Regions and Cities at a Glance 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of Umea and Region of Västerbotten

Pilot Project: “Measuring what matters to EU Citizens: Social progress in European Regions” Case study: Västerbotten - Umeå Disclaimer The information and views set out in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the European Commission. The Commission does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this study. Neither the Commission nor any person acting on the Commission’s behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained therein. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 PROFILE OF THE REGION AND DEFINITION OF THEMATIC FOCUS ..............................3 1.1 KEY SOCIOECONOMIC ASPECTS OF THE REGION .........................................................................3 1.2 THEMATIC FOCUS OF THE CASE STUDY ........................................................................................4 2 POLICIES/INITIATIVES RELATED TO THE THEMATIC AREA ..........................................5 3 USEFULNESS OF THE EU-SPI TO IMPROVE POLICYMAKING ..........................................9 3.1 APPLICATIONS (OR POTENTIAL) OF THE EU-SPI .......................................................................9 3.2 ASSESSMENT OF THE EU-SPI’S DATA ...................................................................................... 11 3.3 OTHER SOURCES OF INFORMATION ON THE THEME .................................................................. 12 4 SUGGESTED IMPROVEMENTS OF THE EU-SPI .................................................................. 12 5 -

Organisational Self-Understanding and the Strategy Process

OLOF BRUNNINGE OLOF BRUNNINGE OLOF BRUNNINGE Organisational self-understanding Organisational self-understanding and the strategy process and the strategy process Organisational Strategy dynamics in Scania and Handelsbanken self-understanding and This thesis investigates the role of organisational self-understanding in strategy processes. The concept of organisational self-understanding denotes members’ the strategy process understanding of their organisation’s identity. The study illustrates that strategy processes in companies are processes of self-understanding. During strategy ma- king, strategic actors engage in the interpretation of their organisation’s identity. Strategy dynamics in Scania and Handelsbanken This self-understanding provides guidance for strategic action while it at the same time implies understanding strategic action from the past. Organisational self-understanding is concerned with the maintenance of in- stitutional integrity. In order to achieve this, those aspects of self-understanding that have become particularly institutionalised need to develop in a continuous manner. Previous literature on strategy and organisational identity has put too much emphasis on the stability/change dichotomy. The present study shows that it is possible to maintain continuity even in times of change. Such continuity can be established by avoiding strategic action that is perceived as disruptive with regard to self-understanding and by providing interpretations of the past that make developments over time appear as free from ruptures. Self-undertsanding is hence an inherently historical phenomenon. Empirically, this study is based on in-depth case studies of strategy processes in two large Swedish companies, namely the truck manufacturer Scania and the bank Handelsbanken. In each of the companies, three strategic themes in which 027 JIBS Dissertation Series No. -

Regional Disparity and Heterogeneous Income Effects of the Euro

Better out than in? Regional disparity and heterogeneous income effects of the euro Sang-Wook (Stanley) Cho1,∗ School of Economics, UNSW Business School, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia Sally Wong2 Economic Analysis Department, Reserve Bank of Australia, Sydney, Australia February 14, 2021 Abstract This paper conducts a counterfactual analysis on the effect of adopting the euro on regional income and disparity within Denmark and Sweden. Using the synthetic control method, we find that Danish regions would have experienced small heterogeneous effects from adopting the euro in terms of GDP per capita, while all Swedish regions are better off without the euro with varying magnitudes. Adopting the euro would have decreased regional income disparity in Denmark, while the effect is ambiguous in Sweden due to greater convergence among non-capital regions but further divergence with Stockholm. The lower disparity observed across Danish regions and non-capital Swedish regions as a result of eurozone membership is primarily driven by losses suffered by high-income regions rather than from gains to low- income regions. These results highlight the cost of foregoing stabilisation tools such as an independent monetary policy and a floating exchange rate regime. For Sweden in particular, macroeconomic stability outweighs the potential efficiency gains from a common currency. JEL classification: Keywords: currency union, euro, synthetic control method, regional income disparity ∗Corresponding author. We would like to thank Glenn Otto, Pratiti Chatterjee, Scott French, Federico Masera and Alan Woodland for their constructive feedback and comments. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the Reserve Bank of Australia. -

Chapter 2. Block 1. Multi-Level Governance: Institutional and Financial Settings

PART II: OBJECTIVES FOR EFFECTIVELY INTEGRATING MIGRANTS AND REFUGEES AT THE LOCAL LEVEL 43 │ Chapter 2. Block 1. Multi-level governance: Institutional and financial settings Objective 1.Enhance effectiveness of migrant integration policy through improved vertical co-ordination and implementation at the relevant scale National level: competences for migration-related matters In Sweden, migration and integration policies are designed at the national level; however, there is no “integration code” or guidelines that all levels of government have to follow in their integration process. Since the dismantling in 2007of the former Integration Agency – created in 1998 – each ministry and government agency is responsible for integration in its particular area and integration has to be applied to all areas of policy (Bakbasel, 2012[5]). The Ministry of Justice (responsible for migration, asylum, residence permits) and the Ministry of Employment (responsible for employment, establishment, integration through work) are the two state departments responsible for most of the migration and integration policies. The Equality Ombudsman (DO) is in charge of overseeing discrimination laws. Sweden has intensified efforts to combat discrimination of foreign- born individuals since the 1990s. A comprehensive law against all kinds of discrimination was introduced in 2009. It is impossible, according to some studies, to determine whether these measures have begun to reduce discrimination (DELMI, 2017[15]). Principle of universal access to public services, with a significant exception: The guiding principle of integration politics is that the school system, welfare provisions, labour integration and health care are accessible to all societal groups on the same basis. However, this breaks with past national policies. -

Småland‑Blekinge 2019 Monitoring Progress and Special Focus on Migrant Integration

OECD Territorial Reviews SMÅLAND-BLEKINGE OECD Territorial Reviews Reviews Territorial OECD 2019 MONITORING PROGRESS AND SPECIAL FOCUS ON MIGRANT INTEGRATION SMÅLAND-BLEKINGE 2019 MONITORING PROGRESS AND PROGRESS MONITORING SPECIAL FOCUS ON FOCUS SPECIAL MIGRANT INTEGRATION MIGRANT OECD Territorial Reviews: Småland‑Blekinge 2019 MONITORING PROGRESS AND SPECIAL FOCUS ON MIGRANT INTEGRATION This document, as well as any data and any map included herein, are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. Please cite this publication as: OECD (2019), OECD Territorial Reviews: Småland-Blekinge 2019: Monitoring Progress and Special Focus on Migrant Integration, OECD Territorial Reviews, OECD Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264311640-en ISBN 978-92-64-31163-3 (print) ISBN 978-92-64-31164-0 (pdf) Series: OECD Territorial Reviews ISSN 1990-0767 (print) ISSN 1990-0759 (online) The statistical data for Israel are supplied by and under the responsibility of the relevant Israeli authorities. The use of such data by the OECD is without prejudice to the status of the Golan Heights, East Jerusalem and Israeli settlements in the West Bank under the terms of international law. Photo credits: Cover © Gabriella Agnér Corrigenda to OECD publications may be found on line at: www.oecd.org/about/publishing/corrigenda.htm. © OECD 2019 You can copy, download or print OECD content for your own use, and you can include excerpts from OECD publications, databases and multimedia products in your own documents, presentations, blogs, websites and teaching materials, provided that suitable acknowledgement of OECD as source and copyright owner is given. -

Develop Sweden! the EU Structural and Investment Funds in Sweden 2014–2020

2014 –2020 Develop Sweden! The EU Structural and Investment Funds in Sweden 2014–2020 Swedish Board The Swedish of Agriculture ESF Council © Swedish Agency for Economic and Regional Growth Production: Ordförrådet Stockholm, mars 2016 Info 0617 ISBN 978-91-87903-40-3 DEVELOP SWEDEN Develop Sweden! The European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF) provide opportunities for major investments to develop regions, individu- als and enterprises throughout Sweden. A total of SEK 67 billion (including public and/or private co-financ- ing) is to be invested in the years 2014–2020. In order for this fund- ing to have the greatest possible benefit, Sweden has agreed with the European Commission (EC) on certain priorities: • Enhance competitiveness, knowledge and innovation • Sustainable and efficient utilisation of resources for sustainable growth • Increase employment, enhance employability and improve access to the labour market In the years 2014–2020, Sweden will be participating in 27 pro- grammes financed by one of four ESIF. This brochure provides an overview of the programmes under the ESIF that concern Sweden, and the programmes in which Swedish organisations, government agencies and enterprises can participate. For those requiring more in-depth information, for example in order to seek funding, it includes references to the responsible government agencies and organisations. This brochure has been produced collaboratively by the Managing Authorities of the ESIF in Sweden. For more information about these four funds and 27 programmes, visit www.eufonder.se 1 Contents EU Structural and Investment Funds in Sweden 2014–2020 .................................................. 3 European Social Fund .............................................................................................................. 6 European Regional Development Fund ................................................................................... 8 Upper-North Sweden ............................................................................................................. -

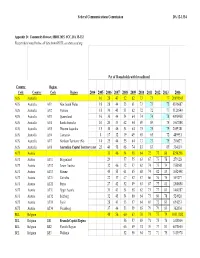

DA-15-132A6.Pdf

Federal Communications Commission DA 12-1334 Appendix D: Community Dataset, IBDR 2015, FCC, DA 15-132 Except where noted below, all data from OECD, see stats.oecd.org Pct of Households with broadband Country Region Code Country Code Region 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2006 AUS Australia 16 28 43 52 62 73 73 77 20695501 AUS Australia AU1 New South Wales 18 28 44 53 61 73 73 75 6816087 AUS Australia AU2 Victoria 18 30 45 51 62 72 72 77 5126540 AUS Australia AU3 Queensland 16 30 44 54 64 74 74 78 4090908 AUS Australia AU4 South Australia 10 20 33 42 54 69 69 75 1567888 AUS Australia AU5 Western Australia 15 30 46 54 64 75 75 79 2059381 AUS Australia AU6 Tasmania 8 17 32 39 49 65 65 72 489951 AUS Australia AU7 Northern Territorry (Nt) 14 25 44 55 64 73 73 79 210627 AUS Australia AU8 Australian Capital Territory (Act) 23 40 58 68 74 83 83 85 334119 AUT Austria 33 46 54 58 64 72 77 80 8254298 AUT Austria AT11 Burgenland 29 57 55 63 67 73 78 279128 AUT Austria AT12 Lower Austria 32 46 52 57 62 74 75 74 1580501 AUT Austria AT13 Vienna 45 55 61 65 68 74 82 83 1652448 AUT Austria AT21 Carinthia 22 37 47 52 57 66 76 75 559277 AUT Austria AT22 Styria 27 42 52 49 63 67 77 81 1200854 AUT Austria AT31 Upper Austria 31 43 54 58 62 73 77 81 1400287 AUT Austria AT32 Salzburg 32 45 54 60 64 73 80 78 524920 AUT Austria AT33 Tyrol 28 43 53 57 64 69 72 83 694253 AUT Austria AT34 Vorarlberg 37 44 53 59 65 79 79 83 362630 BEL Belgium 48 56 60 63 70 74 75 79 10511382 BEL Belgium BE1 Brussels Capital Region 56 57 65 71 75 76 1018804 BEL Belgium -

The Racist Legacy in Modern Swedish Saami Policy1

THE RACIST LEGACY IN MODERN SWEDISH SAAMI POLICY1 Roger Kvist Department of Saami Studies Umeå University S-901 87 Umeå Sweden Abstract/Resume The Swedish national state (1548-1846) did not treat the Saami any differently than the population at large. The Swedish nation state (1846- 1971) in practice created a system of institutionalized racism towards the nomadic Saami. Saami organizations managed to force the Swedish welfare state to adopt a policy of ethnic tolerance beginning in 1971. The earlier racist policy, however, left a strong anti-Saami rights legacy among the non-Saami population of the North. The increasing willingness of both the left and the right of Swedish political life to take advantage of this racist legacy, makes it unlikely that Saami self-determination will be realized within the foreseeable future. L'état suédois national (1548-1846) n'a pas traité les Saami d'une manière différente de la population générale. L'Etat de la nation suédoise (1846- 1971) a créé en pratique un système de racisme institutionnalisé vers les Saami nomades. Les organisations saamies ont réussi à obliger l'Etat- providence suédois à adopter une politique de tolérance ethnique à partir de 1971. Pourtant, la politique précédente de racisme a fait un legs fort des droits anti-saamis parmi la population non-saamie du nord. En con- séquence de l'empressement croissant de la gauche et de la droite de la vie politique suédoise de profiter de ce legs raciste, il est peu probable que l'autodétermination soit atteinte dans un avenir prévisible. 204 Roger Kvist Introduction In 1981 the Supreme Court of Sweden stated that the Saami right to reindeer herding, and adjacent rights to hunting and fishing, was a form of private property. -

The Genetic Structure of the Swedish Population

The Genetic Structure of the Swedish Population Keith Humphreys1, Alexander Grankvist1, Monica Leu1, Per Hall1, Jianjun Liu2, Samuli Ripatti3,4, Karola Rehnstro¨ m5, Leif Groop6, Lars Klareskog7, Bo Ding7, Henrik Gro¨ nberg1, Jianfeng Xu8,9, Nancy L. Pedersen1, Paul Lichtenstein1, Morten Mattingsdal10,11, Ole A. Andreassen10,12, Colm O’Dushlaine13,14, Shaun M. Purcell13,14, Pamela Sklar13,14, Patrick F. Sullivan15, Christina M. Hultman1, Juni Palmgren1,16,17, Patrik K. E. Magnusson1* 1 Department of Medical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, 2 Human Genetics Laboratory, Genome Institute of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore, 3 Institute for Molecular Medicine, Finland, FIMM, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland, 4 Public Health Genomics Unit, National Institute for Health and Welfare, Helsinki, Finland, 5 Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Wellcome Trust Genome Campus, Hinxton, United Kingdom, 6 Department of Clinical Sciences, Diabetes and Endocrinology, Lund University Diabetes Centre, Malmo¨, Sweden, 7 Institute of Environmental Medicine, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden, 8 Department of Cancer Biology and Comprehensive Cancer Center, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, United States of America, 9 Center for Cancer Genomics, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina, United States of America, 10 Institute of Clinical Medicine, Section Psychiatry, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway, 11 Sørlandet Hospital HF, Kristiansand, -

The Economical Geography of Swedish Norrland Author(S): Hans W:Son Ahlmann Source: Geografiska Annaler, Vol

The Economical Geography of Swedish Norrland Author(s): Hans W:son Ahlmann Source: Geografiska Annaler, Vol. 3 (1921), pp. 97-164 Published by: Wiley on behalf of Swedish Society for Anthropology and Geography Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/519426 Accessed: 27-06-2016 10:05 UTC Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://about.jstor.org/terms JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Swedish Society for Anthropology and Geography, Wiley are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Geografiska Annaler This content downloaded from 137.99.31.134 on Mon, 27 Jun 2016 10:05:39 UTC All use subject to http://about.jstor.org/terms THE ECONOMICAL GEOGRAPHY OF SWEDISH NORRLAND. BY HANS W:SON AHLMrANN. INTRODUCTION. T he position of Sweden can scarcely be called advantageous from the point of view of commercial geography. On its peninsula in the north-west cor- ner of Europe, and with its northern boundary abutting on the Polar world, it forms a backwater to the main stream of Continental communications. The southern boundary of Sweden lies in the same latitude as the boundary between Scotland and England, and as Labrador and British Columbia in America; while its northern boundary lies in the same latitude as the northern half of Greenland and the Arctic archipelago of America. -

Gothenburg-Borås Project

Our mission during the next few years • Decide upon the area where the new railway will run, for the Almedal-Mölnlycke and Bollebygd- Borås stretches. • Develop a detailed railway plan for the Mölnlycke- Bollebygd stretch. This entails deciding exactly where the new railway will run and how it will be designed. • Study the various options on how to proceed with the existing railway. • Conduct an inquiry regarding future rail services on the Gothenburg-Borås stretch. • Continually consult the general public, organisations and other authorities to obtain comments and knowledge. Grey = Inquiry area Gothenburg-Borås Trafikverket, SE-405 33 Gothenburg. Project Visiting address: Kruthusgatan 17 High-speed railway between Phone: +46 (0)771-921 921, Textphone: +46 (0)10-123 50 00 West Sweden’s two largest cities. www.trafikverket.se SWEDISH TRANSPORT ADMINISTRATION . JUNE 2014. PUBLIKATIONSNUMMER: 100706. PRODUCTION: PS AGENCY. PRINTING: INEKO. PHOTOGRAPHY: PAUL MATTHEW/SHUTTERSTOCK. Linking West Sweden together Why a new railway is needed Trains to the airport The Swedish Transport Administration is Gothenburg-Borås is one of Sweden’s biggest commuter The railway will pass through a tunnel underneath Stages stretches. The current single track is not adequate Göteborg Landvetter Airport. Passengers will be planning to build a new double-track high- for the great amount of travels on the stretch. Double able to get to the departures and arrivals terminals speed railway between Gothenburg and Borås. tracks built for speeds of up to 320 km/hour can halve easily from a new train station. A faster, greener and the journey time between Gothenburg and Borås and more accessible way to get to the airport than by car considerably increase the number of trains. -

Cross-Border Scandinavian Area Case Study

CIRCTER SPIN-OFF // Cross-border Scandinavian area Case study Final Report // May 2021 This CIRCTER spin-off is conducted within the framework of the ESPON 2020 Cooperation Programme, partly financed by the European Regional Development Fund. The ESPON EGTC is the Single Beneficiary of the ESPON 2020 Cooperation Programme. The Single Operation within the programme is implemented by the ESPON EGTC and co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund, the EU Member States and the Partner States, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland. This delivery does not necessarily reflect the opinions of members of the ESPON 2020 Monitoring Committee. Authors Marco Bianchi, Mauro Cordella, Pierre Merger - Tecnalia Research and Innovation, Spain Advisory group Jan Edøy - Ministry of Local Government and Modernisation, Department of Regional Development, Norway Erik Hagen, Bjørn Terje Andersen – Innlandet County Authority, Norway Marjan van Herwijnen - ESPON EGTC Information on ESPON and its projects can be found at www.espon.eu. The website provides the possibility to download and examine the most recent documents produced by finalised and ongoing ESPON projects. ISBN: 978-2-919795-97-0 © ESPON, 2020 Layout and graphic design by BGRAPHIC, Denmark Printing, reproduction or quotation is authorised provided the source is acknowledged and a copy is forwarded to the ESPON EGTC in Luxembourg. Contact: [email protected] CIRCTER SPIN-OFF // Cross-border Scandinavian area Case study Final Report // May 2021 CIRCTER SPIN-OFF // Cross-border Scandinavian