Planktonic Subsidies to Surf-Zone and Intertidal Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Observations of Nearshore Infragravity Waves: Seaward and Shoreward Propagating Components A

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 107, NO. C8, 3095, 10.1029/2001JC000970, 2002 Observations of nearshore infragravity waves: Seaward and shoreward propagating components A. Sheremet,1 R. T. Guza,2 S. Elgar,3 and T. H. C. Herbers4 Received 14 May 2001; revised 5 December 2001; accepted 20 December 2001; published 6 August 2002. [1] The variation of seaward and shoreward infragravity energy fluxes across the shoaling and surf zones of a gently sloping sandy beach is estimated from field observations and related to forcing by groups of sea and swell, dissipation, and shoreline reflection. Data from collocated pressure and velocity sensors deployed between 1 and 6 m water depth are combined, using the assumption of cross-shore propagation, to decompose the infragravity wave field into shoreward and seaward propagating components. Seaward of the surf zone, shoreward propagating infragravity waves are amplified by nonlinear interactions with groups of sea and swell, and the shoreward infragravity energy flux increases in the onshore direction. In the surf zone, nonlinear phase coupling between infragravity waves and groups of sea and swell decreases, as does the shoreward infragravity energy flux, consistent with the cessation of nonlinear forcing and the increased importance of infragravity wave dissipation. Seaward propagating infragravity waves are not phase coupled to incident wave groups, and their energy levels suggest strong infragravity wave reflection near the shoreline. The cross-shore variation of the seaward energy flux is weaker than that of the shoreward flux, resulting in cross-shore variation of the squared infragravity reflection coefficient (ratio of seaward to shoreward energy flux) between about 0.4 and 1.5. -

INTERTIDAL ZONATION Introduction to Oceanography Spring 2017 The

INTERTIDAL ZONATION Introduction to Oceanography Spring 2017 The Intertidal Zone is the narrow belt along the shoreline lying between the lowest and highest tide marks. The intertidal or littoral zone is subdivided broadly into four vertical zones based on the amount of time the zone is submerged. From highest to lowest, they are Supratidal or Spray Zone Upper Intertidal submergence time Middle Intertidal Littoral Zone influenced by tides Lower Intertidal Subtidal Sublittoral Zone permanently submerged The intertidal zone may also be subdivided on the basis of the vertical distribution of the species that dominate a particular zone. However, zone divisions should, in most cases, be regarded as approximate! No single system of subdivision gives perfectly consistent results everywhere. Please refer to the intertidal zonation scheme given in the attached table (last page). Zonal Distribution of organisms is controlled by PHYSICAL factors (which set the UPPER limit of each zone): 1) tidal range 2) wave exposure or the degree of sheltering from surf 3) type of substrate, e.g., sand, cobble, rock 4) relative time exposed to air (controls overheating, desiccation, and salinity changes). BIOLOGICAL factors (which set the LOWER limit of each zone): 1) predation 2) competition for space 3) adaptation to biological or physical factors of the environment Species dominance patterns change abruptly in response to physical and/or biological factors. For example, tide pools provide permanently submerged areas in higher tidal zones; overhangs provide shaded areas of lower temperature; protected crevices provide permanently moist areas. Such subhabitats within a zone can contain quite different organisms from those typical for the zone. -

Rip Current Observations Via Marine Radar

Rip Current Observations via Marine Radar Merrick C. Haller, M.ASCE1; David Honegger2; and Patricio A. Catalan3 Abstract: New remote sensing observations that demonstrate the presence of rip current plumes in X-band radar images are presented. The observations collected on the Outer Banks (Duck, North Carolina) show a regular sequence of low-tide, low-energy, morphologically driven rip currents over a 10-day period. The remote sensing data were corroborated by in situ current measurements that showed depth-averaged rip current velocities were 20e40 cm=s whereas significant wave heights were Hs 5 0:5e1 m. Somewhat surprisingly, these low-energy rips have a surface signature that sometimes extends several surf zone widths from shore and persists for periods of several hours, which is in contrast with recent rip current observations obtained with Lagrangian drifters. These remote sensing observations provide a more synoptic picture of the rip current flow field and allow the identification of several rip events that were not captured by the in situ sensors and times of alongshore deflection of the rip flow outside the surf zone. These data also contain a rip outbreak event where four separate rips were imaged over a 1-km stretch of coast. For potential comparisons of the rip current signature across other radar platforms, an example of a simply calibrated radar image is also given. Finally, in situ observations of the vertical structure of the rip current flow are given, and a threshold offshore wind stress (.0:02 m=s2)isfoundto preclude the rip current imaging. DOI: 10.1061/(ASCE)WW.1943-5460.0000229. -

Animal Adaptations

Animal Adaptations The Animal Adaptations program at Hatfield Marine Science Center is designed to be a 50- minute lab-based program for 3rd-12th grade students that examines marine organisms from three different habitats (sandy beach, rocky shore and estuary) and explores the many ways they are adapted to their particular environment. This lab focuses on the adaptations of several groups of marine animals including Mollusks, Crustaceans, and Echinoderms, and investigates how they differ depending on whether they are found in a sandy beach, rocky shore, or estuary environment. Students will work in small groups with a variety of live animals, studying individual characteristics and how these organisms interact with their environment and one another. Background Information The Oregon Coast is made up of a series of rocky shores, sandy beaches, and estuaries, all of which are greatly affected by fluctuating tides. Many of these areas are intertidal and are alternately inundated by seawater and exposed to air, wind, and dramatic changes in temperature and salinity. High tide floods these areas with cold, nutrient laden seawater, bringing food to organisms that live there in the form of plankton and detritus. Low tides often expose these organisms to the dangers of predation and desiccation. In addition to tidal effects, organisms that inhabit sandy beaches and rocky shores also have to deal with the physical stresses of pounding waves. Because of these harsh conditions, organisms have developed special adaptations that not only help them to survive but thrive in these environments. An adaptation is a physical or behavioral trait that helps a plant or animal survive in a specific environment or habitat. -

Seashore the SANDYSEASHORE the Soilisinfertile, Anditisoften Windy, Andsalty

SEASHORE DESCRIPTION The seashore is an area fi lled with an interesting mix of unique plants and animals that have adapted to cope with this environment. Living on the edge of the sea is not easy. The soil is infertile, and it is often windy, dry and salty. THE SANDY SEASHORE Along a sandy shore there are no large rocks, algae or tidal pools. The sandy seashore can be divided into four general zones: Intertidal, Pioneer, Fixed Dune and Scrub Woodland. 1. Intertidal Zone: Between the low tide and the high tide mark is the intertidal zone. When the tide goes out the creatures living in this zone are left stranded. They have to endure the heat of the sun and the higher salinity of the water resulting from evaporation. Notice the many small holes on a sandy beach; they are the doorways to the homes of many animals which burrow under the sand where it is cooler. Some of Ecosystems of The Bahamas the creatures living in this zone are sea worms, sand fl eas and sand crabs. 2. Pioneer Zone: So named because it is where the fi rst plants to try to grow over sand. These plants must adapt to loose, shifting sand and poor soil. There is no protection from wind or salt spray. Plants here are usually low growing vines with waxy leaves. Some plants found in the pioneer zone are Purple seaside bean (C. rosea), Saltwort (Batis maritima), Goat's foot (Ipomea pes-caprae), and Sea purslane (Sesuvium portulacastrum). 3. Fixed Dune Zone: The next zone is the fi xed dune, so named because as the plants in the pioneer zone grip the sand around their roots and make the beach more stable, the sand mounds up into small humps or dunes. -

Mapping Turbidity Currents Using Seismic Oceanography Title Page Abstract Introduction 1 2 E

Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Ocean Sci. Discuss., 8, 1803–1818, 2011 www.ocean-sci-discuss.net/8/1803/2011/ Ocean Science doi:10.5194/osd-8-1803-2011 Discussions OSD © Author(s) 2011. CC Attribution 3.0 License. 8, 1803–1818, 2011 This discussion paper is/has been under review for the journal Ocean Science (OS). Mapping turbidity Please refer to the corresponding final paper in OS if available. currents using seismic E. A. Vsemirnova and R. W. Hobbs Mapping turbidity currents using seismic oceanography Title Page Abstract Introduction 1 2 E. A. Vsemirnova and R. W. Hobbs Conclusions References 1Geospatial Research Ltd, Department of Earth Sciences, Tables Figures Durham University, Durham DH1 3LE, UK 2Department of Earth Sciences, Durham University, Durham DH1 3LE, UK J I Received: 25 May 2011 – Accepted: 12 August 2011 – Published: 18 August 2011 J I Correspondence to: R. W. Hobbs ([email protected]) Published by Copernicus Publications on behalf of the European Geosciences Union. Back Close Full Screen / Esc Printer-friendly Version Interactive Discussion 1803 Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Discussion Paper | Abstract OSD Using a combination of seismic oceanographic and physical oceanographic data ac- quired across the Faroe-Shetland Channel we present evidence of a turbidity current 8, 1803–1818, 2011 that transports suspended sediment along the western boundary of the Channel. We 5 focus on reflections observed on seismic data close to the sea-bed on the Faroese Mapping turbidity side of the Channel below 900m. Forward modelling based on independent physi- currents using cal oceanographic data show that thermohaline structure does not explain these near seismic sea-bed reflections but they are consistent with optical backscatter data, dry matter concentrations from water samples and from seabed sediment traps. -

Save the Reef

Save the Reef A member group of Lock the Gate Alliance www.savethereef.net.au Committee Secretary Senate Standing Committees on Environment and Communications PO Box 6100 Parliament House Canberra ACT 2600 Phone: +61 2 6277 3526 Fax: +61 2 6277 5818 [email protected] Submission to the Senate Inquiry on The adequacy of the Australian and Queensland Governments’ efforts to stop the rapid decline of the Great Barrier Reef, including but not limited to: Points a–k. Save the Reef would like to thank this committee for the opportunity to make a submission and would also like to speak further if there is an opportunity at any public hearings. The Great Barrier Reef is Australia’s greatest natural asset. It is a tourism mecca, a 6 billion dollar economic boon as well as a scientific wonderland. It is a World Heritage Listed property and an acknowledged world wonder. The Great Barrier Reef is part of Australia’s very identity. We are failing to protect the Great Barrier Reef. The efforts to stop the rapid decline of the Great Barrier Reef are grossly inadequate. It demonstrates that our current system for protecting the environment is broken. Environmental impact statements, conditions, offsets, regulations, enforcement and even the EPBC act, processes meant to protect the environment are being subverted and the impact is apparent. The holes in the “Swiss Cheese” are lining up and have allowed and are continuing to allow further destruction of the Great Barrier Reef when it needs our protection the most. The recent developments in Gladstone are a clear demonstration of the failure of our systems. -

PROTISTS Shore and the Waves Are Large, Often the Largest of a Storm Event, and with a Long Period

(seas), and these waves can mobilize boulders. During this phase of the storm the rapid changes in current direction caused by these large, short-period waves generate high accelerative forces, and it is these forces that ultimately can move even large boulders. Traditionally, most rocky-intertidal ecological stud- ies have been conducted on rocky platforms where the substrate is composed of stable basement rock. Projec- tiles tend to be uncommon in these types of habitats, and damage from projectiles is usually light. Perhaps for this reason the role of projectiles in intertidal ecology has received little attention. Boulder-fi eld intertidal zones are as common as, if not more common than, rock plat- forms. In boulder fi elds, projectiles are abundant, and the evidence of damage due to projectiles is obvious. Here projectiles may be one of the most important defi ning physical forces in the habitat. SEE ALSO THE FOLLOWING ARTICLES Geology, Coastal / Habitat Alteration / Hydrodynamic Forces / Wave Exposure FURTHER READING Carstens. T. 1968. Wave forces on boundaries and submerged bodies. Sarsia FIGURE 6 The intertidal zone on the north side of Cape Blanco, 34: 37–60. Oregon. The large, smooth boulders are made of serpentine, while Dayton, P. K. 1971. Competition, disturbance, and community organi- the surrounding rock from which the intertidal platform is formed zation: the provision and subsequent utilization of space in a rocky is sandstone. The smooth boulders are from a source outside the intertidal community. Ecological Monographs 45: 137–159. intertidal zone and were carried into the intertidal zone by waves. Levin, S. A., and R. -

Sample Chapter Algal Blooms

ALGAL BLOOMS 7 Observations and Remote Sensing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1109/ energy and material transport through the food web, and JSTARS.2013.2265255. they also play an important role in the vertical flux of Pack, R. T., Brooks, V., Young, J., Vilaca, N., Vatslid, S., Rindle, P., material out of the surface waters. These blooms are Kurz, S., Parrish, C. E., Craig, R., and Smith, P. W., 2012. An “ ” overview of ALS technology. In Renslow, M. S. (ed.), Manual distinguished from those that are deemed harmful. of Airborne Topographic Lidar. Bethesda: ASPRS Press. Algae form harmful algal blooms, or HABs, when either Sithole, G., and Vosselman, G., 2004. Experimental comparison of they accumulate in massive amounts that alone cause filter algorithms for bare-Earth extraction from airborne laser harm to the ecosystem or the composition of the algal scanning point clouds. ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and community shifts to species that make compounds Remote Sensing, 59,85–101. (including toxins) that disrupt the normal food web or to Shan, J., and Toth, C., 2009. Topographic Laser Ranging and Scanning: Principles and Processes. Boca Raton: CRC Press. species that can harm human consumers (Glibert and Slatton, K. C., Carter, W. E., Shrestha, R. L., and Dietrich, W., 2007. Pitcher, 2001). HABs are a broad and pervasive problem, Airborne laser swath mapping: achieving the resolution and affecting estuaries, coasts, and freshwaters throughout the accuracy required for geosurficial research. Geophysical world, with effects on ecosystems and human health, and Research Letters, 34,1–5. on economies, when these events occur. This entry Wehr, A., and Lohr, U., 1999. -

Infragravity Wave Energy Partitioning in the Surf Zone in Response to Wind-Sea and Swell Forcing

Journal of Marine Science and Engineering Article Infragravity Wave Energy Partitioning in the Surf Zone in Response to Wind-Sea and Swell Forcing Stephanie Contardo 1,*, Graham Symonds 2, Laura E. Segura 3, Ryan J. Lowe 4 and Jeff E. Hansen 2 1 CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere, Crawley 6009, Australia 2 Faculty of Science, School of Earth Sciences, The University of Western Australia, Crawley 6009, Australia; [email protected] (G.S.); jeff[email protected] (J.E.H.) 3 Departamento de Física, Universidad Nacional, Heredia 3000, Costa Rica; [email protected] 4 Faculty of Engineering and Mathematical Sciences, Oceans Graduate School, The University of Western Australia, Crawley 6009, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 18 September 2019; Accepted: 23 October 2019; Published: 28 October 2019 Abstract: An alongshore array of pressure sensors and a cross-shore array of current velocity and pressure sensors were deployed on a barred beach in southwestern Australia to estimate the relative response of edge waves and leaky waves to variable incident wind wave conditions. The strong sea 1 breeze cycle at the study site (wind speeds frequently > 10 m s− ) produced diurnal variations in the peak frequency of the incident waves, with wind sea conditions (periods 2 to 8 s) dominating during the peak of the sea breeze and swell (periods 8 to 20 s) dominating during times of low wind. We observed that edge wave modes and their frequency distribution varied with the frequency of the short-wave forcing (swell or wind-sea) and edge waves were more energetic than leaky waves for the duration of the 10-day experiment. -

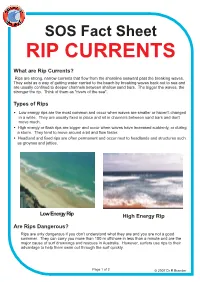

What Are Rip Currents? Types of Rips Are Rips Dangerous

What are Rip Currents? Rips are strong, narrow currents that flow from the shoreline seaward past the breaking waves. They exist as a way of getting water carried to the beach by breaking waves back out to sea and are usually confined to deeper channels between shallow sand bars. The bigger the waves, the stronger the rip. Think of them as "rivers of the sea". Types of Rips • Low energy rips are the most common and occur when waves are smaller or haven't changed in a while. They are usually fixed in place and sit in channels between sand bars and don't move much. • High energy or flash rips are bigger and occur when waves have increased suddenly, or during a storm. They tend to move around a bit and flow faster. • Headland and fixed rips are often permanent and occur next to headlands and structures such as groynes and jetties. Low Energy Rip High Energy Rip Are Rips Dangerous? Rips are only dangerous if you don't understand what they are and you are not a good swimmer. They can carry you more than 100 m offshore in less than a minute and are the major cause of surf drownings and rescues in Australia. However, surfers use rips to their advantage to help them swim out through the surf quickly. Page1of2 © 2007 Dr R Brander continued Spotting a Rip Since rips often sit in deeper channels between shallow sand bars, always spend 5-10 minutes looking at the surf zone for consistent darker and "calmer" areas of water that extend offshore between the breaking waves. -

Impacts of Climate Change on the Occurrence of Harmful Algal Blooms

Office of Water EPA 820-S-13-001 MC 4304T May 2013 Impacts of Climate Change on the Occurrence of Harmful Algal Blooms Summary Background Climate change is predicted to change many Algae occur naturally in marine and fresh waters. environmental conditions that could affect the Under favorable conditions that include adequate natural properties of fresh and marine waters both in light availability, warm waters, and high nutrient the US and worldwide. Changes in these factors levels, algae can rapidly grow and multiply causing could favor the growth of harmful algal blooms and “blooms.” Blooms of algae can cause damage to habitat changes such that marine HABs can invade aquatic environments by blocking sunlight and and occur in freshwater. An increase in the depleting oxygen required by other aquatic occurrence and intensity of harmful algal blooms organisms, restricting their growth and survival. may negatively impact the environment, human Some species of algae, including golden and red health, and the economy for communities across the algae and certain types of cyanobacteria, can produce US and around the world. The purpose of this fact potent toxins that can cause adverse health effects to sheet is to provide climate change researchers and wildlife and humans, such as damage to the liver and decision–makers a summary of the potential impacts nervous system. When algal blooms impair aquatic of climate change on harmful algal blooms in ecosystems or have the potential to affect human freshwater and marine ecosystems. Although much health, they are known as harmful algal blooms of the evidence presented in this fact sheet suggests (HABs).