The Political Representation of the Poor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Document Country: Macedonia Lfes ID: Rol727

Date Printed: 11/06/2008 JTS Box Number: lFES 7 Tab Number: 5 Document Title: Macedonia Final Report, May 2000-March 2002 Document Date: 2002 Document Country: Macedonia lFES ID: ROl727 I I I I I I I I I IFES MISSION STATEMENT I I The purpose of IFES is to provide technical assistance in the promotion of democracy worldwide and to serve as a clearinghouse for information about I democratic development and elections. IFES is dedicated to the success of democracy throughout the world, believing that it is the preferred form of gov I ernment. At the same time, IFES firmly believes that each nation requesting assistance must take into consideration its unique social, cultural, and envi I ronmental influences. The Foundation recognizes that democracy is a dynam ic process with no single blueprint. IFES is nonpartisan, multinational, and inter I disciplinary in its approach. I I I I MAKING DEMOCRACY WORK Macedonia FINAL REPORT May 2000- March 2002 USAID COOPERATIVE AGREEMENT No. EE-A-00-97-00034-00 Submitted to the UNITED STATES AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT by the INTERNATIONAL FOUNDATION FOR ELECTION SYSTEMS I I TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTNE SUMMARY I I. PROGRAMMATIC ACTNITIES ............................................................................................. 1 A. 2000 Pre Election Technical Assessment 1 I. Background ................................................................................. 1 I 2. Objectives ................................................................................... 1 3. Scope of Mission .........................................................................2 -

Who Gains from Apparentments Under D'hondt?

CIS Working Paper No 48, 2009 Published by the Center for Comparative and International Studies (ETH Zurich and University of Zurich) Who gains from apparentments under D’Hondt? Dr. Daniel Bochsler University of Zurich Universität Zürich Who gains from apparentments under D’Hondt? Daniel Bochsler post-doctoral research fellow Center for Comparative and International Studies Universität Zürich Seilergraben 53 CH-8001 Zürich Switzerland Centre for the Study of Imperfections in Democracies Central European University Nador utca 9 H-1051 Budapest Hungary [email protected] phone: +41 44 634 50 28 http://www.bochsler.eu Acknowledgements I am in dept to Sebastian Maier, Friedrich Pukelsheim, Peter Leutgäb, Hanspeter Kriesi, and Alex Fischer, who provided very insightful comments on earlier versions of this paper. Manuscript Who gains from apparentments under D’Hondt? Apparentments – or coalitions of several electoral lists – are a widely neglected aspect of the study of proportional electoral systems. This paper proposes a formal model that explains the benefits political parties derive from apparentments, based on their alliance strategies and relative size. In doing so, it reveals that apparentments are most beneficial for highly fractionalised political blocs. However, it also emerges that large parties stand to gain much more from apparentments than small parties do. Because of this, small parties are likely to join in apparentments with other small parties, excluding large parties where possible. These arguments are tested empirically, using a new dataset from the Swiss national parliamentary elections covering a period from 1995 to 2007. Keywords: Electoral systems; apparentments; mechanical effect; PR; D’Hondt. Apparentments, a neglected feature of electoral systems Seat allocation rules in proportional representation (PR) systems have been subject to widespread political debate, and one particularly under-analysed subject in this area is list apparentments. -

A Canadian Model of Proportional Representation by Robert S. Ring A

Proportional-first-past-the-post: A Canadian model of Proportional Representation by Robert S. Ring A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Political Science Memorial University St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador May 2014 ii Abstract For more than a decade a majority of Canadians have consistently supported the idea of proportional representation when asked, yet all attempts at electoral reform thus far have failed. Even though a majority of Canadians support proportional representation, a majority also report they are satisfied with the current electoral system (even indicating support for both in the same survey). The author seeks to reconcile these potentially conflicting desires by designing a uniquely Canadian electoral system that keeps the positive and familiar features of first-past-the- post while creating a proportional election result. The author touches on the theory of representative democracy and its relationship with proportional representation before delving into the mechanics of electoral systems. He surveys some of the major electoral system proposals and options for Canada before finally presenting his made-in-Canada solution that he believes stands a better chance at gaining approval from Canadians than past proposals. iii Acknowledgements First of foremost, I would like to express my sincerest gratitude to my brilliant supervisor, Dr. Amanda Bittner, whose continuous guidance, support, and advice over the past few years has been invaluable. I am especially grateful to you for encouraging me to pursue my Master’s and write about my electoral system idea. -

Eui Working Papers

Repository. Research Institute University UR P 20 European Institute. Cadmus, % European University Institute, Florence on University Access European EUI Working Paper SPS No. 94/16 Open Another Revolution The PDS inItaly’s Transition SOCIALSCIENCES WORKING IN POLITICALIN AND PAPERS EUI Author(s). Available M artin 1989-1994 The 2020. © in J. B ull Manqué Library EUI ? ? the by produced version Digitised Repository. Research Institute University European Institute. Cadmus, on University Access European Open Author(s). Available The 2020. © in Library EUI the by produced version Digitised Repository. Research Institute University European Institute. EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE, FLORENCE Cadmus, DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL AND AND DEPARTMENTSOCIAL OF POLITICAL SCIENCES on BADIA FIESOLANA, SAN DOMENICO (FI) University Access EUI EUI Working Paper SPS No. 94/16 The PDS in Italy’s Transition Departmentof Politics A Contemporary History Another Revolution European Open Department ofPolitical and Social Sciences European University Institute (1992-93) rodEuropean Studies Research Institute M Universityof Salford Author(s). Available artin 1989-1994 The and 2020. © J. J. in bull M anquil Library EUI the by produced version Digitised Repository. Research Institute University European Institute. Cadmus, on University Access No part of this paper may be reproduced in any form European Open Printed in Italy in December 1994 without permission of the author. I I - 50016 San Domenico (FI) European University Institute Author(s). Available The All rights reserved. 2020. © © Martin J. Bull Badia Fiesolana in Italy Library EUI the by produced version Digitised Repository. Research Institute University European paper will appear in a book edited by Stephen Gundle and Simon Parker, published by Routledge, and which will focus on the changes which Italianpolitics underwent in the period during the author’s period as a Visiting Fellow in the Department of Political and Social Sciences at the European University Institute, Florence. -

Election Calendars: Key Dates to Remember. 2020 Congressional Primary Calendar

Election Calendars: Key Dates to Remember. 2020 Congressional Primary Calendar January February March April May June July August September October November December Primaries Election Day Congressional Primaries Major-party Major-party State Date State Date filing deadline filing deadline Alabama Mar. 3 Nov. 8, 2019 South Carolina Jun. 9 Mar. 30 Arkansas Mar. 3 Nov. 11, 2019 Virginia Jun. 9 Mar. 26 California Mar. 3 Dec. 6, 2019 New York Jun. 23 Apr. 2 North Carolina Mar. 3 Dec. 20, 2019 Utah Jun. 23 Mar. 19 Texas Mar. 3 Dec. 9, 2019 Colorado Jun. 30 Mar. 17 Mississippi Mar. 10 Jan. 15 Oklahoma Jun. 30 Apr. 10 Ohio Mar. 17 Dec. 18, 2019 Arizona Aug. 4 Apr. 6 Illinois Mar. 17 Dec. 2, 2019 Kansas Aug. 4 Jun. 1 Maryland Apr. 28 Feb. 5 Michigan Aug. 4 Apr. 21 Pennsylvania Apr. 28 Feb. 18 Missouri Aug. 4 Mar. 31 Indiana May 5 Feb. 7 Washington Aug. 4 May 15 Nebraska May 12 Feb. 18 (incumbents); Tennessee Aug. 6 Apr. 2 Mar. 2 (non-incumbents) Hawaii Aug. 8 Jun. 2 West Virginia May 12 Jan. 25 Connecticut Aug. 11 Jun. 9 Georgia May 19 Mar. 6 Minnesota Aug. 11 Jun. 2 Idaho May 19 Mar. 13 Vermont Aug. 11 May 28 Kentucky May 19 Jan. 28 Wisconsin Aug. 11 Jun. 1 Oregon May 19 Mar. 10 Alaska Aug. 18 Jun. 1 Iowa Jun. 2 Mar. 13 Florida Aug. 18 Apr. 24 Montana Jun. 2 Mar. 9 Wyoming Aug. 18 May 29 New Jersey Jun. 2 Mar. 30 New Sept. 8 Jun. -

Regional Disparity and Heterogeneous Income Effects of the Euro

Better out than in? Regional disparity and heterogeneous income effects of the euro Sang-Wook (Stanley) Cho1,∗ School of Economics, UNSW Business School, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia Sally Wong2 Economic Analysis Department, Reserve Bank of Australia, Sydney, Australia February 14, 2021 Abstract This paper conducts a counterfactual analysis on the effect of adopting the euro on regional income and disparity within Denmark and Sweden. Using the synthetic control method, we find that Danish regions would have experienced small heterogeneous effects from adopting the euro in terms of GDP per capita, while all Swedish regions are better off without the euro with varying magnitudes. Adopting the euro would have decreased regional income disparity in Denmark, while the effect is ambiguous in Sweden due to greater convergence among non-capital regions but further divergence with Stockholm. The lower disparity observed across Danish regions and non-capital Swedish regions as a result of eurozone membership is primarily driven by losses suffered by high-income regions rather than from gains to low- income regions. These results highlight the cost of foregoing stabilisation tools such as an independent monetary policy and a floating exchange rate regime. For Sweden in particular, macroeconomic stability outweighs the potential efficiency gains from a common currency. JEL classification: Keywords: currency union, euro, synthetic control method, regional income disparity ∗Corresponding author. We would like to thank Glenn Otto, Pratiti Chatterjee, Scott French, Federico Masera and Alan Woodland for their constructive feedback and comments. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the Reserve Bank of Australia. -

A Meta Analysis of County, Gender, and Year Specific Effects of Active Labour Market Programmes

A Meta Analysis of County, Gender, and Year Speci…c E¤ects of Active Labour Market Programmes Agne Lauzadyte Department of Economics, University of Aarhus E-Mail: [email protected] and Michael Rosholm Department of Economics, Aarhus School of Business E-Mail: [email protected] 1 1. Introduction Unemployment was high in Denmark during the 1980s and 90s, reaching a record level of 12.3% in 1994. Consequently, there was a perceived need for new actions and policies in the combat of unemployment, and a law Active Labour Market Policies (ALMPs) was enacted in 1994. The instated policy marked a dramatic regime change in the intensity of active labour market policies. After the reform, unemployment has decreased signi…cantly –in 1998 the unemploy- ment rate was 6.6% and in 2002 it was 5.2%. TABLE 1. UNEMPLOYMENT IN DANISH COUNTIES (EXCL. BORNHOLM) IN 1990 - 2004, % 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 Country 9,7 11,3 12,3 8,9 6,6 5,4 5,2 6,4 Copenhagen and Frederiksberg 12,3 14,9 16 12,8 8,8 5,7 5,8 6,9 Copenhagen county 6,9 9,2 10,6 7,9 5,6 4,2 4,1 5,3 Frederiksborg county 6,6 8,4 9,7 6,9 4,8 3,7 3,7 4,5 Roskilde county 7 8,8 9,7 7,2 4,9 3,8 3,8 4,6 Western Zelland county 10,9 12 13 9,3 6,8 5,6 5,2 6,7 Storstrøms county 11,5 12,8 14,3 10,6 8,3 6,6 6,2 6,6 Funen county 11,1 12,7 14,1 8,9 6,7 6,5 6 7,3 Southern Jutland county 9,6 10,6 10,8 7,2 5,4 5,2 5,3 6,4 Ribe county 9 9,9 9,9 7 5,2 4,6 4,5 5,2 Vejle county 9,2 10,7 11,3 7,6 6 4,8 4,9 6,1 Ringkøbing county 7,7 8,4 8,8 6,4 4,8 4,1 4,1 5,3 Århus county 10,5 12 12,8 9,3 7,2 6,2 6 7,1 Viborg county 8,6 9,5 9,6 7,2 5,1 4,6 4,3 4,9 Northern Jutland county 12,9 14,5 15,1 10,7 8,1 7,2 6,8 8,7 Source: www.statistikbanken.dk However, the unemployment rates and their evolution over time di¤er be- tween Danish counties, see Table 1. -

Ronald Reagan, Louisiana, and the 1980 Presidential Election Matthew Ad Vid Caillet Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2011 "Are you better off "; Ronald Reagan, Louisiana, and the 1980 Presidential election Matthew aD vid Caillet Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Caillet, Matthew David, ""Are you better off"; Ronald Reagan, Louisiana, and the 1980 Presidential election" (2011). LSU Master's Theses. 2956. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2956 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ―ARE YOU BETTER OFF‖; RONALD REAGAN, LOUISIANA, AND THE 1980 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in The Department of History By Matthew David Caillet B.A. and B.S., Louisiana State University, 2009 May 2011 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to many people for the completion of this thesis. Particularly, I cannot express how thankful I am for the guidance and assistance I received from my major professor, Dr. David Culbert, in researching, drafting, and editing my thesis. I would also like to thank Dr. Wayne Parent and Dr. Alecia Long for having agreed to serve on my thesis committee and for their suggestions and input, as well. -

Has Polling Enhanced Representation? Unearthing Evidence from the Literary Digest Issue Polls

Studies in American Political Development, 21 (Spring 2007), 16–29. Has Polling Enhanced Representation? Unearthing Evidence from the Literary Digest Issue Polls David Karol, University of California, Berkeley How has representation changed over time in the Institutional reforms are not, however, the only United States? Has responsiveness to public opinion factors that can affect representation; technological waxed or waned among elected officials? What are change can also play a significant role. In fact, some the causes of such trends as we observe? Scholars scholars contend that the rise of scientific surveys have pursued these crucial questions in different since the 1930s has yielded more responsive govern- ways. Some explore earlier eras in search of the “elec- ment. According to this school of thought, polls toral connection”, i.e. the extent to which voters held provide recent cohorts of elected officials more accu- office-holders accountable for their actions and the rate assessments of public opinion than their prede- degree to which electoral concerns motivated poli- cessors enjoyed, which allows them to reflect their ticians’ behavior.1 Others explore the effects of insti- constituents’ views to a greater extent than the tutional changes such as the move to direct election politicians of yesteryear. Yet others doubt whether of senators or the “reapportionment revolution.”2 politicians were truly ignorant of public sentiment before the rise of the poll; nor is there much certainty regarding the level of current politicians’ understand- I thank Larry Bartels, Terri Bimes, Ben Bishin, Ben Fordham, ing of constituent opinion. Some also question John Geer, Brian Glenn, Susan Herbst, Mark Kayser, Brian Lawson, whether ignorance is at the root of elected officials’ Taeku Lee, Eileen McDonagh and Eric Plutzer for comments along frequent divergence from their constituents’ wishes. -

Appendix A: Electoral Rules

Appendix A: Electoral Rules Table A.1 Electoral Rules for Italy’s Lower House, 1948–present Time Period 1948–1993 1993–2005 2005–present Plurality PR with seat Valle d’Aosta “Overseas” Tier PR Tier bonus national tier SMD Constituencies No. of seats / 6301 / 32 475/475 155/26 617/1 1/1 12/4 districts Election rule PR2 Plurality PR3 PR with seat Plurality PR (FPTP) bonus4 (FPTP) District Size 1–54 1 1–11 617 1 1–6 (mean = 20) (mean = 6) (mean = 4) Note that the acronym FPTP refers to First Past the Post plurality electoral system. 1The number of seats became 630 after the 1962 constitutional reform. Note the period of office is always 5 years or less if the parliament is dissolved. 2Imperiali quota and LR; preferential vote; threshold: one quota and 300,000 votes at national level. 3Hare Quota and LR; closed list; threshold: 4% of valid votes at national level. 4Hare Quota and LR; closed list; thresholds: 4% for lists running independently; 10% for coalitions; 2% for lists joining a pre-electoral coalition, except for the best loser. Ballot structure • Under the PR system (1948–1993), each voter cast one vote for a party list and could express a variable number of preferential votes among candidates of that list. • Under the MMM system (1993–2005), each voter received two separate ballots (the plurality ballot and the PR one) and cast two votes: one for an individual candidate in a single-member district; one for a party in a multi-member PR district. • Under the PR-with-seat-bonus system (2005–present), each voter cast one vote for a party list. -

DA-15-132A6.Pdf

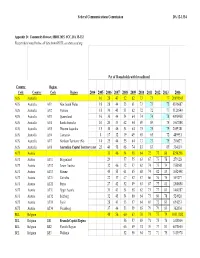

Federal Communications Commission DA 12-1334 Appendix D: Community Dataset, IBDR 2015, FCC, DA 15-132 Except where noted below, all data from OECD, see stats.oecd.org Pct of Households with broadband Country Region Code Country Code Region 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2006 AUS Australia 16 28 43 52 62 73 73 77 20695501 AUS Australia AU1 New South Wales 18 28 44 53 61 73 73 75 6816087 AUS Australia AU2 Victoria 18 30 45 51 62 72 72 77 5126540 AUS Australia AU3 Queensland 16 30 44 54 64 74 74 78 4090908 AUS Australia AU4 South Australia 10 20 33 42 54 69 69 75 1567888 AUS Australia AU5 Western Australia 15 30 46 54 64 75 75 79 2059381 AUS Australia AU6 Tasmania 8 17 32 39 49 65 65 72 489951 AUS Australia AU7 Northern Territorry (Nt) 14 25 44 55 64 73 73 79 210627 AUS Australia AU8 Australian Capital Territory (Act) 23 40 58 68 74 83 83 85 334119 AUT Austria 33 46 54 58 64 72 77 80 8254298 AUT Austria AT11 Burgenland 29 57 55 63 67 73 78 279128 AUT Austria AT12 Lower Austria 32 46 52 57 62 74 75 74 1580501 AUT Austria AT13 Vienna 45 55 61 65 68 74 82 83 1652448 AUT Austria AT21 Carinthia 22 37 47 52 57 66 76 75 559277 AUT Austria AT22 Styria 27 42 52 49 63 67 77 81 1200854 AUT Austria AT31 Upper Austria 31 43 54 58 62 73 77 81 1400287 AUT Austria AT32 Salzburg 32 45 54 60 64 73 80 78 524920 AUT Austria AT33 Tyrol 28 43 53 57 64 69 72 83 694253 AUT Austria AT34 Vorarlberg 37 44 53 59 65 79 79 83 362630 BEL Belgium 48 56 60 63 70 74 75 79 10511382 BEL Belgium BE1 Brussels Capital Region 56 57 65 71 75 76 1018804 BEL Belgium -

Public Unreason: Essays on Political Disagreement by Aaron James

Public Unreason: Essays on Political Disagreement by Aaron James Ancell Department of Philosophy Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Walter Sinnott-Armstrong, Supervisor ___________________________ Allen Buchanan ___________________________ Wayne Norman ___________________________ David Wong Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Duke University 2017 ABSTRACT Public Unreason: Essays on Political Disagreement by Aaron James Ancell Department of Philosophy Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Walter Sinnott-Armstrong, Supervisor ___________________________ Allen Buchanan ___________________________ Wayne Norman ___________________________ David Wong An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Duke University 2017 Copyright by Aaron James Ancell 2017 Abstract Why is political disagreement such a persistent and pervasive feature of contemporary societies? Many political philosophers answer by pointing to moral pluralism and the complexity of relevant non-moral facts. In Chapter 1, I argue that this answer is seriously inadequate. Drawing on work from psychology, political science, and evolutionary anthropology, I argue that an adequate explanation of political disagreement must emphasize two features of human psychology: tribalism and motivated reasoning. It is often assumed that disagreements rooted in bias and irrationality can be ignored or idealized away by philosophers developing ideal theories, that is, theories that aim to sketch the normative outlines of an ideal society. In Chapters 2 and 3, I argue that this assumption is mistaken because even ideal theories are subject to constraints, and idealizing away disagreements rooted in certain kinds of bias and irrationality violates these constraints.