Mountain, Water, Rock

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Emergence of the Mahajanapadas

The Emergence of the Mahajanapadas Sanjay Sharma Introduction In the post-Vedic period, the centre of activity shifted from the upper Ganga valley or madhyadesha to middle and lower Ganga valleys known in the contemporary Buddhist texts as majjhimadesha. Painted grey ware pottery gave way to a richer and shinier northern black polished ware which signified new trends in commercial activities and rising levels of prosperity. Imprtant features of the period between c. 600 and 321 BC include, inter-alia, rise of ‘heterodox belief systems’ resulting in an intellectual revolution, expansion of trade and commerce leading to the emergence of urban life mainly in the region of Ganga valley and evolution of vast territorial states called the mahajanapadas from the smaller ones of the later Vedic period which, as we have seen, were known as the janapadas. Increased surplus production resulted in the expansion of trading activities on one hand and an increase in the amount of taxes for the ruler on the other. The latter helped in the evolution of large territorial states and increased commercial activity facilitated the growth of cities and towns along with the evolution of money economy. The ruling and the priestly elites cornered most of the agricultural surplus produced by the vaishyas and the shudras (as labourers). The varna system became more consolidated and perpetual. It was in this background that the two great belief systems, Jainism and Buddhism, emerged. They posed serious challenge to the Brahmanical socio-religious philosophy. These belief systems had a primary aim to liberate the lower classes from the fetters of orthodox Brahmanism. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Acknowledgements xi Foreword xii I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY XIV II. INTRODUCTION 20 A. The Context of the SoE Process 20 B. Objectives of an SoE 21 C. The SoE for Uttaranchal 22 D. Developing the framework for the SoE reporting 22 Identification of priorities 24 Data collection Process 24 Organization of themes 25 III. FROM ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT TO SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT 34 A. Introduction 34 B. Driving forces and pressures 35 Liberalization 35 The 1962 War with China 39 Political and administrative convenience 40 C. Millennium Eco System Assessment 42 D. Overall Status 44 E. State 44 F. Environments of Concern 45 Land and the People 45 Forests and biodiversity 45 Agriculture 46 Water 46 Energy 46 Urbanization 46 Disasters 47 Industry 47 Transport 47 Tourism 47 G. Significant Environmental Issues 47 Nature Determined Environmental Fragility 48 Inappropriate Development Regimes 49 Lack of Mainstream Concern as Perceived by Communities 49 Uttaranchal SoE November 2004 Responses: Which Way Ahead? 50 H. State Environment Policy 51 Institutional arrangements 51 Issues in present arrangements 53 Clean Production & development 54 Decentralization 63 IV. LAND AND PEOPLE 65 A. Introduction 65 B. Geological Setting and Physiography 65 C. Drainage 69 D. Land Resources 72 E. Soils 73 F. Demographical details 74 Decadal Population growth 75 Sex Ratio 75 Population Density 76 Literacy 77 Remoteness and Isolation 77 G. Rural & Urban Population 77 H. Caste Stratification of Garhwalis and Kumaonis 78 Tribal communities 79 I. Localities in Uttaranchal 79 J. Livelihoods 82 K. Women of Uttaranchal 84 Increased workload on women – Case Study from Pindar Valley 84 L. -

Study of Glaciers in Himalaya (IHR): Observations and Assessments (Himalayan Glaciological Programme)

Study of Glaciers in Himalaya (IHR): Observations and Assessments (Himalayan Glaciological Programme) Dwarika P. DOBHAL dobhal.dp@gmail,com National Correspondent, India for WGMS Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology (An Autonomous Institute of DST, Govt. of India) Dehra Dun The Himalaya Structurally, Geologically, Ecologically and Climatically the most Diverse Region on Earth. 1. Greater Himalaya 2. Lesser Himalaya 3. Shivalik 1 2 I N D I A 3 Greater Himalaya Lesser Himalaya Shivalik Tropical Temperate Alpine Altitude Upto 1300 m a.s.l 1300 m ‐ < 3500 m a.s.l. >3500 m a.s.l. Precipitation Rainfall (1000‐2500 mm) Rainfall (1000‐1500 mm) Snowfall Temperature 20 °C –30 °C 10 °C –20 °C 5 °C –10 °C Characteristics Broad Leaved/swamp Flora Coniferous Species Snow & Glaciers Glacier System‐Indian Himalayan Region (IHR) Number of Glaciers: 9575 Glacierized area : ~ 37466km2 Jammu & Kashmir Himachal Uttarakhand Sikkim INDIA Arunachal State Glaciers Area (Km2)Average Size (Km2)Glacier (%) Jammu & Kashmir 5262 29163 10. 24 61.8 Himachal Pradesh 2735 4516 3.35 8.1 Uttarakhand 968 2857 3. 87 18.1 Sikkim 449 706 1.50 8.7 Arunachal Pradesh 162 223 1.40 3.2 (Raina and Srivastava, 2008) Distribution of Glaciers number, Ice Volume and Area 70.00 30.00 66.42% Glaciers no.% Area % 26.59% 60.00 Ice Volume % 25.00 50.00 20.00 18.39% 40.00 (%) no. (%) 15.00 12.93% 30.00 12.25% 26.14% 27.49% Volume 9.21% 10.00 20.00 Glaciers 6.86% 12.82% 14.33% 5.53% 13.61% Glaciers 4.04% 4.18% 5.00 10.00 9.44% 6.87% 6.88% 4.27% 4.12% 4.45% 1.16% 0.49% 0.41% 0.57% 0.21% 0.12% -

Chardham Yatra 2020

CHAR DHAM YATRA 2020 Karnali Excursions Nepal 1 ç Om Namah Shivaya CHARDHAM YATRA 2020 Karnali Excursions, Nepal www.karnaliexcursions.com CHAR DHAM YATRA 2020 Karnali Excursions Nepal 2 Fixed Departure Dates Starts in Delhi Ends in Delhi 1. 14 Sept, 2020 28 Sept, 2020 2. 21 Sept, 2020 5 Oct, 2020 3. 28 Sept, 2020 12 Oct, 2020 India is a big subject, with a diversity of culture of unfathomable depth, and a long Yatra continuum of history. India offers endless opportunities to accumulate experiences Overview: and memories for a lifetime. Since very ancient >> times, participating in the Chardham Yatra has been held in the highest regard throughout the length and breadth of India. The Indian Garhwal Himalayas are known as Dev-Bhoomi, the ‘Abode of the Gods’. Here is the source of India’s Holy River Ganges. The Ganges, starting as a small glacial stream in Gangotri and eventually travelling the length and breadth of India, nourishing her people and sustaining a continuum of the world’s most ancient Hindu Culture. In the Indian Garhwal Himalayas lies the Char Dham, 4 of Hinduism’s most holy places of pilgrimage, nestled in the high valleys of the Himalayan Mountains. Wearing the Himalayas like a crown, India is a land of amazing diversity. Home to more than a billion people, we will find in India an endless storehouse of culture and tradition amidst all the development of the 21st century! CHAR DHAM YATRA 2020 Karnali Excursions Nepal 3 • A complete darshan of Char Dham: Yamunotri, Trip Gangotri, Kedharnath and Badrinath. -

The Politicization of the Peasantry in a North Indian State: I*

The Politicization of the Peasantry in a North Indian State: I* Paul R. Brass** During the past three decades, the dominant party in the north Indian state of Uttar Pradesh (U. P.), the Indian National Congress, has undergone a secular decline in its support in state legislative assembly elections. The principal factor in its decline has been its inability to establish a stable basis of support among the midle peasantry, particularly among the so-called 'backward castes', with landholdings ranging from 2.5 to 30 acres. Disaffected from the Congress since the 1950s, these middle proprietary castes, who together form the leading social force in the state, turned in large numbers to the BKD, the agrarian party of Chaudhuri Charan Singh, in its first appearance in U. P. elections in 1969. They also provided the central core of support for the Janata party in its landslide victory in the 1977 state assembly elections. The politicization of the middle peasantry in this vast north Indian province is no transient phenomenon, but rather constitutes a persistent factor with which all political parties and all governments in U. P. must contend. I Introduction This articlet focuses on the state of Uttar Pradesh (U. P.), the largest state in India, with a population of over 90 million, a land area of 113,000 square miles, and a considerable diversity in political patterns, social structure, and agricul- tural ecology. My purpose in writing this article is to demonstrate how a program of modest land reform, designed to establish a system of peasant proprietorship and reenforced by the introduction of the technology of the 'green revolution', has, in the context of a political system based on party-electoral competition, enhanced the power of the middle and rich peasants. -

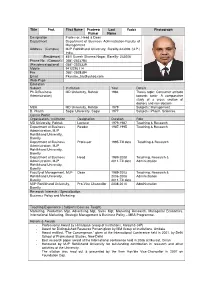

Title Prof. First Name Pradeep Kumar Last Name Yadav Photograph

Title Prof. First Name Pradeep Last Yadav Photograph Kumar Name Designation Professor, Head & Dean Department Department of Business Administration-Faculty of Management Address (Campus) MJP Rohilkhand University, Bareilly-243006 (U.P.) India. (Residence) 45/II Suresh Sharma Nagar, Bareilly- 243006 Phone No (Campus) 0581 -2523784 (Residence)optional 0581-2525339 Mobile 9412293114 Fax 0581 -2528384 Email [email protected] Web-Page Education Subject Institution Year Details Ph.D(Business MD University, Rohtak 1984 Thesis topic: Consumer attitude Administration) towards tonic- A comparative study of a cross section of doctors and non-doctors MBA MD University, Rohtak 1979 Subjects: Management B. Pharm Sagar University, Sagar 1977 Subjects: Pharm. Sciences Career Profile Organisation / Institution Designation Duration Role MD University, Rohtak Lecturer 1979-1987 Teaching & Research Department of Business Reader 1987-1995 Teaching & Research Administration, MJP Rohilkhand University, Bareilly Department of Business Professor 1995-Till date Teaching & Research Administration, MJP Rohilkhand University, Bareilly Department of Business Head 1989-2008 Teaching, Research & Administration, MJP 2011-Till date Administration Rohilkhand University, Bareilly Faculty of Management, MJP Dean 1989-2003 Teaching, Research & Rohilkhand University, 2006-2008 Administration Bareilly 2011-Till date MJP Rohilkhand University, Pro-Vice Chancellor 2008-2010 Administration Bareilly Research Interests / Specialization Business Policy and Marketing Teaching -

The Social Context of Nature Conservation in Nepal 25 Michael Kollmair, Ulrike Müller-Böker and Reto Soliva

24 Spring 2003 EBHR EUROPEAN BULLETIN OF HIMALAYAN RESEARCH European Bulletin of Himalayan Research The European Bulletin of Himalayan Research (EBHR) was founded by the late Richard Burghart in 1991 and has appeared twice yearly ever since. It is a product of collaboration and edited on a rotating basis between France (CNRS), Germany (South Asia Institute) and the UK (SOAS). Since October 2002 onwards, the German editorship has been run as a collective, presently including William S. Sax (managing editor), Martin Gaenszle, Elvira Graner, András Höfer, Axel Michaels, Joanna Pfaff-Czarnecka, Mona Schrempf and Claus Peter Zoller. We take the Himalayas to mean, the Karakorum, Hindukush, Ladakh, southern Tibet, Kashmir, north-west India, Nepal, Sikkim, Bhutan, and north-east India. The subjects we cover range from geography and economics to anthropology, sociology, philology, history, art history, and history of religions. In addition to scholarly articles, we publish book reviews, reports on research projects, information on Himalayan archives, news of forthcoming conferences, and funding opportunities. Manuscripts submitted are subject to a process of peer- review. Address for correspondence and submissions: European Bulletin of Himalayan Research, c/o Dept. of Anthropology South Asia Institute, Heidelberg University Im Neuenheimer Feld 330 D-69120 Heidelberg / Germany e-mail: [email protected]; fax: (+49) 6221 54 8898 For subscription details (and downloadable subscription forms), see our website: http://ebhr.sai.uni-heidelberg.de or contact by e-mail: [email protected] Contributing editors: France: Marie Lecomte-Tilouine, Pascale Dollfus, Anne de Sales Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, UPR 299 7, rue Guy Môquet 94801 Villejuif cedex France e-mail: [email protected] Great Britain: Michael Hutt, David Gellner, Ben Campbell School of Oriental and African Studies Thornhaugh Street, Russell Square London WC1H 0XG U.K. -

ICPR Fax: 0522-2392636 Phone No

Gram : ICPR Fax: 0522-2392636 Phone No. 0522-2392636 E-Mail : [email protected] Central Library Accession Register 3/9,Vipul Khand,Gomti Nagar Lucknow - 226010 U.P Acc. No. Title Author Publisher Year 0001 The Critic As Leavis,F R Chatto & Windus,London 1982 Anti-philosopher 2 Philosophy, Literature Nasir,S H Jeddah, Hodder & Stoughton,- 1982 And Fine Arts 3 Charector of Mind Mcginn,Colin Oxford Uni Press,- 1982 4 Claim of Reason Cavell,Stanley Oxford Uni Press,- 1979 0004 The Claim of Reason Cavell,Stanley Oxford Uni Press , Delhi,, 1979 5 ISLAM THE IDEA DIGWY,EL;Y,S Oxford & IBH Pub,N.Delhi 1982 RELIGION 6 Selfless Persons Collins,Steven Cambridge University Press,- 1982 7 Thought And Action Hampshire,Stuart Chatto & Windus,London 1982 8 Pluto's Republic Medawar,Perer Oxford Uni Press,- 1982 9 Acomparative Study Tambyah,T I Indian Book Gallery,Delhi 1983 Of hinduism, Budhism 10 The Moral Prism Emmet,Dorothy Macmillan,London 1979 11 Dictionary Of Islam Hughes,T P Cosmo Publication,New Delhi 1982 12 The Mythology Of Bailey,Grey Oxford Uni Press,- 1983 Brahma 13 Identity And Essence Brody,Baruch A Princeton University Press,Princeton And Oxford 1980 14 The Greeks On Taylor,C C.w.;Gosling,J C.b. Clarendon Press,Oxford 1982 Pleasure 15 The Varieties of Gareth,Evans Oxford U Press,London 1982 Reference 16 Concept of Indentity Hirsch,Eli Oxford University Press,New York 1982 17 Essays On Bentham Hart,H L.a. Clarendon Press,Oxford 1982 18 Marxism And Law Collins,Hugh Clarendon Press,Oxford 1982 19 Montaigne : Essays Maclean,Ian;Mefarlane,I D Clarendon Press,Oxford 1982 On Memory of Richard Sayce 20 Legal Right And Maccormick,Neil Clarendon Press,Oxford 1982 Social Democracy:Essays In Legal And Political Philosophy 21 Mar'x Social Theory Carver,Tarrell Oxford Uni Press,- 1982 22 The Marxist Hudson,Wayne Macmillan,London 1982 Philosophy Of Ernst Bloch 23 Basic Problems of Heidegger,Martin Indiana University Press,Bloomington 1982 Phenomenology 24 In Search of The Erasmus,Charles J The Free Press,London 1977 Common Good:Utopian Experiments Past And Future Acc. -

Dr. Manmohan Singh a Fit Case for Impeachment B

Social Science in Perspective EDITORIAL BOARD Chairman & Editor-in-chief Prof. (Dr.) K. Raman Pillai Editor Dr. R.K. Suresh Kumar Executive Editor Dr. P. Sukumaran Nair Associate Editors Dr. P. Suresh Kumar Adv. K. Shaji Members Prof. Puthoor Balakrishnan Nair Prof. K. Asokan Prof.V. Sundaresan Shri. V. Dethan Shri. C.P. John Dr. Asha Krishnan Managing Editor Shri. N. Shanmughom Pillai Circulation Manager Shri. V.R. Janardhanan Published by C. ACHUTHA MENON STUDY CENTRE & LIBRARY Poojappura, Thiruvananthapuram - 695 012 Tel & Fax : 0471 - 2345850 Email : [email protected] www.achuthamenonfoundation.org ii INSTRUCTION TO AUTHORS / CONTRIBUTORS Social Science in Perspective,,, a peer reviewed journal, is the quarterly journal of C. Achutha Menon (Study Centre & Library) Foundation, Thiruvananthapuram. The journal appears in English and is published four times a year. The journal is meant to promote and assist basic and scientific studies in social sciences relevant to the problems confronting the Nation and to make available to the public the findings of such studies and research. Original, un-published research articles in English are invited for publication in the journal. Manuscripts for publication (articles, research papers, book reviews etc.) in about twenty (20) typed double-spaced pages may kindly be sent in duplicate along with a CD (MS Word). The name and address of the author should be mentioned in the title page. Tables, diagram etc. (if any) to be included in the paper should be given separately. An abstract of 50 words should also be included. References cited should be carried with in the text in parenthesis. Example (Desai 1976: 180) Bibliography, placed at the end of the text, must be complete in all respects. -

Custom, Law and John Company in Kumaon

Custom, law and John Company in Kumaon. The meeting of local custom with the emergent formal governmental practices of the British East India Company in the Himalayan region of Kumaon, 1815–1843. Mark Gordon Jones, November 2018. A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The Australian National University. © Copyright by Mark G. Jones, 2018. All Rights Reserved. This thesis is an original work entirely written by the author. It has a word count of 89,374 with title, abstract, acknowledgements, footnotes, tables, glossary, bibliography and appendices excluded. Mark Jones The text of this thesis is set in Garamond 13 and uses the spelling system of the Oxford English Dictionary, January 2018 Update found at www.oed.com. Anglo-Indian and Kumaoni words not found in the OED or where the common spelling in Kumaon is at a great distance from that of the OED are italicized. To assist the reader, a glossary of many of these words including some found in the OED is provided following the main thesis text. References are set in Garamond 10 in a format compliant with the Chicago Manual of Style 16 notes and bibliography system found at http://www.chicagomanualofstyle.org ii Acknowledgements Many people and institutions have contributed to the research and skills development embodied in this thesis. The first of these that I would like to acknowledge is the Chair of my supervisory panel Dr Meera Ashar who has provided warm, positive encouragement, calmed my panic attacks, occasionally called a spade a spade but, most importantly, constantly challenged me to chart my own way forward. -

Curriculum-Vitae

Curriculum-Vitae Mahendra Singh Asst. Professor, ITHM, Bundelkhand University Jhansi (UP) Contact no.: +918400659099 E-mail: [email protected] PROFESSIONAL QUALIFICATIONS: *Pursuing Ph.D. in Hotel Management & Tourism from Bundelkhand University, Jhansi. *UGC-NET in Tourism Administration and Management in 2005 * Master in Tourism Management with 1st Div. (63%) From IGNOU India (2001-2003) * Bachelor of Hotel Management & Catering Technology with 1st Div. (67.16%), from Department of Hotel Management, MJP Rohilkhand University, Bareilly India (1996-2000). WORKING EXPERIENCE: *Working as Asst. Professor (Food Production) in Institute of Tourism & Hotel Management, Bundelkhand University, Jhansi, Uttar Pradesh, since 03 Dec 2010. * Worked as Lecturer (Food Production) in MMICT&BM (Hotel Management), Maharishi Markandeshwar University, Mullana, Ambala (Haryana) from 01 July, 2006 to 02 Dec 2010. * Worked as Chief Supervisor (Catering Service) in Indian Railway Catering and Tourism Corporation, Posted at Guntakal (AP) India from 09 Jan, 2006 to 30 May, 2006. * Worked as a Lecturer (Food Production) in the Department of Hotel Management, MJP Rohilkhand University, Bareilly, India from 01Sep, 2000 to 05 Jan, 2006. PROFESSIONAL TRAININGS: * One Month Training in Motel Polaris, Roorkee India (UP) in BHM 1st year * Three Months Training in WG Mughal Sheraton, Agra India (UP) in BHM 2nd year * 22 Weeks Industrial Training in WG Mughal Sheraton, Agra India (UP) in BHM 3rd Year DISSERTATION: * “A Study about Spices and Herbs & their significant application in Indian Cookery” in BHM&CT 3rd year. * “Matching Food & Wine” in BHM&CT Final Year * “Indian Ethnic Cuisine: A Promotional Tool for Marketing a Tourism Product” in MTM Final Year in 2003. -

The 16 Mahajanapadas Mahajanapadas Capitals Locations Covering the Region Between Kabul and Rawalpindi in North Gandhara Taxila Western Province

The 16 Mahajanapadas Mahajanapadas Capitals Locations Covering the region between Kabul and Rawalpindi in North Gandhara Taxila Western Province. Kamboja Rajpur Covering the area around the Punch area in Kashmir Covering modern Paithan in Maharashtra; on the bank of Asmaka Potana River Godavari Vatsa Kaushambi Covering modern districts of Allahabad and Mirzapur Avanti Ujjain Covering modern Malwa (Ujjain) region of Madhya Pradesh. Located in the Mathura region at the junction of the Uttarapath Surasena Mathura & Dakshinapath Chedi Shuktimati Covering the modern Budelkhand area Modern districts of Deoria, Basti, Gorakhapur in eastern Uttar Maila Kushinara, Pawa Pradesh. Later merged into Maghada Kingdom Covering the modern Haryana and Delhi area to the west of Kurus Hastinapur/Indraprastha River Yamuna Matsya Virat Nagari Covering the area of Alwar, Bharatpur and Jaipur in Rajasthan Located to the north of the River Ganga in Bihar. It was the Vajjis Vaishali seat of united republic of eight smaller kingdoms of which Lichhavis, Janatriks and Videhas were also members. Covering the modern districts of Munger and Bhagalpur in Anga Champa Bihar. The Kingdoms were later merged by Bindusara into Magadha. Kashi Banaras Located in and around present day Varanasi in Uttar Pradesh. Covering the present districts of Faizabad, Gonda, Bahraich, Kosala Shravasti etc. Covering modern districts of Patna, Gaya and parts of Magadga Girivraja/Rajgriha Shahabad. Ahichhatra (W. Present day Rohilkhand and part of Central Doab in Uttar Panchala Panchala), Pradesh. Kampilya (S. Panchala) Alexander Invasion • Alexander marched to India through the Khyber Pass in 326 BC • His advance was checked on the bank of the Beas because of the mutiny of his soldiers • In 325 BC, he began his homeguard journey.