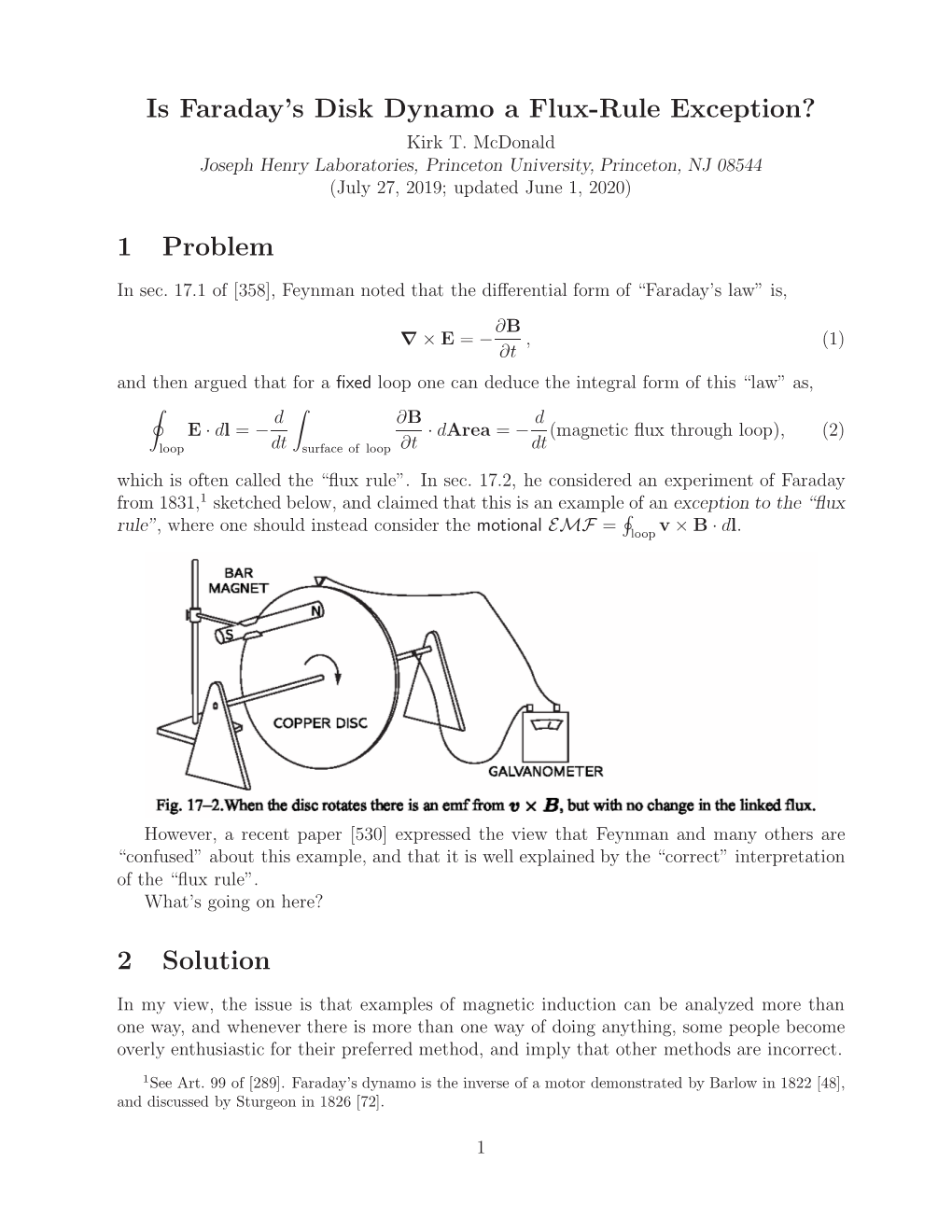

Is Faraday's Disk Dynamo a Flux-Rule

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modelling and Simulation of a Simple Homopolar Motor of Faraday's Type

FACTA UNIVERSITATIS (NIS)ˇ SER.: ELEC. ENERG. vol. 24, no. 2, August 2011, 221-242 Modelling and Simulation of a Simple Homopolar Motor of Faraday's Type Dedicated to Professor Slavoljub Aleksic´ on the occasion of his 60th birthday Hartmut Brauer, Marek Ziolkowski, Konstantin Porzig, and Hannes Toepfer Abstract: During the application of simulation tools of computational electromag- netics it is sometimes difficult to decide whether the problems can be solved by the computation of electromagnetic fields or circuit simulation tools have to be applied ad- ditionally. The paper describes a typical situation in an electromagnetic CAD course, not only for beginners. The modelling and numerical simulation of a simple homopo- lar motor, similar to that what has been presented by Michael Faraday in 1821 firstly, was used as an example. To simulate the current flow in the permanent magnet the FEM software codes COMSOL Multiphysics including the integrated SPICE module and MAXWELL have been used. The correct simulation of the entire electric circuit as well as the precise modelling of the impressed current and of the electrode contacts turned out to be very important. Keywords: Homopolar motor; homopolar generator; Faraday’s motor principle; FEM software. 1 Introduction S is so often the case with invention, the credit for development of the elec- A tric motor is belongs to more than one individual. It was through a process of development and discovery beginning with Hans Christian Oersted’s discovery of electromagnetism in 1820 and involving additional work by William Sturgeon, Manuscript received on June 8. 2011. The authors are with Ilmenau University of Technology, Faculty of Electrical Engineer- ing and Information Technology, Dept. -

Resolution of the Faraday Paradox

Resolution of the Faraday Paradox Sokolov Gennady, Babin Walter, Chubukin Anatoly, Sokolov Vitaly, Loydap Valery More than 150 years ago, Michael Faraday discovered that in a unipolar generator with a simultaneous rotation of a magnet and a disk, a voltmeter in a fixed measuring circuit shows an EMF. The question arose whether the field rotates with the magnet or remains stationary. Numerous researchers are still unsuccessfully trying to answer this question, and it is generally accepted that direct measurement of emf is impossible. Einstein begins the article “On the Electrodynamics of Moving Bodies” with the statement that “the electrodynamic interaction between a magnet and a conductor with current ... depends only on the relative motion of the conductor and magnet” [1] Supporters of the SRT still claim that unipolar induction is a relativistic Effect. This paper presents the results of our study of the Faraday paradox. It is shown that conventional measurement methods in principle do not allow to experimentally solve the problem of field rotation. The method of measuring the emf we developed, allowed us to prove that the rotation of the magnet is not equivalent to the rotation of the conductor around the magnet, while simultaneously rotating the disk and the magnet, the field does not rotate and EMF is induced only in the disk. Essence of the Faraday Paradox The Faraday paradox arose from the fact that conventional measuring devices do not allow us to determine where the emf is induced in the disk of a unipolar generator or in a measuring circuit. The problem is that to measure the induced emf, a voltmeter is connected to the disk with two wires, as a result of which the rotating disk and the fixed wires form a closed loop in which the same emf is induced both in case the field rotates and in case the field is stationary. -

Physics Celebrity

Born 22 September 1791 Newington Butts, Surrey, England Died 25 August 1867 (aged 75) Hampton Court, Surrey, England Residence: England Fields Physics and Chemistry Known for Faraday's law of induction, Electrochemistry, Faraday effect, Faraday cage, Faraday constant, Faraday cup Faraday's laws of electrolysis, Faraday paradox, Faraday rotator Faraday-efficiency effect, Faraday wave, Faraday wheel, Lines of force Influenced by: Humphry Davy , William Thomas Brande Notable awards Royal Medal (1835 & 1846) Religious stance Sandemanian Michael Faraday was an English chemist and physicist (or natural philosopher, in the terminology of the time) who contributed to the fields of electromagnetism and electrochemistry. Faraday studied the magnetic field around a conductor carrying a DC electric current, and established the basis for the magnetic field concept in physics. He discovered electromagnetic induction, diamagnetism, and laws of electrolysis. He established that magnetism could affect rays of light and that there was an underlying relationship between the two phenomena. His inventions of electromagnetic rotary devices formed the foundation of electric motor technology, and it was largely due to his efforts that electricity became viable for use in technology. As a chemist, Faraday discovered benzene, investigated the clathrate hydrate of chlorine, invented an early form of the bunsen burner and the system of oxidation numbers, and popularized terminology such as anode, cathode, electrode, and ion. Although Faraday received little formal education and knew little of higher mathematics, such as calculus, he was one of the most influential scientists in history. Some historians of science refer to him as the best experimentalist in the history of science. -

The Faraday Paradox Experiment

THE FARADAY PARADOX EXPERIMENT Duncan G. Cumming, Ph.D. (Camb.) Feb 28, 2018 1 OBJECTIVE To investigate the emf produced by a disc rotating in front of a bar magnet, as a function of rotation of the magnet itself and routing of the brush connecting wires. INTRODUCTION Michael Faraday did a series of experiments in 1851 where he rotated a disc in front of a bar magnet, and found that it produced an emf because of the motion of a conductor in a magnetic field. Paradoxically, he found that the same emf was produced even if the magnet and the disc were fastened together and co‐rotated. He explained this by saying that the magnetic field should be regarded as being “fixed in space”, notwithstanding the rotation of the magnet itself. Faraday did not report any effects based on the precise routing of the wire connecting the pick‐up brush to the galvanometer, presumably because he did not observe any such effects. In 1998 a paper was published by A.G. Kelly1, where he reported no effect from re‐routing the pickup wire when the magnet was stationary. However, he reported a substantial effect when using a co‐ rotating magnet. In fact, by careful routing of the wire, he was able to reduce the emf to zero within the accuracy of his galvanometer. Such a finding would have some very profound implications. Two different emfs from the same brush could be used to drive a current through a load, even though the brush itself were removed from the experiment. This would lead to a brushless homopolar machine, a device of substantial commercial value. -

The Relativistic Electrodynamics Turbine. Experimentum Crucis of New Induction Law

The Relativistic Electrodynamics Turbine. Experimentum Crucis of New Induction Law. Albert Serra1, ∗, Carles Paul2, ∗ ,Ramón Serra3, ∗ 1Departamento de Física, Facultad de Ciencias, Universidad de los Andes, Venezuela. 2Departamento de Mecatrónica, Sección de Física, ESUP, 08302, Mataró, España. 3Innovem, Tecnocampus TCM2, 08302, Mataró, España. ABSTRACT Easy experiments carried out in the dawn of electromagnetism are still being a reason for scientific articles, because its functioning contradicts some laws and rules of electromagnetic theory. Although these experiments led Einstein to discover the relativistic electrodynamics and explained its working, the scientific community had not understood this. They see in these experiments a proof against relativity and prefer to look for the solution in the electromagnetics’ theory or accept that their are an exception. By means of a long and detailed experimental study with a new design in electromagnetic engines and improvements of these experiments that we call relativistic electrodynamics turbine, we managed to explain its working using relativistic electrodynamics. The revision of these experiments had taken us to discover the real law of induction, which does not have any exceptions. The explanation of the relativistic electrodynamics turbine led us to discard the Faraday induction law and argue that the true law of induction is a consequence of the conservation of the angular momentum of the charges as the conservation of the angular momentum of the mass. Thus Einstein’s idea to unify electromagnetism and mechanics is now clear and also opens the way for new research in science. ∗ Albert Serra Valls. Tel.: +34-638-922-843; e-mail: [email protected] ∗ Carles Paul Recarens. -

The Construction of the Pure Homopolar Generator Reveals Physical Problem of Maxwell’S Equations

The construction of the Pure homopolar generator reveals physical problem of Maxwell’s equations. Pavol Ivana1,2,*, Ivan Vlcek2, and Marika Ivanova3 1Supratech s.r.o. scientific-technical laboratory, Mokra 314, Zlin, 76001, Czech Republic 21. Internetova Komercni, spol. s r.o., SNP 1178, Otrokovice, 76502, Czech Republic 3University of Bergen Faculty of Mathematics and Natural Sciences, PO Box 7803, Bergen, 5020, Norway *[email protected] ABSTRAKT In this article, we present a part of the research results during 2012-2015, which shows that there must exist another description of Faraday’s homopolar generator than the generally acknowledged one. For example, as a device that simulates necessary and sufficient condition for induction. This paper presents the experimental pure homopolar generator (PHG, defined as a generator that does not need any brushes, electronics or semiconductor to ensure the generation of direct current) as a proof that the movement of an electrically neutral conductor in homogeneous circles of magnetic field does not induce any voltage. It is happening in spite of all physical/technological alterations for the sake of theoretical functionality. In the experiment described here, these theoretical requirements are achieved through an effective shielding by high-temperature superconductors. The reason for this negative result may be the fact that PHG only complies the necessary but not sufficient condition. In contrast, the relativistic explanation of Faraday homopolar generator (hereinafter referred to as FHG) seems to be misleading and unrealistic in the context of the article on the experiment described. If we still insisted on the correctness of Maxwell’s concept, we would have to admit that the heterogenous field can be shielded from a perspective of any outer system of reference, but such a system of reference for homogenous circles of magnetic field would not exist. -

The Homopolar Generator: an Analytical Example

The homopolar generator: an analytical example Hendrik van Hees August 7, 2014 1 Introduction It is surprising that the homopolar generator, invented in one of Faraday’s ingenious experiments in 1831, still seems to create confusion in the teaching of classical electrodynamics. This is the more surprising as the problem of the “electromagnetism of moving bodies” has been solved more than 100 years ago by Einstein in his famous paper, introducing his Special Theory of relativity (1905), and mathematically consolidated by Minkowski hin his famous talk on space and time (1908). Also one can still find some misleading, if not even wrong, statements on the issue in the more re- cent literature, and I could not find any paper using the local (differential) Maxwell equations and the Lorentz-force Law which is always valid, as suggested in the Feynman Lectures (vol. II) in connection ~ ~ ~ with the use of Faraday’s flux law (the integral form of one of the Maxwell equations, E = @t B=c, see App. A). r× − Here, I try to provide precisely such a study for the most simple arrangement showing the effects, namely the rotating homogeneously magnetized sphere. 2 The one-piece Faraday generator It is surprising that the so-called Faraday paradox is still a source of confusion although the “electrody- namics of moving bodies” is well understood with Einstein’s famous special-relativity paper. Here, I try to give an explanation by avoiding the use of the integral form of Maxwell’s equation, which seems to be the main source of the confusion. I’ll comment on this in Appendix A. -

Modeling of Aqueous Corrosion

This article was originally published in Shreir’s Corrosion, published by Elsevier. The attached copy is provided by Elsevier for the author’s benefit and for the benefit of the author’s institution. It may be used for non-commercial research and educational use, including (without limitation) use in instruction at your institution, distribution to specific colleagues who you know, and providing a copy to your institution’s administrator. All other uses, reproduction and distribution, including (without limitation) commercial reprints, selling or licensing of copies or access, or posting on open internet sites, personal or institution websites or repositories, are prohibited. For exception, permission may be sought for such use through Elsevier’s permissions site at: http://www.elsevier.com/locate/permissionusematerial Anderko A 2010 Modeling of Aqueous Corrosion. In: Richardson J A et al. (eds.) Shreir’s Corrosion, volume 2, pp. 1585-1629 Amsterdam: Elsevier. Author's personal copy 2.38 Modeling of Aqueous Corrosion A. Anderko OLI Systems Inc., 108 American Road, Morris Plains, NJ 07950, USA ß 2010 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved. 2.38.1 Introduction 1586 2.38.2 Thermodynamic Modeling of Aqueous Corrosion 1587 2.38.2.1 Computation of Standard-State Chemical Potentials 1588 2.38.2.2 Computation of Activity Coefficients 1588 2.38.2.3 Electrochemical Stability Diagrams 1591 2.38.2.3.1 Diagrams at elevated temperatures 1594 2.38.2.3.2 Effect of multiple active species 1594 2.38.2.3.3 Diagrams for nonideal solutions 1595 2.38.2.3.4 Diagrams -

Electrostatic Application Principles

International PhD Seminar on Computational electromagnetics and optimization in electrical engineering – CEMOEE 2010 10-13 September, Sofia, Bulgaria ELECTROSTATIC APPLICATION PRINCIPLES invited paper Mićo GAĆANOVIĆ "Jede Ursache hat ihre Wirkung; jede Wirkung ihre Ursache; an explanation of ultimate substance, change, and the exis- alles geschieht gesetzmäßig, Zufall ist nur ein Name für ein tence of the world -- without reference to mythology. Those unbekanntes Gesetz. Es gibt viele Ebenen der Ursächlichkeit, aber philosophers were also influential, and eventually Thales' nichts entgeht dem Gesetz." rejection of mythological explanations became an essential “Kybalion” idea for the scientific revolution. He was also the first to define general principles and set forth hypotheses, and as a result has been dubbed the "Father of Science". HISTORY In mathematics, Thales used geometry to solve prob- lems such as calculating the height of pyramids and the Thales of Miletus Thales of Miletus (Θαλῆς ὁ distance of ships from the shore. He is credited with the Μιλήσιος) Born ca. 624–625 BC Died ca. 547–546 BC , first use of deductive reasoning applied to geometry, by [16]. deriving four corollaries to Thales' Theorem. As a result, he As reported by the Ancient Greek philosopher Thales of has been hailed as the first true mathematician and is the Miletus around 600 B.C.E., charge (or electricity) could be first known individual to whom a mathematical discovery accumulated by rubbing fur on various substances, such as has been attributed. amber. The Greeks noted that the charged amber buttons In 1600, the English scientist William Gilbert returned could attract light objects such as hair. -

Electric Energy from Physical Vacuum Space

Electric Energy from Physical Vacuum Space Kiyoung Kim1 Abstract The law of conservation of energy, one of the first principles in physics, has been believed without a doubt; thus, it is natural that all scientific paradigms also have been built on the basis of the first principle. However, it is true that the first principle is based on empiricism, saying that any violation of energy conservation has not been observed or confirmed in objectivity. Meanwhile, there have been many pioneering researches for free electric energy generation challenging for the first principle although none of them has been acknowledged openly in public yet. However, in the new paradigm of physics including ontological reality in 4-D complex space, the free electric energy generation is explained how it is possible and why the conventional energy conservation law is not valid. 1 [email protected] Introduction As we have believed in the law of conservation of energy like a religious doctrine, we have believed that all physical interactions occur only in phenomenological world. However, the ontological reality of physical vacuum and its interactions with physical phenomena has been hypothesized with 4-D complex space introduced as physical space, in which the physical vacuum in the physical space, which has been considered as just empty space in conventional scientific consensus, is completely filled with vacuum particles, those of which interact with physical objects in phenomena; physical interactions, such as gravitational interaction, electric interaction, magnetic interaction, or electromagnetic interaction, can be explained uniquely with the first principle in the physical space. (Kim 1997, 2008, 2017) Now, we can understand physical interactions, more than ever, not just conceptual meanings based on phenomenology but fundamental mechanisms in new paradigm of physics as above. -

The Faraday's Paradox

The Faraday's Paradox Yun, Ji-Won and Lee, Dongsub [email protected] [email protected] Key Points of the Faraday paradox • The electromotive force(emf) is induced not because flux passing thru the given circuit is changing in time, but there is the Lorentz force exerted on the charge carriers. • Electromagnetic field can change when the frame is changed. Furthermore, moving magnetic field can be seen as an electric field in some other frame and vice versa. • Even though the Lorentz forces exerted on each charge carriers inside the circuit are non-trivial, whether there is a current or not depends on the net Lorentz force integrated along the wire and even it does not have to be closed circuit. • To determine whether there is non-zero emf or not, a good check point is to consider the work done on the system. If there was a work done on it, there might be emf, but if there is not, there never be non-zero net emf. The reason why the Faraday paradox arose lies on the insensitiveness on both the relativity and existence of the electron. Basically the electromagnetism already has relativistic structure. Thus, we have to be careful on the change of frames and to use covariant coordinate change rather than simple Galilean coordinate transform. Then no matter what frame we use to investigate the system, we will reach to the same answer. Besides, original description of Faraday on the induction states about the emf focuses on the induced current rather than each electrons. -

Unipolar Induction a Messy Corner of Electromagnetism: a Contribution for the Clean up with Some Far-Reaching Consequences

European J of Physics Education Volume 11 Issue 1 1309-7202 Härtel Unipolar Induction A Messy Corner of Electromagnetism: A Contribution for The Clean Up with Some Far-Reaching Consequences Hermann Härtel ITAP –Institute for Theoretical Physics and Astrophysics University of Kiel (Received 16.11.2019, Accepted 16.01.2020) Abstract In the light of own measurements on a Faraday generator, the well-known theories concerning Unipolar Induction and the Faraday paradox seem to be problematic. On the other hand, all results obtained, and all other processes described as a paradox in connection with the Faraday generator can be explained without contradiction based on the theory of Wilhelm Weber. Keywords: Faraday generator, Unipolar induction, Ampère´s law, Weber's Fundamental Law of Electrodynamics HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT In 1832 Faraday discovered that one could induce a DC voltage with a rotating magnet but realized at the same time that a rotating magnet behaves strangely in comparison to a linearly moving permanent magnet, a fact initially incomprehensible to him. It made no difference whether the permanent magnet rotates about the same axis of symmetry together with a rotating disc, or whether the magnet remains at rest. In both cases, Faraday observed an induction effect. If one uses a magnet made of conductive material and dispenses with the possibility of letting the disc rotate independently, the independent disc can be omitted. Thus, there are the following two versions of a so-called Faraday generator (Figure 1), both used by Faraday. There are different explanations about how this generator operates since the times of Faraday.