City Narrative by Max-Valentin Robert

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Different Shades of Black. the Anatomy of the Far Right in the European Parliament

Different Shades of Black. The Anatomy of the Far Right in the European Parliament Ellen Rivera and Masha P. Davis IERES Occasional Papers, May 2019 Transnational History of the Far Right Series Cover Photo: Protesters of right-wing and far-right Flemish associations take part in a protest against Marra-kesh Migration Pact in Brussels, Belgium on Dec. 16, 2018. Editorial credit: Alexandros Michailidis / Shutter-stock.com @IERES2019 Different Shades of Black. The Anatomy of the Far Right in the European Parliament Ellen Rivera and Masha P. Davis IERES Occasional Papers, no. 2, May 15, 2019 Transnational History of the Far Right Series Transnational History of the Far Right Series A Collective Research Project led by Marlene Laruelle At a time when global political dynamics seem to be moving in favor of illiberal regimes around the world, this re- search project seeks to fill in some of the blank pages in the contemporary history of the far right, with a particular focus on the transnational dimensions of far-right movements in the broader Europe/Eurasia region. Of all European elections, the one scheduled for May 23-26, 2019, which will decide the composition of the 9th European Parliament, may be the most unpredictable, as well as the most important, in the history of the European Union. Far-right forces may gain unprecedented ground, with polls suggesting that they will win up to one-fifth of the 705 seats that will make up the European parliament after Brexit.1 The outcome of the election will have a profound impact not only on the political environment in Europe, but also on the trans- atlantic and Euro-Russian relationships. -

As Ssem N Mblé Ée N 06 Nati Iona

N° 2006 ______ ASSEMBLÉE NATIONALE CONSTITUTION DU 4 OCTOBRE 1958 QUATORZIÈME LÉGISLATURE Enregistré à la Présidence de l'Assemblée nationale le 6 juin 2019 RAPPORT FAIT AU NOM DE LA COMMISSION D’ENQUÊTE (1) sur la lutte contre les groupuscules d’extrême droite en France Mme MURIEL RESSIGUIER Présidente M. ADRIEN MORENAS Rapporteur Députés —— (1) La composition de cette commission d’enquête figure au verso de la présente page. La commission d’enquête sur la lutte contre les groupuscule d’extrême droite en France est composée de : Mme Muriel Ressiguier, présidente ; M. Adrien Morenas, rapporteur ; M. Éric Diard, Mme Émilie Guerel, M. Thomas Rudigoz, Mme Laurence Vichnievsky, vice- présidents ; MM. Christophe Arend, Meyer Habib, Mme Véronique Hammerer, M. Régis Juanico, secrétaires ; MM. Belkhir Belhaddad, Francis Chouat, Mme Coralie Dubost, MM. M’jid El Guerrab, Pascal Lavergne, Stéphane Mazars, Ludovic Mendes, Thierry Michels, Jean-Michel Mis, Pierre Morel-À-L’Huissier, Stéphane Peu, Bruno Questel, Mme Valérie Thomas, M. Jean-Louis Touraine, Mme Michèle Victory, M. Sylvain Waserman. — 3 — SOMMAIRE ___ Pages AVANT-PROPOS DE MME MURIEL RESSIGUIER, PRÉSIDENTE DE LA COMMISSION D’ENQUÊTE ...................................................................... 9 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 47 I. UNE NÉBULEUSE AUX EFFECTIFS GLOBALEMENT STABLES DONT LA PROPAGANDE BÉNÉFICIE D’UNE CHAMBRE D’ÉCHO CROISSANTE .............................................................................................................. -

Chroniques D'oropotamie

Chroniques d’Oropotamie Une nouvelle de politique-fiction par Tournesol Avant-propos Le Front National est toujours un parti protestataire. Au niveau national, il peut se présenter comme un parti neuf et proclamer qu’il est au service des classes populaires, porteur de solutions nouvelles. Que sait-on en effet de son niveau de sincérité : il n’a d’élu ni au gouvernement, ni à l’Assemblée Nationale, ni même au Sénat. Au conseil régional de Rhône-Alpes, en revanche, le FN possède un groupe de quinze élus, plus deux mis à l’écart. Au quotidien, ces élus votent, interviennent, se positionnent par rapport aux politiques proposées. En tant que collaborateur du groupe d’élus Europe Ecologie - Les Verts, je suis bien placé pour les observer. Je suis bien placé pour constater que le virage «social» dont se réclame Marine Le Pen n’a ici aucune résonance, bien que certains des conseillers régionaux comptent parmi ses proches. Ces élus sont tout simplement conformes à l’héritage de l’extrême droite auquel ils se plaisent à faire référence dans leurs interventions. Leur programme est simple : laisser-faire économique, politique sociale réduite à néant, contrôle de la culture, surenchère sécuritaire ; le fondamentalisme catholique comme boussole. Partant de ce constat, avec le soutien des élus écologistes pour qui je travaille, j’ai décidé d’écrire ce petit feuilleton en treize épisodes mettant en scène un parti imaginaire venant au pouvoir dans une région imaginaire. Ce n’est bien sûr qu’une fiction, mais... Tournesol Préface L’extrême droite avance masquée. Elle est blonde, elle est jeune, elle a le sens de la répartie. -

Mouvements Migratoires D'hier Et D'aujourd'hui En Italie

Revue européenne des migrations internationales vol. 34 - n°1 | 2018 Mouvements migratoires d’hier et d’aujourd’hui en Italie Past and Present Migration Movements in Italy Movimientos migratorios pasados y presentes en Italia Paola Corti et Adelina Miranda (dir.) Édition électronique URL : https://journals.openedition.org/remi/9565 DOI : 10.4000/remi.9565 ISSN : 1777-5418 Éditeur Université de Poitiers Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 avril 2018 ISBN : 979-10-90426-61-0 ISSN : 0765-0752 Référence électronique Paola Corti et Adelina Miranda (dir.), Revue européenne des migrations internationales, vol. 34 - n°1 | 2018, « Mouvements migratoires d’hier et d’aujourd’hui en Italie » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 01 janvier 2021, consulté le 18 mai 2021. URL : https://journals.openedition.org/remi/9565 ; DOI : https://doi.org/ 10.4000/remi.9565 © Université de Poitiers REMi Vol. 34 n ° 1 Mouvements migratoires d'hier et d'aujourd'hui en Italie Coordination : Paola Corti et Adelina Miranda Publication éditée par l’Université de Poitiers avec le concours de • InSHS du CNRS (Institut des Sciences Humaines et Sociales du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique) • MSHS (Maison des Sciences de l’Homme et de la Société de Poitiers) REMi Sommaire Vol. 34 n ° 1 Emmanuel Ma Mung et Véronique Petit ...........................................................................................7 Préface Chronique d'actualité Miguel Mellino ....................................................................................................................................11 -

Dossier CV69/GABRIAC

Alexandre Gabriac du FN aux JN Sommaire I) Un parcours politique policé …......................................................................... p 1 II) Exclu du FN ….................................................................................................... p 1 III) Création des Jeunesses Nationalistes et dogmes .............................................. p 3 IV) Alexandre Gabriac en action ............................................................................. p 5 a) Homophobie b) Battre la campagne c) Alexandre fait des études d) Alexandre voyage à l'étranger V) Les amis d'Alexandre Gabriac ............................................................................ p 8 VI) Alexandre Gabriac et la Justice ......................................................................... p 9 Bonus................................................................................................................... p 10 Annexe 1 Collectif vigilance 69 I ) Un parcours politique policé Alexandre Gabriac a fait ses armes en politiques tôt : Adhésion au FNJ, en 2004, à l'âge de treize ans • 2007 : secrétaire départemental du FNJ en Isère • 2009 : coordinateur FNJ de la circonscription Européenne Sud-Est pour la candidature de Jean-Marie Le Pen • 2009 (août) : nommé secrétaire régional du FNJ en Rhône-Alpes • 2010 : 3e sur la liste du Front national Isère aux Régionales, menée par Bruno Gollnisch • Mars 2010 : Alexandre Gabriac est élu Conseiller régional, avec plus de 15,23% des voix en Rhône-Alpes • Été 2010 : Alexandre Gabriac rend -

Skinheads, Saints, and (National) Socialists

Skinheads, Saints, and (National) Socialists An Overview of the Transnational White Supremacist Extremist Movement Daveed Gartenstein-Ross and Samuel Hodgson June 2021 FOUNDATION FOR DEFENSE OF DEMOCRACIES FOUNDATION Skinheads, Saints, and (National) Socialists An Overview of the Transnational White Supremacist Extremist Movement Daveed Gartenstein-Ross Samuel Hodgson June 2021 FDD PRESS A division of the FOUNDATION FOR DEFENSE OF DEMOCRACIES Washington, DC Skinheads, Saints, and (National) Socialists Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................................ 7 IDEOLOGIES: GLOBAL TRENDS ..................................................................................................... 8 Neo-Nazi and National Socialist Beliefs ............................................................................................................10 White Genocide and the Great Replacement ...................................................................................................10 Accelerationism ....................................................................................................................................................11 White Power Skinheads .......................................................................................................................................13 White Nationalism and White Separatism .......................................................................................................13 -

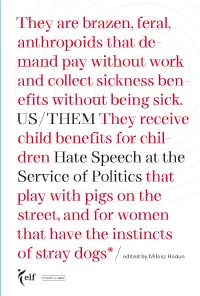

Here: on Hate Speech

They are brazen, feral, anthropoids that de- mand pay without work and collect sickness ben- efits without being sick. US / THEM They receive child benefits for chil- dren Hate Speech at the Service of Politics that play with pigs on the street, and for women that have the instincts of stray dogs * / edited by Miłosz Hodun LGBT migrants Roma Muslims Jews refugees national minorities asylum seekers ethnic minorities foreign workers black communities feminists NGOs women Africans church human rights activists journalists leftists liberals linguistic minorities politicians religious communities Travelers US / THEM European Liberal Forum Projekt: Polska US / THEM Hate Speech at the Service of Politics edited by Miłosz Hodun 132 Travelers 72 Africans migrants asylum seekers religious communities women 176 Muslims migrants 30 Map of foreign workers migrants Jews 162 Hatred refugees frontier workers LGBT 108 refugees pro-refugee activists 96 Jews Muslims migrants 140 Muslims 194 LGBT black communities Roma 238 Muslims Roma LGBT feminists 88 national minorities women 78 Russian speakers migrants 246 liberals migrants 8 Us & Them black communities 148 feminists ethnic Russians 20 Austria ethnic Latvians 30 Belgium LGBT 38 Bulgaria 156 46 Croatia LGBT leftists 54 Cyprus Jews 64 Czech Republic 72 Denmark 186 78 Estonia LGBT 88 Finland Muslims Jews 96 France 64 108 Germany migrants 118 Greece Roma 218 Muslims 126 Hungary 20 Roma 132 Ireland refugees LGBT migrants asylum seekers 126 140 Italy migrants refugees 148 Latvia human rights refugees 156 Lithuania 230 activists ethnic 204 NGOs 162 Luxembourg minorities Roma journalists LGBT 168 Malta Hungarian minority 46 176 The Netherlands Serbs 186 Poland Roma LGBT 194 Portugal 38 204 Romania Roma LGBT 218 Slovakia NGOs 230 Slovenia 238 Spain 118 246 Sweden politicians church LGBT 168 54 migrants Turkish Cypriots LGBT prounification activists Jews asylum seekers Europe Us & Them Miłosz Hodun We are now handing over to you another publication of the Euro- PhD. -

SPCJ Disponible Au Téléchargement, En Français Et En Anglais Sur This Report Can Be Downloaded in French and English At

Service de Protection de la Communauté Juive 2019 Rapport sur l’antisémitisme en France Source éléments statistiques : Ministère de l’Intérieur et SPCJ Disponible au téléchargement, en français et en anglais sur This report can be downloaded in French and English at www.antisemitisme.fr Ce rapport a été réalisé avec le soutien de la Fondation pour la Mémoire de la Shoah (FMS) RAPPORT SUR L’ANTISÉMITISME EN FRANCE EN 2019 ANTISÉMITISME EN FRANCE EN 2019 SOMMAIRE SOMMAIRE Sommaire 2 Le SPCJ 5 Eric de Rothschild – Président du SPCJ 6 Haim Korsia – Grand Rabbin de France 8 Joël Mergui – Président des Consistoires 9 Francis Kalifat – Président du Conseil Représentatif des Institutions juives de France 11 Ariel Goldmann – Président du Fonds Social Juif Unifié 13 La méthodologie utilisée 15 1. Statistiques et analyses 17 1.1 Constats et analyses 19 1.2 Tableau récapitulatif des Actes antisémites recensés en France en 2019 21 1.3 Antisémitisme en France en 2019 22 1.4 Actes antisémites recensés en France de 1998 à 2019 23 1.5 Racisme et antisémitisme en 2019 24 1.6 Répartition géographique des Actes antisémites en 2019 25 2. Extraits de la liste des actes antisémites recensés en 2019 31 3. Extraits de la liste des condamnations prononcées en 2019 49 4. Ils en parlent… 57 Les Français sont plus tolérants... mais les actes racistes augmentent 59 Par M.F. L’Obs (23/04/2019) Tribune : « La lutte contre le terrorisme ne se fera pas sans les citoyens » 61 Tribune collective Le Figaro (28/10/2019) Sondage : 1 Européen sur 4 reconnaît nourrir de l’hostilité -

Front National Et Ultras: Les Preuves D'une Amitié 13 SEPTEMBRE 2013 | PAR MARINE TURCHI Le Front National Se Réunit Ce Week-End À Marseille Pour Son Université D'été

Front national et ultras: les preuves d'une amitié 13 SEPTEMBRE 2013 | PAR MARINE TURCHI Le Front national se réunit ce week-end à Marseille pour son université d'été. À six mois des municipales, Marine Le Pen veut poursuivre son nettoyage de façade du parti et gommer son image d'extrême droite. Le FN n'aurait aucun rapport avec les JNR, le GUD, les révisionnistes, l'ultra droite et autres, affirme haut et fort sa présidente. Faux. Mediapart publie, photos à l'appui, les preuves contraires. • Comme avant chaque élection et après chaque débordement médiatisé d'un candidat frontiste, Marine Le Pen a demandé dans une note interne que ses candidats aux municipales « respectent la ligne politique du parti » et ne « se laissent pas aller à des délires personnels ou idéologiques ». À six mois des municipales, la présidente du FN veut poursuivre son nettoyage de façade du parti et gommer son image d'extrême droite. Mais cette stratégie se heurte à la porosité entre le Front national et les groupuscules de l'extrême droite la plus radicale. LIRE AUSSI • L'Œuvre française: 40 ans d'entrisme au FN PAR MARINE TURCHI • Activisme et business: l'engagement pro-Assad des proches de Le Pen PAR MARINE TURCHI • L’argent syrien d’un proche de Marine Le Pen PAR KARL LASKE ET MARINE TURCHI • Le M. sécurité du FN dans les débordements d'une manif anti-mariage pour tous PAR MARINE TURCHI • Front national: les réseaux obscurs de Marine Le Pen PAR MARINE TURCHI • Mort de Clément Méric: l'interdiction des groupes fascistes suffit-elle? PAR MARINE TURCHI Marine Le Pen a beau assurer que son parti n'a « aucun rapport avec ces groupes, qui expriment d'ailleurs régulièrement leur désapprobation à (son) égard », son vice-président, Florian Philippot, a beau répéterque « le FN n'a rien à voir avec ces personnalités radicales » et qu'il n'est « pas d'extrême droite », les faits sont têtus. -

Diversity and Contestations Over Nationalism in Europe and Canada

Palgrave Studies in European Political Sociology Diversity and Contestations over Nationalism in Europe and Canada Edited by John Erik Fossum, Riva Kastoryano, and Birte Siim Palgrave Studies in European Political Sociology Series Editors Carlo Ruzza Department of Sociology and Social Research University of Trento Trento, Italy Hans-Jörg Trenz Department of Media, Cognition and Communication University of Copenhagen Copenhagen, Denmark [email protected] Palgrave Studies in European Political Sociology addresses contemporary themes in the field of Political Sociology. Over recent years, attention has turned increasingly to processes of Europeanization and globalization and the social and political spaces that are opened by them. These pro- cesses comprise both institutional-constitutional change and new dynam- ics of social transnationalism. Europeanization and globalization are also about changing power relations as they affect people’s lives, social net- works and forms of mobility. The Palgrave Studies in European Political Sociology series addresses linkages between regulation, institution build- ing and the full range of societal repercussions at local, regional, national, European and global level, and will sharpen understanding of changing patterns of attitudes and behaviours of individuals and groups, the politi- cal use of new rights and opportunities by citizens, new conflict lines and coalitions, societal interactions and networking, and shifting loyalties and solidarity within and across the European space. We welcome pro- posals from across the spectrum of Political Sociology and Political Science, on dimensions of citizenship; political attitudes and values; political communication and public spheres; states, communities, gover- nance structure and political institutions; forms of political participation; populism and the radical right; and democracy and democratization. -

The New Front National: Still a Master Case?

WORKING PAPER SERIES Online Working Paper No. 30 (2013) The New Front National: Still a Master Case? Hans-Georg Betz This paper can be downloaded without charge from: http://www.recode.info ISSN 2242-3559 RECODE – Responding to Complex Diversity in Europe and Canada ONLINE WORKING PAPER SERIES RECODE, a research networking programme financed through the European Science Foundation (ESF), is intended to explore to what extent the processes of transnationalisation, migration, religious mobilisation and cultural differentiation entail a new configuration of social conflict in post-industrial societies - a possible new constellation labelled complex diversity . RECODE brings together scholars from across Europe and Canada in a series of scientific activities. More information about the programme and the working papers series is available via the RECODE websites: www.recode.fi www.recode.info www.esf.org/recode Series Editor: Peter A. Kraus Section 4, Workshop 4: Solidarity Beyond the Nation-State: Diversity, (In)Equalities and Crisis Title: The New Front National: Still a Master Case? Author: Hans-Georg Betz Working Paper No. 30 Publication Date of this Version: September 2013 Webpage: http://www.recode.info © RECODE, 2013 Augsburg, Germany http://www.recode.info © 2013 by Hans-Georg Betz All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit is given to the source. The views expressed in this paper do not necessarily reflect those of the RECODE Research Networking Programme or the European Science Foundation. Hans-Georg Betz University of Zurich, Switzerland [email protected] ISSN 2242-3559 Standing Committee for the Social Sciences (SCSS) Standing Committee for the Humanities (SCH) The New Front National: Still a Master Case? Hans-Georg Betz Hans-Georg Betz, author of several books, articles, and book chapters on right-wing populism in Western Europe, currently is an adjunct professor of political science at the University of Zurich, Switzerland. -

Le Petit Monde Merveilleux De L'ed Radicale Lyonnaise.Indd

Le petit monde merveilleux de l’extrême-droite radicale lyonnaise Rebeyne Les Jeunesses Le GUD Lyon Les Autonomes 3e Voie Les autres groupes Section lyonnaise des jeunes identitai- Nationalistes Section lyonnaise du GUD, créée en Lyonnais Section lyonnaise de 3e Voie, créée en présents à Lyon res, créée en février 2003, dirigée par septembre 2011, dirigée par Steven juillet 2011 par Renaud Mannheim. Branche jeunes de l’Œuvre Francaise, Section lyonnaise des Nationalistes Les intellos Damien Rieu. Bissuel. Caractéristiques : nationaliste, néona- créée en octobre 2011, dirigée par Autonomes, créée en 2010 par Nicolas Caractéristiques : ethnorégionaliste, Caractéristiques : nationaliste, anti- zi, anti-musulman, antisémite. courant Gollnisch du FN Alexandre Gabriac. André, dit Willo. anti-musulman. musulman, antisémite. Il assure notamment la formation des Caractéristiques : nationaliste, anti- Caractéristiques : nationaliste, anti- jeunes cadres nationalistes. musulman, antisémite. musulman, antisémite. Égalité et Réconciliation Créé en 2007, dirigé par Alain Soral Entre hooligans et skinheads fascistes (30 membres). (bonehead), ce groupuscule réunit une trentaine de personnes, les plus radi- Europe Identité Le Groupe Union Défense est un mou- cales et surtout les plus violentes de Issu d’Unité Radicale, dissous après vement étudiant d’extrême-droite, qui Branche jeunes de Terre et Peuple, or- l’extrême-droite lyonnaise. Les actions la tentative d’assassinat du prési- se présente aux élections universi- ganisation dirigée par Pierre Vial. Ce groupuscule se revendique ouver- Les Autonomes Lyonnais n’existent officielles se limitent pour l’instant à dent Chirac par l’un de ses militants, taires sous la vitrine « Union Défense tement fasciste, comme le montre leur pas vraiment pour l’instant, mais vu des tags le long des ponts d’autorou- Mouvement Action Sociale les Identitaires regroupent plusieurs de la Jeunesse ».