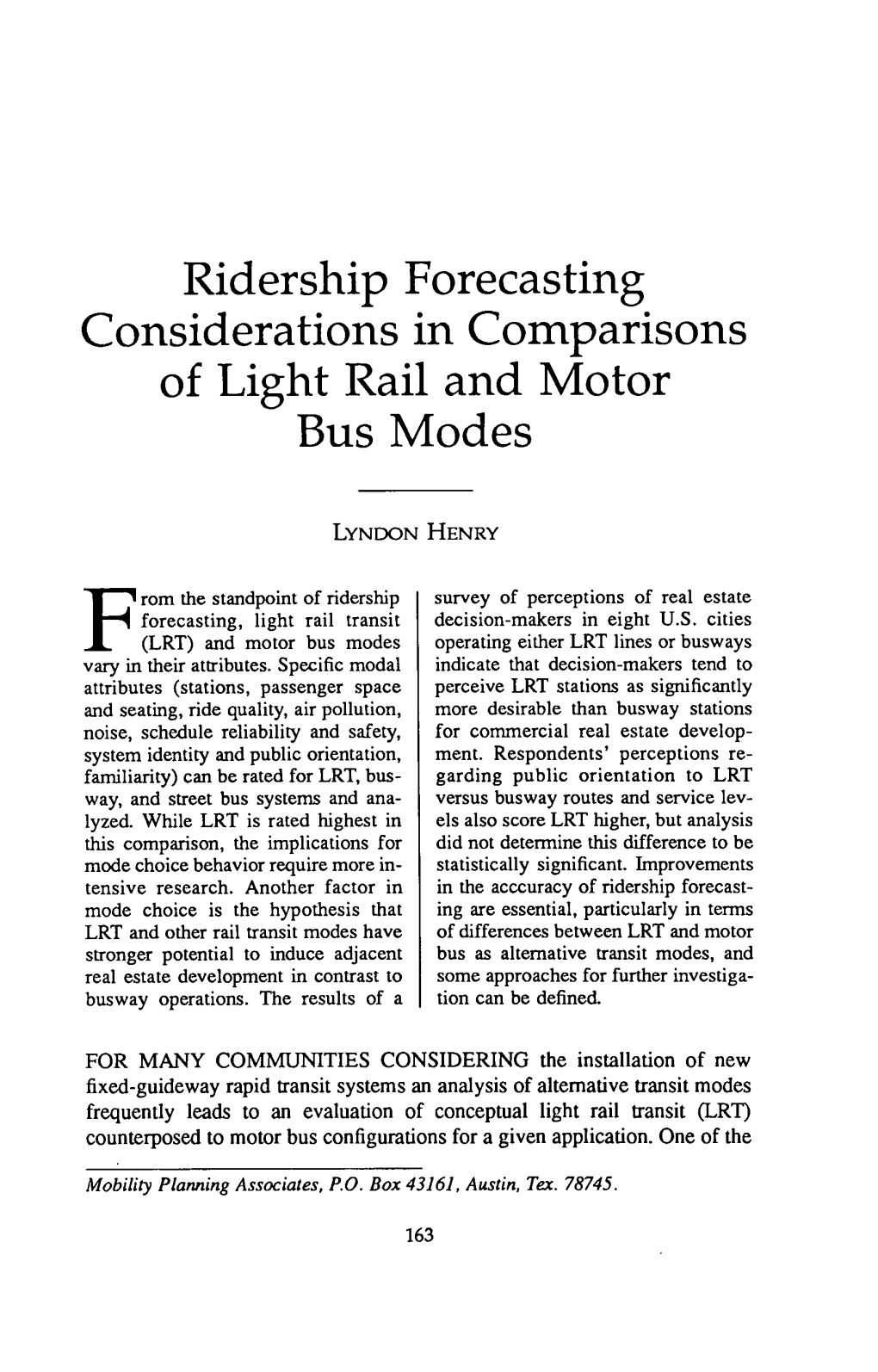

Ridership Forecasting Considerations in Comparisons of Light Ra Ii and Motor Bus Modes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proof of Payment Ordinance

Proof of Payment Ordinance BOARD OF DIRECTORS MEETING OCTOBER 26, 2017 What is Proof of Payment? 2 Proof of Payment means that passengers must present valid fare media, anywhere in the paid area of the system, upon request by authorized transit personnel. Why Proof of Payment 3 Estimated Revenue Annual Loss: $15M - $25M At least $6M loss supported by data Another $9M - $19M likely Currently, enforcement can only occur at “barrier” locations BPD must directly observe OR Employee or rider must: Witness and be willing to place offender under Citizens Arrest and BPD must be nearby and Offender must be contacted In short, without proof of payment, fare evaders are only concerned at the brief moments when they are sneaking in or out 3 Who Else Uses Proof of Payment? 4 California Other States SMART Dallas Area Rapid Transit Baltimore Light Rail San Francisco MTA Buffalo Metro Rail Santa Clara VTA Charlotte LYNX Cleveland Red Line Heavy Rail Sacramento RTA St. Louis Metro Link Seattle Sounder Commuter Rail and Central Los Angeles MTA Link Light Rail ACE Portland Tri-Met NJ Transit Hudson Bergen & River Lines Caltrain Houston Metro Rail San Diego Trolley Denver RTD Rail Who Uses BOTH Proof of Payment & Station Barriers? 5 SEPTA Philadelphia City Center stations Los Angeles MTA Purple and Red Lines Greater Cleveland RTA Red Line Montreal Metro BC Transit, Vancouver SkyTrain Proof of Payment Protocol 6 Inspections will be fair and non-biased. Police Officers and/or CSO’s will perform inspections within the paid area of the stations and on board non-crowded trains. -

Syracuse Transit System Analysis

Syracuse Transit System Analysis Prepared For: NYSDOT CENTRO Syracuse Metropolitan Transportation Council January 2014 The I‐81 Challenge Syracuse Transit System Analysis This report has been prepared for the New York State Department of Transportation by: Stantec Consulting Services, Inc. Prudent Engineering In coordination with: Central New York Regional Transportation Authority (CENTRO) Syracuse Metropolitan Transportation Council The I‐81 Challenge Executive Summary of the Syracuse Transit System Analysis I. Introduction The Syracuse Transit System Analysis (STSA) presents a summary of the methodology, evaluation, and recommendations that were developed for the transit system in the Syracuse metropolitan area. The recommendations included in this document will provide a public transit system plan that can be used as a basis for CENTRO to pursue state and federal funding sources for transit improvements. The study has been conducted with funding from the New York State Department of Transportation (NYSDOT) through The I‐81 Challenge study, with coordination from CENTRO, the Syracuse Metropolitan Transportation Council (SMTC), and through public outreach via The I‐81 Challenge public participation plan and Study Advisory Committee (SAC). The recommendations included in this system analysis are based on a combination of technical analyses (alternatives evaluation, regional modeling), public survey of current transit riders and non‐riders/former riders, meetings with key community representatives, and The I‐81 Challenge public workshops. The STSA is intended to serve as a long‐range vision that is consistent with the overall vision of the I‐81 corridor being developed as part of The I‐81 Challenge. The STSA will present a series of short‐term, mid‐term, and long‐ term recommendations detailing how the Syracuse metropolitan area’s transit system could be structured to meet identified needs in a cost‐effective manner. -

CITIZENS for REGIONAL TRANSIT NEWS Published by Citizens Regional Transit Corporation P.O

CITIZENS for REGIONAL TRANSIT NEWS published by Citizens Regional Transit Corporation P.O. Box 1186, Buffalo, NY 14231-1186 [email protected] http://citizenstransit.org/ Volume #7 Issue # 8 October 2006 Fatal Attraction ‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡‡ Admit it--an automobile is a beautiful thing. For many of us, the car may be CRTC Monthly Meeting the most beautiful, luxurious item we own. And for many people, their car is an emotional extension of themselves, as well as a cherished pesonal space. To purchase a car is to be attracted to a Tuesday, October 17 vehicle that promises much, including entry into the privilege of job access, 12:00 Noon opportunity for personal solitude on the highway and glimpses of glamour as the night-life crowd cruises the streets. “Eliminating the Theater Station??” But the very vehicle which sates our desires and provides access to many of our needs is fatal to our health. a discussion led by Nationally, car crashes accounted for 43,443 deaths in 2005.* At a rate of 14.6 Chris Hawley per 100,000 population, that’s about 146 fatalities in the Buffalo-Niagara region. Assistant Director, Furthermore, the miles traveled each year Campaign for Greater Buffalo Architecture, History is steadily rising, as is the numbers of vehicles on the road. and Culture Compounded with the effects of air pollution, our fascination with the The Final Design Report for the Preliminary Design of the “Cars Sharing Main automobile truly becomes a fatal Street” project has been posted by the City of Buffalo. In the report, the design attraction. team insists that the Theater Station should be eliminated in order to accommodate cars on Main Street in downtown Buffalo. -

Tip/Stip 2020-2024

2020 – 2024 Transportation Improvement Program (TIP) October 1, 2019 – September 30, 2024 This report was prepared with financial assistance of the U.S. Department of Transportation. However, the contents represent only the view of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the review or approval of the U.S. Department of Transportation. GBNRTC GBNRTC Policy Committee (Policy) Representatives Planning and Coordinating Committee (PCC) Representatives Member Agency Eligible Voting Representative Member Agency Eligible Voting Representative NYSDOT Planning & Program Manager NYSDOT Regional Director NFTA Manager, Grants and Government Affairs Planning & Program Manager Manager, Service Planning NFTA Executive Director Assistant Manager, Grants and Government Affairs Director, Public Transit NYSTA Manger of Permits and Traffic Manager, Grants and Government Affairs Division Director Manager, Service NYSTA Division Director Erie County Commissioner DPW Director of Engineering Erie County County Executive City of Buffalo Acting Commissioner DPW Commissioner DPW City Engineer Director of Engineering City of Buffalo Mayor Niagara County Commissioner DPW Deputy Comm. DPW Commissioner DPW Commissioner Economic Dev. City Engineer Niagara County County Legislature Chair City of Niagara Falls Director of Planning, Environment & Economic Development Senior Project Designer Commissioner Public Works City Engineer City of Niagara Falls Mayor Director of Planning, Environment & Economic Development Senior Project Designer 2020-2024 GBNRTC TIP - Page 2 -

An Evaluation of the University at Buffalo NFTA Transit Pass Program for Students, Faculty, and Staff Performing Organization: University at Buffalo, SUNY

front cover page.ai 1 8/12/2014 2:11:56 PM University Transportation Research Center - Region 2 Final Report Energy Savings from Transit Passes: An Evaluation of the University at Buffalo NFTA Transit Pass Program for Students, Faculty, and Staff Performing Organization: University at Buffalo, SUNY April 2014 Sponsor: University Transportation Research Center - Region 2 University Transportation Research Center - Region 2 Project No: 49997-29-24 The Region 2 University Transportation Research Center (UTRC) is one of ten original University Project Date: April 2014 Transportation Centers established in 1987 by the U.S. Congress. These Centers were established with the recognition that transportation plays a key role in the nation's economy and the quality of life of its citizens. University faculty members provide a critical link in resolving our national Project Title: Energy Savings from Transit Passes: An and regional transportation problems while training the professionals who address our transpor- Evaluation of the University at Buffalo NFTA Transit Pass tation systems and their customers on a daily basis. Program for Students, Faculty, and Staff The UTRC was established in order to support research, education and the transfer of technology Project’s Website: in the ield of transportation. The theme of the Center is "Planning and Managing Regional http://www.utrc2.org/research/projects/energy-savings- Transportation Systems in a Changing World." Presently, under the direction of Dr. Camille Kamga, transit-passes-evaluation the UTRC represents USDOT Region II, including New York, New Jersey, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Functioning as a consortium of twelve major Universities throughout the region, UTRC is located at the CUNY Institute for Transportation Systems at The City College of New York, Principal Investigator: the lead institution of the consortium. -

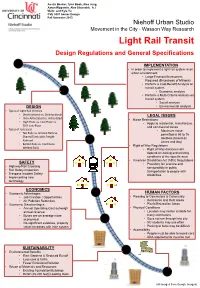

Light Rail Transit Design Regulations and General Specifications

Austin Becker, Tyler Book, Alex Jung, Aaron Rippstein, Alex Shumakh, A.J Wehr, and Kyle Yu CVE 5001 Senior Design Fall Semester 2013 Niehoff Urban Studio Movement in the City - Wasson Way Research Light Rail Transit Design Regulations and General Specifications IMPLEMENTATION • In order to implement a light rail system in an urban environment: • Large Financial Investment Required ($Hundreds of Millions) • Perform a Cost-Benefit Analysis on transit system • Economic analysis • Perform a Multi-Criteria Analysis on transit system • Social analysis DESIGN • Environmental analysis • Types of Light Rail Vehicles • Unidirectional vs. Bi-directional LEGAL ISSUES Non-Articulated vs. Articulated • • Noise Restrictions High Floor vs. Low Floor vs. • • Apply to residential, manufacture, 70% Low-Floor and commercial zones Types of rails used • • Maximum noise Tee Rails vs. Groove Rails vs. • permitted is 55 to 75 Shared Track with Freight decibels (based on Railroad zones and day) Bolted Rails vs. Continues • • Right of Way Regulations Welded Rails • Right of Way distances will depend on zoning and existing conditions of the specific area SAFETY • American Disabilities Act (ADA) Regulations • Providing fair practice and • Highway/Rail Crossing serviceability in public • Rail Safety Inspection transportation to people with • Trespass Incident Safety disabilities • Implementing new technology ECONOMICS • Economic Advantages: HUMAN FACTORS • Job Creation / Opportunities • Pleasing to Commuters & Community • Air Pollution Reduction • Restrooms and Rest -

Development of an Alternative Approach to Transit Demand Modeling

DEVELOPMENT OF AN ALTERNATIVE APPROACH TO TRANSIT DEMAND MODELING BY ILYA K. CHISTYAKOV THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Urban Planning in Urban Planning in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2017 Urbana, Illinois Master’s Committee: Associate Professor Arnab Chakraborty Associate Professor Bumsoo Lee ABSTRACT Development of transit systems around the nation faces limitations in funding and strict scrutiny of the proposed projects and their potential impact on urban environment. Potential ridership of the proposed transit route becomes one of the key indicators for analysis of investment projects. Transit demand depends on many multifaceted parameters affecting the mode choice of individual commuters. The urban planning as a field faces the demand in creation of a universal model which would allow to estimate transit demand of the areas of different scales and geographies, be simple to interpret and to replicate in any conditions. The research is discussing the process of development of a model able to predict potential transit demand under provision of a certain level of service based on the socio-economic parameters of the area within walking distance of a transit station. The modeling approach is based on the analysis of real transit ridership of rail stations in Chicago, Los Angeles, and Denver and the parameters possibly contributing to the number of passengers using them. The selection of the variables of the model was based on the most recent research in the field and relied on the multidimensional approach including regional and local scales of socio-economic and transit data. -

![(Niagara Frontier Transportation Authority 3/31/2020 [3/31/2020] (In](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3435/niagara-frontier-transportation-authority-3-31-2020-3-31-2020-in-5163435.webp)

(Niagara Frontier Transportation Authority 3/31/2020 [3/31/2020] (In

NIAGARA FRONTIER TRANSPORTATION AUTHORITY (A Component Unit of the State of New York) Management’s Discussion and Analysis For the Years Ended March 31, 2020, 2019, and 2018 (Unaudited) FACTORS IMPACTING THE AUTHORITY’S FUTURE Surface Transportation Approximately 25% of Metro’s revenues are derived from fare collection and advertising, while 75% are from outside government assistance. New York State is the Authority’s largest investor, historically providing almost 50% of total assistance while approximately 30% comes from local sources and approximately 20% from the federal government. Any changes in these funding sources can have a significant impact on Authority operations. COVID-19, and the related New York State stay-at-home order to prevent its spread, resulted in a 60-70% erosion in ridership at the end of fiscal 2020 and the beginning of fiscal 2021. It is anticipated that there will be a long-term impact on ridership even after the stay-at-home order is ultimately lifted. Additionally, to ensure that bus operators and passengers can maintain social distancing, Metro suspended fare collection beginning March 27, 2020. Fare collection will resume June 29, 2020 on all NFTA-Metro services. As part of Metro’s Blueprint for the Future, in addition to stabilizing government assistance, strategic plans concentrate on revenue generation, cost control, increasing organizational liquidity, technological improvements, operational changes such as implementation of a new fare box collection system, providing more flexible fare structures, improving service standards, continuing to engage the public with the Citizens Advisory Committee, Accessibility Advisory Committee, and workforce development. vii NIAGARA FRONTIER TRANSPORTATION AUTHORITY (A Component Unit of the State of New York) Management’s Discussion and Analysis For the Years Ended March 31, 2020, 2019, and 2018 (Unaudited) Metro-owned property along the Metro Rail corridor and property adjacent to Metro Rail has seen significant development in the recent years. -

Implementing Public Transportation in Utility Rights-Of-Way

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository Double Utility: Operating Public Transportation in Utility Rights-of-Way by Walker McGovney Freer A Masters Project submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of City and Regional Planning in the Department of City and Regional Planning Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: ______________________________________________________________________________ READER (optional) PRINT NAME ADVISOR SIGNATURE Double Utility: Operating Public Transportation in Utility Rights-of-Way Table of Contents Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Analysis of Existing Literature ................................................................................................................. 4 Research Methodology ............................................................................................................................. 6 Regulatory Framework and Governmental Oversight .................................................................................. 7 Transportation Environment ..................................................................................................................... 7 Federal Energy and Utility Framework ................................................................................................... -

July–December 2005 · $10.00 / Rails To

July–December 2005 · $10.00 / Rails to Rubber to Rails Again, Part 2 of 4: Nebraska–Pennsylvania Headlights The Magazine of Electric Railways Published since 1939 by the electric Railroaders’ Association, Inc. www.erausa.oRg staff Contents Editor and art Director July–December 2005 Sandy Campbell associate Editors Raymond R. Berger and John Pappas Contributors Andrew Grahl, Trevor Logan, Frank Pfuhler, Rails to Rubber to Rails Again edward Ridolph, John Stern and William Volkmer By Edward Ridolph. The street railway industry in the U.S. and Canada entered a precipitous 30-year decline after World War II. Under the banner of “light rail,” the industry was reborn in the early 1980s, a renaissance which continues to this day. Electric Railroaders’ Part two of Mr. Ridolph’s exhaustive 60-year retrospective looks at U.S. systems Association, Inc. E from Nebraska to Pennsylvania. Board of Directors 2010 To the right, Liberty Valley Transit’s famed 1030 “Liberty Bell Limited” travels along President the side of U.S. Highway 202 in true interurban fashion between Allentown and the Frank S. Miklos Philadelphia suburb of Norristown in the late 1940s. Allentown, Pa.’s summary First Vice President William K. Guild begins on page 54. John stern phoTo second Vice President & Corresponding secretary Raymond R. Berger on the cover, Pittsburgh Railways Company PCC 1483 on the 98-Glassport line Third Vice President & Recording secretary passes McKeesport B&o station in May 1961. The Pittsburgh, Pa. summary begins Robert J. Newhouser on page 66. ray BergeR phoTo Treasurer Michael Glikin Director John Pappas Membership secretary Sandy Campbell officers 2010 Trip & Convention Chairman Jack May Librarian William K. -

The Hiawatha Line: Minnesota

Report #2 in the series Transitway Impacts Research Program Sponsors: Anoka County Center for Transportation Studies, University of The Hiawatha Line: Minnesota Hennepin County Impacts on Land Use and Residential Housing Value Itasca Group Metropolitan Council Minnesota Department of Transportation Ramsey County University Metropolitan Consortium, University of Minnesota Washington County In cooperation with: Center for Urban and Regional Affairs, University of Minnesota City of Minneapolis City of Saint Paul Dakota County Federal Transit Administration State and Local Policy Program, Hubert H. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs, University of Minnesota CTS Report 10-04 Technical Report Documentation Page 1. Report No. 2. 3. Recipients Accession No. CTS 10-04 4. Title and Subtitle 5. Report Date February 2010 The Hiawatha Line: Impacts on Land Use and Residential 6. Housing Value 7. Author(s) 8. Performing Organization Report No. Edward G. Goetz, Kate Ko, Aaron Hagar, Hoang Ton, Jeff Matson 9. Performing Organization Name and Address 10. Project/Task/Work Unit No. Humphrey Institute of Public Affairs CTS Project # 2008067 301-19th Avenue South 11. Contract (C) or Grant (G) No. Minneapolis, MN 12. Sponsoring Organization Name and Address 13. Type of Report and Period Covered Hennepin County, Anoka County, Ramsey County, Washington Final Report County, Itasca Group, Metropolitan Council, 14. Sponsoring Agency Code University Metropolitan Consortium, Center for Transportation Studies, Minnesota Department of Transportation 15. Supplementary Notes http://www.cts.umn.edu/Publications/ResearchReports/ 16. Abstract (Limit: 250 words) This report presents the results of an examination of the economic and land-use impacts of the Hiawatha Light Rail Line. Specifically, the report contains findings on the impact of the line on residential property values, housing investment, and land-use patterns. -

Australia Light Rail Report.Pdf

Light Railrail in In Australia Australia Light rail – the time has come! 1 Light Rail in Australia Australia has a mixed record with electrified transport systems, This document sketches a vision for the future of Australian with many extensive pre-war systems torn out in the early cities as we move into an era where climate change, petrol post-war years. Only Melbourne’s system remains at scale, with prices and traffic congestion demand that we rethink the way dramatically reduced services in Adelaide and Sydney, while our cities works. Perth, Hobart and Brisbane no longer operate services at all. Regional centres including Kalgoorlie, Bendigo, Ballarat and We can prosper in a carbon-light future if we make decisions Leonora boasted systems dating back to the gold rush years. now to shock-proof ourselves against the challenges of the 21st century, and a rapid, electrified mass transit system must be a With peak oil, climate change and traffic congestion all calling part of this vision. into question post-war transport planning, it is time to reinvent the age of electrified mass transit. Light rail is a form of urban rail public transport, essentially a modern tram system, using electric railcars large enough to accommodate up to 60 people as well as wheelchairs and bicycles. Light rail infrastructure has a low impact on the Melbourne urban environment, with rails unobtrusively laid along existing roadways or road reserves and stops along median strips. Melbourne was the only Australian city to retain its pre-war tram network. Today it is the largest network in the world, with 501 vehicles on 249 kilometres of double track.