Rip Current Safety Presentation Length: Approximately 30 Minutes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Observations of Nearshore Infragravity Waves: Seaward and Shoreward Propagating Components A

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 107, NO. C8, 3095, 10.1029/2001JC000970, 2002 Observations of nearshore infragravity waves: Seaward and shoreward propagating components A. Sheremet,1 R. T. Guza,2 S. Elgar,3 and T. H. C. Herbers4 Received 14 May 2001; revised 5 December 2001; accepted 20 December 2001; published 6 August 2002. [1] The variation of seaward and shoreward infragravity energy fluxes across the shoaling and surf zones of a gently sloping sandy beach is estimated from field observations and related to forcing by groups of sea and swell, dissipation, and shoreline reflection. Data from collocated pressure and velocity sensors deployed between 1 and 6 m water depth are combined, using the assumption of cross-shore propagation, to decompose the infragravity wave field into shoreward and seaward propagating components. Seaward of the surf zone, shoreward propagating infragravity waves are amplified by nonlinear interactions with groups of sea and swell, and the shoreward infragravity energy flux increases in the onshore direction. In the surf zone, nonlinear phase coupling between infragravity waves and groups of sea and swell decreases, as does the shoreward infragravity energy flux, consistent with the cessation of nonlinear forcing and the increased importance of infragravity wave dissipation. Seaward propagating infragravity waves are not phase coupled to incident wave groups, and their energy levels suggest strong infragravity wave reflection near the shoreline. The cross-shore variation of the seaward energy flux is weaker than that of the shoreward flux, resulting in cross-shore variation of the squared infragravity reflection coefficient (ratio of seaward to shoreward energy flux) between about 0.4 and 1.5. -

Rip Current Observations Via Marine Radar

Rip Current Observations via Marine Radar Merrick C. Haller, M.ASCE1; David Honegger2; and Patricio A. Catalan3 Abstract: New remote sensing observations that demonstrate the presence of rip current plumes in X-band radar images are presented. The observations collected on the Outer Banks (Duck, North Carolina) show a regular sequence of low-tide, low-energy, morphologically driven rip currents over a 10-day period. The remote sensing data were corroborated by in situ current measurements that showed depth-averaged rip current velocities were 20e40 cm=s whereas significant wave heights were Hs 5 0:5e1 m. Somewhat surprisingly, these low-energy rips have a surface signature that sometimes extends several surf zone widths from shore and persists for periods of several hours, which is in contrast with recent rip current observations obtained with Lagrangian drifters. These remote sensing observations provide a more synoptic picture of the rip current flow field and allow the identification of several rip events that were not captured by the in situ sensors and times of alongshore deflection of the rip flow outside the surf zone. These data also contain a rip outbreak event where four separate rips were imaged over a 1-km stretch of coast. For potential comparisons of the rip current signature across other radar platforms, an example of a simply calibrated radar image is also given. Finally, in situ observations of the vertical structure of the rip current flow are given, and a threshold offshore wind stress (.0:02 m=s2)isfoundto preclude the rip current imaging. DOI: 10.1061/(ASCE)WW.1943-5460.0000229. -

Mapping Turbidity Currents Using Seismic Oceanography Title Page Abstract Introduction 1 2 E

Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Ocean Sci. Discuss., 8, 1803–1818, 2011 www.ocean-sci-discuss.net/8/1803/2011/ Ocean Science doi:10.5194/osd-8-1803-2011 Discussions OSD © Author(s) 2011. CC Attribution 3.0 License. 8, 1803–1818, 2011 This discussion paper is/has been under review for the journal Ocean Science (OS). Mapping turbidity Please refer to the corresponding final paper in OS if available. currents using seismic E. A. Vsemirnova and R. W. Hobbs Mapping turbidity currents using seismic oceanography Title Page Abstract Introduction 1 2 E. A. Vsemirnova and R. W. Hobbs Conclusions References 1Geospatial Research Ltd, Department of Earth Sciences, Tables Figures Durham University, Durham DH1 3LE, UK 2Department of Earth Sciences, Durham University, Durham DH1 3LE, UK J I Received: 25 May 2011 – Accepted: 12 August 2011 – Published: 18 August 2011 J I Correspondence to: R. W. Hobbs ([email protected]) Published by Copernicus Publications on behalf of the European Geosciences Union. Back Close Full Screen / Esc Printer-friendly Version Interactive Discussion 1803 Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Abstract OSD Using a combination of seismic oceanographic and physical oceanographic data ac- quired across the Faroe-Shetland Channel we present evidence of a turbidity current 8, 1803–1818, 2011 that transports suspended sediment along the western boundary of the Channel. We 5 focus on reflections observed on seismic data close to the sea-bed on the Faroese Mapping turbidity side of the Channel below 900m. Forward modelling based on independent physi- currents using cal oceanographic data show that thermohaline structure does not explain these near seismic sea-bed reflections but they are consistent with optical backscatter data, dry matter concentrations from water samples and from seabed sediment traps. -

Infragravity Wave Energy Partitioning in the Surf Zone in Response to Wind-Sea and Swell Forcing

Journal of Marine Science and Engineering Article Infragravity Wave Energy Partitioning in the Surf Zone in Response to Wind-Sea and Swell Forcing Stephanie Contardo 1,*, Graham Symonds 2, Laura E. Segura 3, Ryan J. Lowe 4 and Jeff E. Hansen 2 1 CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere, Crawley 6009, Australia 2 Faculty of Science, School of Earth Sciences, The University of Western Australia, Crawley 6009, Australia; [email protected] (G.S.); jeff[email protected] (J.E.H.) 3 Departamento de Física, Universidad Nacional, Heredia 3000, Costa Rica; [email protected] 4 Faculty of Engineering and Mathematical Sciences, Oceans Graduate School, The University of Western Australia, Crawley 6009, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 18 September 2019; Accepted: 23 October 2019; Published: 28 October 2019 Abstract: An alongshore array of pressure sensors and a cross-shore array of current velocity and pressure sensors were deployed on a barred beach in southwestern Australia to estimate the relative response of edge waves and leaky waves to variable incident wind wave conditions. The strong sea 1 breeze cycle at the study site (wind speeds frequently > 10 m s− ) produced diurnal variations in the peak frequency of the incident waves, with wind sea conditions (periods 2 to 8 s) dominating during the peak of the sea breeze and swell (periods 8 to 20 s) dominating during times of low wind. We observed that edge wave modes and their frequency distribution varied with the frequency of the short-wave forcing (swell or wind-sea) and edge waves were more energetic than leaky waves for the duration of the 10-day experiment. -

Climate Change Report for Gulf of the Farallones and Cordell

Chapter 6 Responses in Marine Habitats Sea Level Rise: Intertidal organisms will respond to sea level rise by shifting their distributions to keep pace with rising sea level. It has been suggested that all but the slowest growing organisms will be able to keep pace with rising sea level (Harley et al. 2006) but few studies have thoroughly examined this phenomenon. As in soft sediment systems, the ability of intertidal organisms to migrate will depend on available upland habitat. If these communities are adjacent to steep coastal bluffs it is unclear if they will be able to colonize this habitat. Further, increased erosion and sedimentation may impede their ability to move. Waves: Greater wave activity (see 3.3.2 Waves) suggests that intertidal and subtidal organisms may experience greater physical forces. A number of studies indicate that the strength of organisms does not always scale with their size (Denny et al. 1985; Carrington 1990; Gaylord et al. 1994; Denny and Kitzes 2005; Gaylord et al. 2008), which can lead to selective removal of larger organisms, influencing size structure and species interactions that depend on size. However, the relationship between offshore significant wave height and hydrodynamic force is not simple. Although local wave height inside the surf zone is a good predictor of wave velocity and force (Gaylord 1999, 2000), the relationship between offshore Hs and intertidal force cannot be expressed via a simple linear relationship (Helmuth and Denny 2003). In many cases (89% of sites examined), elevated offshore wave activity increased force up to a point (Hs > 2-2.5 m), after which force did not increase with wave height. -

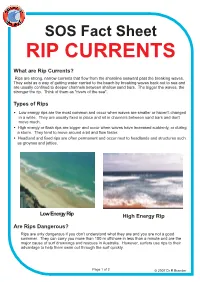

What Are Rip Currents? Types of Rips Are Rips Dangerous

What are Rip Currents? Rips are strong, narrow currents that flow from the shoreline seaward past the breaking waves. They exist as a way of getting water carried to the beach by breaking waves back out to sea and are usually confined to deeper channels between shallow sand bars. The bigger the waves, the stronger the rip. Think of them as "rivers of the sea". Types of Rips • Low energy rips are the most common and occur when waves are smaller or haven't changed in a while. They are usually fixed in place and sit in channels between sand bars and don't move much. • High energy or flash rips are bigger and occur when waves have increased suddenly, or during a storm. They tend to move around a bit and flow faster. • Headland and fixed rips are often permanent and occur next to headlands and structures such as groynes and jetties. Low Energy Rip High Energy Rip Are Rips Dangerous? Rips are only dangerous if you don't understand what they are and you are not a good swimmer. They can carry you more than 100 m offshore in less than a minute and are the major cause of surf drownings and rescues in Australia. However, surfers use rips to their advantage to help them swim out through the surf quickly. Page1of2 © 2007 Dr R Brander continued Spotting a Rip Since rips often sit in deeper channels between shallow sand bars, always spend 5-10 minutes looking at the surf zone for consistent darker and "calmer" areas of water that extend offshore between the breaking waves. -

Identification of Rip Current Hazards Using Fluorescent Dye and Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (A Case Study of Drini Beach, Gunungkidul, Indonesia)

https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-2021-221 Preprint. Discussion started: 23 August 2021 c Author(s) 2021. CC BY 4.0 License. Identification of Rip Current Hazards Using Fluorescent Dye And Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (A Case Study Of Drini Beach, Gunungkidul, Indonesia) 5 1Hendy Fatchurohman1, Alfiatun Nur Khasanah1, Ahmad Cahyadi2 1Department of Earth Science, Vocational College, Universitas Gadjah Mada. Sekip Utara Jalan Kaliurang, Bulaksumur, Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 55281 2Department of Environmental Geography, Faculty of Geography, Universitas Gadjah Mada. Sekip Utara Jalan Kaliurang, 10 Bulaksumur, Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 55281 Correspondence to: Hendy Fatchurohman ([email protected]) Abstract. Coastal tourism is a leading sector substantially contributing to the regional income of Gunungkidul Regency, 15 Indonesia. However, with more tourists visiting the beach, more lives are threatened by coastal hazards. Rip currents are a channel of powerful, narrow, fast-moving water that can carry floating objects away from the shore, presenting one of the most common coastal hazards to swimmers. Unfortunately, most tourists are unaware of rip currents and their threats and how to avoid them. This study was designed to identify the types and dimensions of rip current in one of the regency’s tourist attractions, Drini Beach. For this purpose, an environmentally friendly fluorescent dye, Uranine, was injected from the 20 shoreline, then the velocity and direction of its movements were observed from aerial video footage captured with a drone. Results showed stationary rip currents with a narrow channel, called a channel rip, with the mean dimensions: 250 m from the shoreline to the head and 10.25 m in width. -

Download Presentation

WaveWave drivendriven sea-levelsea-level anomalyanomaly atat MidwayMidway AtollAtoll RonRon HoekeHoeke CSIROCSIRO SeaSea LevelLevel andand CoastsCoasts JeromeJerome AucanAucan LaboratoireLaboratoire d'Etudesd'Etudes enen GéophysiqueGéophysique etet OcéanographieOcéanographie SpatialeSpatiale (LEGOS),(LEGOS), IRDIRD MarkMark MerrifieldMerrifield SOESTSOEST –– UniversityUniversity ofof HawaiiHawaii Funding:Funding: ••NOAANOAA CRCPCRCP ••JIMARJIMAR –– UniversityUniversity ofof HawaiiHawaii ••AustralianAustralian InstituteInstitute ofof MarineMarine ScienceScience (AIMS)(AIMS) ••CSIROCSIRO SeaSea LevelLevel andand CoastsCoasts ((AusAID)AusAID) photo: Scott Smithers WaveWave set-upset-up atat PacificPacific atollsatolls andand islandsislands “..the power of the breaking waves is utilized to maintain a water level just inside the surf zone about 1.5 ft above sea level.” Munk and Sargent (1948) Adjustment of Bikini Atoll to waves, Transactions, Am. Geo. Union, 29(6), 855-860. Wave set-up may be “as much as 20% of the incident wave height.” Tait, R. J. (1972) Wave Set-Up on Coral Reefs, J. Geophys. Res., 77(12). WaveWave set-upset-up atat PacificPacific atollsatolls andand islandsislands Steep-sloped Continental Shelf: islands/atolls: Wave dissipation Wave dissipation close farther offshore to shore/reef edge Smaller waves Larger waves Larger storm surge Smaller storm surge Graber et al. (2006) Coastal forecasts and storm surge predictions for tropical cyclones: A timely partnership program, Oceanography, 19(1), 130–141. PacificPacific wavewave climateclimate Hoeke et al. (2011) J. Geophys. Res., 116(C4), C04018. WaveWave set-upset-up inundationinundation eventsevents Nov. 28, 1979 Pohnpei Majuro Dec. 8, 2008 Fiji T imes,May 21, 2011 Takuu Dec. 10, 2008 Caldwell,Vitousek, Aucan (2009), Frequency and Duration of Coinciding High Surf and Tides along the North Shore of Oahu, Hawaii, 1981-2007, J. -

Rip Current Generation and Management Implications in South Florida

MOJ Ecology & Environmental Sciences Research Article Open Access Rip current generation and management implications in south Florida Abstract Volume 3 Issue 3 - 2018 Miami Beach is one of the most dangerous beaches for rip current drownings in the Stephen B Leatherman United States. There are three principal wave generators that result in rip currents: Department of Earth & Environment, Florida International onshore winds associated with high pressure cells, swell waves produced by offshore University, USA nor’easters, and tropical storms. A logistic regression analysis showed a correlation between rip currents, wave height and month of the year even under low wave energy Correspondence: Stephen B Leatherman, Department of conditions at Miami area beaches. Most rips were found to occur during 15–20 knot Earth & Environment, Florida International University, 11200 onshore winds with 0.6–0.9m significant wave height. Eleven social, physical and SW 8th Street, Florida Miami, Florida 33199, USA, Tel 1305- safety factors make Miami Beach a rip current hotspot and pose a major coastal 3482-00, Email [email protected] management challenge. Received: November 16, 2017 | Published: May 31, 2018 Keywords: rip current forecasting, rip current drowning, rip current hot spots, safety factors, beaches Introduction generated by 0.6 to 1.2 m waves during fair–weather conditions, which seem like perfect beach days, making these rips deceptively dangerous South Florida is a tourism destination that is well known for its to bathers. Another type of rip generator is nor’easters offshore the beaches. Miami Beach is one of the ten most famous beaches in the mid–Atlantic and Northeast coast, which produce large swells (Figure 1 world and boasts of tens of millions of visitors each year. -

Stratospheric Transport

Journal of the Meteorological Society of Japan, Vol. 80, No. 4B, pp. 793--809, 2002 793 Stratospheric Transport R. Alan PLUMB Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA (Manuscript received 3 July 2001, in revised form 15 February 2002) Abstract Improvements in our understanding of transport processes in the stratosphere have progressed hand in hand with advances in understanding of stratospheric dynamics and with accumulating remote and in situ observations of the distributions of, and relationships between, stratospheric tracers. It is conve- nient to regard the stratosphere as being separated into four regions: the summer hemisphere, the tropics, the wintertime midlatitude ‘‘surf zone’’, and the winter polar vortex. Stratospheric transport is dominated by mean diabatic advection (upwelling in the tropics, downwelling in the surf zone and the vortex) and, especially, by rapid isentropic stirring within the surf zone. These characteristics determine the global-scale distributions of tracers, and their mutual relationships. Despite our much-improved understanding of these processes, many chemical transport models still appear to exhibit significant shortcomings in simulating stratospheric transport, as is evidenced by their tendency to underestimate the age of stratospheric air. 1. Introduction have opposite large-scale gradients (HF has a stratospheric source and tropospheric sink, It has long been recognized that strato- CH a tropospheric source and stratospheric spheric trace gases with sufficiently weak 4 sink); nevertheless, the shapes of their iso- chemical sources and sinks have similar global pleths are very similar, with isopleths bulging distributions, in the sense that their isopleths upward in the tropics and poleward/downward (surfaces of constant mixing ratio) have similar slopes in the extratropics. -

Turbulence in the Swash and Surf Zones: a Review

Coastal Engineering 45 (2002) 129–147 www.elsevier.com/locate/coastaleng Turbulence in the swash and surf zones: a review Sandro Longo a,*, Marco Petti b,1, Inigo J. Losada c,2 aDepartment of Civil Engineering, University of Parma, Parco Area delle Scienze, 181/A, 43100 Parma, Italy bDipartimento di Georisorse e Territorio, Faculty of Engineering, University of Udine, Via del Cotonificio, 114, 33100 Udine, Italy cOcean and Coastal Research Group, Universidad de Cantabria, E.T.S.I.C.C. y P. Av. de los Castros s/n, 39005 Santander, Spain Abstract This paper reviews mainly conceptual models and experimental work, in the field and in the laboratory, dedicated during the last decades to studying turbulence of breaking waves and bores moving in very shallow water and in the swash zone. The phenomena associated with vorticity and turbulence structures measured are summarised, including the measurement techniques and the laboratory generation of breaking waves or of flow fields sharing several characteristics with breaking waves. The effect of air entrapment during breaking is discussed. The limits of the present knowledge, especially in modelling a two- or three-phase system, with air and sediment entrapped at high turbulence level, and perspectives of future research are discussed. D 2002 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved. Keywords: Swash zone; Surf zone; Breaking waves; Turbulence; Length scales; Coastal hydrodynamics 1. Introduction short and long waves, currents, turbulence and vorti- ces may be present. Therefore, the hydrodynamics to The swash zone is defined as the part of the beach be found in the swash zone is largely determined by between the minimum and maximum water levels the boundary conditions imposed by the beach face during wave runup and rundown. -

Reef Rip Current Generated by Tide and Wave During Summer Season: Field Observation Conducted in Yoshiwara Coast, Ishigakijima, Okinawa, Japan

Proceedings of the 11th International Coral Reef Symposium, Ft. Lauderdale, Florida, 7-11 July 2008 Session number 15 Reef Rip Current Generated by Tide and Wave during Summer Season: Field Observation Conducted in Yoshiwara Coast, Ishigakijima, Okinawa, Japan M.P. de Leon1, R. Nishi2, F. Kumasaka3, T. Takaesu4, R. Kitamura5, A. Otani6 1) Graduate School of Science and Engineering, Kagoshima University, 1-21-40 Korimoto, Kagoshima, Japan 2) Faculty of Fisheries, Kagoshima University, 4-50-20 Shimoarata, Kagoshima, Japan 3) Japan Hydrographic Association, Tsukiji, Tokyo, Japan 4) Marine Information Science, 11th Japan Coast Guard, Naha, Okinawa, Japan 5) Department of Ocean Civil Engineering, Kagoshima University, 1-21-40 Korimoto, Kagoshima, Japan 6) IO Technic, 2-28-19 Minami, Tsukushino, Machida, Tokyo, Japan Abstract. In 2004 and 2005, five drowning accidents in Ishigakijima, Okinawa were documented by Japan Coast Guard and were found to be caused by a strong offshore current commonly known as “reef current”. This type of current has been identified to be responsible in generating the circulation of water and transportation of sediment in coral reefs. In this paper, however, high-speed offshore current in coral reefs is specifically referred to as “reef rip current”. Considering that the generation mechanism of reef rip current is not revealed yet, the researchers conducted a hydrodynamic study in Yoshiwara Coast, Ishigakijima, Okinawa in two phases (normal and storm conditions) during summer season to determine the location and time of occurrence of the strong offshore current that will significantly address safe utilization of coral reef and carbonate beach thereby reducing drowning accidents.