Nick Selby I in Talking About Transatlantic Influences In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

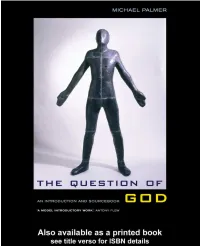

THE QUESTION of GOD: an Introduction and Sourcebook

THE QUESTION OF GOD This important new text by a well-known author provides a lively and approachable introduction to the six great arguments for the existence of God. Requiring no specialist knowledge of philosophy, an important feature of The Question of God is the inclusion of a wealth of primary sources drawn from both classic and contemporary texts. With its combination of critical analysis and extensive extracts, this book will be particularly attractive to students and teachers of philosophy, religious studies and theology, at school or university level, who are looking for a text that offers a detailed and authoritative account of these famous arguments. • The Ontological Argument (sources: Anselm, Haight, Descartes, Kant, Findlay, Malcolm, Hick) • The Cosmological Argument (sources: Aquinas, Taylor, Hume, Kant) • The Argument from Design (sources: Paley, Hume, Darwin, Dawkins, Ward) • The Argument from Miracles (sources: Hume, Hambourger, Coleman, Flew, Swinburne, Diamond) • The Moral Argument (sources: Plato, Lewis, Kant, Rachels, Martin, Nielsen) • The Pragmatic Argument (sources: Pascal, Gracely, Stich, Penelhum, James, Moore). This user-friendly books also offers: • Revision questions to aid comprehension • Key reading for each chapter and an extensive bibliography • Illustrated biographies of key thinkers and their works • Marginal notes and summaries of arguments. Dr Michael Palmer was formerly a Teaching Fellow at McMaster University and Humbodlt Fellow at Marburg University. He has also taught at Marlborough College and Bristol University, and was for many years Head of the Department of Religion and Philosophy at The Manchester Grammar School. A widely read author, his Moral Problems (1991) has already established itself as a core text in schools and colleges. -

Introductory Notes

Seth McKelvey, [email protected] Dr. Andrew Zawacki University of Georgia The Skeleton Keyhole: Introductory Notes Introductory Notes I am struck by the depth, complexity, and alternative logics present in many contemporary American experimental poetries, though I am also often turned off by the heavy demands they place on the reader. This so-called “experimental poetry” is in reality a wide group of work which hardly fits under a single umbrella of categorization, but shares in common an unavoidable inaccessibility. Obscurity, marginality, and difficulty are necessary to the works and their significance. Yet I still feel drawn to the populist ideals at the foundation of my own poetics. While I am willing to push through the difficult texts, I find it hard to believe that the average reader is willing to devote such time and effort. Most readers would only ever interact with such exhausting poetry through dissemination by academics. It is paradoxical to attempt to define, group, or canonize contemporary experimental poetry, which is centered around decentralization, on the indefinable, and on rejecting any confinements or limitations that could be placed around it in the name of understanding or explication. As Michael Palmer points out, “as soon as you propose a counter-poetics, it immediately becomes official and therefore it isn’t a counter-poetics anymore. It’s an illusion” (Active Boundaries 237). Yet Palmer and his contemporaries are willing to play along with such an illusion, and continue to treat their counter-poetics as if it was some sort of definable, identifiable theory of poetry. Perhaps because it is only through this limiting, restraining approach to such a poetics that one can begin any study or investigation of such an un- understandable poetics, however tainted or defiled such a study might be. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Patterns of Exchange: Translation, Periodicals and the Poetry Reading in Contemporary French and American Poetry Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2kb1h96x Author Smith, Matthew Bingham Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Patterns of Exchange: Translation, Periodicals and the Poetry Reading in Contemporary French and American Poetry By Matthew Bingham Smith A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in French in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Michael Lucey, Chair Professor Mairi McLaughlin Professor Ann Smock Professor Lyn Hejinian Summer 2015 Abstract Patterns of Exchange: Translation, Periodicals and the Poetry Reading in Contemporary French and American Poetry by Matthew Bingham Smith Doctor of Philosophy in French University of California, Berkeley Professor Michael Lucey, Chair My dissertation offers a transnational perspective on the lively dialogue between French and American poetry since the 1970s. Focusing on the institutions and practices that mediate this exchange, I show how American and French poets take up, challenge or respond to shifts in the poetic field tied to new cross-cultural networks of circulation. In so doing, I also demonstrate how poets imagine and realize a diverse set of competing publics. This work is divided into three chapters. After analyzing in my introduction the web of poets and institutions that have enabled and sustained this exchange, I show in my first chapter how collaborations between writers and translators have greatly impacted recent poetry in a case study of two American works: Andrew Zawack’s Georgia (2009) and Bill Luoma’s My Trip to New York City (1994). -

Keats, Vendler, Adorno, and the Theory of the Avant-Garde Author(S): Robert Kaufman Source: Critical Inquiry, Vol

Negatively Capable Dialectics: Keats, Vendler, Adorno, and the Theory of the Avant-Garde Author(s): Robert Kaufman Source: Critical Inquiry, Vol. 27, No. 2 (Winter, 2001), pp. 354-384 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1344254 . Accessed: 28/03/2011 22:17 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucpress. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Critical Inquiry. http://www.jstor.org Negatively Capable Dialectics: Keats, Vendler, Adorno, and the Theory of the Avant-Garde Robert Kaufman Frankfurt school aesthetics has never quite fallen off the literary-cultural map; yet as with other areas of what currently goes by the name theory, interest in this body of work has known its surges and dormancies. -

September 2006 Updrafts

Chaparral from the updrafts California Federation of Chaparral Poets, Inc. serving California poets for over 65 years Volume 67, No. 6 • September, 2006 President Michael Palmer wins Stevens Award James Shuman, PSJ The Academy of American Poets announced September 5 that Michael Palmer has First Vice President been selected as the recipient of the 2006 Wallace Stevens Award. The $100,000 prize David Lapierre, PCR recognizes outstanding and proven mastery in the art of poetry. Second Vice President The judges for the award were poets Robert Hass, which was short-listed for the Canadian Griffi n Poetry Katharine Wilson, RF Fanny Howe, Susan Stewart, Arthur Sze, and Dean Prize; Codes Appearing: Poems 1979–1988 (2001); Th ird Vice President Young. Robert Hass, on selecting Palmer to receive The Promises of Glass (2000); The Lion Bridge: Se- Dan Saucedo, Tw the award, wrote: Fourth Vice President lected Poems 1972–1995 (1998); At Passages (1996); Michael Palmer is the foremost experimental poet Donna Honeycutt, Ap Sun (1988); First Figure (1984); Notes for Echo Lake of his generation and perhaps of the last several Treasurer (1981); Without Music (1977); The Circular Gates generations. A gorgeous writer who has taken Roberta Bearden, PSJ (1974); and Blake’s Newton (1972). He is also the cues from Wallace Stevens, the Black Mountain Recording Secretary author of a prose work, The Danish Notebook (Avec poets, John Ashbery, contemporary French poets, Lee Collins, Tw Books, 1999). the poetics of Octavio Paz, and from language Corresponding Secretary Palmer’s work, which is both alluringly lyrical and poetries. He is one of the most original craftsmen Dorothy Marshall, Tw intensely avant-garde, has inspired a wide range of at work in English at the present time. -

Roots and Routes Poetics at New College of California

Roots and Routes Poetics at New College of California Edited by Patrick James Dunagan Marina Lazzara Nicholas James Whittington Series in Creative Writing Studies Copyright © 2020 by the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Suite 1200, Wilmington, Malaga, 29006 Delaware 19801 Spain United States Series in Creative Writing Studies Library of Congress Control Number: 2020935054 ISBN: 978-1-62273-800-7 Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. Cover design by Vernon Press. Cover image by Max Kirkeberg, diva.sfsu.edu/collections/kirkeberg/bundles/231645 All individual works herein are used with permission, copyright owned by their authors. Selections from "Basic Elements of Poetry: Lecture Notes from Robert Duncan Class at New College of California," Robert Duncan are © the Jess Collins Trust. -

The “Objectivists”: a Website Dedicated to the “Objectivist” Poets by Steel Wagstaff a Dissertation Submitted in Partial

The “Objectivists”: A Website Dedicated to the “Objectivist” Poets By Steel Wagstaff A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (English) at the UNIVERSITY OF WISCONSIN‐MADISON 2018 Date of final oral examination: 5/4/2018 The dissertation is approved by the following members of the Final Oral Committee: Lynn Keller, Professor, English Tim Yu, Associate Professor, English Mark Vareschi, Assistant Professor, English David Pavelich, Director of Special Collections, UW-Madison Libraries © Copyright by Steel Wagstaff 2018 Original portions of this project licensed under a CC BY-SA 4.0 license. All Louis Zukofsky materials copyright © Musical Observations, Inc. Used by permission. i TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ..................................................................................... vi Abstract ................................................................................................... vii Introduction ............................................................................................... 1 The Lives ................................................................................................ 31 Who were the “Objectivists”? .............................................................................................................................. 31 Core “Objectivists” .............................................................................................................................................. 31 The Formation of the “Objectivist” -

Curriculum Vitae Yerra Sugarman

SUGARMAN / 1 YERRA SUGARMAN, PH.D. Visiting Assistant Professor University of Toledo Dept. of English Language and Literature Mailstop 126 / 2801 West Bancroft St. Toledo, Ohio 43606 [email protected] Website: https://yerrasugarman.com/ ______________________________________________________________________________ EDUCATION Ph.D. University of Houston, Houston, TX Creative Writing and Literature (Poetry), December 2016 Dissertation: Spirit and Particle. A Book of Poems with a Critical Afterword Entitled “The Poetry of Grief as Resistance” Dissertation Committee: Kevin Prufer, Director; Tony Hoagland; David Mikics; Martha Serpas; Grace Schulman, External Reader Comprehensive Examination Areas: The History of Poetry and Poetics (From the Psalms to the Twentieth Century) The English Renaissance: Poetry, Drama, and a Special Focus on the Seventeenth-Century Devotional Lyric The Elegy in English from the Seventeenth Century to the Twenty-First Century M.A. The City College of The City University of New York Creative Writing (Poetry) Thesis: The Bag of Broken Glass. A Book of Poems Thesis Director: Marilyn Hacker; Second Reader: Jane Marcus M.F.A. Columbia University in the City of New York Visual Arts (With an Emphasis on Painting; Additional Focus on Critical Writing) B.F.A. Concordia University, Montreal, Quebec Visual Arts (magna cum laude) ______________________________________________________________________________ UNIVERSITY POSITIONS (Selected) 2018-Pressent Visiting Assistant Professor of Creative Writing (Full-Time), University -

Surrealist Poetics in Contemporary American Poetry

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA Surrealist Poetics in Contemporary American Poetry A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of English School of Arts & Sciences Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree Doctor of Philosophy By Brooks B. Lampe Washington, D.C. 2014 Surrealist Poetics in Contemporary American Poetry Brooks B. Lampe, Ph.D. Director: Ernest Suarez, Ph.D. The surrealist movement, begun in the 1920s and developed and articulated most visibly and forcefully by André Breton, has unequivocally changed American poetry, yet the nature and history of its impact until recently has not been thoroughly and consistently recounted. The panoramic range of its influence has been implicitly understood but difficult to identify partly because of the ambivalence with which it has been received by American writers and audiences. Surrealism’s call to a “systematic derangement of all the senses” has rarely existed comfortably alongside other modern poetic approaches. Nevertheless, some poets have successfully negotiated this tension and extended surrealism to the context of postmodern American culture. A critical history of surrealism’s influence on American poetry is quickly gaining momentum through the work of scholars, including Andrew Joron, Michael Skau, Charles Borkuis, David Arnold and Garrett Caples. This dissertation joins these scholars by investigating how selected American poets and poetic schools received, transformed, and transmitted surrealism in the second half of the twentieth century, especially during the mid-‘50s through the early ‘80s, when the movement’s influence in the States was rapid and most definitive. First, I summarize the impact of the surrealist movement on American poets through World War II, including Charles Henri Ford, Ezra Pound, William Carlos Williams, and Philip Lamantia, and briefly examine Julian Levy’s anthology, Surrealism (1936). -

Niedecker and the Correspondence with Zukofsky, 1931-1970

Niedecker and the Correspondence with Zukofsky 1931-1970, Jenny Penberthy; Cambridge University Press, 1993. This is a list of books mentioned by Lorine Niedecker in her letters. The review is of Selected Letters of Lorine Niedecker to Louis Zukofsky starting on page 123. Pg. 123; letter #1, dated 1937? Mention of a book on the songs of birds which came with 2 small victrola records. No reference to specific book. Pg. 124; letter #2, dated July 14, 1938 Anton Reiser, Albert Einstein: A Biographical Portrait. Translated anonymously by Louis Zukofsky (New York: Albert & Charles Boni, 1930). Pg. 125; letter # 4, dated May 18, 1941 The Federal Writers Project, Wisconsin: A Guide to the Badger State (New York: Duell, Sloan & Pearce, 1941). Pg. 126; letter #4 Angie Kumlien Main, Yellow-Headed Blackbirds at Lake Koshkonong and Vicinity, reprinted from Transactions of Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts and Letters(January, 1923). Angie Kumlien Main, Thure Kumlien of Koshkonong, Naturalist. The Descendants of Thure and Christine Kumlien, reprinted from the Wisconsin Magazine of History (March, 1944). Pg. 128; letter # 4 Black Hawk, J.B. Patterson, Editor, The Life of Black Hawk (Boston, 1934). Pg. 129; letter # 4 Louis Zukofsky, ‘History of Design’ see Terrell, Carroll, ed. Louis Zukofsky: Man and Poet (Orono Maine: National Poetry Foundation, 1980). Pg. 130; letter # 5 dated Labor Day, 1944 Mentions the manuscripts of: Lorine Niedecker, New Goose and Louis Zukofsky, Anew. She typed both manuscripts which were both published in 1946 by The James Decker Press, Prairie City, Illinois. Pg. 132; letter # 7 dated April 25, 1945 Saturday Review of Literature (a magazine) read reviews of August Derleth, The Edge of Night (The Press of James Decker, 1945) & review of Ruth Lechlitner, Only the Years (The Press of James Decker, 1944). -

Lorine Niedecker 2016 Collection Hoard Historical Museum Fort

Lorine Niedecker 2016 Collection Hoard Historical Museum Fort Atkinson, Wisconsin This collection is from Lorine Niedecker’s personal library, brought to the museum shortly after her death by her husband Albert Millen. The materials were borrowed and returned to the museum in 2016. COLLECTION NOTES - Ann Engelman, Friends of Lorine Niedecker, January 2017 I was honored to catalogue the contents of this box. (2x2’ cardboard) I believe these materials to be from Lorine Niedecker’s library, donated to the museum by her husband Albert Millen shortly after Lorine’s death, per Merrilee Lee, Director, Hoard Historical Museum. Loaned out, the materials were returned in 2017. Notes on the Master List, made specifically by me are indicated “ae.” I was careful about assumptions - what was in Lorine’s hand or someone else’s and noted these. Margot Peters and Karl Gartung also assisted. The two Nidecker My Friend Tree chapbooks were clearly mailed to the researcher who returned these materials and the Niedecker T&G book has his name in it. The assumption is that these did not belong to Lorine but were added, gratefully, to the box contents on return. There were also 3x5 cards that have handwriting that is not Lorine’s. There may be other instances and notes were made accordingly. All contents were very dusty. Damaged conditions, minimal, were noted. I was surprised and delighted how many chap books and books were inscribed to Lorine by their authors. Jargon Press was well represented. The number and variety of small press publishers is impressive. There are many chap books and books by Louis Zukofsky, Jonathans Williams, Ian Hamilton Finley and others. -

Keith Tuma and Michael Palmer Source: Contemporary Literature, Vol

An Interview with Michael Palmer Author(s): Keith Tuma and Michael Palmer Source: Contemporary Literature, Vol. 30, No. 1 (Spring, 1989), pp. 1-12 Published by: University of Wisconsin Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1208421 Accessed: 03/10/2008 00:18 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=uwisc. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of Wisconsin Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Contemporary Literature. http://www.jstor.org MichaelPalmer. Photo OThomasVictor. AN INTERVIEW WITH MICHAEL PALMER Conductedby Keith Tuma MichaelPalmer was born in New YorkCity in 1943 and educatedat Harvard,where he receivedan M.A.