Parliamentary System and Framing of the 1973 Constitution: Contest Between Government and Opposition Inside the National Assembly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Curriculum of Pakistan Studies Bs

CURRICULUM OF PAKISTAN STUDIES BS 2008 HIGHER EDUCATION COMMISSION ISLAMABAD. 1 CURRICULUM DIVISION, HEC Dr. Syed Sohail H. Naqvi Executive Director Prof. Dr. Riaz ul Haq Tariq Member (Acad) Miss Ghayyur Fatima Deputy Director (Curri) Mr. M. Tahir Ali Shah Assistant Director Mr. Shafiullah Khan Assistant Director 2 Table of Content 1. Introduction 2. Scheme of Studies for BS (4-Year) in Pakistan Studies 3. Details of Courses for BS (4-Year) in Pakistan Studies a) Foundation Courses b) Major and Elective Courses 4. Annexure – C, D, E & F. 3 PREFACE Curriculum development is a highly organized and systematic process and involves a number of procedures. Many of these procedures include incorporating the results from international research studies and reforms made in other countries. These studies and reforms are then related to the particular subject and the position in Pakistan so that the proposed curriculum may have its roots in the socio- economics setup in which it is to be introduced. Hence, unlike a machine, it is not possible to accept any curriculum in its entirety. It has to be studied thoroughly and all aspects are to be critically examined before any component is recommended for adoption. In exercise of the powers conferred by sub-section (1) of section 3 of the Federal Supervision of Curricula Textbooks and Maintenance of Standards of Education Act 1976, the Federal Government vide notification No. D773/76-JEA (cur.), dated December 4th 1976, appointed the University Grants Commission as the competent authority to look after the curriculum revision work beyond class XII at the bachelor level and onwards to all degrees, certificates and diplomas awarded by degree colleges, universities and other institutions of higher education. -

Alternative Narratives for Preventing the Radicalization of Muslim Youth By

Spring /15 Nr. 2 ISSN: 2363-9849 Alternative Narratives for Preventing the Radicalization of Muslim Youth By: Dr. Afzal Upal 1 Introduction The international jihadist movement has declared war. They have declared war on anybody who does not think and act exactly as they wish they would think and act. We may not like this and wish it would go away, but it’s not going to go away, and the reality is we are going to have to confront it. (Prime Minister Steven Harper, 8 Jan 2015) With an increasing number of Western Muslims falling prey to violent extremist ideologies and joining Jihadi organizations such as Al-Qaida and the ISIS, Western policy makers have been concerned with preventing radicalization of Muslim youth. This has resulted in a number of government sponsored efforts (e.g., MyJihad, Sabahi, and Maghrebia (Briggs and Feve 2013)) to counter extremist propaganda by arguing that extremist violent tactics used by Jihadist organizations are not congruent with Islamic tenets of kindness and just war. Despite the expenditure of significant resources since 2001, these efforts have had limited success. This article argues that in order to succeed we need to better understand Muslim core social identity beliefs (i.e., their perception of what it means to be a good Muslim) and how these beliefs are connected to Muslims perceptions of Westerners. A better understanding of the interdependent nature and dynamics of these beliefs will allow us to design counter radicalization strategies that have a better chance of success. 1 Dr. M Afzal Upal is a cognitive scientist of religion with expertise in the Islamic social and religious movements. -

Political Development, the People's Party of Pakistan and the Elections of 1970

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1973 Political development, the People's Party of Pakistan and the elections of 1970. Meenakshi Gopinath University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Gopinath, Meenakshi, "Political development, the People's Party of Pakistan and the elections of 1970." (1973). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2461. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/2461 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FIVE COLLEGE DEPOSITORY POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT, THE PEOPLE'S PARTY OF PAKISTAN AND THE ELECTIONS OF 1970 A Thesis Presented By Meenakshi Gopinath Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS June 1973 Political Science POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT, THE PEOPLE'S PARTY OF PAKISTAN AND THE ELECTIONS OF 1970 A Thesis Presented By Meenakshi Gopinath Approved as to style and content hy: Prof. Anwar Syed (Chairman of Committee) f. Glen Gordon (Head of Department) Prof. Fred A. Kramer (Member) June 1973 ACKNOWLEDGMENT My deepest gratitude is extended to my adviser, Professor Anwar Syed, who initiated in me an interest in Pakistani poli- tics. Working with such a dedicated educator and academician was, for me, a totally enriching experience. I wish to ex- press my sincere appreciation for his invaluable suggestions, understanding and encouragement and for synthesizing so beautifully the roles of Friend, Philosopher and Guide. -

Conflict Between India and Pakistan Roots of Modern Conflict

Conflict between India and Pakistan Roots of Modern Conflict Conflict between India and Pakistan Peter Lyon Conflict in Afghanistan Ludwig W. Adamec and Frank A. Clements Conflict in the Former Yugoslavia John B. Allcock, Marko Milivojevic, and John J. Horton, editors Conflict in Korea James E. Hoare and Susan Pares Conflict in Northern Ireland Sydney Elliott and W. D. Flackes Conflict between India and Pakistan An Encyclopedia Peter Lyon Santa Barbara, California Denver, Colorado Oxford, England Copyright 2008 by ABC-CLIO, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lyon, Peter, 1934– Conflict between India and Pakistan : an encyclopedia / Peter Lyon. p. cm. — (Roots of modern conflict) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-57607-712-2 (hard copy : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-57607-713-9 (ebook) 1. India—Foreign relations—Pakistan—Encyclopedias. 2. Pakistan-Foreign relations— India—Encyclopedias. 3. India—Politics and government—Encyclopedias. 4. Pakistan— Politics and government—Encyclopedias. I. Title. DS450.P18L86 2008 954.04-dc22 2008022193 12 11 10 9 8 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Production Editor: Anna A. Moore Production Manager: Don Schmidt Media Editor: Jason Kniser Media Resources Manager: Caroline Price File Management Coordinator: Paula Gerard This book is also available on the World Wide Web as an eBook. -

Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India

Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India Gyanendra Pandey CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Remembering Partition Violence, Nationalism and History in India Through an investigation of the violence that marked the partition of British India in 1947, this book analyses questions of history and mem- ory, the nationalisation of populations and their pasts, and the ways in which violent events are remembered (or forgotten) in order to en- sure the unity of the collective subject – community or nation. Stressing the continuous entanglement of ‘event’ and ‘interpretation’, the author emphasises both the enormity of the violence of 1947 and its shifting meanings and contours. The book provides a sustained critique of the procedures of history-writing and nationalist myth-making on the ques- tion of violence, and examines how local forms of sociality are consti- tuted and reconstituted by the experience and representation of violent events. It concludes with a comment on the different kinds of political community that may still be imagined even in the wake of Partition and events like it. GYANENDRA PANDEY is Professor of Anthropology and History at Johns Hopkins University. He was a founder member of the Subaltern Studies group and is the author of many publications including The Con- struction of Communalism in Colonial North India (1990) and, as editor, Hindus and Others: the Question of Identity in India Today (1993). This page intentionally left blank Contemporary South Asia 7 Editorial board Jan Breman, G.P. Hawthorn, Ayesha Jalal, Patricia Jeffery, Atul Kohli Contemporary South Asia has been established to publish books on the politics, society and culture of South Asia since 1947. -

Son of the Desert

Dedicated to Mohtarma Benazir Bhutto Shaheed without words to express anything. The Author SONiDESERT A biography of Quaid·a·Awam SHAHEED ZULFIKAR ALI H By DR. HABIBULLAH SIDDIQUI Copyright (C) 2010 by nAfllST Printed and bound in Pakistan by publication unit of nAfllST Shaheed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto/Shaheed Benazir Bhutto Archives. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. First Edition: April 2010 Title Design: Khuda Bux Abro Price Rs. 650/· Published by: Shaheed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto/ Shaheed Benazir Bhutto Archives 4.i. Aoor, Sheikh Sultan Trust, Building No.2, Beaumont Road, Karachi. Phone: 021-35218095-96 Fax: 021-99206251 Printed at: The Time Press {Pvt.) Ltd. Karachi-Pakistan. CQNTENTS Foreword 1 Chapter: 01. On the Sands of Time 4 02. The Root.s 13 03. The Political Heritage-I: General Perspective 27 04. The Political Heritage-II: Sindh-Bhutto legacy 34 05. A revolutionary in the making 47 06. The Life of Politics: Insight and Vision· 65 07. Fall out with the Field Marshal and founding of Pakistan People's Party 108 08. The state dismembered: Who is to blame 118 09. The Revolutionary in the saddle: New Pakistan and the People's Government 148 10. Flash point.s and the fallout 180 11. Coup d'etat: tribulation and steadfasmess 197 12. Inside Death Cell and out to gallows 220 13. Home they brought the warrior dead 229 14. -

Federal Urdu University of Arts, Sciences & Technology

Degree Year Of Student Selection Campus Department Title Study Full Name Father Name CNIC Degree Title CGPA Status Merit Status Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 Khizra Khalil Khalil Ahmed Bajwa 6110152362736 BS (Hons) 3.2 Selected Student Eligible Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 ANAM ZHARA SYED AKHTER HUSSAIN SHAH 3740319867784 BS (Hons) 3.3 Selected Student Eligible Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 masood ur rehman Rehan shah 2140792271819 BS (Hons) 3.16 Selected Student Eligible Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 Muhammad Irfan Allah Dewaya 3220336130281 BS (Hons) 3.6 Selected Student Eligible Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 Ahsan Iftikhar Iftikhar Ahmad 3720114487337 BS (Hons) 3.58 Selected Student Eligible Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 Qurat Ul Ain Aziz Ullah Khan 3830101789040 BS (Hons) 3.18 Selected Student Eligible Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 Muhammad Majid Muhammad Faridoon 3740589951603 BS (Hons) 3.51 Selected Student Eligible Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 Abdul Manan Muhammad Saleem 3740341694235 BS (Hons) 3.88 Selected Student Eligible Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 Muhammad Awais Muhammad Saeed 3710293250617 BS (Hons) 3.55 Selected Student Eligible Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 MAYA SYED SYED TAFAZUL HASSAN 6110194455878 BS (Hons) 3.7 Selected Student Eligible Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 Mehreen Bibi Faqar Din 8220209594876 BS (Hons) 3.2 Selected Student Eligible Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 AMBREEN SAFDAR MALIK SAFDAR HUSSAIN 6110192701214 -

Pak-Us Strategic Partnership Amidst Conflicting Approaches Towards Militancy (2005-2015)

PAK-US STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIP AMIDST CONFLICTING APPROACHES TOWARDS MILITANCY (2005-2015) ASIF SALIM Ph.D (Scholar) DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE UNIVERSITY OF PESHAWAR SESSION: 2014-15 PAK-US STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIP AMIDST CONFLICTING APPROACHES TOWARDS MILITANCY (2005-2015) Thesis submitted to the Department of Political Science, University of Peshawar, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE MARCH, 2018 i ABSTRACT International system based on anarchic theories and approaches in which power politics and statism are the basic components which play vital role when states conduct the relations with one another. The power of the state can be appraised through its ability to protect its national interests at any cost. States in relation with equal strength can easily protect their national interests but when the small and big state interests are clashed with each other, double standers and distrust take birth. Pakistan and the US relation is the best example of the realistic ideas in which it can be safely quoted „There is no permanent friendship and enmity. There are interests that decide the faith of friendship and enmity‟. After the partition of subcontinent civil and military leadership deviated from the golden principles of the founder (Quaid-e-Azam Muhammad Ali Jinnah) and joined the western bloc. America warmly welcomed Pakistan as the US needed partner in South and Southwest Asia and Asia Pacific to counter the spread of communistic ideologies in the region. From the day one the leader ship of Pakistan was not concerned with the communism but interested to acquire economic and military assistance from the US so as to keep balance with India. -

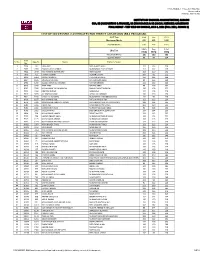

Announced on Monday, July 19, 2021

FINAL RESULT - FALL 2021 ROUND 2 Announced on Monday, July 19, 2021 INSTITUTE OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, KARACHI BBA, BS (ACCOUNTING & FINANCE), BS (ECONOMICS) & BS (SOCIAL SCIENCES) ADMISSIONS FINAL RESULT ‐ TEST HELD ON SUNDAY, JULY 4, 2021 (FALL 2021, ROUND 2) LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES FOR DIRECT ADMISSION (BBA PROGRAM) SAT Test Math Eng TOTAL Maximum Marks 800 800 1600 Cut-Off Marks 600 600 1420 Math Eng Total IBA Test MCQ MCQ MCQ Maximum Marks 180 180 360 Cut-Off Marks 88 88 224 Seat S. No. App No. Name Father's Name No. 1 7904 30 LAIBA RAZI RAZI AHMED JALALI 112 116 228 2 7957 2959 HASSAAN RAZA CHINOY MUHAMMAD RAZA CHINOY 112 132 244 3 7962 3549 MUHAMMAD SHAYAN ARIF ARIF HUSSAIN 152 120 272 4 7979 455 FATIMA RIZWAN RIZWAN SATTAR 160 92 252 5 8000 1464 MOOSA SHERGILL FARZAND SHERGILL 124 124 248 6 8937 1195 ANAUSHEY BATOOL ATTA HUSSAIN SHAH 92 156 248 7 8938 1200 BIZZAL FARHAN ALI MEMON FARHAN MEMON 112 112 224 8 8978 2248 AFRA ABRO NAVEED ABRO 96 136 232 9 8982 2306 MUHAMMAD TALHA MEMON SHAHID PARVEZ MEMON 136 136 272 10 9003 3266 NIRDOSH KUMAR NARAIN NA 120 108 228 11 9017 3635 ALI SHAZ KARMANI IMTIAZ ALI KARMANI 136 100 236 12 9031 1945 SAIFULLAH SOOMRO MUHAMMAD IBRAHIM SOOMRO 132 96 228 13 9469 1187 MUHAMMAD ADIL RAFIQ AHMAD KHAN 112 112 224 14 9579 2321 MOHAMMAD ABDULLAH KUNDI MOHAMMAD ASGHAR KHAN KUNDI 100 124 224 15 9582 2346 ADINA ASIF MALIK MOHAMMAD ASIF 104 120 224 16 9586 2566 SAMAMA BIN ASAD MUHAMMAD ASAD IQBAL 96 128 224 17 9598 2685 SYED ZAFAR ALI SYED SHAUKAT HUSSAIN SHAH 124 104 228 18 9684 526 MUHAMMAD HAMZA -

SUHAIL-THESIS.Pdf (347.6Kb)

Copyright by Adeem Suhail 2010 The Thesis committee for Adeem Suhail Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: The Pakistan National Alliance of 1977 APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: ________________________________________ (Syed Akbar Hyder) __________________________________________ (Kamran Asdar Ali) The Pakistan National Alliance of 1977 by Adeem Suhail, BA; BSEE Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2011 The Pakistan National Alliance of 1977 by Adeem Suhail, MA The University of Texas at Austin, 2011 SUPERVISOR: Syed Akbar Hyder Abstract This study focuses on the Pakistan National Alliance (PNA) and the movement associated with that party, in the aftermath of the 1977 elections in Pakistan. Through this study, the author addresses the issue of regionalism and its effects on politics at a National level. A study of the course of the movement also allows one to look at the problems in representation and how ideological stances merge with material conditions and needs of the country’s citizenry to articulate the desire for, what is basically, an equitable form of democracy that is peculiar to Pakistan. The form of such a democratic system of governance can be gauged through the frustrations and desires of the variety of Pakistan’s oppressed classes. Moreover, the fissures within the discourses that appear through the PNA, as well as their reassessment and analysis helps one formulate a fresh conception of resistance along different matrices of society within the country. -

Distilling Eligibility and Virtue: Articles 62 and 63 of the Pakistani Constitution

Distilling Eligibility and Virtue Distilling Eligibility and Virtue: Articles 62 and 63 of the Pakistani Constitution Saad Rasool* This article analyses the provisions regarding the qualifications and disqualifications for Parliamentarians set out in the constitution of Pakistan, and traces their evolution over the years. It establishes that the objective interpretation of these provisions in the past has given way to a more subjective and moralistic approach in the run-up to the 2013 general elections. It further argues that, for the most part, these provisions lay down unascertainable and subjective criteria for qualification and disqualification of a Parliamentarian. This in turn lends support to the main argument of this article that the fundamental right of an individual to contest for a public office, and an equal fundamental right of the citizenry to choose their representative cannot be refused, on the grounds of such ambiguous ideas. However, this is not to say that there should be no minimum criteria for qualifying to be a Parliamentarian; rather it is suggested that the present criteria suffer from serious defects which need to be remedied. Introduction The endeavour of law, in a democratic dispensation, is that of creating an ideal society – a society that is not simply a reflection of who we are, but, more importantly, of who we aspire to be. This endeavour, reflected in the corpus of our laws, emanates primarily from the legislature – the arm of the state that is entrusted with shaping the laws and freedoms that define the spirit of our society. In fidelity to the democratic ethos of a * Lawyer based in Lahore, and Visiting Faculty at LUMS. -

The Pakistan National Bibliography 1999

THE PAKISTAN NATIONAL BIBLIOGRAPHY 1999 A Subject Catalogue of the new Pakistani books deposited under the provisions of Copyright Law or acquired through purchase, etc. by the National Library of Pakistan, Islamabad, arranged according to the Dewey Decimal Classification, 20th edition and catalogued according to the Anglo American Cataloguing Rules, 2nd revised edition, 1988, with a full Author, Title, Subject Index and List of Publishers. Government of Pakistan, Department of Libraries National Library of Pakistan Constitution Avenue, Islamabad 2000 © Department of Libraries (National Bibliographical Unit) ⎯ 2000. ISSN 10190678 ISBN 969-8014-31-4 Price: Within Pakistan……..Rs. 1100.00 Outside Pakistan…….US$ 60.00 Available from: National Book Foundation, 6-Mauve Area, Taleemi Chowk, Sector G-8/4, ISLAMABAD P A K I S T A N. (ii) PREFACE The objects of the Pakistan National Bibliography are to list new works published in Pakistan, to describe each work in detail and to give the subject matter of each work as precisely as possible. The 1999 volume of the Pakistan National Bibliography covers Pakistani publications published during the year 1999 and received in the Delivery of Books and Newspapers Branch of the National Library of Pakistan at Islamabad under the Provisions of Copyright Law: Copy right Ordinance, 1962 as amended by Copyright (Amendment) Act, 1973 & 1992. Those titles which were not received under the Copyright Law but were acquired through purchase, gift and exchange have also been included in the Bibliography. Every endeavour has been made to ensure the accuracy of the information given. The following classes of publications have been excluded: a) The keys and guides to text-books and ephemeral material such as publicity pamphlets etc.