The Mirage of Power, by Mubashir Hasan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phd, MS/Mphil BS/Bsc (Hons) 2021-22 GCU

PhD, MS/MPhil BS/BSc (Hons) GCU GCU To Welcome 2021-22 A forward-looking institution committed to generating and disseminating cutting- GCUedge knowledge! Our vision is to provide students with the best educational opportunities and resources to thrive on and excel in their careers as well as in shaping the future. We believe that courage and integrity in the pursuit of knowledge have the power to influence and transform the world. Khayaali Production Government College University Press All Rights Reserved Disclaimer Any part of this prospectus shall not be reproduced in any form or by any means without permission from Government CONTENTS College University Press Lahore. University Rules, Regulations, Policies, Courses of Study, Subject Combinations and University Dues etc., mentioned in this Prospectus may be withdrawn or amended by the University authorities at any time without any notice. The students shall have to follow the amended or revised Rules, Regulations, Policies, Syllabi, Subject Combinations and pay University Dues. Welcome To GCU 2 Department of History 198 Vice Chancellor’s Message 6 Department of Management Studies 206 Our Historic Old Campus 8 Department of Philosophy and Interdisciplinary Studies 214 GCU’s New Campus 10 Department of Political Science 222 Department of Sociology 232 (Located at Kala Shah Kaku) 10 Journey from Government College to Government College Faculty of Languages, Islamic and Oriental Learning University, Lahore 12 Department of Arabic and Islamic Studies 242 Legendary Alumni 13 Department of -

Muslim Nationalism, State Formation and Legal Representations of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan

Politics of Exclusion: Muslim Nationalism, State Formation and Legal Representations of the Ahmadiyya Community in Pakistan by Sadia Saeed A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Sociology) in The University of Michigan 2010 Doctoral Committee: Professor George P. Steinmetz, Chair Professor Howard A. Kimeldorf Associate Professor Fatma Muge Gocek Associate Professor Genevieve Zubrzycki Professor Mamadou Diouf, Columbia University © Sadia Saeed 2010 2 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my parents with my deepest love, respect and gratitude for the innumerable ways they have supported my work and choices. ii Acknowledgements I would like to begin by acknowledging the immense support my parents have given me every step of the way during my (near) decade in graduate school. I have dedicated this dissertation to them. My ammi and baba have always believed in my capabilities to accomplish not only this dissertation but much more in life and their words of love and encouragement have continuously given me the strength and the will to give my research my very best. My father‘s great enthusiasm for this project, his intellectual input and his practical help and advice during the fieldwork of this project have been formative to this project. I would like to thank my dissertation advisor George Steinmetz for the many engaged conversations about theory and methods, for always pushing me to take my work to the next level and above all for teaching me to recognize and avoid sloppiness, caricatures and short-cuts. It is to him that I owe my greatest intellectual debt. -

4.8B Private Sector Universities/Degree Awarding Institutions Federal 1

4.8b Private Sector Universities/Degree Awarding Institutions Federal 1. Foundation University, Islamabad 2. National University of Computer and Emerging Sciences, Islamabad 3. Riphah International University, Islamabad Punjab 1. Hajvery University, Lahore 2. Imperial College of Business Studies, Lahore 3. Institute of Management & Technology, Lahore 4. Institute of Management Sciences, Lahore 5. Lahore School of Economics, Lahore 6. Lahore University of Management Sciences, Lahore 7. National College of Business Administration & Economics, Lahore 8. University of Central Punjab, Lahore 9. University of Faisalabad, Faisalabad 10. University of Lahore, Lahore 11. Institute of South Asia, Lahore Sindh 1. Aga Khan University, Karachi 2. Baqai Medical University, Karachi 3. DHA Suffa University, Karachi 4. Greenwich University, Karachi 5. Hamdard University, Karachi 6. Indus Valley School of Art and Architecture, Karachi 7. Institute of Business Management, Karachi 8. Iqra University, Karachi 9. Isra University, Hyderabad 10. Jinnah University for Women, Karachi 11. Karachi Institute of Economics & Technology, Karachi 12. KASB Institute of Technology, Karachi 13. Muhammad Ali Jinnah University, Karachi 56 14. Newport Institute of Communications & Economics, Karachi 15. Preston Institute of Management, Science and Technology, Karachi 16. Shaheed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto Institute of Science and Technology (SZABIST), Karachi 17. Sir Syed University of Engineering and Technology, Karachi 18. Textile Institute of Pakistan, Karachi 19. Zia-ud-Din Medical University, Karachi 20. Biztek Institute of Business Technology, Karachi 21. Dada Bhoy Institute of Higher Education, Karachi NWFP 1. CECOS University of Information Technology & Emerging Sciences, Peshawar 2. City University of Science and Information Technology, Peshawar 3. Gandhara University, Peshawar 4. Ghulam Ishaq Khan Institute of Engineering Sciences & Technology, Topi 5. -

Imports-Exports Enterprise’: Understanding the Nature of the A.Q

Not a ‘Wal-Mart’, but an ‘Imports-Exports Enterprise’: Understanding the Nature of the A.Q. Khan Network Strategic Insights , Volume VI, Issue 5 (August 2007) by Bruno Tertrais Strategic Insights is a bi-monthly electronic journal produced by the Center for Contemporary Conflict at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California. The views expressed here are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of NPS, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. Introduction Much has been written about the A.Q. Khan network since the Libyan “coming out” of December 2003. However, most analysts have focused on the exports made by Pakistan without attempting to relate them to Pakistani imports. To understand the very nature of the network, it is necessary to go back to its “roots,” that is, the beginnings of the Pakistani nuclear program in the early 1970s, and then to the transformation of the network during the early 1980s. Only then does it appear clearly that the comparison to a “Wal-Mart” (the famous expression used by IAEA Director General Mohammed El-Baradei) is not an appropriate description. The Khan network was in fact a privatized subsidiary of a larger, State-based network originally dedicated to the Pakistani nuclear program. It would be much better characterized as an “imports-exports enterprise.” I. Creating the Network: Pakistani Nuclear Imports Pakistan originally developed its nuclear complex out in the open, through major State-approved contracts. Reprocessing technology was sought even before the launching of the military program: in 1971, an experimental facility was sold by British Nuclear Fuels Ltd (BNFL) in 1971. -

Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto and Confrontationist Power Politics in Pakistan : JRSP, Vol

Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto and Confrontationist Power Politics in Pakistan : JRSP, Vol. 58, No 2 (April-June 2021) Ulfat Zahra Javed Iqbal Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto and the Beginning of Confrontationist Power Politics in Pakistan 1971-1977 Abstract: This paper mainly explores the genesis of power politics in Pakistan during 1971-1977. The era witnessed political disorders that the country had experienced after the tragic event of the separation of East Pakistan. Bhutto’s desire for absolute power and his efforts to introduce a system that would make him the main force in power alienated both, the opposition and his colleagues and supporters. Instead of a democratic stance on competitive policies, he adopted an authoritarian style and confronted the National People's Party, leading to an era characterized by power politics and personality clashes between the stalwarts of the time. This mutual distrust between Bhutto and the opposition - led to a coalition of diverse political groups in the opposition, forming alliances such as the United Democratic Front and the Pakistan National Alliance to counter Bhutto's attempts of establishing a sort of civilian dictatorship. This study attempts to highlight the main theoretical and political implications of power politics between the ruling PPP and the opposition parties which left behind deep imprints on the history of Pakistan leading to the imposition of martial law in 1977. If the political parties tackle the situation with harmony, a firm democracy can establish in Pakistan. Keywords: Pakhtun Students Federation, Dehi Mohafiz, Shahbaz (Newspaper), Federal Security Force. Introduction The loss of East Pakistan had caused great demoralization in the country. -

Alternative Narratives for Preventing the Radicalization of Muslim Youth By

Spring /15 Nr. 2 ISSN: 2363-9849 Alternative Narratives for Preventing the Radicalization of Muslim Youth By: Dr. Afzal Upal 1 Introduction The international jihadist movement has declared war. They have declared war on anybody who does not think and act exactly as they wish they would think and act. We may not like this and wish it would go away, but it’s not going to go away, and the reality is we are going to have to confront it. (Prime Minister Steven Harper, 8 Jan 2015) With an increasing number of Western Muslims falling prey to violent extremist ideologies and joining Jihadi organizations such as Al-Qaida and the ISIS, Western policy makers have been concerned with preventing radicalization of Muslim youth. This has resulted in a number of government sponsored efforts (e.g., MyJihad, Sabahi, and Maghrebia (Briggs and Feve 2013)) to counter extremist propaganda by arguing that extremist violent tactics used by Jihadist organizations are not congruent with Islamic tenets of kindness and just war. Despite the expenditure of significant resources since 2001, these efforts have had limited success. This article argues that in order to succeed we need to better understand Muslim core social identity beliefs (i.e., their perception of what it means to be a good Muslim) and how these beliefs are connected to Muslims perceptions of Westerners. A better understanding of the interdependent nature and dynamics of these beliefs will allow us to design counter radicalization strategies that have a better chance of success. 1 Dr. M Afzal Upal is a cognitive scientist of religion with expertise in the Islamic social and religious movements. -

Political Development, the People's Party of Pakistan and the Elections of 1970

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1973 Political development, the People's Party of Pakistan and the elections of 1970. Meenakshi Gopinath University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Gopinath, Meenakshi, "Political development, the People's Party of Pakistan and the elections of 1970." (1973). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2461. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/2461 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FIVE COLLEGE DEPOSITORY POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT, THE PEOPLE'S PARTY OF PAKISTAN AND THE ELECTIONS OF 1970 A Thesis Presented By Meenakshi Gopinath Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS June 1973 Political Science POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT, THE PEOPLE'S PARTY OF PAKISTAN AND THE ELECTIONS OF 1970 A Thesis Presented By Meenakshi Gopinath Approved as to style and content hy: Prof. Anwar Syed (Chairman of Committee) f. Glen Gordon (Head of Department) Prof. Fred A. Kramer (Member) June 1973 ACKNOWLEDGMENT My deepest gratitude is extended to my adviser, Professor Anwar Syed, who initiated in me an interest in Pakistani poli- tics. Working with such a dedicated educator and academician was, for me, a totally enriching experience. I wish to ex- press my sincere appreciation for his invaluable suggestions, understanding and encouragement and for synthesizing so beautifully the roles of Friend, Philosopher and Guide. -

Son of the Desert

Dedicated to Mohtarma Benazir Bhutto Shaheed without words to express anything. The Author SONiDESERT A biography of Quaid·a·Awam SHAHEED ZULFIKAR ALI H By DR. HABIBULLAH SIDDIQUI Copyright (C) 2010 by nAfllST Printed and bound in Pakistan by publication unit of nAfllST Shaheed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto/Shaheed Benazir Bhutto Archives. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. First Edition: April 2010 Title Design: Khuda Bux Abro Price Rs. 650/· Published by: Shaheed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto/ Shaheed Benazir Bhutto Archives 4.i. Aoor, Sheikh Sultan Trust, Building No.2, Beaumont Road, Karachi. Phone: 021-35218095-96 Fax: 021-99206251 Printed at: The Time Press {Pvt.) Ltd. Karachi-Pakistan. CQNTENTS Foreword 1 Chapter: 01. On the Sands of Time 4 02. The Root.s 13 03. The Political Heritage-I: General Perspective 27 04. The Political Heritage-II: Sindh-Bhutto legacy 34 05. A revolutionary in the making 47 06. The Life of Politics: Insight and Vision· 65 07. Fall out with the Field Marshal and founding of Pakistan People's Party 108 08. The state dismembered: Who is to blame 118 09. The Revolutionary in the saddle: New Pakistan and the People's Government 148 10. Flash point.s and the fallout 180 11. Coup d'etat: tribulation and steadfasmess 197 12. Inside Death Cell and out to gallows 220 13. Home they brought the warrior dead 229 14. -

Federal Urdu University of Arts, Sciences & Technology

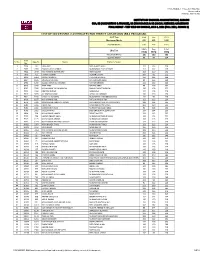

Degree Year Of Student Selection Campus Department Title Study Full Name Father Name CNIC Degree Title CGPA Status Merit Status Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 Khizra Khalil Khalil Ahmed Bajwa 6110152362736 BS (Hons) 3.2 Selected Student Eligible Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 ANAM ZHARA SYED AKHTER HUSSAIN SHAH 3740319867784 BS (Hons) 3.3 Selected Student Eligible Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 masood ur rehman Rehan shah 2140792271819 BS (Hons) 3.16 Selected Student Eligible Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 Muhammad Irfan Allah Dewaya 3220336130281 BS (Hons) 3.6 Selected Student Eligible Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 Ahsan Iftikhar Iftikhar Ahmad 3720114487337 BS (Hons) 3.58 Selected Student Eligible Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 Qurat Ul Ain Aziz Ullah Khan 3830101789040 BS (Hons) 3.18 Selected Student Eligible Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 Muhammad Majid Muhammad Faridoon 3740589951603 BS (Hons) 3.51 Selected Student Eligible Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 Abdul Manan Muhammad Saleem 3740341694235 BS (Hons) 3.88 Selected Student Eligible Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 Muhammad Awais Muhammad Saeed 3710293250617 BS (Hons) 3.55 Selected Student Eligible Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 MAYA SYED SYED TAFAZUL HASSAN 6110194455878 BS (Hons) 3.7 Selected Student Eligible Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 Mehreen Bibi Faqar Din 8220209594876 BS (Hons) 3.2 Selected Student Eligible Islamabad Applied Physics Bachelors 1 AMBREEN SAFDAR MALIK SAFDAR HUSSAIN 6110192701214 -

Pakistan Courting the Abyss by Tilak Devasher

PAKISTAN Courting the Abyss TILAK DEVASHER To the memory of my mother Late Smt Kantaa Devasher, my father Late Air Vice Marshal C.G. Devasher PVSM, AVSM, and my brother Late Shri Vijay (‘Duke’) Devasher, IAS ‘Press on… Regardless’ Contents Preface Introduction I The Foundations 1 The Pakistan Movement 2 The Legacy II The Building Blocks 3 A Question of Identity and Ideology 4 The Provincial Dilemma III The Framework 5 The Army Has a Nation 6 Civil–Military Relations IV The Superstructure 7 Islamization and Growth of Sectarianism 8 Madrasas 9 Terrorism V The WEEP Analysis 10 Water: Running Dry 11 Education: An Emergency 12 Economy: Structural Weaknesses 13 Population: Reaping the Dividend VI Windows to the World 14 India: The Quest for Parity 15 Afghanistan: The Quest for Domination 16 China: The Quest for Succour 17 The United States: The Quest for Dependence VII Looking Inwards 18 Looking Inwards Conclusion Notes Index About the Book About the Author Copyright Preface Y fascination with Pakistan is not because I belong to a Partition family (though my wife’s family Mdoes); it is not even because of being a Punjabi. My interest in Pakistan was first aroused when, as a child, I used to hear stories from my late father, an air force officer, about two Pakistan air force officers. In undivided India they had been his flight commanders in the Royal Indian Air Force. They and my father had fought in World War II together, flying Hurricanes and Spitfires over Burma and also after the war. Both these officers later went on to head the Pakistan Air Force. -

Announced on Monday, July 19, 2021

FINAL RESULT - FALL 2021 ROUND 2 Announced on Monday, July 19, 2021 INSTITUTE OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, KARACHI BBA, BS (ACCOUNTING & FINANCE), BS (ECONOMICS) & BS (SOCIAL SCIENCES) ADMISSIONS FINAL RESULT ‐ TEST HELD ON SUNDAY, JULY 4, 2021 (FALL 2021, ROUND 2) LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES FOR DIRECT ADMISSION (BBA PROGRAM) SAT Test Math Eng TOTAL Maximum Marks 800 800 1600 Cut-Off Marks 600 600 1420 Math Eng Total IBA Test MCQ MCQ MCQ Maximum Marks 180 180 360 Cut-Off Marks 88 88 224 Seat S. No. App No. Name Father's Name No. 1 7904 30 LAIBA RAZI RAZI AHMED JALALI 112 116 228 2 7957 2959 HASSAAN RAZA CHINOY MUHAMMAD RAZA CHINOY 112 132 244 3 7962 3549 MUHAMMAD SHAYAN ARIF ARIF HUSSAIN 152 120 272 4 7979 455 FATIMA RIZWAN RIZWAN SATTAR 160 92 252 5 8000 1464 MOOSA SHERGILL FARZAND SHERGILL 124 124 248 6 8937 1195 ANAUSHEY BATOOL ATTA HUSSAIN SHAH 92 156 248 7 8938 1200 BIZZAL FARHAN ALI MEMON FARHAN MEMON 112 112 224 8 8978 2248 AFRA ABRO NAVEED ABRO 96 136 232 9 8982 2306 MUHAMMAD TALHA MEMON SHAHID PARVEZ MEMON 136 136 272 10 9003 3266 NIRDOSH KUMAR NARAIN NA 120 108 228 11 9017 3635 ALI SHAZ KARMANI IMTIAZ ALI KARMANI 136 100 236 12 9031 1945 SAIFULLAH SOOMRO MUHAMMAD IBRAHIM SOOMRO 132 96 228 13 9469 1187 MUHAMMAD ADIL RAFIQ AHMAD KHAN 112 112 224 14 9579 2321 MOHAMMAD ABDULLAH KUNDI MOHAMMAD ASGHAR KHAN KUNDI 100 124 224 15 9582 2346 ADINA ASIF MALIK MOHAMMAD ASIF 104 120 224 16 9586 2566 SAMAMA BIN ASAD MUHAMMAD ASAD IQBAL 96 128 224 17 9598 2685 SYED ZAFAR ALI SYED SHAUKAT HUSSAIN SHAH 124 104 228 18 9684 526 MUHAMMAD HAMZA -

Politics of Sindh Under Zia Government an Analysis of Nationalists Vs Federalists Orientations

POLITICS OF SINDH UNDER ZIA GOVERNMENT AN ANALYSIS OF NATIONALISTS VS FEDERALISTS ORIENTATIONS A Thesis Doctor of Philosophy By Amir Ali Chandio 2009 Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University Multan POLITICS OF SINDH UNDER ZIA GOVERNMENT AN ANALYSIS OF NATIONALISTS VS FEDERALISTS ORIENTATIONS A Thesis Doctor of Philosophy By Amir Ali Chandio 2009 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Ishtiaq Ahmed Chaudhry Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University Multan Dedicated to: Baba Bullay Shah & Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai The poets of love, fraternity, and peace DECLARATION This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………………….( candidate) Date……………………………………………………………………. CERTIFICATES This is to certify that I have gone through the thesis submitted by Mr. Amir Ali Chandio thoroughly and found the whole work original and acceptable for the award of the degree of Doctorate in Political Science. To the best of my knowledge this work has not been submitted anywhere before for any degree. Supervisor Professor Dr. Ishtiaq Ahmed Choudhry Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan, Pakistan Chairman Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan, Pakistan. ABSTRACT The nationalist feelings in Sindh existed long before the independence, during British rule. The Hur movement and movement of the separation of Sindh from Bombay Presidency for the restoration of separate provincial status were the evidence’s of Sindhi nationalist thinking.