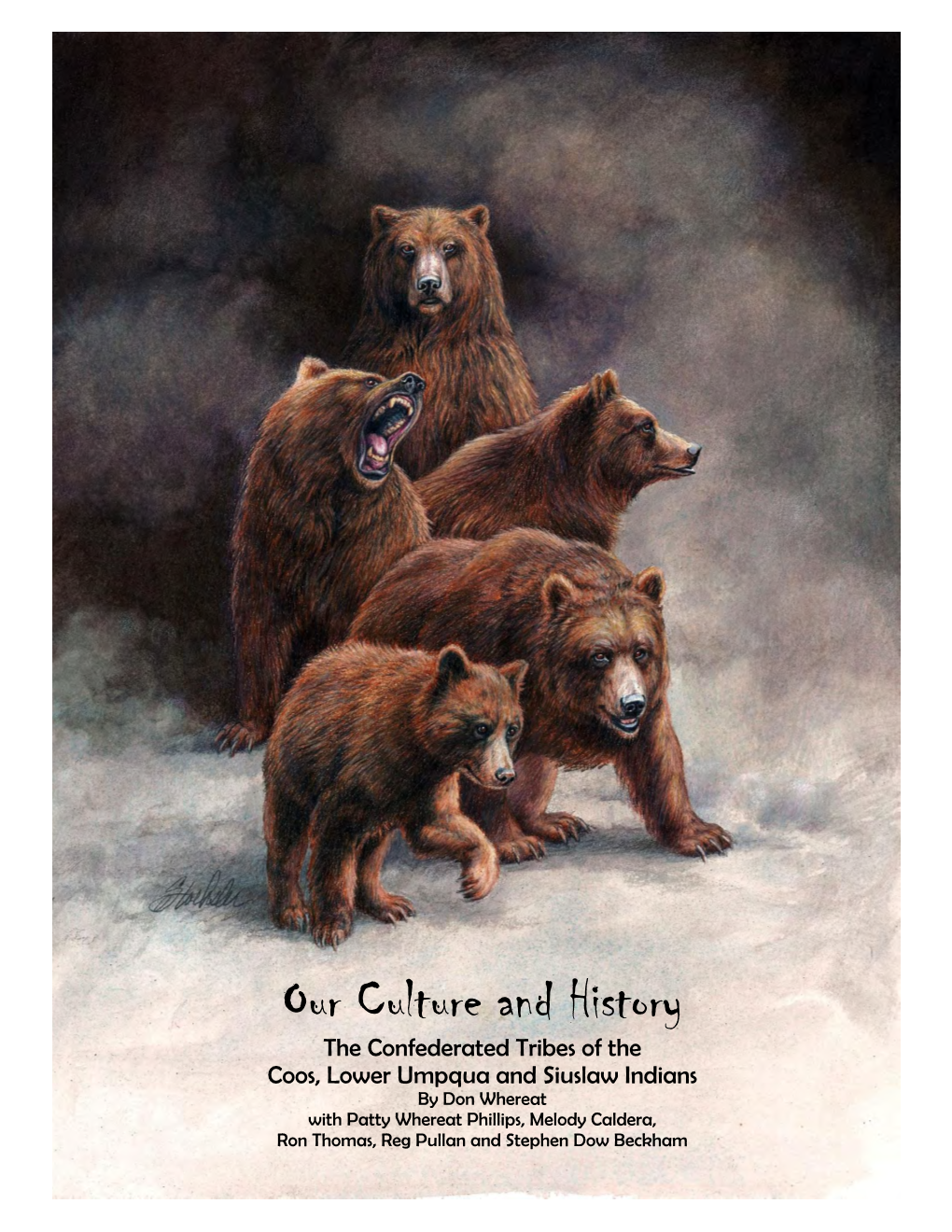

Our Culture and History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diary of William a Quantz © Lived 1854 – 1945

Diary of William A Quantz © Lived 1854 – 1945 Volume 6 1920 – 1922 Source and Copy Reference Information While copyright and ownership remains with all direct descendants of William A. Quantz, the family welcomes inquiries from readers about additional usage consistent with the spirit and purposes as stated by the author." You can contact us at [email protected]. Note: Starting with volume 5 the page numbers started at 1 again. Volume 6 starts at page 127. Page 127 1920 - Happy New Year - 1920 A bright new year and a sunny track Along and upward way, And a song of praise on looking back Wednesday year has passed away, And golden sheaves, nor small north you, This is my New Year’s wish for you. January 3:. Last Sunday I went up to the First Christian Church on Bathurst Street, and heard Morton preach. Went home with him for dinner and had a good visit. Monday Flo and I went up to cousin Jake Quantz’s at Edgely. Had another good visit and came back to the city on Wednesday in Joe Quantz’s car with them. New Year’s Day was spent with the girls again and yesterday we came home. Brother Ed is down from Alberta and he brought Minnie Ruth from Wellington’s and I expect they will be with us for some time. January 10:. We are enjoying ourselves at home once more. Ed and Minnie are here and we are doing as much visiting as work. The weather has been cold and it seems to be a cozy place in the bay-window over the register. -

Native Peoples of North America

Native Peoples of North America Dr. Susan Stebbins SUNY Potsdam Native Peoples of North America Dr. Susan Stebbins 2013 Open SUNY Textbooks 2013 Susan Stebbins This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. Published by Open SUNY Textbooks, Milne Library (IITG PI) State University of New York at Geneseo, Geneseo, NY 14454 Cover design by William Jones About this Textbook Native Peoples of North America is intended to be an introductory text about the Native peoples of North America (primarily the United States and Canada) presented from an anthropological perspective. As such, the text is organized around anthropological concepts such as language, kinship, marriage and family life, political and economic organization, food getting, spiritual and religious practices, and the arts. Prehistoric, historic and contemporary information is presented. Each chapter begins with an example from the oral tradition that reflects the theme of the chapter. The text includes suggested readings, videos and classroom activities. About the Author Susan Stebbins, D.A., Professor of Anthropology and Director of Global Studies, SUNY Potsdam Dr. Susan Stebbins (Doctor of Arts in Humanities from the University at Albany) has been a member of the SUNY Potsdam Anthropology department since 1992. At Potsdam she has taught Cultural Anthropology, Introduction to Anthropology, Theory of Anthropology, Religion, Magic and Witchcraft, and many classes focusing on Native Americans, including The Native Americans, Indian Images and Women in Native America. Her research has been both historical (Traditional Roles of Iroquois Women) and contemporary, including research about a political protest at the bridge connecting New York, the Akwesasne Mohawk reservation and Ontario, Canada, and Native American Education, particularly that concerning the Native peoples of New York. -

Lower Alsea River Watershed Analysis

Table of Contents Executive Summary .................................................. iii List of Tables ....................................................... xx List of Figures ..................................................... xxii List of Maps ...................................................... xxiii Chapter 1 - Characterization ............................................ 1 Chapter 2 - Issues and Key Questions ..................................... 6 Chapter 3 - Reference and Current Conditions ............................. 10 Forest Fragmentation ............................................ 10 Aquatic Habitat ................................................. 32 Human Uses ................................................... 72 Chapter 4 - Interpretation/Findings and Recommendations ................... 86 References ......................................................... 96 Appendices ........................................................ 103 Map Packet ........................................... (following p. 123) Page ii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Characterization: The Analysis Area The Lower Alsea River watershed, located in the Alsea River Basin, encompasses about 98,470 land acres of the western Oregon Coast Range mountains along the lower Alsea River in Benton and Lincoln counties (Map 1: “Alsea Basin and Lower Alsea Analysis Area”). The watershed, with State Highway 34 running through it, stretches from Waldport on the coast to the inland town of Alsea. About 14 per cent of the watershed (13,786 acres) is managed by the Bureau -

Self-Guiding Geology Tour of Stanley Park

Page 1 of 30 Self-guiding geology tour of Stanley Park Points of geological interest along the sea-wall between Ferguson Point & Prospect Point, Stanley Park, a distance of approximately 2km. (Terms in bold are defined in the glossary) David L. Cook P.Eng; FGAC. Introduction:- Geomorphologically Stanley Park is a type of hill called a cuesta (Figure 1), one of many in the Fraser Valley which would have formed islands when the sea level was higher e.g. 7000 years ago. The surfaces of the cuestas in the Fraser valley slope up to the north 10° to 15° but approximately 40 Mya (which is the convention for “million years ago” not to be confused with Ma which is the convention for “million years”) were part of a flat, eroded peneplain now raised on its north side because of uplift of the Coast Range due to plate tectonics (Eisbacher 1977) (Figure 2). Cuestas form because they have some feature which resists erosion such as a bastion of resistant rock (e.g. volcanic rock in the case of Stanley Park, Sentinel Hill, Little Mountain at Queen Elizabeth Park, Silverdale Hill and Grant Hill or a bed of conglomerate such as Burnaby Mountain). Figure 1: Stanley Park showing its cuesta form with Burnaby Mountain, also a cuesta, in the background. Page 2 of 30 Figure 2: About 40 million years ago the Coast Mountains began to rise from a flat plain (peneplain). The peneplain is now elevated, although somewhat eroded, to about 900 metres above sea level. The average annual rate of uplift over the 40 million years has therefore been approximately 0.02 mm. -

Characterizing Tribal Cultural Landscapes, Volume II: Tribal Case

OCS Study BOEM 2017-001 Characterizing Tribal Cultural Landscapes Volume II: Tribal Case Studies US Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Pacific OCS Region This page intentionally left blank. OCS Study BOEM 2017-001 Characterizing Tribal Cultural Landscapes Volume II: Tribal Case Studies David Ball Rosie Clayburn Roberta Cordero Briece Edwards Valerie Grussing Janine Ledford Robert McConnell Rebekah Monette Robert Steelquist Eirik Thorsgard Jon Townsend Prepared under BOEM-NOAA Interagency Agreement M12PG00035 by National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Office of National Marine Sanctuaries 1305 East-West Highway, SSMC4 Silver Spring, MD 20910 Makah Tribe Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde Community of Oregon Yurok Tribe National Marine Sanctuary Foundation US Department of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Office of National Marine Sanctuaries US Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Pacific OCS Region December 31, 2017 This page intentionally left blank. DISCLAIMER This study was funded, in part, by the US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), Pacific Outer Continental Shelf (OCS) Region, Camarillo, CA, through Interagency Agreement Number M12PG00035 with the US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). This report has been technically reviewed by BOEM and it has been approved for publication. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the US Government, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. REPORT AVAILABILITY This report can be downloaded from the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management’s Recently Completed Environmental Studies – Pacific webpage at https://www.boem.gov/Pacific-Completed-Studies/. -

Volume I: Trail Maps, Research Methods & Historical Accounts

Coquille Indian Tribe Cultural Geography Project Coquelle Trails: Early Historical Roads and Trails of Ancestral Coquille Indian Lands, 1826 - 1875 Volume I: Trail Maps, Research Methods & Historical Accounts Report Prepared by: Bob Zybach, Program Manager Oregon Websites and Watersheds Project, Inc. & Don Ivy, Manager Coquille Indian Tribe Historic Preservation Office – Cultural Resources Program North Bend, Oregon January 4, 2013 Preface Coquelle Trails: Early Historical Roads and Trails of Ancestral Coquille Indian Lands, 1826 - 1875 renews a project originally started in 2006 to investigate and publish a “cultural geography” of the modern Coquille Indian Tribe: a description of the physical landscape and geographic area occupied or utilized by the Ancestors of the modern Coquille Tribe prior to -- and at the time of -- the earliest reported contacts with Europeans and Euro- Americans. Coquelle Trails is the first of what is expected to be several installments that will complete this renewed Cultural Geography Project. Although ships and sailors made contact with Indians in earlier years, the focus of this report begins with the first historical land-based contacts between Indians and foreigners along the rivers and beaches of Oregon’s south coast. Those few and brief encounters are documented in poorly written and often incomplete journals of men who, without maps or a true fix on their locations, wandered into and across the lands of Hanis, Miluk, and Athapaskan speaking Indians in what is today Coos and Curry Counties. Those wanderings were the first surges of the tidal wave of America’s Manifest Destiny that would soon wash over the Indians and their country. -

Click Here to Download the 4Th Grade Curriculum

Copyright © 2014 The Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde Community of Oregon. All rights reserved. All materials in this curriculum are copyrighted as designated. Any republication, retransmission, reproduction, or sale of all or part of this curriculum is prohibited. Introduction Welcome to the Grand Ronde Tribal History curriculum unit. We are thankful that you are taking the time to learn and teach this curriculum to your class. This unit has truly been a journey. It began as a pilot project in the fall of 2013 that was brought about by the need in Oregon schools for historically accurate and culturally relevant curriculum about Oregon Native Americans and as a response to countless requests from Oregon teachers for classroom- ready materials on Native Americans. The process of creating the curriculum was a Tribal wide effort. It involved the Tribe’s Education Department, Tribal Library, Land and Culture Department, Public Affairs, and other Tribal staff. The project would not have been possible without the support and direction of the Tribal Council. As the creation was taking place the Willamina School District agreed to serve as a partner in the project and allow their fourth grade teachers to pilot it during the 2013-2014 academic year. It was also piloted by one teacher from the Pleasant Hill School District. Once teachers began implementing the curriculum, feedback was received regarding the effectiveness of lesson delivery and revisions were made accordingly. The teachers allowed Tribal staff to visit during the lessons to observe how students responded to the curriculum design and worked after school to brainstorm new strategies for the lessons and provide insight from the classroom teacher perspective. -

2010 General Management Plan

Montezuma Castle National Monument National Park Service Mo n t e z u M a Ca s t l e na t i o n a l Mo n u M e n t • tu z i g o o t na t i o n a l Mo n u M e n t Tuzigoot National Monument U.S. Department of the Interior ge n e r a l Ma n a g e M e n t Pl a n /en v i r o n M e n t a l as s e s s M e n t Arizona M o n t e z u MONTEZU M A CASTLE MONTEZU M A WELL TUZIGOOT M g a e n e r a l C a s t l e M n a n a g e a t i o n a l M e n t M P o n u l a n M / e n t e n v i r o n • t u z i g o o t M e n t a l n a a t i o n a l s s e s s M e n t M o n u M e n t na t i o n a l Pa r k se r v i C e • u.s. De P a r t M e n t o f t h e in t e r i o r GENERAL MANA G E M ENT PLAN /ENVIRON M ENTAL ASSESS M ENT General Management Plan / Environmental Assessment MONTEZUMA CASTLE NATIONAL MONUMENT AND TUZIGOOT NATIONAL MONUMENT Yavapai County, Arizona January 2010 As the responsible agency, the National Park Service prepared this general management plan to establish the direction of management of Montezuma Castle National Monument and Tu- zigoot National Monument for the next 15 to 20 years. -

Indian Country Welcome To

Travel Guide To OREGON Indian Country Welcome to OREGON Indian Country he members of Oregon’s nine federally recognized Ttribes and Travel Oregon invite you to explore our diverse cultures in what is today the state of Oregon. Hundreds of centuries before Lewis & Clark laid eyes on the Pacific Ocean, native peoples lived here – they explored; hunted, gathered and fished; passed along the ancestral ways and observed the ancient rites. The many tribes that once called this land home developed distinct lifestyles and traditions that were passed down generation to generation. Today these traditions are still practiced by our people, and visitors have a special opportunity to experience our unique cultures and distinct histories – a rare glimpse of ancient civilizations that have survived since the beginning of time. You’ll also discover that our rich heritage is being honored alongside new enterprises and technologies that will carry our people forward for centuries to come. The following pages highlight a few of the many attractions available on and around our tribal centers. We encourage you to visit our award-winning native museums and heritage centers and to experience our powwows and cultural events. (You can learn more about scheduled powwows at www.traveloregon.com/powwow.) We hope you’ll also take time to appreciate the natural wonders that make Oregon such an enchanting place to visit – the same mountains, coastline, rivers and valleys that have always provided for our people. Few places in the world offer such a diversity of landscapes, wildlife and culture within such a short drive. Many visitors may choose to visit all nine of Oregon’s federally recognized tribes. -

Growing up Indian: an Emic Perspective

GROWING UP INDIAN: AN EMIC PERSPECTIVE By GEORGE BUNDY WASSON, JR. A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Anthropology and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy june 2001 ii "Growing Up Indian: An Ernie Perspective," a dissertation prepared by George B. Wasson, Jr. in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Anthropology. This dissertation is approved and accepted by: Committee in charge: Dr. jon M. Erlandson, Chair Dr. C. Melvin Aikens Dr. Madonna L. Moss Dr. Rennard Strickland (outside member) Dr. Barre Toelken Accepted by: ------------------------------�------------------ Dean of the Graduate School iii Copyright 2001 George B. Wasson, Jr. iv An Abstract of the Dissertation of George Bundy Wasson, Jr. for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Anthropology to be taken June 2001 Title: GROWING UP INDIAN: AN EMIC PERSPECTN E Approved: My dissertation, GROWING UP INDIAN: AN EMIC PERSPECTN E describes the historical and contemporary experiences of the Coquille Indian Tribe and their close neighbors (as manifested in my own family), in relation to their shared cultures, languages, and spiritual practices. I relate various tribal reactions to the tragedy of cultural genocide as experienced by those indigenous groups within the "Black Hole" of Southwest Oregon. My desire is to provide an "inside" (ernie) perspective on the history and cultural changes of Southwest Oregon. I explain Native responses to living primarily in a non-Indian world, after the nearly total loss of aboriginal Coquelle culture and tribal identity through v decimation by disease, warfare, extermination, and cultural genocide through the educational policies of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, U.S. -

Download the Full Report 2007 5.Pdf PDF 1.8 MB

The Northwest Power and Conservation Council’s Directory of Columbia River Basin Tribes Council Document Number: 2007-05 Table of Contents I. Introduction 1 II. Tribes and Tribal Confederations 5 The Burns Paiute Tribe 7 The Coeur d’Alene Tribe 9 The Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Reservation 12 The Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation 15 The Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation 18 The Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community of Oregon 21 The Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation 23 The Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs Reservation of Oregon 25 The Kalispel Tribe of Indians 28 The Kootenai Tribe of Idaho 31 The Nez Perce Tribe 34 The Shoshone Bannock Tribes of the Fort Hall Reservation 37 The Shoshone-Paiute Tribes of the Duck Valley Reservation 40 The Spokane Tribe of Indians 42 III. Canadian First Nations 45 Canadian Columbia River Tribes (First Nations) 46 IV. Tribal Associations 51 Canadian Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fisheries Commission 52 Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission 53 Upper Columbia United Tribes 55 Upper Snake River Tribes 56 The Northwest Power and Conservation Council’s Tribal Directory i ii The Northwest Power and Conservation Council’s Tribal Directory Introduction The Northwest Power and Conservation Council’s Tribal Directory 1 2 The Northwest Power and Conservation Council’s Tribal Directory Introduction The Council assembled this directory to enhance our understanding and appreciation of the Columbia River Basin tribes, including the First Nations in the Canadian portion of the basin. The directory provides brief descriptions and histories of the tribes and tribal confedera- tions, contact information, and information about tribal fi sh and wildlife projects funded through the Council’s program. -

Reconstructing Proto-Sahaptian Sounds

Reconstructing Proto-Sahaptian Sounds Noel Rude Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation Sahaptin and the mutually unintelligible Nez Perce comprise the Sahaptian language family. This paper attempts to reconstruct the sound system of the parent language of that family. There is little dialect variation in the available data for Nez Perce, whereas Sahaptin divides into three definable dialect clusters: Columbia River (Umatilla, Tenino, Celilo, etc.); Northwest (Klickitat, Upper Cowlitz, Yakima, etc.); Northeast (Priest Rapids, Walla Walla, Palouse, etc.). Various features distinguish the dialects, e.g., long vowels derived from certain VCV sequences are more common in the Northern dialects and in Nez Perce, the Northeast dialects and Nez Perce are more likely to preserve the glottal stop, and the palatalization of *k is most extensive in the Columbia River dialects. The reconstructions proposed here are, as always, more or less tentative. Unless otherwise indicated the examples labeled Sahaptin (S) are from Umatilla.1 Figure 1. The Sahaptian language family Proto-Sahaptian Nez Perce Sahaptin Columbia River Northern Northwest Northeast 1 For the connection between Sahaptin and Nez Perce, see Aoki (1962), Rigsby (1965), Rigsby and Silverstein (1969), and Rude (1996, 2006). For the relationship with Plateau Penutian, see Aoki (1963), Rude (1987), and Pharis (2006). For a possible relationship within the broader Penutian macro-family, see DeLancey & Golla (1979) and Mithun (1999), also Rude (2000) for a possible connection with Uto-Aztecan. For Sahaptin grammars, see Jacobs (1931), Millstein (ca. 1990a), Rigsby and Rude (1996), Rude (2009), and for published NW Sahaptin texts, see Jacobs (1929, 1934, 1937). Beavert and Hargus (2010) provide a dictionary of Yakima Sahaptin, Millstein (ca.