Introductory Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Addison Street Poetry Walk

THE ADDISON STREET ANTHOLOGY BERKELEY'S POETRY WALK EDITED BY ROBERT HASS AND JESSICA FISHER HEYDAY BOOKS BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA CONTENTS Acknowledgments xi Introduction I NORTH SIDE of ADDISON STREET, from SHATTUCK to MILVIA Untitled, Ohlone song 18 Untitled, Yana song 20 Untitied, anonymous Chinese immigrant 22 Copa de oro (The California Poppy), Ina Coolbrith 24 Triolet, Jack London 26 The Black Vulture, George Sterling 28 Carmel Point, Robinson Jeffers 30 Lovers, Witter Bynner 32 Drinking Alone with the Moon, Li Po, translated by Witter Bynner and Kiang Kang-hu 34 Time Out, Genevieve Taggard 36 Moment, Hildegarde Flanner 38 Andree Rexroth, Kenneth Rexroth 40 Summer, the Sacramento, Muriel Rukeyser 42 Reason, Josephine Miles 44 There Are Many Pathways to the Garden, Philip Lamantia 46 Winter Ploughing, William Everson 48 The Structure of Rime II, Robert Duncan 50 A Textbook of Poetry, 21, Jack Spicer 52 Cups #5, Robin Blaser 54 Pre-Teen Trot, Helen Adam , 56 A Strange New Cottage in Berkeley, Allen Ginsberg 58 The Plum Blossom Poem, Gary Snyder 60 Song, Michael McClure 62 Parachutes, My Love, Could Carry Us Higher, Barbara Guest 64 from Cold Mountain Poems, Han Shan, translated by Gary Snyder 66 Untitled, Larry Eigner 68 from Notebook, Denise Levertov 70 Untitied, Osip Mandelstam, translated by Robert Tracy 72 Dying In, Peter Dale Scott 74 The Night Piece, Thorn Gunn 76 from The Tempest, William Shakespeare 78 Prologue to Epicoene, Ben Jonson 80 from Our Town, Thornton Wilder 82 Epilogue to The Good Woman of Szechwan, Bertolt Brecht, translated by Eric Bentley 84 from For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide I When the Rainbow Is Enuf, Ntozake Shange 86 from Hydriotaphia, Tony Kushner 88 Spring Harvest of Snow Peas, Maxine Hong Kingston 90 Untitled, Sappho, translated by Jim Powell 92 The Child on the Shore, Ursula K. -

Jack Spicer Papers, 1939-1982, Bulk 1943-1965

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt9199r33h No online items Finding Aid to the Jack Spicer Papers, 1939-1982, bulk 1943-1965 Finding Aid written by Kevin Killian The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California, 94720-6000 Phone: (510) 642-6481 Fax: (510) 642-7589 Email: [email protected] URL: http://bancroft.berkeley.edu/ © 2007 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Finding Aid to the Jack Spicer BANC MSS 2004/209 1 Papers, 1939-1982, bulk 1943-1965 Finding Aid to the Jack Spicer Papers, 1939-1982, bulk 1943-1965 Collection Number: BANC MSS 2004/209 The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California Finding Aid Written By: Kevin Killian Date Completed: February 2007 © 2007 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Collection Title: Jack Spicer papers Date (inclusive): 1939-1982, Date (bulk): bulk 1943-1965 Collection Number: BANC MSS 2004/209 Creator : Spicer, Jack Extent: Number of containers: 32 boxes, 1 oversize boxLinear feet: 12.8 linear ft. Repository: The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California 94720-6000 Abstract: The Jack Spicer Papers, 1939-1982, document Spicer's career as a poet in the San Francisco Bay Area. Included are writings, correspondence, teaching materials, school work, personal papers, and materials relating to the literary magazine J. Spicer's creative works constitute the bulk of the collection and include poetry, plays, essays, short stories, and a novel. Correspondence is also significant, and includes both outgoing and incoming letters to writers such as Robin Blaser, Harold and Dora Dull, Robert Duncan, Lewis Ellingham, Landis Everson, Fran Herndon, Graham Mackintosh, and John Allan Ryan, among others. -

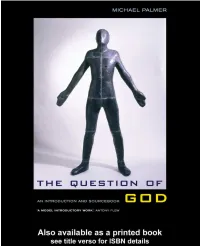

THE QUESTION of GOD: an Introduction and Sourcebook

THE QUESTION OF GOD This important new text by a well-known author provides a lively and approachable introduction to the six great arguments for the existence of God. Requiring no specialist knowledge of philosophy, an important feature of The Question of God is the inclusion of a wealth of primary sources drawn from both classic and contemporary texts. With its combination of critical analysis and extensive extracts, this book will be particularly attractive to students and teachers of philosophy, religious studies and theology, at school or university level, who are looking for a text that offers a detailed and authoritative account of these famous arguments. • The Ontological Argument (sources: Anselm, Haight, Descartes, Kant, Findlay, Malcolm, Hick) • The Cosmological Argument (sources: Aquinas, Taylor, Hume, Kant) • The Argument from Design (sources: Paley, Hume, Darwin, Dawkins, Ward) • The Argument from Miracles (sources: Hume, Hambourger, Coleman, Flew, Swinburne, Diamond) • The Moral Argument (sources: Plato, Lewis, Kant, Rachels, Martin, Nielsen) • The Pragmatic Argument (sources: Pascal, Gracely, Stich, Penelhum, James, Moore). This user-friendly books also offers: • Revision questions to aid comprehension • Key reading for each chapter and an extensive bibliography • Illustrated biographies of key thinkers and their works • Marginal notes and summaries of arguments. Dr Michael Palmer was formerly a Teaching Fellow at McMaster University and Humbodlt Fellow at Marburg University. He has also taught at Marlborough College and Bristol University, and was for many years Head of the Department of Religion and Philosophy at The Manchester Grammar School. A widely read author, his Moral Problems (1991) has already established itself as a core text in schools and colleges. -

Poem on the Page: a Collection of Broadsides

Granary Books and Jeff Maser, Bookseller are pleased to announce Poem on the Page: A Collection of Broadsides Robert Creeley. For Benny and Sabina. 15 1/8 x 15 1/8 inches. Photograph by Ann Charters. Portents 18. Portents, 1970. BROADSIDES PROLIFERATED during the small press and mimeograph era as a logical offshoot of poets assuming control of their means of publication. When technology evolved from typewriter, stencil, and mimeo machine to moveable type and sophisticated printing, broadsides provided a site for innovation with design and materials that might not be appropriate for an entire pamphlet or book; thus, they occupy a very specific place within literary and print culture. Poem on the Page: A Collection of Broadsides includes approximately 500 broadsides from a diverse range of poets, printers, designers, and publishers. It is a unique document of a particular aspect of the small press movement as well as a valuable resource for research into the intersection of poetry and printing. See below for a list of some of the poets, writers, printers, typographers, and publishers included in the collection. Selected Highlights from the Collection Lewis MacAdams. A Birthday Greeting. 11 x 17 Antonin Artaud. Indian Culture. 16 x 24 inches. inches. This is no. 90, from an unstated edition, Translated from the French by Clayton Eshleman signed. N.p., n.d. and Bernard Bador with art work by Nancy Spero. This is no. 65 from an edition of 150 numbered and signed by Eshleman and Spero. OtherWind Press, n.d. Lyn Hejinian. The Guard. 9 1/4 x 18 inches. -

Nick Selby I in Talking About Transatlantic Influences In

TNEGOTIATIONSRANSATLANTIC INFLUENCE 1, MARCH 2011 69 TRANSATLANTIC INFLUENCE: SOME PATTERNS IN CONTEMPORARY POETRY Nick Selby I In talking about transatlantic influences in contemporary American poetry, this essay finds itself exploring a double-edged condition. As part of such a double-edged condition, the idea of influence is about power-relations (between texts, between poetics, between nations) and, in the ways that this essay is framing it, the idea of poetic influence across the Atlantic is about senses of possession: possession of, and by, something other. My title promises ‘some patterns in contemporary poetry’. But any patterns that emerge in this essay will be neither as orderly nor as clear-cut as this title might imply. What the essay is seeking to do is to trace some ideas and themes that might develop from a consideration of influence in terms of a transatlantic poetics: the essay’s first half examines the work of two British poets – Ric Caddel and Harriet Tarlo – whose work seems unthinkable without the influence of post-war American poetics upon it; and in its second half the essay thinks through three American poets – Robert Duncan, Michael Palmer and Susan Howe – whose work specifically engages the idea of influence in its debating of issues of the textual, the bodily and the poem’s culpability (and influence) within structures of political power. The idea of influence might be seen to be marked in, I think, three ways in the work of these poets. First, is the idea of direct influence – where one poet acknowledges the influence of another poet upon her / him: an example of which might be Ezra Pound’s petulant acknowledgment of Whitman as a ‘pig-headed father’ (and which is the sort of agonistic view of influence espoused by Harold Bloom in his The Anxiety of Influence);1 or, perhaps, in Michael Palmer’s interest in writing poetry out of his contact with and reading of other poets – Celan, Zanzotto, Dante, Robert Duncan (and many others). -

View Prospectus

Archive from “A Secret Location” Small Press / Mimeograph Revolution, 1940s–1970s We are pleased to offer for sale a captivating and important research collection of little magazines and other printed materials that represent, chronicle, and document the proliferation of avant-garde, underground small press publications from the forties to the seventies. The starting point for this collection, “A Secret Location on the Lower East Side,” is the acclaimed New York Public Library exhibition and catalog from 1998, curated by Steve Clay and Rodney Phillips, which documented a period of intense innovation and experimentation in American writing and literary publishing by exploring the small press and mimeograph revolutions. The present collection came into being after the owner “became obsessed with the secretive nature of the works contained in the exhibition’s catalog.” Using the book as a guide, he assembled a singular library that contains many of the rare and fragile little magazines featured in the NYPL exhibition while adding important ancillary material, much of it from a West Coast perspective. Left to right: Bill Margolis, Eileen Kaufman, Bob Kaufman, and unidentified man printing the first issue of Beatitude. [Ref SL p. 81]. George Herms letter ca. late 90s relating to collecting and archiving magazines and documents from the period of the Mimeograph Revolution. Small press publications from the forties through the seventies have increasingly captured the interest of scholars, archivists, curators, poets and collectors over the past two decades. They provide bedrock primary source information for research, analysis, and exhibition and reveal little known aspects of recent cultural activity. The Archive from “A Secret Location” was collected by a reclusive New Jersey inventor and offers a rare glimpse into the diversity of poetic doings and material production that is the Small Press Revolution. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Patterns of Exchange: Translation, Periodicals and the Poetry Reading in Contemporary French and American Poetry Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2kb1h96x Author Smith, Matthew Bingham Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Patterns of Exchange: Translation, Periodicals and the Poetry Reading in Contemporary French and American Poetry By Matthew Bingham Smith A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in French in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Michael Lucey, Chair Professor Mairi McLaughlin Professor Ann Smock Professor Lyn Hejinian Summer 2015 Abstract Patterns of Exchange: Translation, Periodicals and the Poetry Reading in Contemporary French and American Poetry by Matthew Bingham Smith Doctor of Philosophy in French University of California, Berkeley Professor Michael Lucey, Chair My dissertation offers a transnational perspective on the lively dialogue between French and American poetry since the 1970s. Focusing on the institutions and practices that mediate this exchange, I show how American and French poets take up, challenge or respond to shifts in the poetic field tied to new cross-cultural networks of circulation. In so doing, I also demonstrate how poets imagine and realize a diverse set of competing publics. This work is divided into three chapters. After analyzing in my introduction the web of poets and institutions that have enabled and sustained this exchange, I show in my first chapter how collaborations between writers and translators have greatly impacted recent poetry in a case study of two American works: Andrew Zawack’s Georgia (2009) and Bill Luoma’s My Trip to New York City (1994). -

Keats, Vendler, Adorno, and the Theory of the Avant-Garde Author(S): Robert Kaufman Source: Critical Inquiry, Vol

Negatively Capable Dialectics: Keats, Vendler, Adorno, and the Theory of the Avant-Garde Author(s): Robert Kaufman Source: Critical Inquiry, Vol. 27, No. 2 (Winter, 2001), pp. 354-384 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1344254 . Accessed: 28/03/2011 22:17 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucpress. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Critical Inquiry. http://www.jstor.org Negatively Capable Dialectics: Keats, Vendler, Adorno, and the Theory of the Avant-Garde Robert Kaufman Frankfurt school aesthetics has never quite fallen off the literary-cultural map; yet as with other areas of what currently goes by the name theory, interest in this body of work has known its surges and dormancies. -

An Education in Space by Paul Hoover Selected Poems Barbara

An Education in Space by Paul Hoover Selected Poems Barbara Guest Sun & Moon Press, 1995 (Originally published in Chicago Tribune Books, November 26, 1995) Born in North Carolina in 1920, Barbara Guest settled in New York City following her graduation from University of California at Berkeley. Soon thereafter, she came into contact with James Schuyler, Frank O'Hara, John Ashbery, and Kenneth Koch, who, with Guest, would later emerge as the New York School poets. Influenced by Abstract Expressionism, Surrealism, and in general French experiment since Rimbaud and Mallarmé, the group would bring wit and charm to American poetry, as well as an extraordinary visual sense. Guest was somewhat belatedly discovered as a major figure of the group. In part, this has to do with her marginalized position as a woman. But it is also due to a ten-year hiatus in her production, from the long poem The Türler Losses (1979) to her breakthrough collection Fair Realism (1989). In the intervening period, Guest produced Herself Defined (1984), an acclaimed biography of the poet H.D. Ironically, it was a younger generation to follow the New York School, the language poets, who would give her work its new status. Given their attraction to what poet Charles Bernstein calls “mis-seaming,” a style in which the seams or transitions have as much weight as the poetic fabric, it’s surprising that the language poets would so value Guest’s often lyrical and metaphysical poetry. In her poem ‘The Türler Losses,’ for instance, “Loss gropes toward its vase. Etching the way. / Driving horses around the Etruscan rim.” In an earlier work, ‘Prairie Houses,’ Guest wrote of the prairie, “Regard its hard-mouthed houses with their / robust nipples the gossamer hair,” lines which have their visual equivalent in the Surrealist paintings of Paul Delvaux and Rene Magritte. -

September 2006 Updrafts

Chaparral from the updrafts California Federation of Chaparral Poets, Inc. serving California poets for over 65 years Volume 67, No. 6 • September, 2006 President Michael Palmer wins Stevens Award James Shuman, PSJ The Academy of American Poets announced September 5 that Michael Palmer has First Vice President been selected as the recipient of the 2006 Wallace Stevens Award. The $100,000 prize David Lapierre, PCR recognizes outstanding and proven mastery in the art of poetry. Second Vice President The judges for the award were poets Robert Hass, which was short-listed for the Canadian Griffi n Poetry Katharine Wilson, RF Fanny Howe, Susan Stewart, Arthur Sze, and Dean Prize; Codes Appearing: Poems 1979–1988 (2001); Th ird Vice President Young. Robert Hass, on selecting Palmer to receive The Promises of Glass (2000); The Lion Bridge: Se- Dan Saucedo, Tw the award, wrote: Fourth Vice President lected Poems 1972–1995 (1998); At Passages (1996); Michael Palmer is the foremost experimental poet Donna Honeycutt, Ap Sun (1988); First Figure (1984); Notes for Echo Lake of his generation and perhaps of the last several Treasurer (1981); Without Music (1977); The Circular Gates generations. A gorgeous writer who has taken Roberta Bearden, PSJ (1974); and Blake’s Newton (1972). He is also the cues from Wallace Stevens, the Black Mountain Recording Secretary author of a prose work, The Danish Notebook (Avec poets, John Ashbery, contemporary French poets, Lee Collins, Tw Books, 1999). the poetics of Octavio Paz, and from language Corresponding Secretary Palmer’s work, which is both alluringly lyrical and poetries. He is one of the most original craftsmen Dorothy Marshall, Tw intensely avant-garde, has inspired a wide range of at work in English at the present time. -

Roots and Routes Poetics at New College of California

Roots and Routes Poetics at New College of California Edited by Patrick James Dunagan Marina Lazzara Nicholas James Whittington Series in Creative Writing Studies Copyright © 2020 by the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Suite 1200, Wilmington, Malaga, 29006 Delaware 19801 Spain United States Series in Creative Writing Studies Library of Congress Control Number: 2020935054 ISBN: 978-1-62273-800-7 Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. Cover design by Vernon Press. Cover image by Max Kirkeberg, diva.sfsu.edu/collections/kirkeberg/bundles/231645 All individual works herein are used with permission, copyright owned by their authors. Selections from "Basic Elements of Poetry: Lecture Notes from Robert Duncan Class at New College of California," Robert Duncan are © the Jess Collins Trust. -

Curriculum Vitae Yerra Sugarman

SUGARMAN / 1 YERRA SUGARMAN, PH.D. Visiting Assistant Professor University of Toledo Dept. of English Language and Literature Mailstop 126 / 2801 West Bancroft St. Toledo, Ohio 43606 [email protected] Website: https://yerrasugarman.com/ ______________________________________________________________________________ EDUCATION Ph.D. University of Houston, Houston, TX Creative Writing and Literature (Poetry), December 2016 Dissertation: Spirit and Particle. A Book of Poems with a Critical Afterword Entitled “The Poetry of Grief as Resistance” Dissertation Committee: Kevin Prufer, Director; Tony Hoagland; David Mikics; Martha Serpas; Grace Schulman, External Reader Comprehensive Examination Areas: The History of Poetry and Poetics (From the Psalms to the Twentieth Century) The English Renaissance: Poetry, Drama, and a Special Focus on the Seventeenth-Century Devotional Lyric The Elegy in English from the Seventeenth Century to the Twenty-First Century M.A. The City College of The City University of New York Creative Writing (Poetry) Thesis: The Bag of Broken Glass. A Book of Poems Thesis Director: Marilyn Hacker; Second Reader: Jane Marcus M.F.A. Columbia University in the City of New York Visual Arts (With an Emphasis on Painting; Additional Focus on Critical Writing) B.F.A. Concordia University, Montreal, Quebec Visual Arts (magna cum laude) ______________________________________________________________________________ UNIVERSITY POSITIONS (Selected) 2018-Pressent Visiting Assistant Professor of Creative Writing (Full-Time), University