Identification of Rip Current Hazards Using Fluorescent Dye and Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (A Case Study of Drini Beach, Gunungkidul, Indonesia)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rip Current Observations Via Marine Radar

Rip Current Observations via Marine Radar Merrick C. Haller, M.ASCE1; David Honegger2; and Patricio A. Catalan3 Abstract: New remote sensing observations that demonstrate the presence of rip current plumes in X-band radar images are presented. The observations collected on the Outer Banks (Duck, North Carolina) show a regular sequence of low-tide, low-energy, morphologically driven rip currents over a 10-day period. The remote sensing data were corroborated by in situ current measurements that showed depth-averaged rip current velocities were 20e40 cm=s whereas significant wave heights were Hs 5 0:5e1 m. Somewhat surprisingly, these low-energy rips have a surface signature that sometimes extends several surf zone widths from shore and persists for periods of several hours, which is in contrast with recent rip current observations obtained with Lagrangian drifters. These remote sensing observations provide a more synoptic picture of the rip current flow field and allow the identification of several rip events that were not captured by the in situ sensors and times of alongshore deflection of the rip flow outside the surf zone. These data also contain a rip outbreak event where four separate rips were imaged over a 1-km stretch of coast. For potential comparisons of the rip current signature across other radar platforms, an example of a simply calibrated radar image is also given. Finally, in situ observations of the vertical structure of the rip current flow are given, and a threshold offshore wind stress (.0:02 m=s2)isfoundto preclude the rip current imaging. DOI: 10.1061/(ASCE)WW.1943-5460.0000229. -

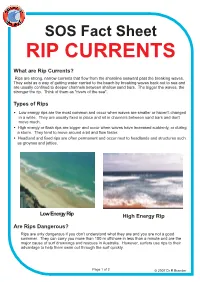

What Are Rip Currents? Types of Rips Are Rips Dangerous

What are Rip Currents? Rips are strong, narrow currents that flow from the shoreline seaward past the breaking waves. They exist as a way of getting water carried to the beach by breaking waves back out to sea and are usually confined to deeper channels between shallow sand bars. The bigger the waves, the stronger the rip. Think of them as "rivers of the sea". Types of Rips • Low energy rips are the most common and occur when waves are smaller or haven't changed in a while. They are usually fixed in place and sit in channels between sand bars and don't move much. • High energy or flash rips are bigger and occur when waves have increased suddenly, or during a storm. They tend to move around a bit and flow faster. • Headland and fixed rips are often permanent and occur next to headlands and structures such as groynes and jetties. Low Energy Rip High Energy Rip Are Rips Dangerous? Rips are only dangerous if you don't understand what they are and you are not a good swimmer. They can carry you more than 100 m offshore in less than a minute and are the major cause of surf drownings and rescues in Australia. However, surfers use rips to their advantage to help them swim out through the surf quickly. Page1of2 © 2007 Dr R Brander continued Spotting a Rip Since rips often sit in deeper channels between shallow sand bars, always spend 5-10 minutes looking at the surf zone for consistent darker and "calmer" areas of water that extend offshore between the breaking waves. -

Rip Current Generation and Management Implications in South Florida

MOJ Ecology & Environmental Sciences Research Article Open Access Rip current generation and management implications in south Florida Abstract Volume 3 Issue 3 - 2018 Miami Beach is one of the most dangerous beaches for rip current drownings in the Stephen B Leatherman United States. There are three principal wave generators that result in rip currents: Department of Earth & Environment, Florida International onshore winds associated with high pressure cells, swell waves produced by offshore University, USA nor’easters, and tropical storms. A logistic regression analysis showed a correlation between rip currents, wave height and month of the year even under low wave energy Correspondence: Stephen B Leatherman, Department of conditions at Miami area beaches. Most rips were found to occur during 15–20 knot Earth & Environment, Florida International University, 11200 onshore winds with 0.6–0.9m significant wave height. Eleven social, physical and SW 8th Street, Florida Miami, Florida 33199, USA, Tel 1305- safety factors make Miami Beach a rip current hotspot and pose a major coastal 3482-00, Email [email protected] management challenge. Received: November 16, 2017 | Published: May 31, 2018 Keywords: rip current forecasting, rip current drowning, rip current hot spots, safety factors, beaches Introduction generated by 0.6 to 1.2 m waves during fair–weather conditions, which seem like perfect beach days, making these rips deceptively dangerous South Florida is a tourism destination that is well known for its to bathers. Another type of rip generator is nor’easters offshore the beaches. Miami Beach is one of the ten most famous beaches in the mid–Atlantic and Northeast coast, which produce large swells (Figure 1 world and boasts of tens of millions of visitors each year. -

Reef Rip Current Generated by Tide and Wave During Summer Season: Field Observation Conducted in Yoshiwara Coast, Ishigakijima, Okinawa, Japan

Proceedings of the 11th International Coral Reef Symposium, Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, 7-11 July 2008 Session number 15 Reef Rip Current Generated by Tide and Wave during Summer Season: Field Observation Conducted in Yoshiwara Coast, Ishigakijima, Okinawa, Japan M.P. de Leon1, R. Nishi2, F. Kumasaka3, T. Takaesu4, R. Kitamura5, A. Otani6 1) Graduate School of Science and Engineering, Kagoshima University, 1-21-40 Korimoto, Kagoshima, Japan 2) Faculty of Fisheries, Kagoshima University, 4-50-20 Shimoarata, Kagoshima, Japan 3) Japan Hydrographic Association, Tsukiji, Tokyo, Japan 4) Marine Information Science, 11th Japan Coast Guard, Naha, Okinawa, Japan 5) Department of Ocean Civil Engineering, Kagoshima University, 1-21-40 Korimoto, Kagoshima, Japan 6) IO Technic, 2-28-19 Minami, Tsukushino, Machida, Tokyo, Japan Abstract. In 2004 and 2005, five drowning accidents in Ishigakijima, Okinawa were documented by Japan Coast Guard and were found to be caused by a strong offshore current commonly known as “reef current”. This type of current has been identified to be responsible in generating the circulation of water and transportation of sediment in coral reefs. In this paper, however, high-speed offshore current in coral reefs is specifically referred to as “reef rip current”. Considering that the generation mechanism of reef rip current is not revealed yet, the researchers conducted a hydrodynamic study in Yoshiwara Coast, Ishigakijima, Okinawa in two phases (normal and storm conditions) during summer season to determine the location and time of occurrence of the strong offshore current that will significantly address safe utilization of coral reef and carbonate beach thereby reducing drowning accidents. -

Earth's Atmosphere

Earth & Space Science Packet April 20th- May 1st, 2020 Griffin & King This packet contains: 1. Worksheets for Ocean Floor, Ocean Water and Ocean Life, Earth’s Atmosphere 2. All About Waves Article 3. Atmospheric Density Lab What needs to be turned in for a GRADE? ● Worksheets with questions answered (Ocean Floor and Ocean Water/Life is April 20-24; Atmosphere is April 27-May 1) Optional/Enrichment included: ● Labs ● Science Articles If these are completed, we would LOVE for you to share: Send us pictures on remind/email, or tag @TheBurgScience and #Team DCS on Twitter EARTH & SPACE SCIENCE GRIFFIN & KING THE OCEAN FLOOR ___ THE VAST WORLD OCEAN ● Nearly 70 percent of Earth’s surface is covered by the global ocean. ● Oceanography is a science that draws on the methods and knowledge of geology, chemistry, physics, and biology to study all aspects of the world ocean. ● The world ocean can be divided into four main ocean basins- the Pacific Ocean, the Atlantic Ocean, the Indian Ocean, and the Arctic Ocean. ● The topography of the ocean floor is as diverse as that of continents. ● Bathymetry (bathos=depth, metry=measurement) is the measurement of ocean depths and the charting of the shape or topography of the ocean floor. ● Today’s technology- particular sonar, satellites, and submersibles- allows scientists to study the ocean floor in a more efficient and precise manner than ever before. ● Sonar is an acronym for sound navigation and ranging. Sonar calculates ocean depth by recording the time it takes sound waves to reach the ocean floor and return. -

Aucelli Et Al

Rip current evidence by hydrodynamic simulations, bathymetric surveys and UAV observation Guido Benassai1, Pietro Aucelli2, Giorgio Budillon2, Massimo De Stefano2, Diana Di Luccio2, Gianluigi Di Paola2, Raffaele Montella2, Luigi Mucerino3, Mario Sica4, and Micla Pennetta5 1Department of Engineering, University of Naples Parthenope 2Department of Science and Technology, University of Naples Parthenope 3Department of Earth, Environment and Life Sciences, University of Genova 4Autorità di Bacino Campania Centrale 5Department of Earth, Environment and Resources Sciences, University of Naples Federico II Correspondence to: Guido Benassai ([email protected]) Abstract. The prediction of the formation, spacing and location of rip currents is a scientific challenge that can be achieved by means of different complementary methods. In this paper the analysis of numerical and experimental data, including RPAS (Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems) observations, allowed to detect the presence of rip currents and rip channels at the mouth of Sele river, in the Gulf of Salerno, southern Italy. The dataset used to analyze these phenomena consisted of two different 5 bathymetric surveys, a detailed sediment analysis and a set of high-resolution wave numerical simulations, completed with Google EarthTM images and RPAS observations. The grain size trend analysis and the numerical simulations allowed to identify the rip current occurrence, forced by topographically constrained channels incised on the seabed, which were compared with observations. Keywords: rip-currents, hydrodynamic simulations, transport vectors, UAV observation. 10 1 Introduction The monitoring and the forecasting of beach processes become particularly critical along the unstable coastal areas, possibly subjected to coastal vulnerability (Di Paola et al. (2014)), and coastal risk due to sea level rise (Benassai et al. -

Rip-Current-At-Pangandaran

GSJ: VOLUME 6, ISSUE 6, JUNE 2018 202 GSJ: Volume 6, Issue 6, June 2018, Online: ISSN 2320-9186 www.globalscientificjournal.com RIP CURRENT AT PANGANDARAN AND PALABUHAN RATU Rona Sandro1, Noir P Purba1 2, Ibnu Faizal3, Lintang P S Yuliadi3 1 KOMITMEN Research Group, Padjadjaran University 2 Marine Research Laboratory (MEAL), Padjadjaran University 3 Marine Science Departement, Faculty of Fisheries and Marine Science, Padjadjaran University Jl. Raya Bandung Sumedang KM. 21, Jatinangor 45363, Indonesia Email: [email protected] KeyWords Currents, Wave, Bathymetri, Pangandaraan, Palabuhanratu, Stains (dye balls) ABSTRACT This research aims to know the causes, types, and mechanisms of the rip current at Pangandaran and Palabuhanratu. The methods used in this research are image data analysis, visual observation, and field observations in June and September 2015. The image data obtained from Google Earth, visual observation with the aid of a video camera and field observations with measurements of oceanographic parameters of a wave, bathymetry, currents, and staining using dye balls. The results showed the length and width of rip currents at Pangandaran around 300 meters and 90 meters, while in Palabuhanratu which ranges from 150 meters and 40 meters. Wave velocity (C) is 1.47 m/s and 1.51 m/s in Pangandaran, 1.13 m/s and 1.04 m/s in Palabuhanratu. The significant wave height (Hs) in Pangandaran is 1.42; while in Palabuhanratu is 1.58 meters. Bathymetry near the beach in both locations showed a morphological appearance of the beach cup with water depth is 0-7 meters in the break zone. -

2. Coastal Processes

CHAPTER 2 2. Coastal processes Coastal landscapes result from by weakening the rock surface and driving nearshore sediment the interaction between coastal to facilitate further sediment transport processes. Wind and tides processes and sediment movement. movement. Biological, biophysical are also significant contributors, Hydrodynamic (waves, tides and biochemical processes are and are indeed dominant in coastal and currents) and aerodynamic important in coral reef, salt marsh dune and estuarine environments, (wind) processes are important. and mangrove environments. respectively, but the action of Weathering contributes significantly waves is dominant in most settings. to sediment transport along rocky Waves Information Box 2.1 explains the coasts, either directly through Ocean waves are the principal technical terms associated with solution of minerals, or indirectly agents for shaping the coast regular (or sinusoidal) waves. INFORMATION BOX 2.1 TECHNICAL TERMS ASSOCIATED WITH WAVES Important characteristics of regular, Natural waves are, however, wave height (Hs), which is or sinusoidal, waves (Figure 2.1). highly irregular (not sinusoidal), defined as the average of the • wave height (H) – the difference and a range of wave heights highest one-third of the waves. in elevation between the wave and periods are usually present The significant wave height crest and the wave trough (Figure 2.2), making it difficult to off the coast of south-west • wave length (L) – the distance describe the wave conditions in England, for example, is, on between successive crests quantitative terms. One way of average, 1.5m, despite the area (or troughs) measuring variable height experiencing 10m-high waves • wave period (T) – the time from is to calculate the significant during extreme storms. -

Rip Current Generation, Flow Characteristics and Implications for Beach Safety in South Florida

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 11-9-2018 Rip Current Generation, Flow Characteristics and Implications for Beach Safety in South Florida Stephen B. Leatherman Florida International University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Geomorphology Commons, and the Other Earth Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Leatherman, Stephen B., "Rip Current Generation, Flow Characteristics and Implications for Beach Safety in South Florida" (2018). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3884. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/3884 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida RIP CURRENT GENERATION, FLOW CHARACTERISTICS AND IMPLICATIONS FOR BEACH SAFETY IN SOUTH FLORIDA A dissertation submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSPHY in GEOSCIENCES by Stephen Beach Leatherman 2018 To: Dean Michael R. Heithaus College of Arts, Sciences and Education This dissertation, written by Stephen Beach Leatherman, and entitled Rip Current Generation, Flow Characteristics and Implications for Beach Safety in South Florida, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgement. We have read this dissertation and recommended that it be approved. _______________________________________________ Michael Sukop _______________________________________________ Shu-Ching Chen _______________________________________________ Dean Whitman, Co-Major Professor _______________________________________________ Keqi Zhang, Co-Major Professor Date of Defense: November 9, 2018 The dissertation of Stephen Beach Leatherman is approved. -

Natural and Social Features of Monmouth County

NATURAL and CULTURAL FEATURES of MONMOUTH COUNTY Background Reading for Environmental Health Investigations MCHD Rev. 07/29/13 INTRODUCTION Monmouth County in central New Jersey is entirely located within the Inner and Outer Coastal Plain, part of the Atlantic Plain geology that extends 2200 miles from Cape Cod to the Yucatan Peninsula (USGS, 2003). There are 53 municipalities within a land area of 471.74 square miles of highly erodible soils that were originally deposited as runoff from the slopes of the Appalachians (MCPB, 2005). Some County History Following Henry Hudson’s exploration of the Sandy Hook shoreline in 1609, Monmouth County was predominantly under Dutch influence from about 1614 to 1664 (Colts Neck Historical Society, 1965). The New Jersey coastline had previously been sited and claimed for England (Giovanni Caboto, 1497), France (Giovanni de Verrazano, 1524), and Spain (Estevan Gomez, 1525); and had been Scheyichbi, Long Land Water, to the Lenape Indian Nation (Colts Neck Historical Society, 1965). Four major trails used by Native Americans terminated at the Navesink River: the Achkinkeshacky (Hackensack) Trail from the Hudson River; the Minisink Trail from the Great Lakes region; the Raritan-Lopotcong Trail from the west, and the Crosweeksung Trail from the southwest. This last trail entered NJ at Trenton, passed through Freehold to the Yellow Brook at Colts Neck, where it split into a northern path to Tinton Falls and Red Bank, and a southern path to the Shark River and Manasquan (NFECA, 2009). The first settlers in Middletown, the oldest settlement in NJ, are reported to have arrived as early as 1613, seven years before the Pilgrims landed in Massachusetts; Middletown was originally called Shaquaset by the Lenape (Boyd, 2004; Mandeville, 1927). -

Modelling Beach Processes – Introductory Materials

OCN 100 Lab Modelling Beach Processes – Introductory Materials Introduction Coastlines are dynamic features, changing shape continually and confounding human efforts to tame them. Why are coastal areas so moody? Why does each passing storm leave its imprint (erosion, deposition, or both) on a coastline that has existed for millennia? The answers to these questions lie in the nature of coastal processes, the ways in which waves affect the coast, the source of sediment, and human interference in the whole scheme. This module will help you explore these processes and see how society’s interactions can interrupt or divert the flow of sand along our beaches. Each of the ten sections described here include a link to a short animation. It is recommended that you read the material first for key concepts and vocabulary and then view the animation to assist with visualization of the material. Once you are comfortable with the concept(s) presented in the section, answer the worksheet questions before moving on to the next section. 1 - Beach Anatomy (Animation 0:32 seconds) Beaches are a common sight along coastlines and they represent areas where deposition of sediment takes place along a shoreline. In many areas, beaches are a part of the mainland: in other areas, the beach is a part of a series of “barrier” islands off the mainland coast. The diagram presented in the animation labels the main parts of a beach system. Although not all the parts identified are present at all beaches, this scene is a common one along sandy beaches around the world. -

Physical Oceanography

Physical Oceanography 1. Ocean, Origin, Geology 2. Geography, Topography 3. Temperature, Salinity, Density and Oxygen – Horizontal/Vertical 4. Mixed Layer 5. Water Masses 6. General Circulation of the Oceans - Thermohaline Circulation - Wind driven circulation 7. Upper ocean processes, heat fluxes MSc Atmospheric Sciences 2016 IITM-University of Pune Roxy Mathew Koll :: CCCR/IITM The Ocean Areas of Earth’s surface above and below sea level as a percentage of the total area of Earth (in 100m intervals). Data from Becker et al. (2009). 1. The ocean covers 71% of Earth’s surface 2. The ocean contains 97% of the water on Earth 3. The ocean is Earth’s most important feature 4. They are only temporary features of a single world ocean 5. Average ocean depth is about 4½ times greater than the average height of the continents above sea level Origin of the Ocean 1. Source: The major trapped volatile during the formation of Earth was water (H2O). Others included nitrogen (N2), the most abundant gas in the atmosphere, carbon dioxide (CO2), and hydrochloric acid (HCl), which was the source of the chloride in sea salt (mostly NaCl). 2. Outgassing: Ocean had its origin from the prolonged escape of water vapor and other gases from the molten igneous rocks of the Earth to the clouds surrounding the cooling Earth. 3. Cooling and Rains: After the Earth's surface had cooled to a temperature below the boiling point of water, rain began to fall and continued to fall for centuries. 4. Present state: As the water drained into the great hollows in the Earth's surface, the primeval ocean came into existence, about 4billion years ago.