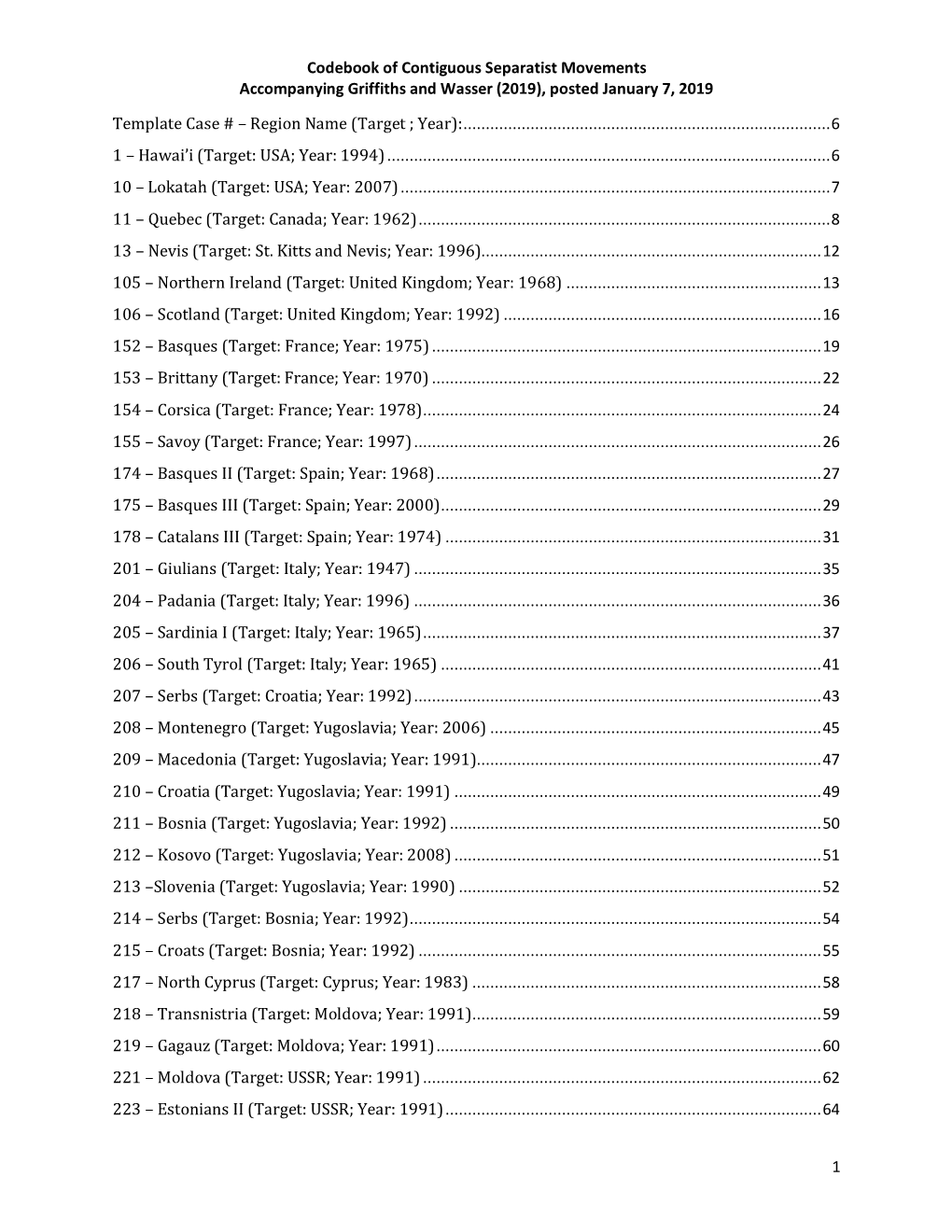

Codebook of Contiguous Separatist Movements Accompanying Griffiths and Wasser (2019), Posted January 7, 2019

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Clash of Thoughts Within the Arab Discourse

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2009 The Clash Of Thoughts Within The Arab Discourse Chadia Louai University of Central Florida Part of the Political Science Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Louai, Chadia, "The Clash Of Thoughts Within The Arab Discourse" (2009). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 4114. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/4114 CLASH OF THOUGHTS WITHIN THE CONTEMPORARY ARAB DISCOURSE By CHADIA LOUAI L.D. University Hassan II, 1992 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts In the department of Political Science In the College of Sciences At the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Fall Term 2009 Major Professor: Houman A. Sadri ©2009 Chadia Louai ii ABSTRACT The Clash of Civilization thesis by Samuel Huntington and the claims of other scholars such as Bernard Lewis reinforced the impression in the West that the Arab world is a homogeneous and rigid entity ready to clash with other civilizations. In fact, some in the West argue that world civilizations have religious characteristics, for that reason the fundamental source of conflict in this new world will be primarily cultural and religious. However, other scholars argue that there is no single Islamic culture but rather multiple types of political Islam and different perception of it. -

Thesis Rests with Its Author

University of Bath PHD Identity in a post-communist Balkan state: A study in north Albania Saltmarshe, Douglas Award date: 1999 Awarding institution: University of Bath Link to publication Alternative formats If you require this document in an alternative format, please contact: [email protected] General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 09. Oct. 2021 IDENTITY IN A POST-COMMUNIST BALKAN STATE: A STUDY IN NORTH ALBANIA Submitted by Douglas Saltmarshe for the degree of PhD of the University of Bath 1999 COPYRIGHT Attention is drawn to the fact that copyright of this thesis rests with its author. This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that everyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the prior consent of its author. -

Defense Security Cooperation University Expert Course of Instruction

Defense Security Cooperation University Expert Course of Instruction Content, Design, Implementation JEFFERSON P. MARQUIS, JENNIFER D. P. MORONEY, PAULINE MOORE, REBECCA HERMAN, JONATHAN WELCH, REID DICKERSON Prepared for the Office of the Secretary of Defense Approved for public release NATIONAL DEFENSE RESEARCH INSTITUTE For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RRA572-1 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2020 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface In its 2017 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA), the U.S. Con- gress called for the professionalization of the security cooperation (SC) workforce as part of a range of reforms designed to confront perceived deficiencies in Department of Defense (DoD) SC planning, man- agement, execution, and assessment and placed the Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA) in charge of this effort. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-49128-0 — Democracy and Nationalism in Southeast Asia Jacques Bertrand Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-49128-0 — Democracy and Nationalism in Southeast Asia Jacques Bertrand Index More Information Index 1995 Mining Law, 191 Authoritarianism, 4, 11–13, 47, 64, 230–31, 1996 Agreement (with MNLF), 21, 155–56, 232, 239–40, 245 157–59, 160, 162, 165–66 Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao, 142, 150, 153, 157, 158–61, 167–68 Abu Sayaff, 14, 163, 170 Autonomy, 4, 12, 25, 57, 240 Accelerated development unit for Papua and Aceh, 20, 72, 83, 95, 102–3, 107–9 West Papua provinces, 131 Cordillera, 21, 175, 182, 186, 197–98, 200 Accommodation. See Concessions federalism, 37 Aceh Peace Reintegration Agency, 99–100 fiscal resources, 37 Aceh Referendum Information Centre, 82, 84 fiscal resources, Aceh, 74, 85, 89, 95, 98, Aceh-Nias Rehabilitation and Reconstruction 101, 103, 105 Agency, 98 fiscal resources, Cordillera, 199 Act of Free Choice, 113, 117, 119–20, 137 fiscal resources, Mindanao, 150, 156, 160 Administrative Order Number 2 (Cordillera), fiscal resources, Papua, 111, 126, 128 189–90, See also Ancestral domain Indonesia, 88 Al Hamid, Thaha, 136 jurisdiction, 37 Al Qaeda, 14, 165, 171, 247 jurisdiction, Aceh, 101 Alua, Agus, 132, 134–36 jurisdiction, Cordillera, 186 Ancestral Domain, 166, 167–70, 182, 187, jurisdiction, Mindanao, 167, 169, 171 190, 201 jurisdiction, Papua, 126 Ancestral Land, 184–85, 189–94, 196 Malay-Muslims, 22, 203, 207, 219, 224 Aquino, Benigno Jr., 143, 162, 169, 172, Mindanao, 20, 146, 149, 151, 158, 166, 172 197, 199 Papua, 20, 122, 130 Aquino, Butz, 183 territorial, 27 Aquino, Corazon. See Aquino, Cory See also Self-determination Aquino, Cory, 17, 142–43, 148–51, 152, Azawad Popular Movement, Popular 180, 231 Liberation Front of Azawad (FPLA), 246 Armed Forces, 16–17, 49–50, 59, 67, 233, 236 Badan Reintegrasi Aceh. -

Pashtunistan: Pakistan's Shifting Strategy

AFGHANISTAN PAKISTAN PASHTUN ETHNIC GROUP PASHTUNISTAN: P AKISTAN ’ S S HIFTING S TRATEGY ? Knowledge Through Understanding Cultures TRIBAL ANALYSIS CENTER May 2012 Pashtunistan: Pakistan’s Shifting Strategy? P ASHTUNISTAN : P AKISTAN ’ S S HIFTING S TRATEGY ? Knowledge Through Understanding Cultures TRIBAL ANALYSIS CENTER About Tribal Analysis Center Tribal Analysis Center, 6610-M Mooretown Road, Box 159. Williamsburg, VA, 23188 Pashtunistan: Pakistan’s Shifting Strategy? Pashtunistan: Pakistan’s Shifting Strategy? The Pashtun tribes have yearned for a “tribal homeland” in a manner much like the Kurds in Iraq, Turkey, and Iran. And as in those coun- tries, the creation of a new national entity would have a destabilizing impact on the countries from which territory would be drawn. In the case of Pashtunistan, the previous Afghan governments have used this desire for a national homeland as a political instrument against Pakistan. Here again, a border drawn by colonial authorities – the Durand Line – divided the world’s largest tribe, the Pashtuns, into two the complexity of separate nation-states, Afghanistan and Pakistan, where they compete with other ethnic groups for primacy. Afghanistan’s governments have not recog- nized the incorporation of many Pashtun areas into Pakistan, particularly Waziristan, and only Pakistan originally stood to lose territory through the creation of the new entity, Pashtunistan. This is the foundation of Pakistan’s policies toward Afghanistan and the reason Pakistan’s politicians and PASHTUNISTAN military developed a strategy intended to split the Pashtuns into opposing groups and have maintained this approach to the Pashtunistan problem for decades. Pakistan’s Pashtuns may be attempting to maneuver the whole country in an entirely new direction and in the process gain primacy within the country’s most powerful constituency, the military. -

Trends in Conflict and Stability in the Indo-Pacific

Emerging Issues Report Trends in conflict and stability in the Indo-Pacific Iffat Idris GSDRC, University of Birmingham January 2021 About this report The K4D Emerging Issues report series highlights research and emerging evidence to policy-makers to help inform policies that are more resilient to the future. K4D staff researchers work with thematic experts and FCDO to identify where new or emerging research can inform and influence policy. This report is based on ten days of desk-based research carried out in December 2020. K4D services are provided by a consortium of leading organisations working in international development, led by the Institute of Development Studies (IDS), with the Education Development Trust, Itad, University of Leeds Nuffield Centre for International Health and Development, Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM), University of Birmingham International Development Department (IDD) and the University of Manchester Humanitarian and Conflict Response Institute (HCRI). For any enquiries, please contact [email protected]. Suggested citation Idris, I. (2020). Trends in conflict and stability in the Indo-Pacific. K4D Emerging Issues Report 42. Brighton, UK: Institute of Development Studies. DOI: 10.19088/K4D.2021.009 Copyright This report was prepared for the UK Government’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) and its partners in support of pro-poor programmes. Except where otherwise stated, it is licensed for non- commercial purposes under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0. K4D cannot be held responsible for errors or any consequences arising from the use of information contained in this report. Any views and opinions expressed do not necessarily reflect those of FCDO, K4D or any other contributing organisation. -

Download File

Italy and the Sanusiyya: Negotiating Authority in Colonial Libya, 1911-1931 Eileen Ryan Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 ©2012 Eileen Ryan All rights reserved ABSTRACT Italy and the Sanusiyya: Negotiating Authority in Colonial Libya, 1911-1931 By Eileen Ryan In the first decade of their occupation of the former Ottoman territories of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica in current-day Libya, the Italian colonial administration established a system of indirect rule in the Cyrenaican town of Ajedabiya under the leadership of Idris al-Sanusi, a leading member of the Sufi order of the Sanusiyya and later the first monarch of the independent Kingdom of Libya after the Second World War. Post-colonial historiography of modern Libya depicted the Sanusiyya as nationalist leaders of an anti-colonial rebellion as a source of legitimacy for the Sanusi monarchy. Since Qaddafi’s revolutionary coup in 1969, the Sanusiyya all but disappeared from Libyan historiography as a generation of scholars, eager to fill in the gaps left by the previous myopic focus on Sanusi elites, looked for alternative narratives of resistance to the Italian occupation and alternative origins for the Libyan nation in its colonial and pre-colonial past. Their work contributed to a wider variety of perspectives in our understanding of Libya’s modern history, but the persistent focus on histories of resistance to the Italian occupation has missed an opportunity to explore the ways in which the Italian colonial framework shaped the development of a religious and political authority in Cyrenaica with lasting implications for the Libyan nation. -

Dod OIG Semiannual Report to the Congress October 1, 2012 Through

DoD IG Semiannual Report to the Congress -October 1, 2012 - March 31, 2013 - March 31, to Semiannual Report the 2012 Congress IG -October 1, DoD United States Department of Defense OCTOBERInspector 1, 2012 TO MARCH General 31, 2013 Semiannual Report to the Congress Required by Public Law 95-452 InteGrIty effIcIency accountabIlIty excellence InteGrIty effIcIency accountabIlIty excellence Mission Our mission is to provide independent, relevant, and timely over- sight of the Department that: supports the warfighter; promotes accountability, integrity, and efficiency; advises the Secretary of Defense and Congress; and informs the public. Vision Our vision is to be a model oversight organization in the federal government by leading change, speaking truth, and promoting ex- cellence; a diverse organization, working together as one profes- sional team, recognized as leaders in our field. Fraud, Waste and Abuse HOTLINE 1.800.424.9098 • www.dodig.mil/hotline For more information about whistleblower protection, please see the inside back cover. INSPECTOR GENERAL DEPARTMENT OF DEFENSE 4800 MARK CENTER DRIVE ALEXANDRIA, VIRGINIA 22350-1500 I am pleased to present the Department of Defense Inspector General Semiannual Report to Congress for the reporting period October 1, 2012, through March 31, 2013, issued in accordance with the Inspector General Act of 1978, as amended. This year marks the 30th anniversary of DoD IG. Over the course of 30 years, many groundbreak- ing audits, inspections, and investigations have paved the way for reducing fraud, waste, and abuse across the Department. When you consider the projects we have completed over the past 30 years, the positive impact we have made on the Department is truly remarkable. -

Rediscovering the Arab Dimension of Middle East Regional Politics

Review of International Studies page 1 of 22 2011 British International Studies Association doi:10.1017/S0260210511000283 The New Arab Cold War: rediscovering the Arab dimension of Middle East regional politics MORTEN VALBJØRN AND ANDRÉ BANK* Abstract. This article provides a conceptual lens for and a thick interpretation of the emergent regional constellation in the Middle East in the first decade of the 21st century. It starts out by challenging two prevalent claims about regional politics in the context of the 2006 Lebanon and 2008–09 Gaza Wars: Firstly, that regional politics is marked by a fundamental break from the ‘old Middle East’ and secondly, that it has become ‘post-Arab’ in the sense that Arab politics has ceased being distinctly Arab. Against this background, the article develops the understanding of a New Arab Cold War which accentuates the still important, but widely neglected Arab dimension in regional politics. By rediscovering the Arab Cold War of the 1950–60s and by drawing attention to the transformation of Arab nationalism and the importance of new trans-Arab media, the New Arab Cold War perspective aims at supplementing rather that supplanting the prominent moderate-radical, sectarian and Realist-Westphalian narratives. By highlighting dimensions of both continuity and change it does moreover provide some critical nuances to the frequent claims about the ‘newness’ of the ‘New Middle East’. In addition to this more Middle East-specific contribution, the article carries lessons for a number of more general debates in International Relations theory concerning the importance of (Arab-Islamist) non-state actors and competing identities in regional politics as well as the interplay between different forms of sovereignty. -

University Students' Perceptions on Inter-Ethnic Unity Among

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by UKM Journal Article Repository Jurnal Komunikasi Malaysian Journal of Communication Jilid 34(4) 2018: 134-153 University Students’ Perceptions on Inter-ethnic Unity among Malaysians: Situational Recognition, Social Self-Construal and Situational Complexity ARINA ANIS AZLAN CHANG PENG KEE Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia MOHD YUSOF ABDULLAH International University of Malaya-Wales, Kuala Lumpur ABSTRACT National unity is pertinent to the stability and progress of a country. For multi-ethnic nations such as Malaysia, diversity is perceived as a challenge to national unity. Extant literature shows that the different ethnic groups in Malaysia have expressed different ideals on inter-ethnic unity and differ in their ideas on how it may be achieved. To what extent do these differences exist? The purpose of this research was to investigate the perceptions of inter-ethnic unity in Malaysia among the three main ethnic groups. A survey measuring perceptions on the issue of inter-ethnic unity was distributed among 575 university students at four different institutions of higher learning in the Klang Valley, Malaysia. The results show that the different ethnic groups held similar problem perceptions in terms of problem recognition, involvement, constraint recognition, and did not differ significantly in terms of their social position on the problem. There were however, significant differences between the Chinese and Malay/Bumiputeras, as well as between the Chinese and Indians when it came to perceived level of knowledge and experience about the problem. The findings indicate that different ethnic groups may be differently equipped to handle the issue of inter-ethnic unity in Malaysia. -

Download Download

Nisan / The Levantine Review Volume 4 Number 2 (Winter 2015) Identity and Peoples in History Speculating on Ancient Mediterranean Mysteries Mordechai Nisan* We are familiar with a philo-Semitic disposition characterizing a number of communities, including Phoenicians/Lebanese, Kabyles/Berbers, and Ismailis/Druze, raising the question of a historical foundation binding them all together. The ethnic threads began in the Galilee and Mount Lebanon and later conceivably wound themselves back there in the persona of Al-Muwahiddun [Unitarian] Druze. While DNA testing is a fascinating methodology to verify the similarity or identity of a shared gene pool among ostensibly disparate peoples, we will primarily pursue our inquiry using conventional historical materials, without however—at the end—avoiding the clues offered by modern science. Our thesis seeks to substantiate an intuition, a reading of the contours of tales emanating from the eastern Mediterranean basin, the Levantine area, to Africa and Egypt, and returning to Israel and Lebanon. The story unfolds with ancient biblical tribes of Israel in the north of their country mixing with, or becoming Lebanese Phoenicians, travelling to North Africa—Tunisia, Algeria, and Libya in particular— assimilating among Kabyle Berbers, later fusing with Shi’a Ismailis in the Maghreb, who would then migrate to Egypt, and during the Fatimid period evolve as the Druze. The latter would later flee Egypt and return to Lebanon—the place where their (biological) ancestors had once dwelt. The original core group was composed of Hebrews/Jews, toward whom various communities evince affinity and identity today with the Jewish people and the state of Israel. -

The Case of Somalia (1960-2001)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) State collapse and post-conflict development in Africa : the case of Somalia (1960-2001) Mohamoud, A. Publication date 2002 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Mohamoud, A. (2002). State collapse and post-conflict development in Africa : the case of Somalia (1960-2001). Thela Thesis. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:28 Sep 2021 Chapterr four Thee Pitfalls of Colonialism and Public Pursuit 4.1.. Introduction Thiss chapter traces how the change brought about by the colonial imposition led to the primacyy of the public pursuit in Somali politics over a century. The colonial occupation of Somaliaa not only transformed the political economy of Somali society as transformationists emphasizee but also split the Somali people and their territories.74 Therefore, as I will argue in thiss study, the multiple partitioning of the country is one of the key determinants that fundamentallyy account for the destructive turn of events in Somalia at present.