CHŪSHINGURA BETWEEN INNOVATION and ARTISTIC EXPERIMENTATION Silvia Vesco1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rethinking the Ako Ronin Debate the Religious Significance of Chushin Gishi

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 1999 26/1-2 Rethinking the Ako Ronin Debate The Religious Significance of Chushin gishi John Allen T ucker This paper suggests that the Tokugawa Confucian debate over the Ako revenge vendetta was, in part, a religious debate over the posthumous sta tus of the forty-six ronin who murdered Lord Kira Yoshinaka as an act of revenge for the sake of their deceased master, Asano Naganori. At issue in the debate was whether the forty-six ronin were chushin gishi, a notion typ ically translated as “loyal and righteous samurai. ” The paper shows, how ever, that in Tokugawa discourse the term chushin gishi had significant religious nuances. The latter nuances are traceable to a Song dynasty text, the Xingli ziyi, by Chen Beixi, which explains that zhongchen yishi (Jpn. chushin gishi) could be legitimately worshiped at shrines devoted to them. The paper shows that Beixi text was known by those involved in the Ako debate, and that the religious nuances, as well as their sociopolitical impli cations, were the crucial, albeit largely unspoken, issues in the debate.1 he paper also notes that the ronin were eventually worshiped, by none other than the Meiji emperor, and enshrined in the early-twentieth century. Also, in prewar Japan, they were extolled as exemplars of the kind of self- sacrijicing loyalism that would be rewarded, spiritually, via enshrinement at Yasukuni Shrine. Keywords: Ako ronin — chushin gishi (zhongchen yishi)—しhen Beixi — Xingli ziyi — Yamasra Soko — Bakufu —apotheosis Chushin gishi 忠、臣義 士 was the pivotal notion in the eighteenth-century controversy among Confucian scholars over the Ako 赤穂 revenge vendetta of 1703. -

Honor and Violence: Perspectives on the Akō Incident

Honor and Violence: Perspectives on the Akō Incident Megan McClory April 4, 2018 A senior thesis, submitted to the East Asian Studies Department of Brandeis University, in partial fulfillment of the Bachelor of Arts degree. Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………1 Law and Morality………………………………………………………………………………...4 Kenka Ryouseibai…………………………………………………………………………5 House Codes……………………………………………………………………………....8 Loyalty as Propaganda…………………………………...………………………………..9 Filial Piety………………………………………………………………………………13 Evolution into Legend……………………………………………………………………………15 Dissemination……………………………………………………………………………15 Audience…………………………………………………………………………………18 Akō as an Example………………………………………………………………………19 Modern Day……………………………………………………………………………...20 Sengaku-ji………………………………………………………………………………. 22 Chūshingura as a Genre………………………………………………………………… 25 Ukiyo-e………………………………………………………………………………...…25 Appeal and Extension to Non-Samurai………………………………..…………………………28 Gihei the Merchant………………………………………………………………………28 Injustice…..………………………………………………………………………………35 Amae …………………………………………………………………………………….38 Collective Honor…………………………………………………………………………41 Women in Chūshingura………………………………………………………………….44 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………….47 List of Names and Characters Adapted from David Bell Chushingura and the Floating World: The Representation of Kanadehon Chushingura in Ukiyo-e Prints Enya Hangan A young provincial noble and Lord of the castle of Hoki under the shogun Ashikaga Takauji. Asano Takuminokami Naganori, Lord of Akō in the province of Harima. -

Analecta Nipponica

5/2016 Analecta Nipponica JOURNAL OF POLISH ASSOCIATION FOR JAPANESE STUDIES Analecta Nipponica JOURNAL OF POLISH ASSOCIATIOn FOR JapanESE STUDIES 5/2016 Analecta Nipponica JOURNAL OF POLISH ASSOCIATIOn FOR JapanESE STUDIES Analecta Nipponica JOURNAL OF POLISH ASSOCIATIOn FOR JapanESE STUDIES Editor-in-Chief Alfred F. Majewicz Nicolaus Copernicus University, Toruń Editorial Board Agnieszka Kozyra University of Warsaw, Jagiellonian University in Kraków Iwona Kordzińska-Nawrocka University of Warsaw Editing in English Aaron Bryson Editing in Japanese Fujii Yoko-Karpoluk Editorial Advisory Board Moriyuki Itō Gakushūin University in Tokyo Mikołaj Melanowicz University of Warsaw Sadami Suzuki International Research Center for Japanese Studies in Kyoto Hideo Watanabe Shinshū University in Matsumoto Estera Żeromska Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań The publication was financed by Takashima Foundation Copyright© 2015 by Polish Association for Japanese Studies and Contributing Authors. ANALECTA NIPPONICA: Number 5/2015 ISSN: 2084-2147 Published by: Polish Association for Japanese Studies Krakowskie Przedmieście 26/28, 00-927 Warszawa, Poland www.psbj.orient.uw.edu.pl University of Warsaw Printers (Zakłady Graficzne UW) Order No. 1312/2015 Contents Editor’s preface ...............................................................7 ARTICLES Iijima Teruhito, 日本の伝統芸術―茶の美とその心 .............................11 English Summary of the Article Agnieszka Kozyra, The Oneness of Zen and the Way of Tea in the Zen Tea Record (Zencharoku) .............................................21 -

Schaftliches Klima Und Die Alte Frau Als Feindbild

6 Zusammenfassung und Schluss: Populärkultur, gesell- schaftliches Klima und die alte Frau als Feindbild Wie ein extensiver Streifzug durch die großstädtische Populärkultur der späten Edo-Zeit gezeigt hat, tritt darin etwa im letzten Drittel der Edo-Zeit der Typus hässlicher alter Weiber mit zahlreichen bösen, ne- gativen Eigenschaften in augenfälliger Weise in Erscheinung. Unter Po- pulärkultur ist dabei die Dreiheit gemeint, die aus dem volkstümlichen Theater Kabuki besteht, den polychromen Holzschnitten, und der leich- ten Lektüre der illustrierten Romanheftchen (gōkan) und der – etwas gehobenere Ansprüche bedienenden – Lesebücher (yomihon), die mit einem beschränkten Satz von Schriftzeichen auskamen und der Unter- haltung und Erbauung vornehmlich jener Teile der Bevölkerung dien- ten, die nur eine einfache Bildung genossen hatten. Durch umherziehen- de Leihbuchhändler fand diese Art der Literatur auch über den groß- städtischen Raum hinaus bis hin in die kleineren Landflecken und Dör- fer hinein Verbreitung. Die drei Medien sind vielfach verschränkt: Holzschnitte dienen als Werbemittel für bzw. als Erinnerungsstücke an Theateraufführungen; Theaterprogramme sind reich illustrierte kleine Holzschnittbücher; die Stoffe der Theaterstücke werden in den zahllo- sen Groschenheften in endlosen Varianten recyclet; in der Heftchenlite- ratur spielt die Illustration eine maßgebliche Rolle, die Illustratoren sind dieselben wie die Zeichner der Vorlagen für die Holzschnitte; in einigen Fällen sind Illustratoren und Autoren identisch; Autoren steuern Kurz- texte als Legenden für Holzschnitte bei. Nachdrücklich muss der kommerzielle Aspekt dieser „Volkskultur“ betont werden. In allen genannten Sparten dominieren Auftragswerke, die oft in nur wenigen Tagen erledigt werden mussten. Die Theaterbe- treiber ließen neue Stücke schreiben oder alte umschreiben beziehungs- weise brachten Kombinationen von Stücken zur Aufführung, von wel- chen sie sich besonders viel Erfolg versprachen. -

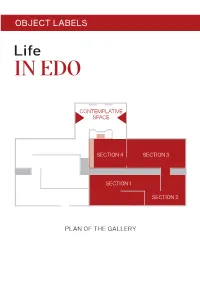

Object Labels

OBJECT LABELS CONTEMPLATIVE SPACE SECTION 4 SECTION 3 SECTION 1 SECTION 2 PLAN OF THE GALLERY SECTION 1 Travel Utagawa Hiroshige Procession of children passing Mount Fuji 1830s Hiroshige playfully imitates with children a procession of a daimyo passing Mt Fuji. A popular subject for artists, a daimyo and his entourage could make for a lively scene. During Edo, daimyo were required to travel to Edo City every other year and live there under the alternate attendance (sankin- kōtai) system. Hundreds of retainers would transport weapons, ceremonial items, and personal effects that signal the daimyo’s military and financial might. Some would be mounted on horses; the daimyo and members of his family carried in palanquins. Cat. 5 Tōshūsai Sharaku Actor Arashi Ryūzō II as the Moneylender Ishibe Kinkichi 1794 Kabuki actor portraits were one of the most popular types of ukiyo-e prints. Audiences flocked to see their favourite kabuki performers, and avidly collected images of them. Actors were stars, celebrities much like the idols of today. Sharaku was able to brilliantly capture an actor’s performance in his expressive portrayals. This image illustrates a scene from a kabuki play about a moneylender enforcing payment of a debt owed by a sick and impoverished ronin and his wife. The couple give their daughter over to him, into a life of prostitution. Playing a repulsive figure, the actor Ryūzō II made the moneylender more complex: hard-hearted, gesturing like a bully – but his eyes reveal his lack of confidence. The character is meant to be disliked by the audience, but also somewhat comical. -

Hokusai's Landscapes

$45.00 / £35.00 Thomp HOKUSAI’S LANDSCAPES S on HOKUSAI’S HOKUSAI’S sarah E. thompson is Curator, Japanese Art, HOKUSAI’S LANDSCAPES at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The CompleTe SerieS Designed by Susan Marsh SARAH E. THOMPSON The best known of all Japanese artists, Katsushika Hokusai was active as a painter, book illustrator, and print designer throughout his ninety-year lifespan. Yet his most famous works of all — the color woodblock landscape prints issued in series, beginning with Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji — were produced within a relatively short time, LANDSCAPES in an amazing burst of creative energy from about 1830 to 1836. These ingenious designs, combining MFA Publications influences from several different schools of Asian Museum of Fine Arts, Boston art as well as European sources, display the 465 Huntington Avenue artist’s acute powers of observation and trademark Boston, Massachusetts 02115 humor, often showing ordinary people from all www.mfa.org/publications walks of life going about their business in the foreground of famous scenic vistas. Distributed in the United States of America and Canada by ARTBOOK | D.A.P. Hokusai’s landscapes not only revolutionized www.artbook.com Japanese printmaking but also, within a few decades of his death, became icons of art Distributed outside the United States of America internationally. Illustrated with dazzling color and Canada by Thames & Hudson, Ltd. reproductions of works from the largest collection www.thamesandhudson.com of Japanese prints outside Japan, this book examines the magnetic appeal of Hokusai’s Front: Amida Falls in the Far Reaches of the landscape designs and the circumstances of their Kiso Road (detail, no. -

TJ and the 47 Ronin

Thomas Jefferson and the samurai spirit Tokugawa Ieyasu won the battle of Sekigahara in 1601, and he ushered into Japan several centuries of feudal rule. To celebrate his victory, Tokugawa took the title of Shogun, invited peasants to decapitate his rival and established a rigid set of laws and regulations that lasted nearly 300 years. One century after Sekigahara, Japan experienced an epic event that set the character of the nation ever after. 1 The sacrifices attendant with this tale would Tokugawa have been understood and appreciated by Thomas Jefferson. Ieyasu Approximately four decades before Jefferson’s birth, in 1701 in Edo (Tokyo) an important imperial protocol officer, Kira Kozuke-no-Suke Yoshinaka, was charged with teaching court etiquette to young nobles including Asano Takumi-no- Kami Naganori. Kira by all accounts was irascible and demanding, probably corrupt and undisputedly insulting. Then after stoically enduring this pedagogical abuse for months, Asano attacked Kira with a weapon.2 Although Kira was only slightly injured, drawing a blade inside the imperial Goaded by Kira, palace was a capital Lord Asano crime. Accordingly Kira Yoshinaka Asano was attacks with a ordered to commit seppuku.3 katana leaving a The Asano clan’s family lands in Western Honshu were forfeit. slight wound and His family and the family’s retainers were dispersed landless a scar. having acquired an economic burden they could not repay and a murderous debt of honor which custom demanded they avenge. That payback fell to 47 Asano samurai now called “ronin” or masterless warriors. Under the leadership of Oishi Kuranosuke, the clan knew full well the dilemma it faced.4 Legally the punishment for murder extended to relatives; entire families could be 1 Ishida Mistunari was the losing general at Sekigahara. -

Download ARTHIST432S Weisenfeld Semester Outline

WEEK DATE TOPIC/ASSIGNMENT 1 Jan 20 (W) Introduction: Course Overview 2 Jan 25 What is Ukiyo-e (Pictures of the Floating World)? Jenkins, Donald. “Introduction,” in Donald Jenkins, ed., The Floating World Revisited. Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press and Portland Art Museum, 1993: 3-23. Hokusai: The Suspended Threat (Section 3 (8:50-14:30) How to Make a Woodblock Print) [electronic resource], Films Media Group, 1999. Online Video available through Duke library catalogue (Search “Films on Demand”). Specialized printing techniques: http://pulverer.si.edu/node/189 Davis, Julie Nelson. “Picturing the Floating World: Ukiyo-e in Context” (Talk 50 minutes – Q&A after optional) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UQXfb6JOby0 Jan 27 Collaboration and the Ukiyo-e Quartet *Visitor: Professor Julie Nelson Davis (University of Pennsylvania) 3 Feb 1 Bordello Chic and Edo Eroticism Discussion Leaders: Seigle, Cecelia. Yoshiwara: The Glittering World of the Japanese Courtesan. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press: 1-13. Screech, Timon. “Introduction” and “Chapter 1: Erotic Images, Pornography, Shunga and Their Use,” in Sex and the Floating World, Reaktion Press, 2009: 7-38. The British Museum Shunga Exhibition: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T9eNggxOu-o&t=21 Utamaro and his Five Women, dir. Kenji Mizoguchi Feb 3 Bordello Chic and Edo Eroticism continued 4 Feb 8 The Realms of Spectacle: Kabuki and Sumo Discussion Leaders: Clark, Timothy. “Edo Kabuki in the 1780s,” in The Actor’s Image: Printmakers of the Katsukawa School. The Art Institute of Chicago, 1994: 27-48. Kominz, Laurence. “Ichikawa Danjurō V and Kabuki’s Golden Age,” in The Floating World Revisited: 63-83. -

Issue 3 Spring 2014

Issue 3 Inside this issue: Spring 2014 Editor’s Note 2 Upcoming Events 3 IAJS News: A summary of Japan-related academic events in 6 Israel Special Feature: Voices in Japanese Art Research in Israel 10 Featured Article: The Brush and the Keyboard: On Being an 13 Artist and a Researcher Collecting Japanese Erotic Art: Interview with Ofer Shagan 18 Japanese Art Collections in Israel 21 New Scholar in Focus: Interview with Reut Harari, PhD Candidate 29 at Princeton University New Publications: A selection of publications by IAJS members 32 The Israeli Association for Japanese IAJS Council 2012-2013 The Israeli Association of Studies Newsletter is a biannual Japanese Studies (IAJS) is a non publication that aims to provide Honorary President: -profit organization seeking to information about the latest Prof. Emeritus Ben-Ami encourage Japanese-related developments in the field of Japanese Shillony research and dialogue as well as Studies in Israel. (HUJI) to promote Japanese language education in Israel. We welcome submissions from IAJS Council Members: members regarding institutional news, Dr. Nissim Otmazgin (HUJI) For more information visit the publications and new researches in the Dr. Michal Daliot-Bul (UH) IAJS website at: Dr. Irit Averbuh (TAU) www.japan-studies.org Image: Itsukushima, Aki. Utagawa field of Japanese Studies. Please send Dr. Sigal Ben-Rafael Galanti Hiroshige II (1829-1869). Section of your proposals to the editor at: (Beit Berl College & HUJI) General Editor: Ms. Irit Weinberg emaki-mono, ink and colour on paper, [email protected]. Dr. Helena Grinshpun (HUJI) Language Editor: Ms. Nikki Littman 1850-1858. -

Redalyc.Ukiyo-E in the Gulbenkian Collection. a Few Examples

Bulletin of Portuguese - Japanese Studies ISSN: 0874-8438 [email protected] Universidade Nova de Lisboa Portugal Paias, Manuel Ukiyo-e in the Gulbenkian Collection. A Few Examples Bulletin of Portuguese - Japanese Studies, vol. 12, june, 2006, pp. 111-122 Universidade Nova de Lisboa Lisboa, Portugal Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=36101207 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative BPJS, 2006, 12Ukiyo-e, 111-122 in the Gulbenkian Collection. A few examples 111 UKIYO-E IN THE GULBENKIAN COLLECTION. A FEW EXAMPLES Manuel Paias The Gulbenkian Museum has around two hundred Japanese woodblock prints in its collection, acquired by Calouste Gulbenkian in the early 20th cen- tury. These prints form an interesting ensemble, focusing on the late 18th and early 19th centuries, a period commonly considered to be the finest period of Japanese printmaking. As these wonderful prints are currently unavailable for public viewing, the Bulletin sought to obtain permission to publish a small part of the collec- tion, thus enabling it to be appreciated by a wider audience. A timely and thorough study of the collection and a painstaking selection was not possible, so the present piece is nothing more than a glimpse that we hope will be extended in the near future. The first print published here (Fig. 1) represents The Lion Dance (Shishi Mai) and is from Isoda Shunei or Shun’ei (1762-1819), a distinguished member of the Katsukawa School, a renowned pupil of Katsukawa Shunshõ (1726-1793), and a major influence on two of the greatest artists of the late 18th century: Sharaku (act. -

The Development of Facial Likeness in Kabuki Actor Prints

Article The development of facial likeness in kabuki actor prints Henk J. Herwig Introduction The growing popularity of kabuki as a plebeian pastime in the seventeenth century stimulated enterprising publishers to provide the market with woodblock printed text and pictures related to the world of kabuki. Halfway this century actor critiques (hyôbanki) and illustrated play books (kyôgen bon) were issued, while theatre managers began to commission posters (banzuke), advertising their performances. These works, printed in black ink only, were at first dominated by text but gradually more illustrations of kabuki scenes and actors were inserted. The actors were mostly represented as anonymous personalities, despite the fact that the hyôbanki often described and discussed in detail the specific physical beauty and charms of popular actors. In the Genroku period (1688-1704), when kabuki experienced its Golden Age, important developments took place. ew acting styles, such as aragoto, established in Edo by the actor Ichikawa Danjûrô I (1660-1704) and wagoto, initiated in Osaka by the actor Sakata Tôjrô (1647-1709) became popular, and talented scriptwriters, such as Chikamatsu Monzaemon (1653-1725) enriched the kabuki repertory with captivating new dramas. Artists of the Torii School, known for painting illustrated theatre billboards, started in about the same period to design pictures of kabuki actors that were printed with woodblocks. This was the beginning of a unique tradition, unequalled in any other part of the world, that would flourish for almost200 years. This article describes when and how the woodblock printed actor portrait changed in the course of time from anonymous stereotypical depictions into nigao-e in which the individual actor could easily be recognized.1 To facilitate an objective comparison between faces of actors, designed in different periods, digital redrawings were used. -

La Influencia De Ichikawa En'nosuke Iii En La

VIOLETTA BRÁZHNIKOVA TSÝBIZOVA LA INFLUENCIA DE ICHIKAWA EN’NOSUKE III EN LA EVOLUCIÓN DE LOS RECURSOS ESCENOGRÁFICOS DEL TEATRO KABUKI Y SU RELACIÓN CON LA PUESTA EN ESCENA DEL TEATRO CONTEMPORÁNEO ESPAÑOL TESIS DOCTORAL DIRIGIDA POR LA DOCTORA KAYOKO TAKAGI TAKANASHI, PROFESORA TITULAR DE LENGUA Y LITERATURA DE JAPÓN DE LA UNIVERSIDAD AUTÓNOMA DE MADRID DEPARTAMENTO DE CIENCIAS DEL ESPECTÁCULO FACULTAD DE HUMANIDADES UNIVERSIDAD CARLOS III DE MADRID 2011 Tesis que, para la obtención del Título de Doctor, presenta Violetta Brázhnikova Tsýbizova bajo la dirección de la Doctora Kayoko Takagi Takanashi, Profesora Titular de Lengua y Literatura de Japón de la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid. Vº Bº La directora de la tesis doctoral ÍNDICE: INTRODUCCIÓN Recorrido El porqué de la elección del tema de la tesis Fortalecer el puente cultural entre España y Japón Criterios metodológicos y organizativos Condiciones del desarrollo del trabajo de investigación. Agradecimientos CAPÍTULO PRIMERO: CONTEXTO ESPIRITUAL DEL SURGIMIENTO DEL TEATRO KABUKI Introducción 1.1. Shintō 1.1.1. Nacimiento del Shintō 1.1.2. Mito de Amaterasu como fuente para la deificación del emperador 1.1.3. Kokugaku 1.1.4. Estructura interna del santuario shintōísta 1.1.5. Presencia femenina en el Shintō 1.1.6. Purificación 1.2. Zen como filosofía imperante en el período Edo 1.2.1. Tendencias espirituales durante el período Edo 1.2.2. Tao 1.2.2.1. Áreas de aplicación del Tao: el cuerpo y la razón 1.2.2.2. Superación del egoísmo individualista como base de la felicidad terrenal 1.2.3. Budismo 1.2.3.1.