Pigments in Later Japanese Paintings : Studies Using Scientific Methods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leprosy and Other Skin Disorders

Copyright by Robert Joseph Gallagher 2014 The report committee for Robert Joseph Gallagher Certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: An Annotated Translation of Chapter 7 of the Carakasaṃhitā Cikitsāsthāna: Leprosy and Other Skin Disorders APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: __________________________________ Donald R. Davis _________________________________ Joel Brereton An Annotated Translation of Chapter 7 of the Carakasaṃhitā Cikitsāsthāna: Leprosy and Other Skin Disorders by Robert Joseph Gallagher, B.A., M.A. Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment for the degree of Master of Arts University of Texas at Austin May 2014 Dedication To my wife Virginia and our two daughters Michelle and Amy, who showed patience and understanding during my long hours of absence from their lives, while I worked on mastering the intricacies of the complex but very rewarding language of Sanskrit. In addition, extra kudos are in order for thirteen year-old Michelle for her technical support in preparing this report. Acknowledgements I wish to thank all the members of the South Asia team at UT Austin, including Prof. Joel Brereton, Merry Burlingham, Prof. Don Davis, Prof. Oliver Freiberger, Prof. Edeltraud Harzer, Prof. Patrick Olivelle, Mary Rader, Prof. Martha Selby and Jennifer Tipton. Each one has helped me along this path to completion of the M.A. degree. At the time of my last serious academic research, I used a typewriter to put my thoughts on paper. The transition from white-out to pdf has been challenging for me at times, and I appreciate all the help given to me by the members of the South Asia team. -

74 Oil Seeds and Oleaginous Fruits, Miscellaneous Grains, Seeds and Fruit

SECTION II 74 CHAPTER 12 CHAPTER 12 Oil seeds and oleaginous fruits, miscellaneous grains, seeds and fruit; industrial or medicinal plants; straw and fodder NOTES 1. Heading 1207 applies, inter alia, to palm nuts and kernels, cotton seeds, castor oil seeds, sesamum seeds, mustard seeds, safflower seeds, poppy seeds and shea nuts (karite nuts). It does not apply to products of heading 0801 or 0802 or to olives (Chapter 7 or Chapter 20). 2. Heading 1208 applies not only to non-defatted flours and meals but also to flours and meals which have been partially defatted or defatted and wholly or partially refatted with their original oils. It does not, however, apply to residues of headings 2304 to 2306. 3. For the purposes of heading 1209, beet seeds, grass and other herbage seeds, seeds of ornamental flowers, vegetable seeds, seeds of forest trees, seeds of fruit trees, seeds of vetches (other than those of the species Vicia faba) or of lupines are to be regarded as “seeds of a kind used for sowing”. Heading 1209 does not, however, apply to the following even if for sowing : (a) leguminous vegetables or sweet corn (Chapter 7); (b) spices or other products of Chapter 9; (c) cereals (Chapter 10); or (d) products of headings 1201 to 1207 or heading 1211. 4. Heading 1211 applies, inter alia, to the following plants or parts thereof: basil, borage, ginseng, hyssop, liquorice, all species of mint, rosemary, rue, sage and wormwood. Heading 1211 does not, however, apply to : (a) medicaments of Chapter 30; (b) perfumery, cosmetic or toilet preparations of Chapter 33; or (c) insecticides, fungicides, herbicides, disinfectants or similar products of heading 3808. -

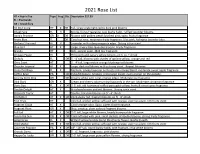

2021 Rose List HT = Hybrid Tea Type Frag Dis

2021 Rose List HT = Hybrid Tea Type Frag Dis. Description $27.99 FL = Floribunda GR = Grandiflora All My Loving HT X DR Tall, large single light red to dark pink blooms Angel Face FL X Strong, Citrus Fragrance. Low bushy habit, ruffled lavander blooms. Anna's Promise GR X DR Blooms with golden petals blushed pink; spicy, fruity fragrance Arctic Blue FL DR Good cut rose, moderate fruity fragrance. Lilac pink, fading to lavander blue. Barbara Streisand HT X Lavender with a deep magenta edge. Strong citrus scent. Blue Girl HT X Large, silvery liliac-lavender blooms. Fruity fragrance. Brandy HT Rich, apricot color. Mild tea fragrance. Chicago Peace HT Phlox pink and canary yellow blooms on 6' to 7' shrub Chihuly FL DR 3' - 4' tall, blooms with shades of apricot yellow, orange and red Chris Evert HT 3' - 4' tall, large melon orange blushing red blooms Chrysler Imperial HT X Large, dark red blooms with a strong scent. Repeat bloomer Cinco De Mayo FL X Medium, smoky lavender and rusty red-orange blend, moderate sweet apple fragrance Coffee Bean PA DR Patio/Miniature. Smokey, red-orange inside, rusty orange on the outside. Coretta Scott King GR DR Creamy white with coral, orange edges. Moderate tea fragrance. Dick Clark GR X Cream and cherry color turning burgundy in the sun. Moderate cinnamon fragrance. Doris Day FL X DR 3'-5' tall, old-fashioned ruffled pure gold yellow, fruity & sweet spice fragrance Double Delight HT X Bi-colored cream and red blooms. Strong spice scent. Elizabeth Taylor HT Double, hot-pink blooms on 5' - 6' shrub Firefighter HT X DR Deep dusky red, fragrant blooms on 5' - 6' shrub First Prize HT Very tall, golden yellow suffused with orange, vigorous plant, rich fruity scent Fragrant Cloud HT X Coral-orange color. -

View Checklist

Mountains and Rivers: Scenic Views of Japan, July 10, 2009-November 1, 2009 The landscape has long been an important part of Japanese art and literature. It was first celebrated in poetry, where invoking the name of a famous location, or meisho, was meant to summon a certain feeling. Later, paintings of these same locations would bring to mind their well-known poetic and literary history. Together, the poems and imagery comprised a canon of place and sentiment, as the same meisho were rendered again and again. During the Edo period (1603–1868) the landscape genre, initially available only to the elite, spread to the medium of woodblock printing, the art of commoner culture. In the 19th century, when most of the works in this exhibition were made, several factors led to the rise of the landscape genre in woodblock prints. Up to this time, the staples of the woodblock print medium had been images of beautiful courtesans and handsome kabuki theater actors. First among these factors was the rising popularity of domestic travel. The development of a system of major roads allowed many people to travel for both business and pleasure. Woodblock prints of locations along these travel routes could function as souvenirs for those who made the trip or as fantasy for those who could not. Rather than evoking a poetic past, these images of meisho were meant to tantalize viewers into imagining romantic far-off places. Another factor in the growth of the genre was the skill of two particular woodblock print artists— Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849) and Utagawa Hiroshige (1797–1858) (whose works are heavily represented here). -

Leca, Radu (2015) the Backward Glance : Concepts of ‘Outside’ and ‘Other’ in the Japanese Spatial Imaginary Between 1673 and 1704

Leca, Radu (2015) The backward glance : concepts of ‘outside’ and ‘other’ in the Japanese spatial imaginary between 1673 and 1704. PhD Thesis. SOAS, University of London http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/23673 Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non‐commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this thesis, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", name of the School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. The Backward Glance: Concepts of ‘Outside’ and ‘Other’ in the Japanese Spatial Imaginary between 1673 and 1704 Radu Leca Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD 2015 Department of the History of Art and Archaeology SOAS, University of London 1 Declaration I have read and understood regulation 17.9 of the Regulations for students of the SOAS, University of London concerning plagiarism. I undertake that all the material presented for examination is my own work and has not been written for me, in whole or in part, by any other person. I also undertake that any quotation or paraphrase from the published or unpublished work of another person has been duly acknowledged in the work which I present for examination. -

Incidence Survey of Kawasaki Disease in 1997 and 1998 in Japan

Incidence Survey of Kawasaki Disease in 1997 and 1998 in Japan Hiroshi Yanagawa, MD*; Yosikazu Nakamura, MD, MPH‡; Mayumi Yashiro‡; Izumi Oki, MD‡; Shizuhiro Hirata, MD‡; Tuohong Zhang, MD§; and Tomisaku Kawasaki, MDʈ ABSTRACT. Objective. To describe the results of a been finalized. This article reports the basic analysis nationwide epidemiologic survey of Kawasaki disease of the survey. for the 2-year period 1997 and 1998. Design. We sent a questionnaire to all hospitals with METHODS 100 beds or more throughout Japan (2663 hospitals) re- The participants of this survey are KD patients who were questing data on patients with Kawasaki disease. Study diagnosed at hospitals with 100 beds or more during the 2-year items included name, sex, date of birth, date of initial study. A questionnaire form was sent to the hospitals with a hospital visit, diagnosis, address, recurrence, sibling pamphlet describing the diagnostic criteria of the disease includ- cases, gammaglobulin treatment, and cardiac lesion in ing color pictures of typical lesions of the skin, eyes, hands, and the acute stage or 1 month after onset. feet. The mailing list of the hospitals for this survey was obtained Results. Of the 2663 hospitals, 68.5% responded, re- from the 1998 hospital directory edited by the Ministry of Health porting 12 966 patients—7489 males and 5477 females. Of and Welfare of the Japanese Government. The number of hospitals the total patients reported, 6373 (incidence rate of 108.0 thus obtained was 2663. per 100 000 children <5 years old) occurred in 1997, and Items included in the questionnaire were name, sex, date of birth, date of initial hospital visit, diagnosis, address, recurrence, 6593 (111.7) in 1998. -

Okakura Kakuzō's Art History: Cross-Cultural Encounters

Asian Review of World Histories 2:1 (January 2014), 17-45 © 2014 The Asian Association of World Historians doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.12773/arwh.2014.2.1.017 Okakura Kakuzō’s Art History: Cross-Cultural Encounters, Hegelian Dialectics and Darwinian Evolution Masako N. RACEL Kennesaw State University Kennesaw, United States [email protected] Abstract Okakura Kakuzō (1863-1913), the founder of the Japan Art Institute, is best known for his proclamation, “Asia is One.” This phrase in his book, The Ideals of the East, and his connections to Bengali revolutionaries resulted in Okakura being remembered as one of Japan’s foremost Pan-Asianists. He did not, how- ever, write The Ideals of the East as political propaganda to justify Japanese aggression; he wrote it for Westerners as an exposition of Japan’s aesthetic heritage. In fact, he devoted much of his life to the preservation and promotion of Japan’s artistic heritage, giving lectures to both Japanese and Western audi- ences. This did not necessarily mean that he rejected Western philosophy and theories. A close examination of his views of both Eastern and Western art and history reveals that he was greatly influenced by Hegel’s notion of dialectics and the evolutionary theories proposed by Darwin and Spencer. Okakura viewed cross-cultural encounters to be a catalyst for change and saw his own time as a critical point where Eastern and Western history was colliding, caus- ing the evolution of both artistic cultures. Key words Okakura Kakuzō, Okakura Tenshin, Hegel, Darwin, cross-cultural encounters, Meiji Downloaded from Brill.com10/02/2021 09:32:22PM via free access 18 | ASIAN REVIEW OF WORLD HISTORIES 2:1 (JANUARY 2014) In 1902, a man dressed in an exotic cloak and hood was seen travel- ing in India. -

2I Fireworks Contract.Pdf

City Council Agenda: 03/222021 2I. Consideration of approving a two-year contract to RES Specialty Pyrotechnics for the Riverfest fireworks display for a total of $20,000 Prepared by: Meeting Date: ☐ Regular Agenda Parks Superintendent 03/22/21 Item ☒ Consent Agenda Item Reviewed by: Approved by: PW Director/ City Engineer City Administrator Finance Director ACTION REQUESTED Consideration of approving a two-year contract to RES Specialty Pyrotechnics for the Riverfest fireworks display for a total of $20,000. REFERENCE AND BACKGROUND The Annual Riverfest event is the largest city celebration of the year and is hosted by volunteer organizations within the City of Monticello. Since 2009, RES Specialty Pyrotechnics has been the fireworks vendor for the Riverfest fireworks display. Currently, RES Specialty Pyrotechnics contract has expired, and staff is asking city council to extend a two-year contract with RES Specialty Pyrotechnics. It should also be noted that the Monticello School District has granted permission to RES for use of the high school property for the fireworks show. Only one proposal was received due to the difficulty in comparing fireworks presentations without defining a price point. Budget Impact: The City of Monticello has been financing the annual fireworks display from the Liquor Store Fund with a 2021 budget of $10,000. I. Staff Workload Impact: Minimum staff workload impacts for fire department review and Public Works to work with the company to section off the staging area. II. Comprehensive Plan Impact Builds Community. STAFF RECOMMENDED ACTION City staff recommends approving a two-year contract to RES Specialty Pyrotechnics for the Riverfest fireworks Display for a total of $20,000. -

Ran In-Ting's Watercolors

Ran In-Ting’s Watercolors East and West Mix in Images of Rural Taiwan May 28–August 14, 2011 Ran In-Ting (Chinese, Taiwan, 1903–1979) Dragon Dance, 1958 Watercolor (81.20) Gift of Margaret Carney Long and Howard Rusk Long in memory of the Boone County Long Family Ran In-Ting (Chinese, Taiwan, 1903–1979) Market Day, 1956 Watercolor (81.6) Gift of Margaret Carney Long and Howard Rusk Long in memory of the Boone County Long Family Mary Pixley Associate Curator of European and American Art his exhibition focuses on the art of the painter Ran In-Ting (Lan Yinding, 1903–1979), one of Taiwan’s most famous T artists. Born in Luodong town of Yilan county in northern Taiwan, he first learned ink painting from his father. After teach- ing art for several years, he spent four years studying painting with the important Japanese watercolor painter Ishikawa Kinichiro (1871–1945). Ran’s impressionistic watercolors portray a deeply felt record With a deep understanding of Chinese brushwork and the of life in Taiwan, touching on the natural beauty of rural life and elegant watercolor strokes of Ishikawa, Ran developed a unique vivacity of the suburban scene. Capturing the excitement of a style that emphasized the changes in fluidity of ink and water- dragon dance with loose and erratic strokes, the mystery and color. By mastering both wet and dry brush techniques, he suc- magic of the rice paddies with flowing pools of color, and the ceeded at deftly controlling the watery medium. Complementing shimmering foliage of the forests with a rainbow of colors and this with a wide variety of brushstrokes and the use of bold dextrous strokes, his paintings are a vivid interpretation of his colors, Ran created watercolors possessing an elegant richness homeland. -

Chapter5: Ainsworth's Beloved Hiroshige

No. Artist Title Date Around Tenpō 14-Kōka 1 150 Utagawa Kuniyoshi Min Zigian (Binshiken), from the series A Mirror for Children of the Twenty-four Paragons of Filial Piety (c.1843-44) 151 Utagawa Kuniyoshi The Ghosts of the Slain Taira Warriors in Daimotsunoura Bay Around Kaei 2-4 (c.1849-51) Around Tenpō 14-Kōka 3 152 Keisai Eisen View of Kegon Waterfall, from the series Famous Places in the Mountains of Nikkō (c.1843-46) Chapter5: Ainsworth's Beloved Hiroshige 153 Utagawa Hiroshige Leafy Cherry Trees on the Sumidagawa River, from the series Famous Places in the Eastern Capital Around Tenpō 2 (c.1831) 154 Utagawa Hiroshige First Cuckoo of the Year at Tsukuda Island, from the series Famous Places in the Eastern Capital Around Tenpō 2 (c.1831) Clearing Weather at Awazu, Night Rain at Karasaki, Autumn Moon at Ishiyamadera Temple, Descending 155-162 Utagawa Hiroshige Geese at Katada, Sunset Glow at Seta, Returning Sails at Yabase, Evening Bell at Mii–dera Temple, Around Tenpō 2-3 (c.1831-32) Evening Snow at Hira, from the series Eight Views of Ōmi 163-164 Utagawa Hiroshige Morning Scene of Nihonbashi Bridge, from the series Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō Road Around Tenpō 5 (c.1834) 165 Utagawa Hiroshige A Procession Sets Out at Nihonbashi Bridge, from the series Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō Road Around Tenpō 5-6 (c.1834-35) 166 Utagawa Hiroshige Morning Mist at Mishima, from the series Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō Road Around Tenpō 5 (c.1834) 167 Utagawa Hiroshige Twilight at Numazu, from the series Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō Road Around Tenpō 5-6 (c.1834-35) 168 Utagawa Hiroshige Mt. -

PHILIPP FRANZ VON SIEBOLD and the OPENING of JAPAN Philipp Franz Von Siebold, 1860 PHILIPP FRANZ VON SIEBOLD and the OPENING of JAPAN • a RE-EVALUATION •

PHILIPP FRANZ VON SIEBOLD AND THE OPENING OF JAPAN Philipp Franz von Siebold, 1860 PHILIPP FRANZ VON SIEBOLD AND THE OPENING OF JAPAN • A RE-EVALUATION • HERBERT PLUTSCHOW Josai International University PHILIPP FRANZ VON SIEBOLD AND THE OPENING OF JAPAN Herbert Plutschow First published in 2007 by GLOBAL ORIENTAL LTD PO Box 219 Folkestone Kent CT20 2WP UK www.globaloriental.co.uk © Herbert Plutschow 2007 ISBN 978-1-905246-20-5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP catalogue entry for this book is available from the British Library Set in 9.5/12pt Stone Serif by Servis Filmsetting Ltd, Manchester Printed and bound in England by Cromwell Press Ltd, Trowbridge, Wilts. Contents Preface vii 1. Von Siebold’s First Journey to Japan 1 • Journey to Edo 9 • The Siebold Incident 16 2. Von Siebold the Scholar 26 • Nippon 26 • The Siebold Collection 30 3. Von Siebold and the Opening of Japan 33 •Von Siebold and the Dutch Efforts to Open Japan 33 •Von Siebold and the American Expedition to Japan 47 •Von Siebold and the Russian Expedition to Japan 80 4. Von Siebold’s Second Journey to Japan 108 •Shogunal Adviser 115 • Attack on the British Legation 120 • The Tsushima Incident 127 • Banished Again 137 5. Back in Europe 149 • Advising Russia 149 • Opinion-maker 164 • Advising France and Japan 171 •Von Siebold’s Death 178 6. -

Catalogue 229 Japanese and Chinese Books, Manuscripts, and Scrolls Jonathan A. Hill, Bookseller New York City

JonathanCatalogue 229 A. Hill, Bookseller JapaneseJAPANESE & AND Chinese CHINESE Books, BOOKS, Manuscripts,MANUSCRIPTS, and AND ScrollsSCROLLS Jonathan A. Hill, Bookseller Catalogue 229 item 29 Catalogue 229 Japanese and Chinese Books, Manuscripts, and Scrolls Jonathan A. Hill, Bookseller New York City · 2019 JONATHAN A. HILL, BOOKSELLER 325 West End Avenue, Apt. 10 b New York, New York 10023-8143 telephone: 646-827-0724 home page: www.jonathanahill.com jonathan a. hill mobile: 917-294-2678 e-mail: [email protected] megumi k. hill mobile: 917-860-4862 e-mail: [email protected] yoshi hill mobile: 646-420-4652 e-mail: [email protected] member: International League of Antiquarian Booksellers, Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America & Verband Deutscher Antiquare terms are as usual: Any book returnable within five days of receipt, payment due within thirty days of receipt. Persons ordering for the first time are requested to remit with order, or supply suitable trade references. Residents of New York State should include appropriate sales tax. printed in china item 24 item 1 The Hot Springs of Atami 1. ATAMI HOT SPRINGS. Manuscript on paper, manuscript labels on upper covers entitled “Atami Onsen zuko” [“The Hot Springs of Atami, explained with illustrations”]. Written by Tsuki Shirai. 17 painted scenes, using brush and colors, on 63 pages. 34; 25; 22 folding leaves. Three vols. 8vo (270 x 187 mm.), orig. wrappers, modern stitch- ing. [ Japan]: late Edo. $12,500.00 This handsomely illustrated manuscript, written by Tsuki Shirai, describes and illustrates the famous hot springs of Atami (“hot ocean”), which have been known and appreciated since the 8th century.