Hokusai's Landscapes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japanese Woodblock Prints at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston Hokusai Exhibit 2015 Tokugawa Ieyasu Tokugawa Clan Rules 1615- 1850

From the Streets to the Galleries: Japanese Woodblock Prints at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston Hokusai Exhibit 2015 Tokugawa Ieyasu Tokugawa Clan Rules 1615- 1850 Kabuki theater Utamaro: Moon at Shinagawa (detail), 1788–1790 Brothel City Fashions UTAGAWA KUNIYOSHI, TAKEOUT SUSHI SUGGESTING ATAKA, ABOUT 1844 A Young Man Dallying with a Courtesan about 1680 attributed to Hishikawa Moronobu Book of Prints – Pinnacle of traditional woodblock print making Driving Rain at Shono, Station 46, from the Fifty-three Stations of the Tokkaido Road, 1833, Ando Hiroshige Actor Kawarazaki Gonjuro I as Danshichi 1860, Artist: Kunisada The In Demand Type from the series Thirty Two Physiognomic Types in the Modern World Artist: Utagawa Kunisada 1820s The Mansion of the Plates, From the Series One Hundred Ghost Stories, about 1831, Artist Katsushika Hokusai Taira no Tadanori, from the Series Warriors as Six Poetic Immortals Artist Yashima Gakutei, About 1827, Surimono Meiji Restoration. Forecast for the Year 1890, 1883, Ogata Gekko Young Ladies Looking at Japanese objects, 1869 by James Tissot La Japonaise (Camille Monet in Japanese costume) Claude Monet, 1876 The Fish, Stained glass Window, 1890, John La Farge Academics and Adventurers: Edward S. Morse, Okakura Kakuzo, Ernest Fenollosa, William Sturgis Bigelow New Age Japanese woman, About 1930s Edward Sylvester Morse Whaleback Shell Midden in Damariscotta, Maine Brachiopod Shell Brachiopod worm William Sturgis Bigelow Ernest Fenollosa Okakura Kakuzo Charles T. Spaulding https://www.mfa.org/collections /asia/tour/spaulding-collection Stepping Stones in the Afternoon, Hiratsuka Un’ichi, 1960 Azechi Umetaro, 1954 Reike Iwami, Morning Waves. 1978 Museum of Fine Arts Toulouse Lautrec and the Stars of Paris April 7-August 4 Uniqlo t-shirt. -

Nature and Culture in Visual Communication: Japanese Variations on Ludus Naturae

Semiotica 2016; aop Massimo Leone* Nature and culture in visual communication: Japanese variations on Ludus Naturae DOI 10.1515/sem-2015-0145 Abstract: The neurophysiology of vision and cognition shapes the way in which human beings visually “read” the environment. A biological instinct, probably selected as adaptive through evolution, pushes them to recognize coherent shapes in chaotic visual patterns and to impute the creation of these shapes to an anthropomorphic agency. In the west as in the east, in Italy as in Japan, human beings have identified faces, bodies, and landscapes in the bizarre chromatic, eidetic, and topologic configurations of stones, clouds, and other natural elements, as though invisible painters and sculptors had depicted the former in the latter. However, culture-specific visual ideologies immediately and deeply mold such cross-cultural instinct of pattern recognition and agency attribution. Giants and mythical monsters are seen in clouds in the west as in the east; both the Italian seventeenth-century naturalist and the Japanese seventeenth-century painter identify figures of animals and plants in stones. And yet, the ways in which they articulate the semantics of this visual recogni- tion, identify its icons, determine its agency, and categorize it in relation to an ontological framework diverge profoundly, according to such exquisitely paths of differentiation that only the study of culture, together with that of nature, can account for. Keywords: semiotics, visual communication, visual signification, pareidolia, Japanese aesthetics, agency Quapropter cum has convenientias quas dicis infidelibus quasi quasdam picturas rei gestae obtendimus, quoniam non rem gestam, sed figmentum arbitrantur esse, quod credimus quasi super nubem pingere nos existimant… (Anselm of Aosta, Cur Deus Homo,I,4) *Corresponding author: Massimo Leone, University of Turin, Department of Philosophy, Via S. -

Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J

Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei mandara Talia J. Andrei Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2016 © 2016 Talia J.Andrei All rights reserved Abstract Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J. Andrei This dissertation examines the historical and artistic circumstances behind the emergence in late medieval Japan of a short-lived genre of painting referred to as sankei mandara (pilgrimage mandalas). The paintings are large-scale topographical depictions of sacred sites and served as promotional material for temples and shrines in need of financial support to encourage pilgrimage, offering travelers worldly and spiritual benefits while inspiring them to donate liberally. Itinerant monks and nuns used the mandara in recitation performances (etoki) to lead audiences on virtual pilgrimages, decoding the pictorial clues and touting the benefits of the site shown. Addressing themselves to the newly risen commoner class following the collapse of the aristocratic order, sankei mandara depict commoners in the role of patron and pilgrim, the first instance of them being portrayed this way, alongside warriors and aristocrats as they make their way to the sites, enjoying the local delights, and worship on the sacred grounds. Together with the novel subject material, a new artistic language was created— schematic, colorful and bold. We begin by locating sankei mandara’s artistic roots and influences and then proceed to investigate the individual mandara devoted to three sacred sites: Mt. Fuji, Kiyomizudera and Ise Shrine (a sacred mountain, temple and shrine, respectively). -

Agriculture Was One of the Most Important Economic

SPATIAL DIVERSITY AND TEMPORAL CHANGE OF PLANT USE IN SAGAMI PROVINCE, CLASSICAL JAPAN: AN ARCHAEOLOGICAL APPROACH KATSUNORI TAKASE INTRODUCTION Agriculture was one of the most important economic bases of classical Japan and there were two main types of plant farming: paddy rice cultivation and dry field cultivation. There is no doubt that paddy rice cultivation was dominant in almost all of regions in classical Japan. At the same time, a lot of Japanese historians and historical geographers have disserted that farming in classical Japan was managed combining paddy rice cultivation and dry field cultivation. Classical Japanese state often recommended cultivating millets and beans beside paddy rice against a poor crop. Furthermore, in the 8th century, the state established the public relief stocking system (義倉制) for taking precautions of food shortage caused by bad weather, flood and earth quake and so on. In this system, foxtail millet was regulated to be stocked in warehouses. Therefore, agricultural policies of the state had obviously a close relationship not only with paddy rice cultivation, but also dry field farming. It is likely that combination balance ought to differ from region to region and it should reflect land use strategy of each settlement. However, there are just few written records on dry field farming in classical Japan especially before the 11th century. Even if there are fragmentary descriptions on farming, they show only kinds of grain and their crop totaled in each province or county. Therefore, it is very difficult to approach to micro-scale land use and plant use in classical Japan. Nevertheless, pictorial diagrams and wooden strips have begun to play an important role to reveal these problems. -

Powerful Warriors and Influential Clergy Interaction and Conflict Between the Kamakura Bakufu and Religious Institutions

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAllllBRARI Powerful Warriors and Influential Clergy Interaction and Conflict between the Kamakura Bakufu and Religious Institutions A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY MAY 2003 By Roy Ron Dissertation Committee: H. Paul Varley, Chairperson George J. Tanabe, Jr. Edward Davis Sharon A. Minichiello Robert Huey ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Writing a doctoral dissertation is quite an endeavor. What makes this endeavor possible is advice and support we get from teachers, friends, and family. The five members of my doctoral committee deserve many thanks for their patience and support. Special thanks go to Professor George Tanabe for stimulating discussions on Kamakura Buddhism, and at times, on human nature. But as every doctoral candidate knows, it is the doctoral advisor who is most influential. In that respect, I was truly fortunate to have Professor Paul Varley as my advisor. His sharp scholarly criticism was wonderfully balanced by his kindness and continuous support. I can only wish others have such an advisor. Professors Fred Notehelfer and Will Bodiford at UCLA, and Jeffrey Mass at Stanford, greatly influenced my development as a scholar. Professor Mass, who first introduced me to the complex world of medieval documents and Kamakura institutions, continued to encourage me until shortly before his untimely death. I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to them. In Japan, I would like to extend my appreciation and gratitude to Professors Imai Masaharu and Hayashi Yuzuru for their time, patience, and most valuable guidance. -

Meisho Zue and the Mapping of Prosperity in Late Tokugawa Japan

Meisho Zue and the Mapping of Prosperity in Late Tokugawa Japan Robert Goree, Wellesley College Abstract The cartographic history of Japan is remarkable for the sophistication, variety, and ingenuity of its maps. It is also remarkable for its many modes of spatial representation, which might not immediately seem cartographic but could very well be thought of as such. To understand the alterity of these cartographic modes and write Japanese map history for what it is, rather than what it is not, scholars need to be equipped with capacious definitions of maps not limited by modern Eurocentric expectations. This article explores such classificatory flexibility through an analysis of the mapping function of meisho zue, popular multivolume geographic encyclopedias published in Japan during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The article’s central contention is that the illustrations in meisho zue function as pictorial maps, both as individual compositions and in the aggregate. The main example offered is Miyako meisho zue (1780), which is shown to function like a map on account of its instrumental pictorial representation of landscape, virtual wayfinding capacity, spatial layout as a book, and biased selection of sites that contribute to a vision of prosperity. This last claim about site selection exposes the depiction of meisho as a means by which the editors of meisho zue recorded a version of cultural geography that normalized this vision of prosperity. Keywords: Japan, cartography, Akisato Ritō, meisho zue, illustrated book, map, prosperity Entertaining exhibitions arrayed on the dry bed of the Kamo River distracted throngs of people seeking relief from the summer heat in Tokugawa-era Kyoto.1 By the time Osaka-based ukiyo-e artist Takehara Shunchōsai (fl. -

Schaftliches Klima Und Die Alte Frau Als Feindbild

6 Zusammenfassung und Schluss: Populärkultur, gesell- schaftliches Klima und die alte Frau als Feindbild Wie ein extensiver Streifzug durch die großstädtische Populärkultur der späten Edo-Zeit gezeigt hat, tritt darin etwa im letzten Drittel der Edo-Zeit der Typus hässlicher alter Weiber mit zahlreichen bösen, ne- gativen Eigenschaften in augenfälliger Weise in Erscheinung. Unter Po- pulärkultur ist dabei die Dreiheit gemeint, die aus dem volkstümlichen Theater Kabuki besteht, den polychromen Holzschnitten, und der leich- ten Lektüre der illustrierten Romanheftchen (gōkan) und der – etwas gehobenere Ansprüche bedienenden – Lesebücher (yomihon), die mit einem beschränkten Satz von Schriftzeichen auskamen und der Unter- haltung und Erbauung vornehmlich jener Teile der Bevölkerung dien- ten, die nur eine einfache Bildung genossen hatten. Durch umherziehen- de Leihbuchhändler fand diese Art der Literatur auch über den groß- städtischen Raum hinaus bis hin in die kleineren Landflecken und Dör- fer hinein Verbreitung. Die drei Medien sind vielfach verschränkt: Holzschnitte dienen als Werbemittel für bzw. als Erinnerungsstücke an Theateraufführungen; Theaterprogramme sind reich illustrierte kleine Holzschnittbücher; die Stoffe der Theaterstücke werden in den zahllo- sen Groschenheften in endlosen Varianten recyclet; in der Heftchenlite- ratur spielt die Illustration eine maßgebliche Rolle, die Illustratoren sind dieselben wie die Zeichner der Vorlagen für die Holzschnitte; in einigen Fällen sind Illustratoren und Autoren identisch; Autoren steuern Kurz- texte als Legenden für Holzschnitte bei. Nachdrücklich muss der kommerzielle Aspekt dieser „Volkskultur“ betont werden. In allen genannten Sparten dominieren Auftragswerke, die oft in nur wenigen Tagen erledigt werden mussten. Die Theaterbe- treiber ließen neue Stücke schreiben oder alte umschreiben beziehungs- weise brachten Kombinationen von Stücken zur Aufführung, von wel- chen sie sich besonders viel Erfolg versprachen. -

Vegetable Production and the Diet in Rural Villages by Ayako Ehara (Professor Emeritus, Tokyo Kasei-Gakuin University)

Vegetables and the Diet of the Edo Period, Part 2 Vegetable Production and the Diet in Rural Villages By Ayako Ehara (Professor Emeritus, Tokyo Kasei-Gakuin University) Introduction compiled by Tomita Iyahiko and completed in 1873, describes the geography and culture of Hida During the Edo period (1603–1868), the number of province. It contains records from 415 villages in villages in Japan remained fairly constant with three Hida counties, including information on land roughly 63,200 villages in 1697 and 63,500 140 years value, number of households, population and prod- later in 1834. According to one source, the land ucts, which give us an idea of the lifestyle of these value of an average 18th and 19th century village, with villagers at the end of the Edo period. The first print- a population of around 400, was as much as 400 to ed edition of Hidago Fudoki was published in 1930 500 koku1, though the scale and character of each vil- (by Yuzankaku, Inc.), and was based primarily on the lage varied with some showing marked individuality. twenty-volume manuscript held by the National In one book, the author raised objections to the gen- Archives of Japan. This edition exhibits some minor eral belief that farmers accounted for nearly eighty discrepancies from the manuscript, but is generally percent of the Japanese population before and during identical. This article refers primarily to the printed the Edo period. Taking this into consideration, a gen- edition, with the manuscript used as supplementary eral or brief discussion of the diet in rural mountain reference. -

Katsushika Hokusai Born in 1760 and Died in 1849 in Edo, Japan

1 Excerpted from Kathleen Krull, Lives of the Artists, 1995, 32 – 35. OLD MAN MAD ABOUT DRAWING KATSUSHIKA HOKUSAI BORN IN 1760 AND DIED IN 1849 IN EDO, JAPAN Japanese painter and printmaker, known for his enormous influence on both Eastern and Western art THE MAN HISTORY knows as Katsushika Hokusai was born in the Year of the Dragon in the bustling city now known as Tokyo. After working for eight stormy years in the studio of a popular artist who resented the boy's greater skill, Hokusai was finally thrown out. At first he earned his daily bowl of rice as a street peddler, selling red peppers and ducking if he saw his old teacher coming. Soon he was illustrating comic books, then turning out banners, made-to-order greeting cards for the rich, artwork for novels full of murders and ghosts, and drawings of scenes throughout his beloved Edo. Changing one's name was a Japanese custom, but Hokusai carried it to an extreme—he changed his more than thirty times. No one knows why. Perhaps he craved variety, or was self-centered (thinking that every change in his art style required a new identity), or merely liked being eccentric. One name he kept longer than most was Hokusai, meaning "Star of the Northern Constellation," in honor of a Buddhist god he especially revered. He did like variety in dwellings. Notorious for never cleaning his studio, he took the easy way out whenever the place became too disgustingly dirty: he moved. Hokusai moved a total of ninety-three times—putting a burden on his family and creating a new set of neighbors for himself at least once a year. -

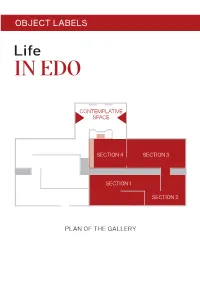

Object Labels

OBJECT LABELS CONTEMPLATIVE SPACE SECTION 4 SECTION 3 SECTION 1 SECTION 2 PLAN OF THE GALLERY SECTION 1 Travel Utagawa Hiroshige Procession of children passing Mount Fuji 1830s Hiroshige playfully imitates with children a procession of a daimyo passing Mt Fuji. A popular subject for artists, a daimyo and his entourage could make for a lively scene. During Edo, daimyo were required to travel to Edo City every other year and live there under the alternate attendance (sankin- kōtai) system. Hundreds of retainers would transport weapons, ceremonial items, and personal effects that signal the daimyo’s military and financial might. Some would be mounted on horses; the daimyo and members of his family carried in palanquins. Cat. 5 Tōshūsai Sharaku Actor Arashi Ryūzō II as the Moneylender Ishibe Kinkichi 1794 Kabuki actor portraits were one of the most popular types of ukiyo-e prints. Audiences flocked to see their favourite kabuki performers, and avidly collected images of them. Actors were stars, celebrities much like the idols of today. Sharaku was able to brilliantly capture an actor’s performance in his expressive portrayals. This image illustrates a scene from a kabuki play about a moneylender enforcing payment of a debt owed by a sick and impoverished ronin and his wife. The couple give their daughter over to him, into a life of prostitution. Playing a repulsive figure, the actor Ryūzō II made the moneylender more complex: hard-hearted, gesturing like a bully – but his eyes reveal his lack of confidence. The character is meant to be disliked by the audience, but also somewhat comical. -

2021 Olympic Guidebook

TOKYO SUMMER GAMES GUIDEBOOK PRESENTED BY VINE CONNECTIONS 2 Konnichiwa, The summer games in Tokyo are around the corner and it is the Summer of Sake! I’ve created this guide that features more about the Summer Games in Tokyo, when to watch, what’s new about the games, interesting culture and travel tips around Japan, how to enjoy Japanese sake and spirits, cocktail recipes, and more. At Vine Connections, we’ve been importing premium Japanese sake for over 19 years and currently represent 41 different sakes across 13 prefectures in Japan. Our breweries are steeped in centuries-old tradition, and our portfolio spans traditional style sakes to umami-driven to crisp daiginjos to the funky unexpected. Our sakes are intriguing, connective, provocative, magnetic, and innovative. We have the most comprehensive and diverse sake portfolio. Japanese culture and interest has never been more relevant. The Japanese restaurant industry in the US is projected to grow +25% in 2021, with $27.5 billion in restaurant sales. Consumer demand for Japanese sake is booming with a growth of 36% in retail, up +75% in grocery in 2020. So dive in with me, and let me know how I can be a resource for samples, article ideas, consumer insights and travel tips for future trips. Thank you, Monica Samuels Vine Connections Vice President of Sake & Spirits [email protected] | 562.331.0128 3 TOKYO SUMMER GAMES EVENTS SCHEDULE OPENING CEREMONY - JULY 23 Cycling Mountain Bike - July 26-27 Baseball/Softball - July 21-August 7 Canoe Slalom - July 25-30 Football - July -

Art Spotlight: Hokusai's Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fiji

Art Spotlight: Hokusai's Thirty-six Views of Mount Fiji This document has all 36 prints from Hokusai's Thirty-six Views of Mount Fiji. The following links will help you discuss these works with your children. • Art Spotlight: Hokusai's Thirty-six Views of Mount Fiji: The original blog post about these works with commentary, discussion questions, and learning activities • Woodblock Printing with Kids tutorial • Free Art Appreciation Printable Worksheet Bundle • How to Look at Art with Children • All art posts on the Art Curator for Kids The Art Curator for Kids, Cindy Zerm Ingram, [email protected], http://artcuratorforkids.com/ Conventions of Japanese Ukiyo-e Prints • peaceful, harmonious scenes • asymmetrical composition • limited color palette of about 4 colors plus black • unclear space or perspective • diagonal or curved lines that guide your eye through the composition • outlined shapes filled with solid, flat color The Art Curator for Kids, Cindy Zerm Ingram, [email protected], http://artcuratorforkids.com/ The Art Curator for Kids, Cindy Zerm Ingram, [email protected], http://artcuratorforkids.com/ Questions to Ask • What is going on in this artwork? What do you see that makes you say that? • What emotions do you feel when looking at this artwork? What emotions do you think the artist was feeling? • Describe the lines and colors in this artwork. How do the colors and lines contribute to the emotion? • Describe the ways Hokusai included Mount Fuji in the artworks. • What can you tell about the Japanese way of life in the Edo Period by looking at these artworks? What types of things are the people doing? • What do these artworks have in common? How could you tell that these were created by Hokusai during this time period? The Art Curator for Kids, Cindy Zerm Ingram, [email protected], http://artcuratorforkids.com/ The Art Curator for Kids, Cindy Zerm Ingram, [email protected], http://artcuratorforkids.com/ Learning Activities 1.