It Pains Me to Admit It Since My Father Is a Big Zappa Fan and I Hate To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frank Zappa and His Conception of Civilization Phaze Iii

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2018 FRANK ZAPPA AND HIS CONCEPTION OF CIVILIZATION PHAZE III Jeffrey Daniel Jones University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/ETD.2018.031 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Jones, Jeffrey Daniel, "FRANK ZAPPA AND HIS CONCEPTION OF CIVILIZATION PHAZE III" (2018). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 108. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/108 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. I agree that the document mentioned above may be made available immediately for worldwide access unless an embargo applies. -

The History of Rock, a Monthly Magazine That Reaps the Benefits of Their Extraordinary Journalism for the Reader Decades Later, One Year at a Time

L 1 A MONTHLY TRIP THROUGH MUSIC'S GOLDEN YEARS THIS ISSUE:1969 STARRING... THE ROLLING STONES "It's going to blow your mind!" CROSBY, STILLS & NASH SIMON & GARFUNKEL THE BEATLES LED ZEPPELIN FRANK ZAPPA DAVID BOWIE THE WHO BOB DYLAN eo.ft - ink L, PLUS! LEE PERRY I B H CREE CE BEEFHE RT+NINA SIMONE 1969 No H NgWOMI WI PIK IM Melody Maker S BLAST ..'.7...,=1SUPUNIAN ION JONES ;. , ter_ Bard PUN FIRS1tintFaBil FROM 111111 TY SNOW Welcome to i AWORD MUCH in use this year is "heavy". It might apply to the weight of your take on the blues, as with Fleetwood Mac or Led Zeppelin. It might mean the originality of Jethro Tull or King Crimson. It might equally apply to an individual- to Eric Clapton, for example, The Beatles are the saints of the 1960s, and George Harrison an especially "heavy person". This year, heavy people flock together. Clapton and Steve Winwood join up in Blind Faith. Steve Marriott and Pete Frampton meet in Humble Pie. Crosby, Stills and Nash admit a new member, Neil Young. Supergroups, or more informal supersessions, serve as musical summit meetings for those who are reluctant to have theirwork tied down by the now antiquated notion of the "group". Trouble of one kind or another this year awaits the leading examples of this classic formation. Our cover stars The Rolling Stones this year part company with founder member Brian Jones. The Beatles, too, are changing - how, John Lennon wonders, can the group hope to contain three contributing writers? The Beatles diversification has become problematic. -

Pynchon's Sound of Music

Pynchon’s Sound of Music Christian Hänggi Pynchon’s Sound of Music DIAPHANES PUBLISHED WITH SUPPORT BY THE SWISS NATIONAL SCIENCE FOUNDATION 1ST EDITION ISBN 978-3-0358-0233-7 10.4472/9783035802337 DIESES WERK IST LIZENZIERT UNTER EINER CREATIVE COMMONS NAMENSNENNUNG 3.0 SCHWEIZ LIZENZ. LAYOUT AND PREPRESS: 2EDIT, ZURICH WWW.DIAPHANES.NET Contents Preface 7 Introduction 9 1 The Job of Sorting It All Out 17 A Brief Biography in Music 17 An Inventory of Pynchon’s Musical Techniques and Strategies 26 Pynchon on Record, Vol. 4 51 2 Lessons in Organology 53 The Harmonica 56 The Kazoo 79 The Saxophone 93 3 The Sounds of Societies to Come 121 The Age of Representation 127 The Age of Repetition 149 The Age of Composition 165 4 Analyzing the Pynchon Playlist 183 Conclusion 227 Appendix 231 Index of Musical Instruments 233 The Pynchon Playlist 239 Bibliography 289 Index of Musicians 309 Acknowledgments 315 Preface When I first read Gravity’s Rainbow, back in the days before I started to study literature more systematically, I noticed the nov- el’s many references to saxophones. Having played the instru- ment for, then, almost two decades, I thought that a novelist would not, could not, feature specialty instruments such as the C-melody sax if he did not play the horn himself. Once the saxophone had caught my attention, I noticed all sorts of uncommon references that seemed to confirm my hunch that Thomas Pynchon himself played the instrument: McClintic Sphere’s 4½ reed, the contra- bass sax of Against the Day, Gravity’s Rainbow’s Charlie Parker passage. -

Warner/Reprise Loss Leaders Booklet

THE WARNER BROS. LOSS LEADERS SERIES (1969-1980) Depending On How You Count Them, 34 Essential Various Artist Collections From Another Time We figured it was about time to pull together all of the incredible Warner Bros. Loss Leaders releases dating back to 1969 (and even a little earlier). For those who lived through the era, Warner Bros. Records was winning the sales of an entire generation by signing and supporting some of music’s most uniquely groundbreaking recording artists… during music’s most uniquely groundbreak- ing time. With an appealingly irreverent style (“targeted youth marketing,” it would be called today), WB was making lifelong fans of the kids who entered into the label’s vast catalog of art- ists via the Loss Leaders series—advertised on inner sleeves & brochures, and offering generous selections priced at $1 per LP, $2 for doubles and $3 for their sole 3-LP release, Looney Tunes And Merrie Melodies. And that was including postage. Yes… those were the days, but back then there were very few ways, outside of cut-out bins or a five-finger discount, to score bulk music as cheaply. Warners unashamedly admitted that their inten- tions were to sell more records, by introducing listeners to music they weren’t hearing on their radios, or finding in many of their (still weakly distributed) record stores. And it seemed to work… because the series continued until 1980, and the program issued approximately 34 titles, by our questionable count (detailed in later posts). But, the oldsters among us all fondly remember the multi-paged, gatefold sleeves and inviting artwork/packaging that beckoned from the inner sleeves of our favorite albums, not to mention the assorted rarities, b-sides and oddities that dotted many of the releases. -

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020

Omega Auctions Ltd Catalogue 28 Apr 2020 1 REGA PLANAR 3 TURNTABLE. A Rega Planar 3 8 ASSORTED INDIE/PUNK MEMORABILIA. turntable with Pro-Ject Phono box. £200.00 - Approximately 140 items to include: a Morrissey £300.00 Suedehead cassette tape (TCPOP 1618), a ticket 2 TECHNICS. Five items to include a Technics for Joe Strummer & Mescaleros at M.E.N. in Graphic Equalizer SH-8038, a Technics Stereo 2000, The Beta Band The Three E.P.'s set of 3 Cassette Deck RS-BX707, a Technics CD Player symbol window stickers, Lou Reed Fan Club SL-PG500A CD Player, a Columbia phonograph promotional sticker, Rock 'N' Roll Comics: R.E.M., player and a Sharp CP-304 speaker. £50.00 - Freak Brothers comic, a Mercenary Skank 1982 £80.00 A4 poster, a set of Kevin Cummins Archive 1: Liverpool postcards, some promo photographs to 3 ROKSAN XERXES TURNTABLE. A Roksan include: The Wedding Present, Teenage Fanclub, Xerxes turntable with Artemis tonearm. Includes The Grids, Flaming Lips, Lemonheads, all composite parts as issued, in original Therapy?The Wildhearts, The Playn Jayn, Ween, packaging and box. £500.00 - £800.00 72 repro Stone Roses/Inspiral Carpets 4 TECHNICS SU-8099K. A Technics Stereo photographs, a Global Underground promo pack Integrated Amplifier with cables. From the (luggage tag, sweets, soap, keyring bottle opener collection of former 10CC manager and music etc.), a Michael Jackson standee, a Universal industry veteran Ric Dixon - this is possibly a Studios Bates Motel promo shower cap, a prototype or one off model, with no information on Radiohead 'Meeting People Is Easy 10 Min Clip this specific serial number available. -

Do You Know What You Are? You Are What You Is; You Is

\\server05\productn\H\HBK\26-1\HBK104.txt unknown Seq: 1 17-MAY-10 10:17 DO YOU KNOW WHAT YOU ARE? YOU ARE WHAT YOU IS; YOU IS WHAT YOU AM:1 INDIAN STATUS FOR THE PURPOSE OF FEDERAL CRIMINAL JURISDICTION AND THE CURRENT SPLIT IN THE COURTS OF APPEALS Brian L. Lewis* INTRODUCTION Who is an Indian for purposes of criminal prosecution in the United States’ federal courts under the Major Crimes Act, 18 U.S.C. § 1153?2 The statute does not say. While seemingly straightforward, the answer to this question may be complicated and uncertain. Moreover, if one is in the Eighth Circuit or the Ninth Circuit, the answer may differ. Historically, the test from U.S. v. Rogers3 determined Indian status for federal criminal prosecution. However, over time, as political, institutional and demo- graphic conditions changed, so did the test. Congress’ enactment of the Major Crimes Act, which was based on alarmism and devoid of a doctrinal foundation, changed the test for In- dian status and how it is applied. In the aftermath of the Court’s decision 1. FRANK ZAPPA, YOU ARE WHAT YOU IS (Zappa Records 1981). * Brian L. Lewis is a Staff Attorney with the Navajo Nation Department of Justice in Window Rock, Arizona. He is an enrolled member of the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma and a descendant of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma. He earned his Juris Doctor at the Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law at Arizona State University with an Indian Law Certificate and his Master’s Degree in International Relations and Political Economy at Washington State University with honors in both. -

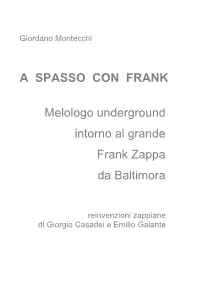

A Spasso Con Frank

Giordano Montecchi A SPASSO CON FRANK Melologo underground intorno al grande Frank Zappa da Baltimora reinvenzioni zappiane di Giorgio Casadei e Emilio Galante 0 [SENZA MUSICA] A Mister Edgard Varèse, 188 Sullivan Street, New York. Agosto 1957 Gentile Signore, forse ricorderà la mia stupida telefonata dello scorso gennaio... Mi chiamo Frank Zappa e ho 16 anni. Le sembrerà strano ma è da quando ho 13 anni che mi interesso alla sua musica. All’epoca l’unica formazione musicale che avevo era qualche rudimento di tecnica del tamburo. Negli ultimi due anni però ho composto alcuni brani musicali utilizzando una rigorosa tecnica dei dodici suoni con risultati che ricordano Anton Webern. Ho scritto due brevi quartetti per fiati e una breve sinfonia per legni ottoni e percussioni. Ultimamente guadagno qualche soldo per mantenermi con la mia blues band, The Blackouts. Dopo il college conto di continuare a comporre e penso mi sarebbero veramente utili i consigli di un veterano come lei. Se mi permettesse di farle visita anche solo per poche ore gliene sarei molto grato. Le sembrerà strano ma penso proprio di avere qualche nuova idea da offrirle in materia di composizione. La prego di rispondermi il più presto possibile perché non resterò a lungo a questo indirizzo. La ringrazio per l’attenzione. Cordiali saluti Frank Zappa Jr. ................... 2 1 PEACHES EN REGALIA [VAMP] I duri del rock lo sentono come loro proprietà esclusiva, come profeta anti- establishment. Gli accademici lo tollerano in quanto compositore... un’eccezione! per il mondo del rock. Chi lo vuole un giullare simbolo della trasgressione più anarcoide..... -

Compositions-By-Frank-Zappa.Pdf

Compositions by Frank Zappa Heikki Poroila Honkakirja 2017 Publisher Honkakirja, Helsinki 2017 Layout Heikki Poroila Front cover painting © Eevariitta Poroila 2017 Other original drawings © Marko Nakari 2017 Text © Heikki Poroila 2017 Version number 1.0 (October 28, 2017) Non-commercial use, copying and linking of this publication for free is fine, if the author and source are mentioned. I do not own the facts, I just made the studying and organizing. Thanks to all the other Zappa enthusiasts around the globe, especially ROMÁN GARCÍA ALBERTOS and his Information Is Not Knowledge at globalia.net/donlope/fz Corrections are warmly welcomed ([email protected]). The Finnish Library Foundation has kindly supported economically the compiling of this free version. 01.4 Poroila, Heikki Compositions by Frank Zappa / Heikki Poroila ; Front cover painting Eevariitta Poroila ; Other original drawings Marko Nakari. – Helsinki : Honkakirja, 2017. – 315 p. : ill. – ISBN 978-952-68711-2-7 (PDF) ISBN 978-952-68711-2-7 Compositions by Frank Zappa 2 To Olli Virtaperko the best living interpreter of Frank Zappa’s music Compositions by Frank Zappa 3 contents Arf! Arf! Arf! 5 Frank Zappa and a composer’s work catalog 7 Instructions 13 Printed sources 14 Used audiovisual publications 17 Zappa’s manuscripts and music publishing companies 21 Fonts 23 Dates and places 23 Compositions by Frank Zappa A 25 B 37 C 54 D 68 E 83 F 89 G 100 H 107 I 116 J 129 K 134 L 137 M 151 N 167 O 174 P 182 Q 196 R 197 S 207 T 229 U 246 V 250 W 254 X 270 Y 270 Z 275 1-600 278 Covers & other involvements 282 No index! 313 One night at Alte Oper 314 Compositions by Frank Zappa 4 Arf! Arf! Arf! You are reading an enhanced (corrected, enlarged and more detailed) PDF edition in English of my printed book Frank Zappan sävellykset (Suomen musiikkikirjastoyhdistys 2015, in Finnish). -

In Nomine Zappa, Zappatore: Sketch of an Hypothesis (S/Z2) + (Sv/Gw)

Document generated on 10/02/2021 1:56 p.m. Circuit Musiques contemporaines In nomine Zappa, Zappatore Sketch of an Hypothesis (S/Z2) + (sv/gw) In nomine Zappa, Zappatore Esquisse d’une hypothèse (S/Z2) + (sv/gw) John Rea Frank Zappa : 10 ans après Article abstract Volume 14, Number 3, 2004 A man's character is, as Heraclitus once observed, his destiny. Similarly, Frank Zappa noted that "You are what you is". In nomine Zappa, Zappatore proposes a URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/902330ar philological as well as iconographic deconstruction of the Italian name/mask DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/902330ar (persona), Zappa. The essay suggests that not only is a man's character his daimon but that, moreover, FZ was both an assiduous and subversive artistic See table of contents worker. Publisher(s) Les Presses de l'Université de Montréal ISSN 1183-1693 (print) 1488-9692 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this document Rea, J. (2004). In nomine Zappa, Zappatore: Sketch of an Hypothesis (S/Z2) + (sv/gw). Circuit, 14(3), 103–112. https://doi.org/10.7202/902330ar Tous droits réservés © Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, 2004 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. -

The Real Frank Zappa Book Contents

The Real Frank Zappa Book by Frank Zappa with Peter Occhiogrosso eVersion 3.0 - click for copyright info and scan notes THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED TO GAIL, THE KIDS, STEPHEN HAWKING AND KO-KO. F.Z. August 23, 1988 06:39:37 Contents INTRODUCTION -- Book? What Book? 1 How Weird Am I, Anyway? 2 There Goes the Neighborhood 3 An Alternative to College 4 Are We Having a Good Time Yet? 5 The Log Cabin 6 Send In the Clowns 7 Drool, Britannia 8 All About Music 9 A Chapter for My Dad 10 The One You've Been Waiting For 11 Sticks & Stones 12 America Drinks and Goes Marching 13 All About Schmucks 14 Marriage (as a Dada Concept) 15 "Porn Wars" 16 Church and State 17 Practical Conservatism 18 Failure 19 The Last Word Introduction Book? What Book? I don't want to write a book, but I'm going to do it anyway, because Peter Occhiogrosso is going to help me. He is a writer. He likes books -- he even reads them. I think it is good that books still exist, but they make me sleepy. The way we're going to do it is, Peter will come to California and spend a few weeks recording answers to 'fascinating questions,' then the tapes will be transcribed. Peter will edit them, put them on floppy discs, send them back to me, I will edit them again, and that result will be sent to Ann Patty at Poseidon Press, and she will make it come out to be 'A BOOK.' One of the reasons for doing this is the proliferation of stupid books (in several languages) which purport to be About Me . -

Gonzo Weekly #155

Subscribe to Gonzo Weekly http://eepurl.com/r-VTD Subscribe to Gonzo Daily http://eepurl.com/OvPez Gonzo Facebook Group https://www.facebook.com/groups/287744711294595/ Gonzo Weekly on Twitter https://twitter.com/gonzoweekly Gonzo Multimedia (UK) http://www.gonzomultimedia.co.uk/ Gonzo Multimedia (USA) http://www.gonzomultimedia.com/ 3 Dear Friends, Welcome to another issue of this singular periodical. I know that I say it every week, but it never ceases to amaze me how such a tiny band of brothers and sisters, the vast majority of whom are unpaid, manages to put out a full length magazine of such like to once again publicly thank my editorial quality every single week of the year. Before team particularly Doug, John, Corinna and I continue with this week’s musings I would Jessica, although it really goes against the 4 grain to single anyone out of such a hard who read this magazine. Some of you will, working and productive team. no doubt, be shocked by this revelation. DeMille is a fairly gung ho Republican One of my favourite authors is an American whose ethos would seem to be quite far thriller writer called Nelson DeMille who removed from the anarchist ethos of what I may not be familiar to many of the people write for this magazine, and indeed, how I live my life. But he does write cracking stories! Probably my favourite of his books is one called Word of Honour which tells a very interesting and morally intriguing tale. The main protagonist is a wealthy businessman who, at some time during the late 1980s, is on his way to work. -

Groupies and Other Electric Ladies Datasheet

TITLE INFORMATION Tel: +44 (0) 1394 389950 Email: [email protected] Web: https://www.accartbooks.com/uk Groupies and Other Electric Ladies The original 1969 Rolling Stone photographs by Baron Wolman Baron Wolman ISBN 9781851497942 Publisher ACC Art Books Binding Hardback Territory World Size 300 mm x 240 mm Pages 192 Pages Illustrations 200 b&w Price £40.00 For the first time in book form, these are the photographs taken by the legendary Baron Wolman for the February 1969 'Special Super-Duper Neat Issue' of Rolling Stone Key images from a time of explosive revolution in music and culture - featuring Pamela des Barres, Catherine James, Sally Mann, Cynthia Plaster Caster and many more The original chronicle of the women who became deeply influential style icons, integral to the worlds of musicians like Frank Zappa, The Doors, Led Zeppelin, The Rolling Stones, Captain Beefheart, Alice Cooper, The Who and Gram Parsons "Mr. Wolman's view of the women as style icons comes into sharp focus thanks to a new coffee-table book, Groupies and Other Electric Ladies. It collects his published portraits along with outtakes, contact sheets, the original articles from the issue and new essays that put the subjects into a modern context. The thick paper stock and oversize format emphasizes Mr. Wolman's view of the groupies as pioneers in hippie frippery." New York Times Style section "...style and fashion mattered greatly, were central to their presentation, and I became fascinated with them... I discovered what I believed was a subculture of chic and I thought it merited a story." Baron Wolman The 1960s witnessed a huge cultural revolution.