Louis Zukofsky Louis Zukofsky Şiirleri Ve Şiirin Cinsiyeti

Man Engendered: Effeminizing Louis Zukofsky Louis Zukofsky Şiirleri ve Şiirin Cinsiyeti Dror Abend-David University of Florida, US Abstract This article considers the poetry of Louis Zukofsky, who writes from the margins of American society in the beginning of the twentieth century as he comes from a poor family of Jewish immigrants. The article applies a number of attributes that are associated with Women’s Poetry to Zukofsky’s work. The purpose of the article, however, is not to demonstrate that Zukofsky’s poetry is feminine, but that literary characteristics that are labeled feminine are common to writers of different backgrounds that are forced to create from the margins. Such writers are forced to merge the public and the personal and to deconstruct poetic norms, creating new forms of self-expression that will contain their different identities. Keywords: Zukofsky, Gender, Jewish Culture, Identity, Social Hierarchy. Öz Bu makalede, Yahudi göçmeni fakir bir aileden geldiği için yirminci yüzyılın başlarında Amerikan toplumundan dışlanmış bir yazar olan Louis Zukofsky’nin şiirleri ele alınmıştır. Zukofsky’nin eserleri, “kadın yazını” ile ilişkilendirilerek birçok açıdan incelenmiştir. Ancak makalenin yazılış amacı Zukofsky’nin şiirlerinin kadın şairlerin eserleriyle benzerliklerinin olduğunu göstermek değil, kadın şairlere özgü olarak nitelenen yazın özelliklerinin, aslında toplum dışına itilen tüm yazarlarda görüldüğünü açıklamaktır. Böyle yazarlar, toplumla kendi kişiliklerini harmanlayıp alışılmış şiir yapılarını yıkar, özgün kimliklerini yansıtıp kendilerini ifade edebilecekleri yeni yapılar oluşturur. Anahtar Kelimeler: Zukofsky, Toplumsal Cinsiyet, Yahudi Kültürü, Kimlik, Toplumsal Hiyerarşi. To say that she just ‘happened to be a woman’ is to suggest that gender is irrelevant, that it is immaterial to the production and the reception of poetry. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Patterns of Exchange: Translation, Periodicals and the Poetry Reading in Contemporary French and American Poetry Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2kb1h96x Author Smith, Matthew Bingham Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Patterns of Exchange: Translation, Periodicals and the Poetry Reading in Contemporary French and American Poetry By Matthew Bingham Smith A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in French in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Michael Lucey, Chair Professor Mairi McLaughlin Professor Ann Smock Professor Lyn Hejinian Summer 2015 Abstract Patterns of Exchange: Translation, Periodicals and the Poetry Reading in Contemporary French and American Poetry by Matthew Bingham Smith Doctor of Philosophy in French University of California, Berkeley Professor Michael Lucey, Chair My dissertation offers a transnational perspective on the lively dialogue between French and American poetry since the 1970s. Focusing on the institutions and practices that mediate this exchange, I show how American and French poets take up, challenge or respond to shifts in the poetic field tied to new cross-cultural networks of circulation. In so doing, I also demonstrate how poets imagine and realize a diverse set of competing publics. This work is divided into three chapters. After analyzing in my introduction the web of poets and institutions that have enabled and sustained this exchange, I show in my first chapter how collaborations between writers and translators have greatly impacted recent poetry in a case study of two American works: Andrew Zawack’s Georgia (2009) and Bill Luoma’s My Trip to New York City (1994). -

Keats, Vendler, Adorno, and the Theory of the Avant-Garde Author(S): Robert Kaufman Source: Critical Inquiry, Vol

Negatively Capable Dialectics: Keats, Vendler, Adorno, and the Theory of the Avant-Garde Author(s): Robert Kaufman Source: Critical Inquiry, Vol. 27, No. 2 (Winter, 2001), pp. 354-384 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1344254 . Accessed: 28/03/2011 22:17 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucpress. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Critical Inquiry. http://www.jstor.org Negatively Capable Dialectics: Keats, Vendler, Adorno, and the Theory of the Avant-Garde Robert Kaufman Frankfurt school aesthetics has never quite fallen off the literary-cultural map; yet as with other areas of what currently goes by the name theory, interest in this body of work has known its surges and dormancies. -

September 2006 Updrafts

Chaparral from the updrafts California Federation of Chaparral Poets, Inc. serving California poets for over 65 years Volume 67, No. 6 • September, 2006 President Michael Palmer wins Stevens Award James Shuman, PSJ The Academy of American Poets announced September 5 that Michael Palmer has First Vice President been selected as the recipient of the 2006 Wallace Stevens Award. The $100,000 prize David Lapierre, PCR recognizes outstanding and proven mastery in the art of poetry. Second Vice President The judges for the award were poets Robert Hass, which was short-listed for the Canadian Griffi n Poetry Katharine Wilson, RF Fanny Howe, Susan Stewart, Arthur Sze, and Dean Prize; Codes Appearing: Poems 1979–1988 (2001); Th ird Vice President Young. Robert Hass, on selecting Palmer to receive The Promises of Glass (2000); The Lion Bridge: Se- Dan Saucedo, Tw the award, wrote: Fourth Vice President lected Poems 1972–1995 (1998); At Passages (1996); Michael Palmer is the foremost experimental poet Donna Honeycutt, Ap Sun (1988); First Figure (1984); Notes for Echo Lake of his generation and perhaps of the last several Treasurer (1981); Without Music (1977); The Circular Gates generations. A gorgeous writer who has taken Roberta Bearden, PSJ (1974); and Blake’s Newton (1972). He is also the cues from Wallace Stevens, the Black Mountain Recording Secretary author of a prose work, The Danish Notebook (Avec poets, John Ashbery, contemporary French poets, Lee Collins, Tw Books, 1999). the poetics of Octavio Paz, and from language Corresponding Secretary Palmer’s work, which is both alluringly lyrical and poetries. He is one of the most original craftsmen Dorothy Marshall, Tw intensely avant-garde, has inspired a wide range of at work in English at the present time. -

Roots and Routes Poetics at New College of California

Roots and Routes Poetics at New College of California Edited by Patrick James Dunagan Marina Lazzara Nicholas James Whittington Series in Creative Writing Studies Copyright © 2020 by the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Suite 1200, Wilmington, Malaga, 29006 Delaware 19801 Spain United States Series in Creative Writing Studies Library of Congress Control Number: 2020935054 ISBN: 978-1-62273-800-7 Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. Cover design by Vernon Press. Cover image by Max Kirkeberg, diva.sfsu.edu/collections/kirkeberg/bundles/231645 All individual works herein are used with permission, copyright owned by their authors. Selections from "Basic Elements of Poetry: Lecture Notes from Robert Duncan Class at New College of California," Robert Duncan are © the Jess Collins Trust. -

Louis Zukofsky: Sources of US Modernism Timothy Morgan Cahill University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2009 Louis Zukofsky: sources of US modernism Timothy Morgan Cahill University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Cahill, Timothy Morgan, Louis Zukofsky: sources of US modernism, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Journalism and Creative Writing, Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, 2009. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/3424 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact Manager Repository Services: [email protected]. Title Sheet Louis Zukofsky: Sources of US Modernism A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree Doctor of Philosophy from UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG by Timothy Morgan Cahill, Bachelor of Creative Arts (Honours, 1st Class) Faculty of Creative Arts, School of Journalism and Creative Writing 2009 CERTIFICATION I, Timothy Morgan Cahill, declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Faculty of Creative Arts, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualification at any other academic institution. Timothy Morgan Cahill 25 March 2009 CONTENTS ABSTRACT .......................................................................................................... 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................................