Repositório ISCTE-IUL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Innoheis: Research & Innovation Infrastructure

Subscribe Past Issues Tra View this email in your browser InnoHEIs project keeps on going! We live in strange times, especially for international projects like InnoHEIs. The partner meetings planned in Barcelona and Mid Sweden couldn't go through due to COVID-19 measures. It was a pity the team could not meet in person. Instead all partners met online twice to share and learn about research and innovation infrastructure! The first online session with all the partners was end of March, when we were supposed to see each other in the region of Catalonia. Partners discussed the Subscriberegional diagnosisPast Issues they are preparing for the project: what are the research and Tra innovations structures like in the different regions? The interview with the Risk and Crisis Research Centre in Mid Sweden is part of this. More results will follow soon. Swedish students pitch for InnoHEIs In May there was a meeting for all partners planned in Sweden. Instead of this, we had a second virtual partner meeting with inspiring pitches from winning students of the Mid Sweden University! They had to come up with an answer to the following question in just one day. How would you design the future for North Middle Sweden, 2030? They had to fulfil one of the united nations 17 sustainable goals and include cooperation with two of the other European partners in the InnoHEIs project. Subscribe Past Issues Tra Risk and Crisis Research Centre adds to Swedish innovation For the regional diagnosis Mid Sweden University interviews the leaders of the research and innovation infrastructure in the region of Middle Norrland. -

Regional Disparity and Heterogeneous Income Effects of the Euro

Better out than in? Regional disparity and heterogeneous income effects of the euro Sang-Wook (Stanley) Cho1,∗ School of Economics, UNSW Business School, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia Sally Wong2 Economic Analysis Department, Reserve Bank of Australia, Sydney, Australia February 14, 2021 Abstract This paper conducts a counterfactual analysis on the effect of adopting the euro on regional income and disparity within Denmark and Sweden. Using the synthetic control method, we find that Danish regions would have experienced small heterogeneous effects from adopting the euro in terms of GDP per capita, while all Swedish regions are better off without the euro with varying magnitudes. Adopting the euro would have decreased regional income disparity in Denmark, while the effect is ambiguous in Sweden due to greater convergence among non-capital regions but further divergence with Stockholm. The lower disparity observed across Danish regions and non-capital Swedish regions as a result of eurozone membership is primarily driven by losses suffered by high-income regions rather than from gains to low- income regions. These results highlight the cost of foregoing stabilisation tools such as an independent monetary policy and a floating exchange rate regime. For Sweden in particular, macroeconomic stability outweighs the potential efficiency gains from a common currency. JEL classification: Keywords: currency union, euro, synthetic control method, regional income disparity ∗Corresponding author. We would like to thank Glenn Otto, Pratiti Chatterjee, Scott French, Federico Masera and Alan Woodland for their constructive feedback and comments. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the Reserve Bank of Australia. -

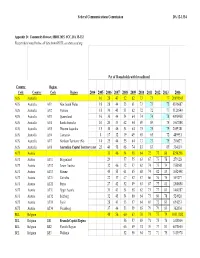

DA-15-132A6.Pdf

Federal Communications Commission DA 12-1334 Appendix D: Community Dataset, IBDR 2015, FCC, DA 15-132 Except where noted below, all data from OECD, see stats.oecd.org Pct of Households with broadband Country Region Code Country Code Region 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2006 AUS Australia 16 28 43 52 62 73 73 77 20695501 AUS Australia AU1 New South Wales 18 28 44 53 61 73 73 75 6816087 AUS Australia AU2 Victoria 18 30 45 51 62 72 72 77 5126540 AUS Australia AU3 Queensland 16 30 44 54 64 74 74 78 4090908 AUS Australia AU4 South Australia 10 20 33 42 54 69 69 75 1567888 AUS Australia AU5 Western Australia 15 30 46 54 64 75 75 79 2059381 AUS Australia AU6 Tasmania 8 17 32 39 49 65 65 72 489951 AUS Australia AU7 Northern Territorry (Nt) 14 25 44 55 64 73 73 79 210627 AUS Australia AU8 Australian Capital Territory (Act) 23 40 58 68 74 83 83 85 334119 AUT Austria 33 46 54 58 64 72 77 80 8254298 AUT Austria AT11 Burgenland 29 57 55 63 67 73 78 279128 AUT Austria AT12 Lower Austria 32 46 52 57 62 74 75 74 1580501 AUT Austria AT13 Vienna 45 55 61 65 68 74 82 83 1652448 AUT Austria AT21 Carinthia 22 37 47 52 57 66 76 75 559277 AUT Austria AT22 Styria 27 42 52 49 63 67 77 81 1200854 AUT Austria AT31 Upper Austria 31 43 54 58 62 73 77 81 1400287 AUT Austria AT32 Salzburg 32 45 54 60 64 73 80 78 524920 AUT Austria AT33 Tyrol 28 43 53 57 64 69 72 83 694253 AUT Austria AT34 Vorarlberg 37 44 53 59 65 79 79 83 362630 BEL Belgium 48 56 60 63 70 74 75 79 10511382 BEL Belgium BE1 Brussels Capital Region 56 57 65 71 75 76 1018804 BEL Belgium -

The Genetic Structure of the Swedish Population

The Genetic Structure of the Swedish Population Keith Humphreys1, Alexander Grankvist1, Monica Leu1, Per Hall1, Jianjun Liu2, Samuli Ripatti3,4, Karola Rehnstro¨ m5, Leif Groop6, Lars Klareskog7, Bo Ding7, Henrik Gro¨ nberg1, Jianfeng Xu8,9, Nancy L. Pedersen1, Paul Lichtenstein1, Morten Mattingsdal10,11, Ole A. Andreassen10,12, Colm O’Dushlaine13,14, Shaun M. Purcell13,14, Pamela Sklar13,14, Patrick F. Sullivan15, Christina M. Hultman1, Juni Palmgren1,16,17, Patrik K. E. Magnusson1* 1 Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, 2 Human Genetics Laboratory, Genome Institute of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore, 3 Institute for Molecular Medicine, Finland, FIMM, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland, 4 Public Health Genomics Unit, National Institute for Health and Welfare, Helsinki, Finland, 5 Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Wellcome Trust Genome Campus, Hinxton, United Kingdom, 6 Department of Clinical Sciences, Diabetes and Endocrinology, Lund University Diabetes Centre, Malmo¨, Sweden, 7 Institute of Environmental Medicine, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, 8 Department of Cancer Biology and Comprehensive Cancer Center, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, United States of America, 9 Center for Cancer Genomics, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, United States of America, 10 Institute of Clinical Medicine, Section Psychiatry, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway, 11 Sørlandet Hospital HF, Kristiansand, -

The Economical Geography of Swedish Norrland Author(S): Hans W:Son Ahlmann Source: Geografiska Annaler, Vol

The Economical Geography of Swedish Norrland Author(s): Hans W:son Ahlmann Source: Geografiska Annaler, Vol. 3 (1921), pp. 97-164 Published by: Wiley on behalf of Swedish Society for Anthropology and Geography Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/519426 Accessed: 27-06-2016 10:05 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Swedish Society for Anthropology and Geography, Wiley are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Geografiska Annaler This content downloaded from 137.99.31.134 on Mon, 27 Jun 2016 10:05:39 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms THE ECONOMICAL GEOGRAPHY OF SWEDISH NORRLAND. BY HANS W:SON AHLMrANN. INTRODUCTION. T he position of Sweden can scarcely be called advantageous from the point of view of commercial geography. On its peninsula in the north-west cor- ner of Europe, and with its northern boundary abutting on the Polar world, it forms a backwater to the main stream of Continental communications. The southern boundary of Sweden lies in the same latitude as the boundary between Scotland and England, and as Labrador and British Columbia in America; while its northern boundary lies in the same latitude as the northern half of Greenland and the Arctic archipelago of America. -

Regions and Cities at a Glance 2020

Regions and Cities at a Glance 2020 provides a comprehensive assessment of how regions and cities across the OECD are progressing in a number of aspects connected to economic development, health, well-being and net zero-carbon transition. In the light of the health crisis caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, the report analyses outcomes and drivers of social, economic and environmental resilience. Consult the full publication here. OECD REGIONS AND CITIES AT A GLANCE - COUNTRY NOTE SWEDEN A. Resilient regional societies B. Regional economic disparities and trends in productivity C. Well-being in regions D. Industrial transition in regions E. Transitioning to clean energy in regions F. Metropolitan trends in growth and sustainability The data in this note reflect different subnational geographic levels in OECD countries: • Regions are classified on two territorial levels reflecting the administrative organisation of countries: large regions (TL2) and small regions (TL3). Small regions are classified according to their access to metropolitan areas (see https://doi.org/10.1787/b902cc00-en). • Functional urban areas consists of cities – defined as densely populated local units with at least 50 000 inhabitants – and adjacent local units connected to the city (commuting zones) in terms of commuting flows (see https://doi.org/10.1787/d58cb34d-en). Metropolitan areas refer to functional urban areas above 250 000 inhabitants. Regions and Cities at a Glance 2020 Austria country note 2 A. Resilient regional societies Stockholm has the highest potential for remote working A1. Share of jobs amenable to remote working, 2018 Large regions (TL2, map) LUX GBR AUS SWE CHE NLD ISL DNK FRA High (>40%) FIN NOR BEL 3540-50%-40% LTU EST 3030-40%-35% IRL GRC 2520-30%-30% DEU AUT Low (<25%) LVA SVN OECD30 PRT HRV POL ITA USA CZE HUN CAN ESP ROU SVK BGR TUR COL 0 10 20 30 40 50 % The share of jobs amenable to remote working across Swedish regions range from close to 50% in Stockholm to 33% in North Middle Sweden (Figure A1). -

Cross-Border Scandinavian Area Case Study

CIRCTER SPIN-OFF // Cross-border Scandinavian area Case study Final Report // May 2021 This CIRCTER spin-off is conducted within the framework of the ESPON 2020 Cooperation Programme, partly financed by the European Regional Development Fund. The ESPON EGTC is the Single Beneficiary of the ESPON 2020 Cooperation Programme. The Single Operation within the programme is implemented by the ESPON EGTC and co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund, the EU Member States and the Partner States, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. This delivery does not necessarily reflect the opinions of members of the ESPON 2020 Monitoring Committee. Authors Marco Bianchi, Mauro Cordella, Pierre Merger - Tecnalia Research and Innovation, Spain Advisory group Jan Edøy - Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, Department of Regional Development, Norway Erik Hagen, Bjørn Terje Andersen – Innlandet County Authority, Norway Marjan van Herwijnen - ESPON EGTC Information on ESPON and its projects can be found at www.espon.eu. The website provides the possibility to download and examine the most recent documents produced by finalised and ongoing ESPON projects. ISBN: 978-2-919795-97-0 © ESPON, 2020 Layout and graphic design by BGRAPHIC, Denmark Printing, reproduction or quotation is authorised provided the source is acknowledged and a copy is forwarded to the ESPON EGTC in Luxembourg. Contact: [email protected] CIRCTER SPIN-OFF // Cross-border Scandinavian area Case study Final Report // May 2021 CIRCTER SPIN-OFF // Cross-border Scandinavian -

Country Report on Achievements of Cohesion Policy, Sweden

ISMERI EUROPA EXPERT EVALUATION NENETWORKTWORK DELIVERING POLICY ANANALYSISALYSIS ON THE PERFORMANCE OF COHESCOHESIONION POLICY 20072007----20132013 YEAR 1 ––– 2011 TASK 2: COUNTRY REPOREPORTRT ON ACHIEVEMENTS OOFF COHESION POLICY SWEDEN VVVERSION ::: FFFINAL JJJANANAN ---E-EEEVERT NNNILSSON JENA A report to the European Commission DirectorateDirectorate----GeneralGeneral Regional Policy EEN2011 Task 2: Country Report on Achievements of Cohesion Policy CONTENTS Executive summary ............................................................................................................... 3 1. The socio-economic context .......................................................................................... 5 2. The regional development policy pursued, the EU contribution to this and policy achievements over the period................................................................................................ 7 The regional development policy pursued .......................................................................... 7 Policy implementation ........................................................................................................ 9 Achievements of the programmes so far .......................................................................... 12 3. Effects of intervention .................................................................................................. 17 4. Evaluations and good practice in evaluation ................................................................. 20 5. Concluding remarks -

A Seismological Map of Northern Europe

SVERIGES GEOLOGISKA UNDERSÖKNING SER. c. Avhandlingar och uppsatser. ÅRSBOK (1930) N:o r. A SEISMOLOGICAL MAP OF NORTHERN EUROPE BY K. E. S A H L S T R Ö M WITH ONE PLATE Prz"s 0.50 kr. STOCKHOLM 1930 KUNGL. BOKTRYCKERIET. P. A. NORSTEDT & SÖNER 302302 SVERIGES GEOLOGISKA UNDERSÖKNING SER. c. A v handlingar och uppsats er. ÅRSBOK (1930) N:o r. A SEISMOLOGICAL MAP OF NORTHERN EUROPE BY K . E . S A H L STRÖM W ITH ONE PLATE STOCKHOLM 1930 KUNGL. BOKTRVCKER!ET . P. A . NORSTEDT & SÖNER 302302 In his valuable memoir )>Sveriges jordskalv)> (Earthquakes in Sweden) (5), Rudolf Kjellen in rgro gave a survey of. the seismic conditions in Sweden. He publishes a list of all earthquakes that have been observed and recorded in the country, compiled from a great number of different sources. The cata logue, which goes from the year 1375 to rgo6, contains 421 earthquakes. On the basis of this material, Kjellen has constructed a seismic map of Sweden, using the following method. According to its size, each earthquake is given 1 a certain figure valne (in )>earthquake units)>) from / 2 to 5, while information that earthquakes are of frequent occurrence is ratedas ro. Taking into consi deration the distribution of the more important shocks, the country is then divided into a number of zones, and the degree of seismicity within these zones is expressed in the number of square kilometers for each )>earthquake unib within the time considered. The map shows strongly seismic regions around Lake Vänern, along the Bothnian Gulf, in Halland, and in sontheastern Skåne. -

OECD Territorial Grids

BETTER POLICIES FOR BETTER LIVES DES POLITIQUES MEILLEURES POUR UNE VIE MEILLEURE OECD Territorial grids August 2021 OECD Centre for Entrepreneurship, SMEs, Regions and Cities Contact: [email protected] 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Territorial level classification ...................................................................................................................... 3 Map sources ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Map symbols ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Disclaimers .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Australia / Australie ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Austria / Autriche ......................................................................................................................................... 7 Belgium / Belgique ...................................................................................................................................... 9 Canada ...................................................................................................................................................... -

Financial Instruments and Territorial Cohesion

Financial Instruments and Territorial Cohesion Mellersta Norrland/Sweden Case Study Report 30/08/2019 This applied research activity is conducted within the framework of the ESPON 2020 Cooperation Programme, partly financed by the European Regional Development Fund. The ESPON EGTC is the Single Beneficiary of the ESPON 2020 Cooperation Programme. The Single Operation within the programme is implemented by the ESPON EGTC and co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund, the EU Member States and Partner States, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. This delivery does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the members of the ESPON 2020 Monitoring Committee. Authors Viktor Salenius, Nordregio (Sweden) John Moodie, Nordregio (Sweden) Kaisa Granqvist, Aalto University (Finland) Advisory Group Project Support Team: Cristina Wallez Cuevas, General Commission for Territorial Equality, France; Adriana May, Lombardia Region, Italy; Joerg Lackenbauer, European Commission ESPON EGTC: Zintis Hermansons (Project expert) and Akos Szabo (Financial expert). Acknowledgements We would like to thank Jörgen Larsson, CEO of Inlandsinnovation (formerly Mittkapital); Eva Nordlander, CEO of Almi Invest in Mellersta Norrland; Lars Karbin, Chairman of the Board of Startkapital I Norr AB; Mattias Lööv, CEO of H1 Communication AB; Tobias Sjölander, CEO of Loxysoft AB, for taking the time to offer their useful thoughts, ideas and insights on the Swedish financial instruments ecosystem. Information on ESPON and its projects can be found on www.espon.eu. The website provides the possibility to download and examine the most recent documents produced by finalised and ongoing ESPON projects. This delivery exists only in an electronic version. © ESPON, 2019 Printing, reproduction or quotation is authorised provided the source is acknowledged and a copy is forwarded to the ESPON EGTC in Luxembourg. -

Pilot Project on Industrial Transition

RAPPORT Datum 2018-06-11 Enheten för regional tillväxt Maja Sörensen [email protected] Pilot project on industrial transition Material on Norra Mellansverige used for the peer learning workshops organized by the European Commission and OECD spring 2018 Region Värmland - kommunalförbund Postadress Besöksadress Telefon 054-701 10 00 vx Orgnr 222000-1362 Box 1022 Lagergrens gata 2 Fax 054-701 10 01 Bankgiro 5344-2984 651 15 KARLSTAD E-post [email protected] PlusGiro 437 33 98-9 Webbplats www.regionvarmland.se REGION VÄRMLAND 2018-06-11 2 Contents 1 Introduction ................................................................................................ 3 2 Workshop 2: Broadening innovation and innovation diffusion ............ 5 3 Workshop 3: Low carbon energy transition ........................................... 9 4 Workshop 4: Promoting entrepreneurship and mobilising the private sector ............................................................................................................ 16 5 Workshop 5: Inclusive growth ................................................................ 22 REGION VÄRMLAND 2018-06-11 3 1 Introduction In July 2017 the European Commission presented new ways to help regions build resilient economies in new times by going further with the regional smart specialisation strategies. One of the actions initiated was two new pilot projects and Norra Mellansverige was selected to participate in the pilot “Tailored support for the specific challenges on regions facing industrial transition”