The Hiawatha Line: Minnesota

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

To Become a Human Being the Message of Tadodaho Chief Leon Shenandoah 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

TO BECOME A HUMAN BEING THE MESSAGE OF TADODAHO CHIEF LEON SHENANDOAH 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Leon Shenandoah | 9781571743411 | | | | | To Become a Human Being The Message of Tadodaho Chief Leon Shenandoah 1st edition PDF Book Hidden categories: All articles with unsourced statements Articles with unsourced statements from May Perhaps one of the most profound books I have ever read. The memory of our circles in the early mornings as we gathered to give Thanksgiving to brother Sun is a sacred seed that sits in our minds, with the sacred fire in our hearts. He gave us a good mind to think clearly. Search Search for:. Then our Hopi brothers from the south would give their thanks to brother sun. With the Good Mind, our circles, councils, and ceremonies create healing through disciplining our minds for life around us. Every year, we gathered in a place where there was a need to strengthen traditional Native culture and restore balance on respected Native territory. The Native American way of life has kept its people close to their living roots. Our elders taught us all natural life is a part of the Native way of life, and this is how our children learn from the old ones how to keep happy, healthy, and feeling strong with the life around them in harmony. Sort order. Nobody else does either. Leon was also a leader of the Onondaga Nation. We are all the Creator's people. Download as PDF Printable version. Friend Reviews. Read more More Details Sam rated it it was amazing Jan 04, I say they can find their ceremony if they use the good mind. -

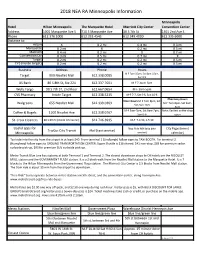

2018 NEA RA Minneapolis Information

2018 NEA RA Minneapolis Information Minneapolis Hotel Hilton Minneapolis The Marquette Hotel Marriott City Center Convention Center Address 1001 Marquette Ave S 710 S Marquette Ave 30 S 7th St 1301 2nd Ave S Phone 612.376.1000 612.333.4545 612.349.4000 612.335.6000 Distance to: Hilton X 0.2 mi 0.4 mi 0.3 mi Marquette 0.2 mi X 0.2 mi 0.5 mi Marriott 0.4 mi 0.2 mi X 0.7 mi Convention Ctr 0.3 mi 0.5 mi 0.7 mi X Target 0.2 mi 0.2 mi 0.2 mi 0.5 mi CVS (inside target) 0.2 mi 0.2 mi 0.2 mi 0.5 mi Business Address Phone Hours M-F 7am-10pm, Sat 8am-10pm, Target 900 Nicollet Mall 612.338.0085 Sun 9-9 US Bank 80 S 8th St, Ste 224 612.337.7051 M-F 7:30am-5pm Wells Fargo 90 S 7th ST, 2nd floor 612.667.0654 M-F 9am-5pm CVS Pharmacy Inside Target 612.338.5215 M-F 7-7, Sat 9-6, Sun 10-6 Pharmacy Hours Store Hours M-F 7am-8pm, Sat Walgreens 655 Nicollet Mall 612.339.0363 M-F 7am-6pm, Sat 9am- 9-6, Sun 10-5 5pm M-F 5am-7pm, Sat 6am-7pm, Note: Earliest coffee shop Coffee & Bagels 1100 Nicollet Ave 612.338.0767 Sun 6-6 open St. Croix Cleaners 80 S 8th St (Inside IDS Center) 612.746.3935 M-F 7-1:30, 2-5:30 Useful apps for Nice Ride MN (city bike City Pages (event TripGo: City Transit iHail (taxi service) Minneapolis: service) calendar) Taxi ride into the city from the airport is at least $40. -

2019 Annual Regional Park-And-Ride System

2019 ANNUAL REGIONAL PARK & RIDE SYSTEM REPORT JANUARY 2020 Prepared for: Metropolitan Council Metro Transit Minnesota Valley Transit Authority SouthWest Transit Maple Grove Transit Plymouth Metrolink Northstar Link Minnesota Department of Transportation Prepared by: Ari Del Rosario Metro Transit Engineering and Facilities, Planning and Urban Design Table of Contents Overview ......................................................................................................................................................3 Capacity Changes........................................................................................................................................6 System Capacity and Usage by Travel Corridor .........................................................................................7 Planned Capacity Expansion .......................................................................................................................8 About the System Survey ............................................................................................................................9 Appendix A: Facility Utilization Data .......................................................................................................10 Park & Ride System Data .....................................................................................................................10 Park & Pool System Data .....................................................................................................................14 Bike & Ride -

Minnesota Statewide Freight System Plan Task 5 Strategies and Implementation

Minnesota Statewide Freight System Plan Task 5 Strategies and Implementation draft report prepared for Minnesota Department of Transportation prepared by Cambridge Systematics, Inc. with SRF Consulting Group, Inc. KimleyHorn and Associates, Inc. Leo Penne Consulting September 2015 www.camsys.com draft Minnesota Statewide Freight System Plan Task 5 Strategies and Implementation prepared for Minnesota Department of Transportation prepared by Cambridge Systematics, Inc. 100 CambridgePark Drive, Suite 400 Cambridge, MA 02140 with SRF Consulting Group, Inc. KimleyHorn and Associates, Inc. Leo Penne Consulting date September 2015 Minnesota Statewide Freight System Plan Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction .........................................................................................................11 2.0 Freight System Investments..............................................................................21 2.1 About Freight Projects ...............................................................................21 2.2 Highway System Investments ..................................................................22 2.3 NonHighway System Investments .......................................................212 2.4 Freight Project Types for MnDOT’s Future Support...........................215 3.0 Supporting Strategies ........................................................................................31 3.1 Accountability, Transparency and Communication..............................36 3.2 Transportation in Context .......................................................................311 -

H. Con. Res. 442

IV 108TH CONGRESS 2D SESSION H. CON. RES. 442 Recognizing the 75th anniversary of Amtrak’s Empire Builder rail line. IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES JUNE 3, 2004 Ms. MCCOLLUM submitted the following concurrent resolution; which was referred to the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure CONCURRENT RESOLUTION Recognizing the 75th anniversary of Amtrak’s Empire Builder rail line. Whereas on June 11, 1929, the Great Northern Railroad’s premier passenger train, the Empire Builder, began oper- ating between Chicago, Illinois, and Seattle, Washington; Whereas prominent Minnesotan and Great Northern’s found- er, James J. Hill, himself known as the Empire Builder, once said of his railroad ‘‘When we are all dead and gone, the sun will shine, the rain will fall, and the rail- road will run as usual’’; Whereas the Empire Builder, now operated by Amtrak, today travels between Seattle, Washington, or Portland, Or- egon, and Chicago, Illinois, by way of Spokane, Wash- ington, and St. Paul and Minneapolis, Minnesota; 2 Whereas the Empire Builder serves 45 stations, including two in Illinois, six in Wisconsin, six in Minnesota, seven in North Dakota, twelve in Montana, one in Idaho, ten in Washington, and one in Oregon; Whereas over 415,000 people rode the Empire Builder last year; Whereas nearly 3,000 people work for Amtrak in Empire Builder States; Whereas Amtrak expended over $103,000,000 in goods and services in Empire Builder States in fiscal year 2003; Whereas the Empire Builder follows the trail of Lewis and Clark’s historic expedition west through the Louisiana Territory; Whereas the Empire Builder provides grand views of our country’s natural heritage, such as the Mississippi River, the North Dakota plains, Big Sky country in Montana, the Columbia River gorge, the Cascade Mountains, and Puget Sound; and Whereas the Empire Builder takes passengers to the Sears Tower, the Wisconsin Dells, the St. -

Transportation on the Minneapolis Riverfront

RAPIDS, REINS, RAILS: TRANSPORTATION ON THE MINNEAPOLIS RIVERFRONT Mississippi River near Stone Arch Bridge, July 1, 1925 Minnesota Historical Society Collections Prepared by Prepared for The Saint Anthony Falls Marjorie Pearson, Ph.D. Heritage Board Principal Investigator Minnesota Historical Society Penny A. Petersen 704 South Second Street Researcher Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401 Hess, Roise and Company 100 North First Street Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401 May 2009 612-338-1987 Table of Contents PROJECT BACKGROUND AND METHODOLOGY ................................................................................. 1 RAPID, REINS, RAILS: A SUMMARY OF RIVERFRONT TRANSPORTATION ......................................... 3 THE RAPIDS: WATER TRANSPORTATION BY SAINT ANTHONY FALLS .............................................. 8 THE REINS: ANIMAL-POWERED TRANSPORTATION BY SAINT ANTHONY FALLS ............................ 25 THE RAILS: RAILROADS BY SAINT ANTHONY FALLS ..................................................................... 42 The Early Period of Railroads—1850 to 1880 ......................................................................... 42 The First Railroad: the Saint Paul and Pacific ...................................................................... 44 Minnesota Central, later the Chicago, Milwaukee and Saint Paul Railroad (CM and StP), also called The Milwaukee Road .......................................................................................... 55 Minneapolis and Saint Louis Railway ................................................................................. -

Indigenous People of Western New York

FACT SHEET / FEBRUARY 2018 Indigenous People of Western New York Kristin Szczepaniec Territorial Acknowledgement In keeping with regional protocol, I would like to start by acknowledging the traditional territory of the Haudenosaunee and by honoring the sovereignty of the Six Nations–the Mohawk, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida, Seneca and Tuscarora–and their land where we are situated and where the majority of this work took place. In this acknowledgement, we hope to demonstrate respect for the treaties that were made on these territories and remorse for the harms and mistakes of the far and recent past; and we pledge to work toward partnership with a spirit of reconciliation and collaboration. Introduction This fact sheet summarizes some of the available history of Indigenous people of North America date their history on the land as “since Indigenous people in what is time immemorial”; some archeologists say that a 12,000 year-old history on now known as Western New this continent is a close estimate.1 Today, the U.S. federal government York and provides information recognizes over 567 American Indian and Alaskan Native tribes and villages on the contemporary state of with 6.7 million people who identify as American Indian or Alaskan, alone Haudenosaunee communities. or combined.2 Intended to shed light on an often overlooked history, it The land that is now known as New York State has a rich history of First includes demographic, Nations people, many of whom continue to influence and play key roles in economic, and health data on shaping the region. This fact sheet offers information about Native people in Indigenous people in Western Western New York from the far and recent past through 2018. -

Airport Survey Report Final

Minneapolis - St. Paul Airport Special Generator Survey Metropolitan Council Travel Behavior Inventory Final report prepared for Metropolitan Council prepared by Cambridge Systematics, Inc. April 17, 2012 www.camsys.com report Minneapolis - St. Paul Airport Special Generator Survey Metropolitan Council Travel Behavior Inventory prepared for Metropolitan Council prepared by Cambridge Systematics, Inc. 115 South LaSalle Street, Suite 2200 Chicago, IL 60603 date April 17, 2012 Minneapolis - St. Paul Airport Special Generator Survey Table of Contents 1.0 Background ...................................................................................................... 1-1 2.0 Survey Implementation ................................................................................. 2-1 2.1 Sampling Plan ......................................................................................... 2-1 2.2 Survey Effort ........................................................................................... 2-2 2.3 Questionnaire Design ............................................................................. 2-2 2.4 Field Implementation ............................................................................. 2-3 3.0 Data Preparation for Survey Expansion ....................................................... 3-1 3.1 Existing Airline Databases ..................................................................... 3-1 3.2 Airport Survey Database - Airlines ....................................................... 3-2 3.3 Airport Survey Database -

CVE and Constitutionality in the Twin Cities: How Countering Violent Extremism Threatens the Equal Protection Rights of American Muslims in Minneapolis-St

American University Law Review Volume 69 Issue 6 Article 6 2020 CVE and Constitutionality in the Twin Cities: How Countering Violent Extremism Threatens the Equal Protection Rights of American Muslims in Minneapolis-St. Paul Sarah Chaney Reichenbach American University Washington College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aulr Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Constitutional Law Commons, Law and Politics Commons, Law and Society Commons, President/Executive Department Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation Reichenbach, Sarah Chaney (2020) "CVE and Constitutionality in the Twin Cities: How Countering Violent Extremism Threatens the Equal Protection Rights of American Muslims in Minneapolis-St. Paul," American University Law Review: Vol. 69 : Iss. 6 , Article 6. Available at: https://digitalcommons.wcl.american.edu/aulr/vol69/iss6/6 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington College of Law Journals & Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in American University Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ American University Washington College of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CVE and Constitutionality in the Twin Cities: How Countering Violent Extremism Threatens the Equal Protection Rights of American Muslims in Minneapolis-St. Paul Abstract In 2011, President Barack Obama announced a national strategy for countering violent extremism (CVE) to attempt to prevent the “radicalization” of potential violent extremists. The Obama Administration intended the strategy to employ a community-based approach, bringing together the government, law enforcement, and local communities for CVE efforts. -

Maple Grove Transit 2016 “Expressbusservice”

Maple Grove Transit 2016 “Express Bus Service” Customer Survey Report of Results December 2016 Prepared by: 2955 Valmont Road • Suite 300 • Boulder, Colorado 80301 • t: 303-444-7863 • www.n-r-c.com Maple Grove Transit “Express Bus Service” Customer Survey December 2016 Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... 1 Survey Background ...................................................................................................................4 Survey Results ...........................................................................................................................4 Appendix A: Verbatim Responses to Open-ended Survey Questions .................................... 34 Appendix B: Select Results Compared by Respondent Race/Ethnicity .................................. 92 Appendix C: Copy of Survey Questionnaire .......................................................................... 107 National Research Center, Inc. Report of Results Prepared by Maple Grove Transit “Express Bus Service” Customer Survey December 2016 List of Tables Table 1: Question 1................................................................................................................................................ 4 Table 2: Question 2 ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Table 3: Question 3 Compared by Question 1 .................................................................................................... -

Proof of Payment Ordinance

Proof of Payment Ordinance BOARD OF DIRECTORS MEETING OCTOBER 26, 2017 What is Proof of Payment? 2 Proof of Payment means that passengers must present valid fare media, anywhere in the paid area of the system, upon request by authorized transit personnel. Why Proof of Payment 3 Estimated Revenue Annual Loss: $15M - $25M At least $6M loss supported by data Another $9M - $19M likely Currently, enforcement can only occur at “barrier” locations BPD must directly observe OR Employee or rider must: Witness and be willing to place offender under Citizens Arrest and BPD must be nearby and Offender must be contacted In short, without proof of payment, fare evaders are only concerned at the brief moments when they are sneaking in or out 3 Who Else Uses Proof of Payment? 4 California Other States SMART Dallas Area Rapid Transit Baltimore Light Rail San Francisco MTA Buffalo Metro Rail Santa Clara VTA Charlotte LYNX Cleveland Red Line Heavy Rail Sacramento RTA St. Louis Metro Link Seattle Sounder Commuter Rail and Central Los Angeles MTA Link Light Rail ACE Portland Tri-Met NJ Transit Hudson Bergen & River Lines Caltrain Houston Metro Rail San Diego Trolley Denver RTD Rail Who Uses BOTH Proof of Payment & Station Barriers? 5 SEPTA Philadelphia City Center stations Los Angeles MTA Purple and Red Lines Greater Cleveland RTA Red Line Montreal Metro BC Transit, Vancouver SkyTrain Proof of Payment Protocol 6 Inspections will be fair and non-biased. Police Officers and/or CSO’s will perform inspections within the paid area of the stations and on board non-crowded trains. -

Llght Rall Translt Statlon Deslgn Guldellnes

PORT AUTHORITY OF ALLEGHENY COUNTY LIGHT RAIL TRANSIT V.4.0 7/20/18 STATION DESIGN GUIDELINES ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Port Authority of Allegheny County (PAAC) provides public transportation throughout Pittsburgh and Allegheny County. The Authority’s 2,600 employees operate, maintain, and support bus, light rail, incline, and paratransit services for approximately 200,000 daily riders. Port Authority is currently focused on enacting several improvements to make service more efficient and easier to use. Numerous projects are either underway or in the planning stages, including implementation of smart card technology, real-time vehicle tracking, and on-street bus rapid transit. Port Authority is governed by an 11-member Board of Directors – unpaid volunteers who are appointed by the Allegheny County Executive, leaders from both parties in the Pennsylvania House of Representatives and Senate, and the Governor of Pennsylvania. The Board holds monthly public meetings. Port Authority’s budget is funded by fare and advertising revenue, along with money from county, state, and federal sources. The Authority’s finances and operations are audited on a regular basis, both internally and by external agencies. Port Authority began serving the community in March 1964. The Authority was created in 1959 when the Pennsylvania Legislature authorized the consolidation of 33 private transit carriers, many of which were failing financially. The consolidation included the Pittsburgh Railways Company, along with 32 independent bus and inclined plane companies. By combining fare structures and centralizing operations, Port Authority established the first unified transit system in Allegheny County. Participants Port Authority of Allegheny County would like to thank agency partners for supporting the Light Rail Transportation Station Guidelines, as well as those who participated by dedicating their time and expertise.