The Politicization of the Peasantry in a North Indian State: I*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Emergence of the Mahajanapadas

The Emergence of the Mahajanapadas Sanjay Sharma Introduction In the post-Vedic period, the centre of activity shifted from the upper Ganga valley or madhyadesha to middle and lower Ganga valleys known in the contemporary Buddhist texts as majjhimadesha. Painted grey ware pottery gave way to a richer and shinier northern black polished ware which signified new trends in commercial activities and rising levels of prosperity. Imprtant features of the period between c. 600 and 321 BC include, inter-alia, rise of ‘heterodox belief systems’ resulting in an intellectual revolution, expansion of trade and commerce leading to the emergence of urban life mainly in the region of Ganga valley and evolution of vast territorial states called the mahajanapadas from the smaller ones of the later Vedic period which, as we have seen, were known as the janapadas. Increased surplus production resulted in the expansion of trading activities on one hand and an increase in the amount of taxes for the ruler on the other. The latter helped in the evolution of large territorial states and increased commercial activity facilitated the growth of cities and towns along with the evolution of money economy. The ruling and the priestly elites cornered most of the agricultural surplus produced by the vaishyas and the shudras (as labourers). The varna system became more consolidated and perpetual. It was in this background that the two great belief systems, Jainism and Buddhism, emerged. They posed serious challenge to the Brahmanical socio-religious philosophy. These belief systems had a primary aim to liberate the lower classes from the fetters of orthodox Brahmanism. -

Title Prof. First Name Pradeep Kumar Last Name Yadav Photograph

Title Prof. First Name Pradeep Last Yadav Photograph Kumar Name Designation Professor, Head & Dean Department Department of Business Administration-Faculty of Management Address (Campus) MJP Rohilkhand University, Bareilly-243006 (U.P.) India. (Residence) 45/II Suresh Sharma Nagar, Bareilly- 243006 Phone No (Campus) 0581 -2523784 (Residence)optional 0581-2525339 Mobile 9412293114 Fax 0581 -2528384 Email [email protected] Web-Page Education Subject Institution Year Details Ph.D(Business MD University, Rohtak 1984 Thesis topic: Consumer attitude Administration) towards tonic- A comparative study of a cross section of doctors and non-doctors MBA MD University, Rohtak 1979 Subjects: Management B. Pharm Sagar University, Sagar 1977 Subjects: Pharm. Sciences Career Profile Organisation / Institution Designation Duration Role MD University, Rohtak Lecturer 1979-1987 Teaching & Research Department of Business Reader 1987-1995 Teaching & Research Administration, MJP Rohilkhand University, Bareilly Department of Business Professor 1995-Till date Teaching & Research Administration, MJP Rohilkhand University, Bareilly Department of Business Head 1989-2008 Teaching, Research & Administration, MJP 2011-Till date Administration Rohilkhand University, Bareilly Faculty of Management, MJP Dean 1989-2003 Teaching, Research & Rohilkhand University, 2006-2008 Administration Bareilly 2011-Till date MJP Rohilkhand University, Pro-Vice Chancellor 2008-2010 Administration Bareilly Research Interests / Specialization Business Policy and Marketing Teaching -

Custom, Law and John Company in Kumaon

Custom, law and John Company in Kumaon. The meeting of local custom with the emergent formal governmental practices of the British East India Company in the Himalayan region of Kumaon, 1815–1843. Mark Gordon Jones, November 2018. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University. © Copyright by Mark G. Jones, 2018. All Rights Reserved. This thesis is an original work entirely written by the author. It has a word count of 89,374 with title, abstract, acknowledgements, footnotes, tables, glossary, bibliography and appendices excluded. Mark Jones The text of this thesis is set in Garamond 13 and uses the spelling system of the Oxford English Dictionary, January 2018 Update found at www.oed.com. Anglo-Indian and Kumaoni words not found in the OED or where the common spelling in Kumaon is at a great distance from that of the OED are italicized. To assist the reader, a glossary of many of these words including some found in the OED is provided following the main thesis text. References are set in Garamond 10 in a format compliant with the Chicago Manual of Style 16 notes and bibliography system found at http://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org ii Acknowledgements Many people and institutions have contributed to the research and skills development embodied in this thesis. The first of these that I would like to acknowledge is the Chair of my supervisory panel Dr Meera Ashar who has provided warm, positive encouragement, calmed my panic attacks, occasionally called a spade a spade but, most importantly, constantly challenged me to chart my own way forward. -

Curriculum-Vitae

Curriculum-Vitae Mahendra Singh Asst. Professor, ITHM, Bundelkhand University Jhansi (UP) Contact no.: +918400659099 E-mail: [email protected] PROFESSIONAL QUALIFICATIONS: *Pursuing Ph.D. in Hotel Management & Tourism from Bundelkhand University, Jhansi. *UGC-NET in Tourism Administration and Management in 2005 * Master in Tourism Management with 1st Div. (63%) From IGNOU India (2001-2003) * Bachelor of Hotel Management & Catering Technology with 1st Div. (67.16%), from Department of Hotel Management, MJP Rohilkhand University, Bareilly India (1996-2000). WORKING EXPERIENCE: *Working as Asst. Professor (Food Production) in Institute of Tourism & Hotel Management, Bundelkhand University, Jhansi, Uttar Pradesh, since 03 Dec 2010. * Worked as Lecturer (Food Production) in MMICT&BM (Hotel Management), Maharishi Markandeshwar University, Mullana, Ambala (Haryana) from 01 July, 2006 to 02 Dec 2010. * Worked as Chief Supervisor (Catering Service) in Indian Railway Catering and Tourism Corporation, Posted at Guntakal (AP) India from 09 Jan, 2006 to 30 May, 2006. * Worked as a Lecturer (Food Production) in the Department of Hotel Management, MJP Rohilkhand University, Bareilly, India from 01Sep, 2000 to 05 Jan, 2006. PROFESSIONAL TRAININGS: * One Month Training in Motel Polaris, Roorkee India (UP) in BHM 1st year * Three Months Training in WG Mughal Sheraton, Agra India (UP) in BHM 2nd year * 22 Weeks Industrial Training in WG Mughal Sheraton, Agra India (UP) in BHM 3rd Year DISSERTATION: * “A Study about Spices and Herbs & their significant application in Indian Cookery” in BHM&CT 3rd year. * “Matching Food & Wine” in BHM&CT Final Year * “Indian Ethnic Cuisine: A Promotional Tool for Marketing a Tourism Product” in MTM Final Year in 2003. -

The 16 Mahajanapadas Mahajanapadas Capitals Locations Covering the Region Between Kabul and Rawalpindi in North Gandhara Taxila Western Province

The 16 Mahajanapadas Mahajanapadas Capitals Locations Covering the region between Kabul and Rawalpindi in North Gandhara Taxila Western Province. Kamboja Rajpur Covering the area around the Punch area in Kashmir Covering modern Paithan in Maharashtra; on the bank of Asmaka Potana River Godavari Vatsa Kaushambi Covering modern districts of Allahabad and Mirzapur Avanti Ujjain Covering modern Malwa (Ujjain) region of Madhya Pradesh. Located in the Mathura region at the junction of the Uttarapath Surasena Mathura & Dakshinapath Chedi Shuktimati Covering the modern Budelkhand area Modern districts of Deoria, Basti, Gorakhapur in eastern Uttar Maila Kushinara, Pawa Pradesh. Later merged into Maghada Kingdom Covering the modern Haryana and Delhi area to the west of Kurus Hastinapur/Indraprastha River Yamuna Matsya Virat Nagari Covering the area of Alwar, Bharatpur and Jaipur in Rajasthan Located to the north of the River Ganga in Bihar. It was the Vajjis Vaishali seat of united republic of eight smaller kingdoms of which Lichhavis, Janatriks and Videhas were also members. Covering the modern districts of Munger and Bhagalpur in Anga Champa Bihar. The Kingdoms were later merged by Bindusara into Magadha. Kashi Banaras Located in and around present day Varanasi in Uttar Pradesh. Covering the present districts of Faizabad, Gonda, Bahraich, Kosala Shravasti etc. Covering modern districts of Patna, Gaya and parts of Magadga Girivraja/Rajgriha Shahabad. Ahichhatra (W. Present day Rohilkhand and part of Central Doab in Uttar Panchala Panchala), Pradesh. Kampilya (S. Panchala) Alexander Invasion • Alexander marched to India through the Khyber Pass in 326 BC • His advance was checked on the bank of the Beas because of the mutiny of his soldiers • In 325 BC, he began his homeguard journey. -

[email protected] MA, M.PHIL, PH.D in History

Prof. Narayan Singh Rao Assistant Professor Contact Details: Mob. No. 9828560739 Email ID:- [email protected] Academic Qualification: MA, M.PHIL, PH.D in History (JNU) Positions Held: Work Experience (Employment History) : 1. From January 6, 1988 to July 5,1990 received ICHR Junior Research Fellowship at the Centre for Historical Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi on my doctoral thesis “Rural Economy and Society of the South Eastern Rajasthan during the Eighteenth Century”. 2. From July 6, 1990 to July 5, 1991 received Senior Research Fellowship of ICHR at the CHS/SSS, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. 3. Worked as Research Assistant from September 16, 1991 to May 17, 1992 at the Centre for the Study of the Regional Development, School of social Sciences (Jawaharlal Nehru University -New Delhi) under Professor Sukhdeo Thorat (The former UGC Chairman and Chairman, ICSSR, New Delhi) on a Central Water Commission sponsored Project entitled “Dr. B. R Ambedkar and the Development of Indian Rivers”. 4. From May 18, 1992 to December 14, 1992 worked as Research Associate in the UGC sponsored project entitled “Historical Atlas of the Northern Routes of Indian subcontinent 1550-1850 AD under the direction of Professor Moonis Raza (The former Vice Chancellor of Delhi University & Chairman of ICSSR) at CSRD/SSS/JNU New Delhi. 5. Awarded Post-Doctoral Fellowship by the Indian Council of Historical Research, New Delhi at the Centre for Historical Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University New Delhi on March 3, 1993 to work on project “The Country Town Network in the South-Eastern Rajasthan during the Eighteenth Century" under the guidance of Prof. -

Medicinal Angiosperms Diversity of Rohilkhand Region (U.P.) to Cure Some Common Human Diseases

MEDICINAL ANGIOSPERMS DIVERSITY OF ROHILKHAND REGION (U.P.) TO CURE SOME COMMON HUMAN DISEASES Beena kumari1 1Angiosperms Taxonomy Laboratory, Department of Botany, Hindu College, Moradabad.244001(U.P.) Abstract Medicinal plants play an important role in human life from ancient times. Rohilkhand region is rich in the plant diversity and the plants are used for treatment of various diseases. This study showed that many people in the studied parts still continue to depend on medicinal plants at least for the treatment of primary healthcare. The investigation revealed that, the traditional healers used 104 species of angiosperms belonging to 49 families to treat various human diseases. Majority of herbs (48) were used followed by trees (22) and shrubs (20). A total of 15 species (3 trees, 3 shrubs, 7 herbs and 2 climber) have been identified for future monitoring, which are important from conservation point of view. Keywords: Medicinal Angiosperms, Human diseases, Rohilkhand region I. INTRODUCTION India is one of the twelve mega-biodiversity countries of the world having rich vegetation with a wide variety of plants with medicinal value. There are more than two thousand five hundred plant species in India having documented medicinal value (Verma & Chauhan, 2006). These medicinal plants and their raw materials are used in the prevention, treatment and cure of health disorders by rural people of India. Generally they have a strong belief in the efficacy and success of wild plants. They collect and preserve locally available wild plant species. They often use their own herbal system to cure several diseases or ailments (Punjwani & Patel, 2006). -

Public Notice Dated: 12 May 2021

(उ楍चतर शिक्षा विभाग, शिक्षा मंत्रालय, भारत सरकार के तहत एक िायत्त संगठन) (An Autonomous Organization under the Department of Higher Education, Ministry of Education, GoI) Public Notice Dated: 12 May 2021 Mahatma Jyotiba Phule Rohilkhand University, Bareilly, Uttar Pradesh to admit candidates on the basis of the score of Uttar Pradesh Combined Entrance Test (UPCET) 2021, for the academic year 2021-22 It is hereby informed that Mahatma Jyotiba Phule Rohilkhand University, Bareilly has decided to admit candidates to the courses offered by it, as follows: I. On the basis of the score obtained by the candidates in the Uttar Pradesh Combined Entrance Test (UPCET)- 2021 conducted by the National Testing Agency. (NTA). Admission to the first year of the following courses: • Bachelor of Pharmacy (B. Pharm). • Bachelor of Hotel Management and Catering Technology (BHMCT) • Master of Computer Applications (MCA) • Master of Business Administration (MBA) Admission to the second year of the following courses (Lateral Entry): • Bachelor of Pharmacy (B. Pharm). • Bachelor of Technology (B.Tech.) II. On the basis of the score obtained by the candidates in the Joint Entrance Exam- JEE(Main) 2021 conducted by National Testing Agency (NTA): • Admission to B. Tech course. Eligibility, Scheme/duration/timings/medium/fee of examination, intake, reservation of seats, exam cities, important dates, admission procedure etc., relating to the exam are contained in the Information Bulletin hosted on www.nta.ac.in and on https://upcet.nta.nic.in and on https://jeemain.nta.nic.in Registration of candidates for appearing in UPCET -2021 is in progress. -

Indian HISTORY

Indian HISTORY AncientIndia PRE-HISTORICPERIOD G The Mesolithic people lived on hunting, fishing and food-gathering. At a later G The recent reported artefacts from stage, they also domesticated animals. Bori in Maharashtra suggest the appearance of human beings in India G The people of the Palaeolithic and around 1.4 million years ago. The early Mesolithic ages practised painting. man in India used tools of stone, G Bhimbetka in Madhya Pradesh, is a roughly dressed by crude clipping. striking site of pre-historic painting. G This period is therefore, known as the Stone Age, which has been divided into The Neolithic Age The Palaeolithic or Old Stone Age (4000-1000 BC) The Mesolithic or Middle Stone Age G The people of this age used tools and The Neolithic or New Stone Age implements of polished stone. They particularly used stone axes. The Palaeolithic Age G It is interesting that in Burzahom, (500000-9000 BC) domestic dogs were buried with their masters in their graves. G Palaeolithic men were hunters and food G First use of hand made pottery and gatherers. potter wheel appears during the G They had no knowledge of agriculture, Neolithic age. Neolithic men lived in fire or pottery; they used tools of caves and decorated their walls with unpolished, rough stones and lived in hunting and dancing scenes. cave rock shelters. G They are also called Quartzite men. The Chalcolithic Age G Homo Sapiens first appeared in the (4500-3500 BC) last phase of this period. The metal implements made by them G This age is divided into three phases were mostly the imitations of the stone according to the nature of the stone forms. -

Mountain, Water, Rock

3 Earlier Times An excellent example of the power of the Himalayan place of Kedarnath as a whole is fictional, found in a short detective story written in Bengali by Satyajit Ray (2000) and translated into English by Gopa Majumdar: “Crime in Kedarnath.” Ray wrote these stories as didactic travelogues about different regions in South Asia that educated younger readers about cultural diversity and history. While fictional, the stories skillfully and accurately portray the worldview and mores of his mid-twentieth-century, middle-class Bengali audience, who over the last century and a half have constituted one of the core visitor groups to Uttarakhand. In this episode the crime-solving trio of Feluda Mitter, Lalmohan Babu, and Feluda’s nephew Tapesh are drawn to Kedarnath on a case and are speaking with a fellow Bengali they meet on the journey. He says to them: “I have been to Kedar and Badri twenty-three times. It’s got nothing to do with religious devotion. I go back just to look at their natural beauty. If I didn’t have a family, I’d quite happily live there. I have also been to Jamunotri, Gangotri, Gomukh, Panchakedar, and Vasukital. Allow me to introduce myself. I am Makhanlal Majumdar.” Feluda said, “Namaskar” and introduced us. “Very pleased to meet you,” said Mr. Majumdar. “A lot of people are going to all these places now, thanks to road transport. They are not pilgrims, they are picnickers. But, of course, buses and taxis can do nothing to spoil the glory of the Himalayas. The scenic beauty is absolutely incredible.” (Ray 2000, 305) Yet as the story continues it strikes a different tone: Ramwara [Rambara, the midway point between Gaurikund and Kedarnath] was at a height of 2500 meters. -

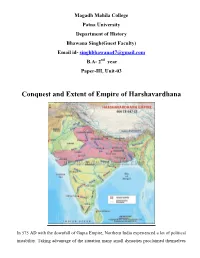

Conquest and Extent of Empire of Harshavardhana

Magadh Mahila College Patna University Department of History Bhawana Singh(Guest Faculty) Email id- [email protected] B.A- 2nd year Paper-III, Unit-03 Conquest and Extent of Empire of Harshavardhana In 575 AD with the downfall of Gupta Empire, Northern India experienced a lot of political instability. Taking advantage of the situation many small dynasties proclaimed themselves independent. War of territorial expansion broke out among various dynasties, Pushyabhuti dynasty of Thaneshwar was one among them. By early 6th and mid of 7th century the Vardhana or Pushyabhuti Dynasty became the most powerful political power in North India. The most significant ruler of Vardhana dynasty was Harshvardhana. He made an effort to bring political unity in North India and was also successful in his initiative. The dynasty got its name from the founder Pushyabhuti. We get to know about this dynasty from Harshacharita written by Bana Bhatta. There is no authentic information related to origin of Pushyabhuti Dynasty. It is believed that they were feudal lord or court ministers of the Guptas. Taking advantage of inefficient powers, Vardhanas extended their power over East Punjab (Haryana) and declared Thaneshwar as their capital. Information about Harshavardhana’s ancestry have been found from the incriptions of Madhuban and Banskheda and from the seals found in Sonepath and Nalanda. There is no information about Pushyabhuti in any historical evidences except for the Harshacharita but the names of other 4 rulers who existed before Harshvardhana namely Narvardhana (505-530 AD), Rajyavardhana (530-555 AD), Adityavardhana (555-580 AD), and Prabhakarvardhana(580-605 AD) has been found. -

Administrative Atlas, Uttaranchal

CENSUS OF INDIA 2001 UTTARANCHAL ADMINISTRATIVE ATLAS DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS UTTAR PRADESH & UTTARANCHAL The maps included in this publication are based upon Survey of India map with the permission of the Surveyor General of India. The territorial waters of India extend into the sea to a distance of twelve nautical miles measured from the appropriate base line (applicable to India map only). The interstate boundaries between Arunachal Pradesh, Assam and Meghalaya shown in this publication are as interpreted from the North-Eastern Areas (Reorganisation) Act, 1971 but have yet to be verified (applicable to India map only). The state boundaries between Uttaranchal & Uttar Pradesh, Bihar & Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh & Madhya Pradesh have not been verified by government concerned. © Government of India, Copyright 2006. Data Product Number 05-008-2001 - Cen-Atlas (ii) FOREWORD "Few people realize, much less appreciate, that apart from Survey of India and Geological Survey, the Census of India has been perhaps the largest single producer of maps of the Indian sub-continent" - this is an observation made by Dr. Ashok Mitra, an illustrious Census Commissioner of India in 1961. The statement sums up the contribution of Census Organisation which has been working in the field of mapping in the country. The Census Commissionarate of India has been working in the field of cartography and mapping since 1872. A major shift was witnessed during Census 1961 when the office had got a permanent footing. For the first time, the census maps were published in the form of 'Census Atlases' in the decade 1961-71 . Alongwith the national volume, atlases of states and union territories were also published.