The Development of Facial Likeness in Kabuki Actor Prints

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japanese Woodblock Prints at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston Hokusai Exhibit 2015 Tokugawa Ieyasu Tokugawa Clan Rules 1615- 1850

From the Streets to the Galleries: Japanese Woodblock Prints at the Museum of Fine Arts Boston Hokusai Exhibit 2015 Tokugawa Ieyasu Tokugawa Clan Rules 1615- 1850 Kabuki theater Utamaro: Moon at Shinagawa (detail), 1788–1790 Brothel City Fashions UTAGAWA KUNIYOSHI, TAKEOUT SUSHI SUGGESTING ATAKA, ABOUT 1844 A Young Man Dallying with a Courtesan about 1680 attributed to Hishikawa Moronobu Book of Prints – Pinnacle of traditional woodblock print making Driving Rain at Shono, Station 46, from the Fifty-three Stations of the Tokkaido Road, 1833, Ando Hiroshige Actor Kawarazaki Gonjuro I as Danshichi 1860, Artist: Kunisada The In Demand Type from the series Thirty Two Physiognomic Types in the Modern World Artist: Utagawa Kunisada 1820s The Mansion of the Plates, From the Series One Hundred Ghost Stories, about 1831, Artist Katsushika Hokusai Taira no Tadanori, from the Series Warriors as Six Poetic Immortals Artist Yashima Gakutei, About 1827, Surimono Meiji Restoration. Forecast for the Year 1890, 1883, Ogata Gekko Young Ladies Looking at Japanese objects, 1869 by James Tissot La Japonaise (Camille Monet in Japanese costume) Claude Monet, 1876 The Fish, Stained glass Window, 1890, John La Farge Academics and Adventurers: Edward S. Morse, Okakura Kakuzo, Ernest Fenollosa, William Sturgis Bigelow New Age Japanese woman, About 1930s Edward Sylvester Morse Whaleback Shell Midden in Damariscotta, Maine Brachiopod Shell Brachiopod worm William Sturgis Bigelow Ernest Fenollosa Okakura Kakuzo Charles T. Spaulding https://www.mfa.org/collections /asia/tour/spaulding-collection Stepping Stones in the Afternoon, Hiratsuka Un’ichi, 1960 Azechi Umetaro, 1954 Reike Iwami, Morning Waves. 1978 Museum of Fine Arts Toulouse Lautrec and the Stars of Paris April 7-August 4 Uniqlo t-shirt. -

Ezra Pound His Metric and Poetry Books by Ezra Pound

EZRA POUND HIS METRIC AND POETRY BOOKS BY EZRA POUND PROVENÇA, being poems selected from Personae, Exultations, and Canzoniere. (Small, Maynard, Boston, 1910) THE SPIRIT OF ROMANCE: An attempt to define somewhat the charm of the pre-renaissance literature of Latin-Europe. (Dent, London, 1910; and Dutton, New York) THE SONNETS AND BALLATE OF GUIDO CAVALCANTI. (Small, Maynard, Boston, 1912) RIPOSTES. (Swift, London, 1912; and Mathews, London, 1913) DES IMAGISTES: An anthology of the Imagists, Ezra Pound, Aldington, Amy Lowell, Ford Maddox Hueffer, and others GAUDIER-BRZESKA: A memoir. (John Lane, London and New York, 1916) NOH: A study of the Classical Stage of Japan with Ernest Fenollosa. (Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1917; and Macmillan, London, 1917) LUSTRA with Earlier Poems. (Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1917) PAVANNES AHD DIVISIONS. (Prose. In preparation: Alfred A. Knopf, New York) EZRA POUND HIS METRIC AND POETRY I "All talk on modern poetry, by people who know," wrote Mr. Carl Sandburg in _Poetry_, "ends with dragging in Ezra Pound somewhere. He may be named only to be cursed as wanton and mocker, poseur, trifler and vagrant. Or he may be classed as filling a niche today like that of Keats in a preceding epoch. The point is, he will be mentioned." This is a simple statement of fact. But though Mr. Pound is well known, even having been the victim of interviews for Sunday papers, it does not follow that his work is thoroughly known. There are twenty people who have their opinion of him for every one who has read his writings with any care. -

EDO PRINT ART and ITS WESTERN INTERPRETATIONS Elizabeth R

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: EDO PRINT ART AND ITS WESTERN INTERPRETATIONS Elizabeth R. Nash, Master of Arts, 2004 Thesis directed by: Professor Sandy Kita Department of Art History and Archaeology This thesis focuses on the disparity between the published definitions and interpretations of the artistic and cultural value of Edo prints to Japanese culture by nineteenth-century French and Americans. It outlines the complexities that arise when one culture defines another, and also contrasts stylistic and cultural methods in the field of art history. Louis Gonse, S. Bing and other nineteenth-century European writers and artists were impressed by the cultural and intellectual achievements of the Tokugawa government during the Edo period, from 1615-1868. Contemporary Americans perceived Edo as a rough and immoral city. Edward S. Morse and Ernest Fenollosa expressed this American intellectual disregard for the print art of the Edo period. After 1868, the new Japanese government, the Meiji Restoration, as well as the newly empowered imperial court had little interest in the art of the failed military government of Edo. They considered Edo’s legacy to be Japan’s technological naïveté. EDO PRINT ART AND ITS WESTERN INTERPRETATIONS by Elizabeth R. Nash Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2004 Advisory Committee: Professor Sandy Kita, Chair Professor Jason Kuo Professor Marie Spiro ©Copyright by Elizabeth R. Nash 2004 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My experience studying art history at the University of Maryland has been both personally and intellectually rewarding. -

Okakura Kakuzō's Art History: Cross-Cultural Encounters

Asian Review of World Histories 2:1 (January 2014), 17-45 © 2014 The Asian Association of World Historians doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.12773/arwh.2014.2.1.017 Okakura Kakuzō’s Art History: Cross-Cultural Encounters, Hegelian Dialectics and Darwinian Evolution Masako N. RACEL Kennesaw State University Kennesaw, United States [email protected] Abstract Okakura Kakuzō (1863-1913), the founder of the Japan Art Institute, is best known for his proclamation, “Asia is One.” This phrase in his book, The Ideals of the East, and his connections to Bengali revolutionaries resulted in Okakura being remembered as one of Japan’s foremost Pan-Asianists. He did not, how- ever, write The Ideals of the East as political propaganda to justify Japanese aggression; he wrote it for Westerners as an exposition of Japan’s aesthetic heritage. In fact, he devoted much of his life to the preservation and promotion of Japan’s artistic heritage, giving lectures to both Japanese and Western audi- ences. This did not necessarily mean that he rejected Western philosophy and theories. A close examination of his views of both Eastern and Western art and history reveals that he was greatly influenced by Hegel’s notion of dialectics and the evolutionary theories proposed by Darwin and Spencer. Okakura viewed cross-cultural encounters to be a catalyst for change and saw his own time as a critical point where Eastern and Western history was colliding, caus- ing the evolution of both artistic cultures. Key words Okakura Kakuzō, Okakura Tenshin, Hegel, Darwin, cross-cultural encounters, Meiji Downloaded from Brill.com10/02/2021 09:32:22PM via free access 18 | ASIAN REVIEW OF WORLD HISTORIES 2:1 (JANUARY 2014) In 1902, a man dressed in an exotic cloak and hood was seen travel- ing in India. -

Publisbing Culture in Eighteentb-Century Japan: the Case of the Edo Publisher Tsutaya Jqzaburô (1751-97)

Publisbing Culture in Eighteentb-Century Japan: The Case of the Edo Publisher Tsutaya JQzaburô (1751-97) Yu Chang A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto 0 Copyright by Yu Chang 1997 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1*1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliogtaphic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellingtm Ottawa ON K1A ON4 OnawaOFJ KlAW Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence diowing the exclusive permettant à la National Librq of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seil reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othenvise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author' s ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT Publishing Culture in Eighteentb-Century Japan: The Case of the Edo Pubüsher Tsutaya Jûzaburô (1750-97) Master of Arts, March 1997 Yu Chang Department of East Asian Studies During the ideologicai program of the Senior Councillor Mitsudaira Sadanobu of the Tokugawa bah@[ governrnent, Tsutaya JÛzaburÔ's aggressive publishing venture found itseif on a collision course with Sadanobu's book censorship policy. -

Ukiyo-E DAIGINJO

EXCLUSIVE JAPANESE IMPORT Ukiyo-e DAIGINJO UKIYO-E BREWERY Ukiyo-e (ooh-kee-yoh-eh) is a Japanese Founded in 1743 in the Nada district of woodblock print or painting of famous Kobe, Hakutsuru is the #1 selling sake kabuki actors, beautiful women, travel brand in Japan. landscapes and city life from the Elegant, thoughtful, and delicious Edo period. Ukiyo-e is significant in sake defines Hakutsuru, but tireless expressing the sensual attributes of innovation places it in a class of its Japanese culture from 17th to 19th own. Whether it’s understanding water century. sources at the molecular level, building a facility to create one-of-a-kind yeast, ARTIST/CHARACTER or developing its own sake-specific rice, Hakutsuru Nishiki, it’s the deep dive into This woodblock print displays the famed research and development that explains kabuki actor, Otani Oniji III, as Yakko Hakutsuru’s ascension to the top of a Edobei in the play, Koi Nyobo Somewake centuries-old craft. Tazuna. The play was performed at the Kawarazakiza theater in May 1794. The artist, Toshusai Sharaku, was known for Brewery Location Hyogo Prefecture creating visually bold prints that gave a Founding Date 1743 Brewmaster Mitsuhiro Kosa revealing look into the world of kabuki. DAIGINJO DAIGINJO DEFINED Just like Ukiyo-e, making beautiful sake Sake made with rice milled to at least takes time, mastery, and creativity. To 50% of its original size, water, koji, and a craft an exquisite sake, such as this small amount of brewers’ alcohol added aromatic and enticing Daiginjo, is both for stylistic purposes. -

Schaftliches Klima Und Die Alte Frau Als Feindbild

6 Zusammenfassung und Schluss: Populärkultur, gesell- schaftliches Klima und die alte Frau als Feindbild Wie ein extensiver Streifzug durch die großstädtische Populärkultur der späten Edo-Zeit gezeigt hat, tritt darin etwa im letzten Drittel der Edo-Zeit der Typus hässlicher alter Weiber mit zahlreichen bösen, ne- gativen Eigenschaften in augenfälliger Weise in Erscheinung. Unter Po- pulärkultur ist dabei die Dreiheit gemeint, die aus dem volkstümlichen Theater Kabuki besteht, den polychromen Holzschnitten, und der leich- ten Lektüre der illustrierten Romanheftchen (gōkan) und der – etwas gehobenere Ansprüche bedienenden – Lesebücher (yomihon), die mit einem beschränkten Satz von Schriftzeichen auskamen und der Unter- haltung und Erbauung vornehmlich jener Teile der Bevölkerung dien- ten, die nur eine einfache Bildung genossen hatten. Durch umherziehen- de Leihbuchhändler fand diese Art der Literatur auch über den groß- städtischen Raum hinaus bis hin in die kleineren Landflecken und Dör- fer hinein Verbreitung. Die drei Medien sind vielfach verschränkt: Holzschnitte dienen als Werbemittel für bzw. als Erinnerungsstücke an Theateraufführungen; Theaterprogramme sind reich illustrierte kleine Holzschnittbücher; die Stoffe der Theaterstücke werden in den zahllo- sen Groschenheften in endlosen Varianten recyclet; in der Heftchenlite- ratur spielt die Illustration eine maßgebliche Rolle, die Illustratoren sind dieselben wie die Zeichner der Vorlagen für die Holzschnitte; in einigen Fällen sind Illustratoren und Autoren identisch; Autoren steuern Kurz- texte als Legenden für Holzschnitte bei. Nachdrücklich muss der kommerzielle Aspekt dieser „Volkskultur“ betont werden. In allen genannten Sparten dominieren Auftragswerke, die oft in nur wenigen Tagen erledigt werden mussten. Die Theaterbe- treiber ließen neue Stücke schreiben oder alte umschreiben beziehungs- weise brachten Kombinationen von Stücken zur Aufführung, von wel- chen sie sich besonders viel Erfolg versprachen. -

Extreme Japan

Extreme Japan At its roots, Japan has two deities who represent opposite extremes – Amaterasu, a Nigitama (peaceful spirit), and Susanoo, an Aratama (wrathful spirit). The dichotomy can be seen reflected in various areas of the culture. There is Kinkaku-ji (the Golden Pavilion) to represent the Kitayama culture, and Ginkaku-ji (the Silver Pavilion) to represent the Higashiyama culture. Kabuki has its wagoto (gentle style) and aragoto (bravura style). There are the thatched huts of wabicha (frugal tea ceremony) as opposed to the golden tea ceremony houses. Japan can be punk – flashy and noisy. Or, it can be bluesy – deep and tranquil. Add to flash, the kabuki way. Subtract to refine, the wabi way. Just don’t hold back - go to the extreme.Either way, it’s Japan. Japan Concept 5 Kabuku Japan Concept 6 wabi If we awaken and recapture the basic human passions that are today being lost in each moment, new Japanese traditions will be passed on with a bold, triumphant face. Taro Okamoto, Nihon no Dento (Japanese Tradition) 20 kabuku Extreme Japan ① Photograph: Satoshi Takase ③ ② Eccentrics at the Cutting Edge of Fashion ① Lavish preferences of truck drivers are reflected in vehicles decorated like illuminated floats. ② The crazy KAWAII of Kyary Pamyu Pamyu. ③ The band KISHIDAN. Yankii style, characterized by tsuppari hairstyles and customized high ⑤ school uniforms. ④ Kabuki-style cosmetic face masks made by Imabari Towel. Kabuki’s Kumadori is a powerful makeup for warding off evil spirits. ⑤ Making lavish use of combs and hairpins, oiran were the fashion leaders of Edo. The “face-showing” event is a glimpse into the sleepless world of night. -

Analyzing the Outrageous: Takehara Shunchōsai’S Shunga Book Makura Dōji Nukisashi Manben Tamaguki (Pillow Book for the Young, 1776)

Japan Review 26 Special Issue Shunga (2013): 169–93 Analyzing the Outrageous: Takehara Shunchōsai’s Shunga Book Makura dōji nukisashi manben tamaguki (Pillow Book for the Young, 1776) C. Andrew GERSTLE This article examines the book Makura dōji nukisashi manben tamaguki (1776) with illustrations by Takehara Shunchōsai in the context of a sub-genre of shunga books—erotic parodies of educational textbooks (ōrai- mono)—produced in Kyoto and Osaka in the second half of the eighteenth century. A key question is whether we should read this irreverent parody as subversive to the political/social order, and if so in what way. Different from the erotic parodies by Tsukioka Settei, which focused mostly on women’s conduct books, this work is a burlesque parody of a popular educational anthology textbook used more for boys. It depicts iconic historical figures, men and women, courtiers, samurai and clerics all as ob- sessed with lust, from Shōtoku Taishi, through Empresses and Kōbō Daishi to Minamoto no Yoshitsune. The article considers whether recent research on Western parody as polemic is relevant to an analysis of this and other Edo period parodies. The article also considers the view, within Japanese scholarship, on the significance of parody (mojiri, yatsushi, mitate) in Edo period arts. The generation of scholars during and immediately after World War II, such as Asō Isoji (1896–1979) and Teruoka Yasutaka (1908–2001) tended to view parody and humor as a means to attack the Tokugawa sys- tem, but more recent research has tended to eschew such interpretations. The article concludes by placing this work among other irreverent writing/art of the 1760s–1780s, in both Edo and Kyoto/Osaka, which was provocative and challenged the Tokugawa system. -

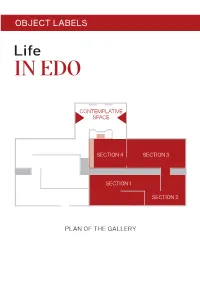

Object Labels

OBJECT LABELS CONTEMPLATIVE SPACE SECTION 4 SECTION 3 SECTION 1 SECTION 2 PLAN OF THE GALLERY SECTION 1 Travel Utagawa Hiroshige Procession of children passing Mount Fuji 1830s Hiroshige playfully imitates with children a procession of a daimyo passing Mt Fuji. A popular subject for artists, a daimyo and his entourage could make for a lively scene. During Edo, daimyo were required to travel to Edo City every other year and live there under the alternate attendance (sankin- kōtai) system. Hundreds of retainers would transport weapons, ceremonial items, and personal effects that signal the daimyo’s military and financial might. Some would be mounted on horses; the daimyo and members of his family carried in palanquins. Cat. 5 Tōshūsai Sharaku Actor Arashi Ryūzō II as the Moneylender Ishibe Kinkichi 1794 Kabuki actor portraits were one of the most popular types of ukiyo-e prints. Audiences flocked to see their favourite kabuki performers, and avidly collected images of them. Actors were stars, celebrities much like the idols of today. Sharaku was able to brilliantly capture an actor’s performance in his expressive portrayals. This image illustrates a scene from a kabuki play about a moneylender enforcing payment of a debt owed by a sick and impoverished ronin and his wife. The couple give their daughter over to him, into a life of prostitution. Playing a repulsive figure, the actor Ryūzō II made the moneylender more complex: hard-hearted, gesturing like a bully – but his eyes reveal his lack of confidence. The character is meant to be disliked by the audience, but also somewhat comical. -

2019/10/30 Edo-Tokyo Museum News 15

English Edition15 Oct. 25 Fri. 2019 No.15 Special Exhibition Saturday, September 14, to Monday, November 4 — Peacekeeping Contributors Special Exhibition Gallery, 1F Samurai in Edo Period *Displays will be changed during the exhibition. A matchlock that could be used on horseback. Horseback matchlock, bullet cases, bullets and priming powder that belonged to NONOMURA Ichinoshin End of Edo period Information Hours: 9:30 – 17:30 (until 19:30 on Saturdays). Last admission 30 minutes before closing. Closed: Mondays (except for September 23, October 14, and November 4), Tuesday, September 24, and Tuesday, October 15. Look at these Organaization: Tokyo Metropolitan Foundation for History and Culture Tokyo Metropolitan Edo-Tokyo Museum, dignied fellows The Asahi Shimbun. — these are samurai ! Admission: ‘Ofcials Belonging to Admission Fee (tax included) Special exhibition only Special and permanent exhibition the Satsuma Domain’ Standard adult ¥1,100 (¥880) ¥1,360 (¥1,090) University/college students ¥880 (¥700) ¥1,090 (¥870) Photographer: Felice Beato c. 1863–1870 Middle and high school students. Seniors 65+ ¥550 (¥440) ¥680 (¥550) Private collection Tokyo middle school students and elementary school students ¥550 (¥440) None Notes: • Fees in parentheses are for groups of twenty or more. “Samurai” is a key word used oen to dene the image of Japan, both at home and abroad. at • Fees are waived in the following cases: Children below school age and individuals with a Shintai Shogaisha Techo (Physical Disability Certicate), Ai-no-Techo (Intellectual Disability Certicate), Ryoiku Techo (Rehabilitation Certicate), Seishin Shogaisha Hoken Fukushi Techo words associations, however, vary from person to person. A member of the samurai class, a (Certicate for Health and Welfare of People with Mental Disorders), or Hibakusha Kenko Techo (Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certicate) and up to two people accompanying them. -

Title Japonisme in Polish Pictorial Arts (1885 – 1939) Type Thesis URL

Title Japonisme in Polish Pictorial Arts (1885 – 1939) Type Thesis URL http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/6205/ Date 2013 Citation Spławski, Piotr (2013) Japonisme in Polish Pictorial Arts (1885 – 1939). PhD thesis, University of the Arts London. Creators Spławski, Piotr Usage Guidelines Please refer to usage guidelines at http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/policies.html or alternatively contact [email protected]. License: Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Unless otherwise stated, copyright owned by the author Japonisme in Polish Pictorial Arts (1885 – 1939) Piotr Spławski Submitted as a partial requirement for the degree of doctor of philosophy awarded by the University of the Arts London Research Centre for Transnational Art, Identity and Nation (TrAIN) Chelsea College of Art and Design University of the Arts London July 2013 Volume 1 – Thesis 1 Abstract This thesis chronicles the development of Polish Japonisme between 1885 and 1939. It focuses mainly on painting and graphic arts, and selected aspects of photography, design and architecture. Appropriation from Japanese sources triggered the articulation of new visual and conceptual languages which helped forge new art and art educational paradigms that would define the modern age. Starting with Polish fin-de-siècle Japonisme, it examines the role of Western European artistic centres, mainly Paris, in the initial dissemination of Japonisme in Poland, and considers the exceptional case of Julian Żałat, who had first-hand experience of Japan. The second phase of Polish Japonisme (1901-1918) was nourished on local, mostly Cracovian, infrastructure put in place by the ‘godfather’ of Polish Japonisme Żeliks Manggha Jasieski. His pro-Japonisme agency is discussed at length.