Redalyc.Ukiyo-E in the Gulbenkian Collection. a Few Examples

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Timely Timeless.Indd 1 2/12/19 10:26 PM Published by the Trout Gallery, the Art Museum of Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania 17013

Timely and Timeless Timely Timely and Timeless Japan’s Modern Transformation in Woodblock Prints THE TROUT GALLERY G38636_SR EXH ArtH407_TimelyTimelessCover.indd 1 2/18/19 2:32 PM March 1–April 13, 2019 Fiona Clarke Isabel Figueroa Mary Emma Heald Chelsea Parke Kramer Lilly Middleton Cece Witherspoon Adrian Zhang Carlisle, Pennsylvania G38636_SR EXH ArtH407_Timely Timeless.indd 1 2/12/19 10:26 PM Published by The Trout Gallery, The Art Museum of Dickinson College, Carlisle, Pennsylvania 17013 Copyright © 2019 The Trout Gallery. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from The Trout Gallery. This publication was produced in part through the generous support of the Helen Trout Memorial Fund and the Ruth Trout Endowment at Dickinson College. First Published 2019 by The Trout Gallery, Carlisle, Pennsylvania www.trougallery.org Editor-in-Chief: Phillip Earenfight Design: Neil Mills, Design Services, Dickinson College Photography: Andrew Bale, unless otherwise noted Printing: Brilliant Printing, Exton, Pennsylvania Typography: (Title Block) D-DIN Condensed, Brandon Text, (Interior) Adobe Garamond Pro ISBN: 978-0-9861263-8-3 Printed in the United States COVER: Utagawa Hiroshige, Night View of Saruwaka-machi, from the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (detail), 1856. Woodblock print, ink and color on paper. The Trout Gallery, Dickinson College, Carlisle, PA. 2018.3.14 (cat. 7). BACK COVER: Utagawa Hiroshige, Night View of Saruwaka-machi, from the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (detail), 1856. -

Publisbing Culture in Eighteentb-Century Japan: the Case of the Edo Publisher Tsutaya Jqzaburô (1751-97)

Publisbing Culture in Eighteentb-Century Japan: The Case of the Edo Publisher Tsutaya JQzaburô (1751-97) Yu Chang A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto 0 Copyright by Yu Chang 1997 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1*1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliogtaphic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellingtm Ottawa ON K1A ON4 OnawaOFJ KlAW Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence diowing the exclusive permettant à la National Librq of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seil reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othenvise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author' s ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT Publishing Culture in Eighteentb-Century Japan: The Case of the Edo Pubüsher Tsutaya Jûzaburô (1750-97) Master of Arts, March 1997 Yu Chang Department of East Asian Studies During the ideologicai program of the Senior Councillor Mitsudaira Sadanobu of the Tokugawa bah@[ governrnent, Tsutaya JÛzaburÔ's aggressive publishing venture found itseif on a collision course with Sadanobu's book censorship policy. -

Ukiyo-E DAIGINJO

EXCLUSIVE JAPANESE IMPORT Ukiyo-e DAIGINJO UKIYO-E BREWERY Ukiyo-e (ooh-kee-yoh-eh) is a Japanese Founded in 1743 in the Nada district of woodblock print or painting of famous Kobe, Hakutsuru is the #1 selling sake kabuki actors, beautiful women, travel brand in Japan. landscapes and city life from the Elegant, thoughtful, and delicious Edo period. Ukiyo-e is significant in sake defines Hakutsuru, but tireless expressing the sensual attributes of innovation places it in a class of its Japanese culture from 17th to 19th own. Whether it’s understanding water century. sources at the molecular level, building a facility to create one-of-a-kind yeast, ARTIST/CHARACTER or developing its own sake-specific rice, Hakutsuru Nishiki, it’s the deep dive into This woodblock print displays the famed research and development that explains kabuki actor, Otani Oniji III, as Yakko Hakutsuru’s ascension to the top of a Edobei in the play, Koi Nyobo Somewake centuries-old craft. Tazuna. The play was performed at the Kawarazakiza theater in May 1794. The artist, Toshusai Sharaku, was known for Brewery Location Hyogo Prefecture creating visually bold prints that gave a Founding Date 1743 Brewmaster Mitsuhiro Kosa revealing look into the world of kabuki. DAIGINJO DAIGINJO DEFINED Just like Ukiyo-e, making beautiful sake Sake made with rice milled to at least takes time, mastery, and creativity. To 50% of its original size, water, koji, and a craft an exquisite sake, such as this small amount of brewers’ alcohol added aromatic and enticing Daiginjo, is both for stylistic purposes. -

Schaftliches Klima Und Die Alte Frau Als Feindbild

6 Zusammenfassung und Schluss: Populärkultur, gesell- schaftliches Klima und die alte Frau als Feindbild Wie ein extensiver Streifzug durch die großstädtische Populärkultur der späten Edo-Zeit gezeigt hat, tritt darin etwa im letzten Drittel der Edo-Zeit der Typus hässlicher alter Weiber mit zahlreichen bösen, ne- gativen Eigenschaften in augenfälliger Weise in Erscheinung. Unter Po- pulärkultur ist dabei die Dreiheit gemeint, die aus dem volkstümlichen Theater Kabuki besteht, den polychromen Holzschnitten, und der leich- ten Lektüre der illustrierten Romanheftchen (gōkan) und der – etwas gehobenere Ansprüche bedienenden – Lesebücher (yomihon), die mit einem beschränkten Satz von Schriftzeichen auskamen und der Unter- haltung und Erbauung vornehmlich jener Teile der Bevölkerung dien- ten, die nur eine einfache Bildung genossen hatten. Durch umherziehen- de Leihbuchhändler fand diese Art der Literatur auch über den groß- städtischen Raum hinaus bis hin in die kleineren Landflecken und Dör- fer hinein Verbreitung. Die drei Medien sind vielfach verschränkt: Holzschnitte dienen als Werbemittel für bzw. als Erinnerungsstücke an Theateraufführungen; Theaterprogramme sind reich illustrierte kleine Holzschnittbücher; die Stoffe der Theaterstücke werden in den zahllo- sen Groschenheften in endlosen Varianten recyclet; in der Heftchenlite- ratur spielt die Illustration eine maßgebliche Rolle, die Illustratoren sind dieselben wie die Zeichner der Vorlagen für die Holzschnitte; in einigen Fällen sind Illustratoren und Autoren identisch; Autoren steuern Kurz- texte als Legenden für Holzschnitte bei. Nachdrücklich muss der kommerzielle Aspekt dieser „Volkskultur“ betont werden. In allen genannten Sparten dominieren Auftragswerke, die oft in nur wenigen Tagen erledigt werden mussten. Die Theaterbe- treiber ließen neue Stücke schreiben oder alte umschreiben beziehungs- weise brachten Kombinationen von Stücken zur Aufführung, von wel- chen sie sich besonders viel Erfolg versprachen. -

Utagawa Hiroshige

Utagawa Hiroshige Contemporary Landscapes Utagawa Hiroshige (Japanese: 歌川 広重), also Andō Hiroshige (Japanese: 安藤 広重; 1797 – 12 October 1858) was a Japanese ukiyo-e artist, considered the last great master of that tradition. Hiroshige is best known for his landscapes, such as the series The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō and The Sixty-nine Stations of the Kiso Kaidō; and for his depictions of birds and flowers. The subjects of his work were atypical of the ukiyo-e genre, whose typical focus was on beautiful women, popular actors, and other scenes of the urban pleasure districts of Japan's Edo period (1603–1868). The popular Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji series by Hokusai was a strong influence on Hiroshige's choice of subject, though Hiroshige's approach was more poetic and ambient than Hokusai's bolder, more formal prints. For scholars and collectors, Hiroshige's death marked the beginning of a rapid decline in the ukiyo-e genre, especially in the face of the westernization that followed the Meiji Restoration of 1868. Hiroshige's work came to have a marked influence on Western painting towards the close of the 19th century as a part of the trend in Japonism. Western artists closely studied Hiroshige's compositions, and some, such as van Gogh, painted copies of Hiroshige's prints. Hiroshige was born in 1797 in the Yayosu Quay section of the Yaesu area in Edo (modern Tokyo).[1] He was of a samurai background,[1] and was the great-grandson of Tanaka Tokuemon, who held a position of power under the Tsugaru clan in the northern province of Mutsu. -

Extreme Japan

Extreme Japan At its roots, Japan has two deities who represent opposite extremes – Amaterasu, a Nigitama (peaceful spirit), and Susanoo, an Aratama (wrathful spirit). The dichotomy can be seen reflected in various areas of the culture. There is Kinkaku-ji (the Golden Pavilion) to represent the Kitayama culture, and Ginkaku-ji (the Silver Pavilion) to represent the Higashiyama culture. Kabuki has its wagoto (gentle style) and aragoto (bravura style). There are the thatched huts of wabicha (frugal tea ceremony) as opposed to the golden tea ceremony houses. Japan can be punk – flashy and noisy. Or, it can be bluesy – deep and tranquil. Add to flash, the kabuki way. Subtract to refine, the wabi way. Just don’t hold back - go to the extreme.Either way, it’s Japan. Japan Concept 5 Kabuku Japan Concept 6 wabi If we awaken and recapture the basic human passions that are today being lost in each moment, new Japanese traditions will be passed on with a bold, triumphant face. Taro Okamoto, Nihon no Dento (Japanese Tradition) 20 kabuku Extreme Japan ① Photograph: Satoshi Takase ③ ② Eccentrics at the Cutting Edge of Fashion ① Lavish preferences of truck drivers are reflected in vehicles decorated like illuminated floats. ② The crazy KAWAII of Kyary Pamyu Pamyu. ③ The band KISHIDAN. Yankii style, characterized by tsuppari hairstyles and customized high ⑤ school uniforms. ④ Kabuki-style cosmetic face masks made by Imabari Towel. Kabuki’s Kumadori is a powerful makeup for warding off evil spirits. ⑤ Making lavish use of combs and hairpins, oiran were the fashion leaders of Edo. The “face-showing” event is a glimpse into the sleepless world of night. -

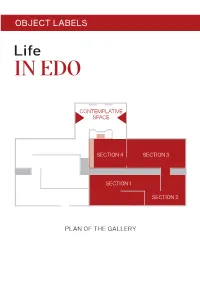

Object Labels

OBJECT LABELS CONTEMPLATIVE SPACE SECTION 4 SECTION 3 SECTION 1 SECTION 2 PLAN OF THE GALLERY SECTION 1 Travel Utagawa Hiroshige Procession of children passing Mount Fuji 1830s Hiroshige playfully imitates with children a procession of a daimyo passing Mt Fuji. A popular subject for artists, a daimyo and his entourage could make for a lively scene. During Edo, daimyo were required to travel to Edo City every other year and live there under the alternate attendance (sankin- kōtai) system. Hundreds of retainers would transport weapons, ceremonial items, and personal effects that signal the daimyo’s military and financial might. Some would be mounted on horses; the daimyo and members of his family carried in palanquins. Cat. 5 Tōshūsai Sharaku Actor Arashi Ryūzō II as the Moneylender Ishibe Kinkichi 1794 Kabuki actor portraits were one of the most popular types of ukiyo-e prints. Audiences flocked to see their favourite kabuki performers, and avidly collected images of them. Actors were stars, celebrities much like the idols of today. Sharaku was able to brilliantly capture an actor’s performance in his expressive portrayals. This image illustrates a scene from a kabuki play about a moneylender enforcing payment of a debt owed by a sick and impoverished ronin and his wife. The couple give their daughter over to him, into a life of prostitution. Playing a repulsive figure, the actor Ryūzō II made the moneylender more complex: hard-hearted, gesturing like a bully – but his eyes reveal his lack of confidence. The character is meant to be disliked by the audience, but also somewhat comical. -

2019/10/30 Edo-Tokyo Museum News 15

English Edition15 Oct. 25 Fri. 2019 No.15 Special Exhibition Saturday, September 14, to Monday, November 4 — Peacekeeping Contributors Special Exhibition Gallery, 1F Samurai in Edo Period *Displays will be changed during the exhibition. A matchlock that could be used on horseback. Horseback matchlock, bullet cases, bullets and priming powder that belonged to NONOMURA Ichinoshin End of Edo period Information Hours: 9:30 – 17:30 (until 19:30 on Saturdays). Last admission 30 minutes before closing. Closed: Mondays (except for September 23, October 14, and November 4), Tuesday, September 24, and Tuesday, October 15. Look at these Organaization: Tokyo Metropolitan Foundation for History and Culture Tokyo Metropolitan Edo-Tokyo Museum, dignied fellows The Asahi Shimbun. — these are samurai ! Admission: ‘Ofcials Belonging to Admission Fee (tax included) Special exhibition only Special and permanent exhibition the Satsuma Domain’ Standard adult ¥1,100 (¥880) ¥1,360 (¥1,090) University/college students ¥880 (¥700) ¥1,090 (¥870) Photographer: Felice Beato c. 1863–1870 Middle and high school students. Seniors 65+ ¥550 (¥440) ¥680 (¥550) Private collection Tokyo middle school students and elementary school students ¥550 (¥440) None Notes: • Fees in parentheses are for groups of twenty or more. “Samurai” is a key word used oen to dene the image of Japan, both at home and abroad. at • Fees are waived in the following cases: Children below school age and individuals with a Shintai Shogaisha Techo (Physical Disability Certicate), Ai-no-Techo (Intellectual Disability Certicate), Ryoiku Techo (Rehabilitation Certicate), Seishin Shogaisha Hoken Fukushi Techo words associations, however, vary from person to person. A member of the samurai class, a (Certicate for Health and Welfare of People with Mental Disorders), or Hibakusha Kenko Techo (Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certicate) and up to two people accompanying them. -

Eight Views of the Xiao and Xiang

1 College of Arts at the University of Canterbury Art History and Theory in the School of Humanities ARTH 690 Masters Thesis Title of Thesis: The Eight Views: from its origin in the Xiao and Xiang rivers to Hiroshige. Jennifer Baker Senior Supervisor: Dr. Richard Bullen (University of Canterbury). Co-Supervisor: Dr. Rachel Payne (University of Canterbury). Thesis Start Registration Date: 01 March 2009. Thesis Completion Date: 28 February 2010. Word Count: 30, 889. 2 Abstract This thesis focuses upon the artistic and poetic subject of the Eight Views of the Xiao and Xiang, from its origin in the Xiao-Xiang region in the Hunan province of China throughout its dispersal in East Asian countries such as Korea and Japan. Certain aesthetics and iconography were retained from the early examples, throughout the Eight Views’ transformation from the eleventh to the nineteenth century. The subject‟s close associations with poetry, atmospheric phenomena and the context of exile were reflected in the imagery of the painting and the accompanying verses. This thesis will discuss the historic, geographic and poetic origins of the Eight Views, along with a thorough investigation into the artistic styles which various East Asian artists employed in their own interpretations of the series. Furthermore, the dispersal and diaspora of the subject throughout East Asia are also investigated in this thesis. The work of Japanese artist Andô Hiroshige will serve as the concluding apogee. The Eight Views of the Xiao and Xiang is an important East Asian artistic subject in both poetry and painting and contains many pervasive East Asian aesthetics. -

Hokusai's Landscapes

$45.00 / £35.00 Thomp HOKUSAI’S LANDSCAPES S on HOKUSAI’S HOKUSAI’S sarah E. thompson is Curator, Japanese Art, HOKUSAI’S LANDSCAPES at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. The CompleTe SerieS Designed by Susan Marsh SARAH E. THOMPSON The best known of all Japanese artists, Katsushika Hokusai was active as a painter, book illustrator, and print designer throughout his ninety-year lifespan. Yet his most famous works of all — the color woodblock landscape prints issued in series, beginning with Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji — were produced within a relatively short time, LANDSCAPES in an amazing burst of creative energy from about 1830 to 1836. These ingenious designs, combining MFA Publications influences from several different schools of Asian Museum of Fine Arts, Boston art as well as European sources, display the 465 Huntington Avenue artist’s acute powers of observation and trademark Boston, Massachusetts 02115 humor, often showing ordinary people from all www.mfa.org/publications walks of life going about their business in the foreground of famous scenic vistas. Distributed in the United States of America and Canada by ARTBOOK | D.A.P. Hokusai’s landscapes not only revolutionized www.artbook.com Japanese printmaking but also, within a few decades of his death, became icons of art Distributed outside the United States of America internationally. Illustrated with dazzling color and Canada by Thames & Hudson, Ltd. reproductions of works from the largest collection www.thamesandhudson.com of Japanese prints outside Japan, this book examines the magnetic appeal of Hokusai’s Front: Amida Falls in the Far Reaches of the landscape designs and the circumstances of their Kiso Road (detail, no. -

Download ARTHIST432S Weisenfeld Semester Outline

WEEK DATE TOPIC/ASSIGNMENT 1 Jan 20 (W) Introduction: Course Overview 2 Jan 25 What is Ukiyo-e (Pictures of the Floating World)? Jenkins, Donald. “Introduction,” in Donald Jenkins, ed., The Floating World Revisited. Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press and Portland Art Museum, 1993: 3-23. Hokusai: The Suspended Threat (Section 3 (8:50-14:30) How to Make a Woodblock Print) [electronic resource], Films Media Group, 1999. Online Video available through Duke library catalogue (Search “Films on Demand”). Specialized printing techniques: http://pulverer.si.edu/node/189 Davis, Julie Nelson. “Picturing the Floating World: Ukiyo-e in Context” (Talk 50 minutes – Q&A after optional) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UQXfb6JOby0 Jan 27 Collaboration and the Ukiyo-e Quartet *Visitor: Professor Julie Nelson Davis (University of Pennsylvania) 3 Feb 1 Bordello Chic and Edo Eroticism Discussion Leaders: Seigle, Cecelia. Yoshiwara: The Glittering World of the Japanese Courtesan. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press: 1-13. Screech, Timon. “Introduction” and “Chapter 1: Erotic Images, Pornography, Shunga and Their Use,” in Sex and the Floating World, Reaktion Press, 2009: 7-38. The British Museum Shunga Exhibition: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=T9eNggxOu-o&t=21 Utamaro and his Five Women, dir. Kenji Mizoguchi Feb 3 Bordello Chic and Edo Eroticism continued 4 Feb 8 The Realms of Spectacle: Kabuki and Sumo Discussion Leaders: Clark, Timothy. “Edo Kabuki in the 1780s,” in The Actor’s Image: Printmakers of the Katsukawa School. The Art Institute of Chicago, 1994: 27-48. Kominz, Laurence. “Ichikawa Danjurō V and Kabuki’s Golden Age,” in The Floating World Revisited: 63-83. -

Spectacular Three Day Fall Auction - Fine Antiques, Antiquities and Asian Treasures - Day Three Monday 05 November 2012 11:00

Spectacular Three Day Fall Auction - Fine Antiques, Antiquities and Asian Treasures - Day Three Monday 05 November 2012 11:00 Thomaston Place Auction Galleries (USA) 51 Atlantic Highway Thomaston Maine 04861 Thomaston Place Auction Galleries (USA) (Spectacular Three Day Fall Auction - Fine Antiques, Antiquities and Asian Treasures - Day Three) Catalogue - Downloaded from UKAuctioneers.com Lot: 1300 Lot: 1306 SET (4) HANDCOLORED ENGRAVINGS - 'Four Prints of an CHARCOAL DRAWING BY HYMAN BLOOM-Hyman Bloom (. Election' by William Hogarth (British, 1697-1764), engraved by 1913- 2009), considered by Jackson Pollack to be the first Charles Grignion (1717-1810), signed in plate, including the Abstract Expressionist painter. Landscape #24, charcoal and plates: 'An Election Entertainment', 'Canvassing for Votes', 'The white chalk on paper, In a welded aluminum gallery frame, 69"x Polling' and 'Chairing the Members', Paulson #198-201; these 46" Good condition, unexamined out of frame. From the Marvin are the 1822 Heath edition on wove paper, unframed, Sadik Collection. Estimates are In US Dollars : $2000-2500 shrinkwrapped, 17 1/2" x 22" impression, 19 1/4" x 24 3/4" sheet, edge chips and bends, light handling dimples. Estimates are In US Dollars : $2400-3200 Lot: 1307 MEZZOTINT ENGRAVING AFTER GEORGE STUBBS, "LION AND STAG" Stubbs( 1724 -1806) was an English artist, best Lot: 1301 known for his paintings of horses. Mezzotint engraving, SS: 18 MONUMENTAL WOODBLOCK PRINT - Self-Portrait by 1/2" x 22" , OS: 22" x 25 1/2", Restorations and minor Leonard Baskin (MA/NY, 1922-2000), Artist's Proof, just his abrasions. From the Marvin Sadik Collection. Estimates are In head rendered in green and black, captioned below in the print US Dollars : $1800-2000 'LB-AET-S-51', pencil signed and inscribed 'To Marvin with Leonard's Abiding and Constant Regards', unframed, 31 1/2" x 23 1/4" on 35" x 23 3/4" sheet of Japan paper, corner and edge Lot: 1308 bends, image is fine.