Introduction: Some Significances of the Two Cultures Debate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Edward M. Eyring

The Chemistry Department 1946-2000 Written by: Edward M. Eyring Assisted by: April K. Heiselt & Kelly Erickson Henry Eyring and the Birth of a Graduate Program In January 1946, Dr. A. Ray Olpin, a physicist, took command of the University of Utah. He recruited a number of senior people to his administration who also became faculty members in various academic departments. Two of these administrators were chemists: Henry Eyring, a professor at Princeton University, and Carl J. Christensen, a research scientist at Bell Laboratories. In the year 2000, the Chemistry Department attempts to hire a distinguished senior faculty member by inviting him or her to teach a short course for several weeks as a visiting professor. The distinguished visitor gets the opportunity to become acquainted with the department and some of the aspects of Utah (skiing, national parks, geodes, etc.) and the faculty discover whether the visitor is someone they can live with. The hiring of Henry Eyring did not fit this mold because he was sought first and foremost to beef up the graduate program for the entire University rather than just to be a faculty member in the Chemistry Department. Had the Chemistry Department refused to accept Henry Eyring as a full professor, he probably would have been accepted by the Metallurgy Department, where he had a courtesy faculty appointment for many years. Sometime in early 1946, President Olpin visited Princeton, NJ, and offered Henry a position as the Dean of the Graduate School at the University of Utah. Henry was in his scientific heyday having published two influential textbooks (Samuel Glasstone, Keith J. -

The Two Cultures of Undergraduate Academic Engagement

Res High Educ DOI 10.1007/s11162-008-9090-y The Two Cultures of Undergraduate Academic Engagement Steven Brint Æ Allison M. Cantwell Æ Robert A. Hanneman Received: 11 June 2007 Ó Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2008 Abstract Using data on upper-division students in the University of California system, we show that two distinct cultures of engagement exist on campus. The culture of engagement in the arts, humanities and social sciences focuses on interaction, participation, and interest in ideas. The culture of engagement in the natural sciences and engineering focuses on improvement of quantitative skills through collaborative study with an eye to rewards in the labor market. The two cultures of engagement are strongly associated with post-graduate degree plans. The findings raise questions about normative conceptions of good educational practices in so far as they are considered to be equally relevant to students in all higher education institutions and all major fields of study. Keywords Academic engagement Á Student cultures Á Research universities Á Graduate degree aspirations Considerable scholarly and policy attention has been directed toward the improvement of undergraduate education for more than two decades (see, e.g., AAC 1985; Chickering and Gamson 1987). Yet interest appears to have peaked in recent years, as indicated by large- scale improvement efforts at many of the country’s leading research universities (see, e.g., Rimer 2007). The most important cause of this heightened interest is the report of the Secretary of Education’s Commission on the Future of Higher Education (also known as the Spellings Commission). The Spellings Commission proposed incentives for the adoption of stan- dardized testing for purposes of making higher education accountable to consumers. -

Cambridge's 92 Nobel Prize Winners Part 2 - 1951 to 1974: from Crick and Watson to Dorothy Hodgkin

Cambridge's 92 Nobel Prize winners part 2 - 1951 to 1974: from Crick and Watson to Dorothy Hodgkin By Cambridge News | Posted: January 18, 2016 By Adam Care The News has been rounding up all of Cambridge's 92 Nobel Laureates, celebrating over 100 years of scientific and social innovation. ADVERTISING In this installment we move from 1951 to 1974, a period which saw a host of dramatic breakthroughs, in biology, atomic science, the discovery of pulsars and theories of global trade. It's also a period which saw The Eagle pub come to national prominence and the appearance of the first female name in Cambridge University's long Nobel history. The Gender Pay Gap Sale! Shop Online to get 13.9% off From 8 - 11 March, get 13.9% off 1,000s of items, it highlights the pay gap between men & women in the UK. Shop the Gender Pay Gap Sale – now. Promoted by Oxfam 1. 1951 Ernest Walton, Trinity College: Nobel Prize in Physics, for using accelerated particles to study atomic nuclei 2. 1951 John Cockcroft, St John's / Churchill Colleges: Nobel Prize in Physics, for using accelerated particles to study atomic nuclei Walton and Cockcroft shared the 1951 physics prize after they famously 'split the atom' in Cambridge 1932, ushering in the nuclear age with their particle accelerator, the Cockcroft-Walton generator. In later years Walton returned to his native Ireland, as a fellow of Trinity College Dublin, while in 1951 Cockcroft became the first master of Churchill College, where he died 16 years later. 3. 1952 Archer Martin, Peterhouse: Nobel Prize in Chemistry, for developing partition chromatography 4. -

The “Two Cultures” in Clinical Psychology: Constructing Disciplinary Divides in the Management of Mental Retardation

The “Two Cultures” in Clinical Psychology: Constructing Disciplinary Divides in the Management of Mental Retardation Andrew J. Hogan Creighton University Isis, Vol. 109, no. 4 (2018): 695-719 In a 1984 article, psychologist Gregory Kimble lamented what he saw as the two distinct cultures of his discipline. Writing in American Psychologist, a prominent professional journal, he noted, “In psychology, these conflicting cultures [scientific and humanistic] exist within a single field, and those who hold opposing values are currently engaged in a bitter family feud.” 1 In making his argument, Kimble explicitly drew upon British scientist and novelist C.P. Snow’s 1959 lecture The Two Cultures, in which Snow expressed concern about a lack of intellectual engagement between scientists and humanists, and about the dominant position of the humanities in British education and culture. Kimble used Snow’s critique to help make sense of what he perceived to be a similar polarizing divide between “scientific” and “humanistic” psychologists. 2 As Kimble described it, humanistic psychologists differed form their scientific colleagues in placing their ambitions to enact certain social policies and to promote particular social values- based ideologies ahead of the need for the scientific validation of these approaches. Kimble demonstrated his purported two cultures divide in psychology using survey data he collected from 164 American Psychological Association (APA) members. Each was part of either APA Division 3 (Experimental Psychology) or one of three other Divisions, which represented special interest groups within the psychology field. His results, illustrated on a spectrum from scientific to humanistic orientation, showed a purported divide between experimental psychologists on the scientific side, and their humanistic colleagues in the other three Divisions (See Figures 1,2). -

Third Wave of Science Studies: Studies of Expertise and Experience H.M

Social Studies of Science http://sss.sagepub.com/ The Third Wave of Science Studies: Studies of Expertise and Experience H.M. Collins and Robert Evans Social Studies of Science 2002 32: 235 DOI: 10.1177/0306312702032002003 The online version of this article can be found at: http://sss.sagepub.com/content/32/2/235 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Social Studies of Science can be found at: Email Alerts: http://sss.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://sss.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav >> Version of Record - Apr 1, 2002 What is This? Downloaded from sss.sagepub.com at UNIV OF RHODE ISLAND LIBRARY on December 9, 2013 DISCUSSION PAPER ABSTRACT Science studies has shown us why science and technology cannot always solve technical problems in the public domain. In particular, the speed of political decision-making is faster than the speed of scientific consensus formation. A predominant motif over recent years has been the need to extend the domain of technical decision-making beyond the technically qualified ´elite, so as to enhance political legitimacy. We argue, however, that the ‘Problem of Legitimacy’ has been replaced by the ‘Problem of Extension’ – that is, by a tendency to dissolve the boundary between experts and the public so that there are no longer any grounds for limiting the indefinite extension of technical decision-making rights. We argue that a Third Wave of Science Studies – Studies of Expertise and Experience (SEE) – is needed to solve the Problem of Extension. -

1 Ethers, Religion and Politics In

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE Ethers, religion and politics in late-Victorian physics: beyond the Wynne thesis AUTHORS Noakes, Richard JOURNAL History of Science DEPOSITED IN ORE 16 June 2008 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10036/30065 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication ETHERS, RELIGION AND POLITICS IN LATE-VICTORIAN PHYSICS: BEYOND THE WYNNE THESIS RICHARD NOAKES 1. INTRODUCTION In the past thirty years historians have demonstrated that the ether of physics was one of the most flexible of all concepts in the natural sciences. Cantor and Hodge’s seminal collection of essays of 1981 showed how during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries British and European natural philosophers invented a range of ethers to fulfil diverse functions from the chemical and physiological to the physical and theological.1 In religious discourse, for example, Cantor identified “animate” and spiritual ethers invented by neo-Platonists, mystics and some Anglicans to provide a mechanism for supporting their belief in Divine immanence in the cosmos; material, mechanistic and contact-action ethers which appealed to atheists and Low Churchmen because such media enabled activity in the universe without constant and direct Divine intervention; and semi-spiritual/semi-material ethers that appealed to dualists seeking a mechanism for understanding the interaction of mind and matter. 2 The third type proved especially attractive to Oliver Lodge and several other late-Victorian physicists who claimed that the extraordinary physical properties of the ether made it a possible mediator between matter and spirit, and a weapon in their fight against materialistic conceptions of the cosmos. -

Download Report 2010-12

RESEARCH REPORt 2010—2012 MAX-PLANCK-INSTITUT FÜR WISSENSCHAFTSGESCHICHTE Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Cover: Aurora borealis paintings by William Crowder, National Geographic (1947). The International Geophysical Year (1957–8) transformed research on the aurora, one of nature’s most elusive and intensely beautiful phenomena. Aurorae became the center of interest for the big science of powerful rockets, complex satellites and large group efforts to understand the magnetic and charged particle environment of the earth. The auroral visoplot displayed here provided guidance for recording observations in a standardized form, translating the sublime aesthetics of pictorial depictions of aurorae into the mechanical aesthetics of numbers and symbols. Most of the portait photographs were taken by Skúli Sigurdsson RESEARCH REPORT 2010—2012 MAX-PLANCK-INSTITUT FÜR WISSENSCHAFTSGESCHICHTE Max Planck Institute for the History of Science Introduction The Max Planck Institute for the History of Science (MPIWG) is made up of three Departments, each administered by a Director, and several Independent Research Groups, each led for five years by an outstanding junior scholar. Since its foundation in 1994 the MPIWG has investigated fundamental questions of the history of knowl- edge from the Neolithic to the present. The focus has been on the history of the natu- ral sciences, but recent projects have also integrated the history of technology and the history of the human sciences into a more panoramic view of the history of knowl- edge. Of central interest is the emergence of basic categories of scientific thinking and practice as well as their transformation over time: examples include experiment, ob- servation, normalcy, space, evidence, biodiversity or force. -

George Porter

G EORGE P O R T E R Flash photolysis and some of its applications Nobel Lecture, December 11, 1967 One of the principal activities of man as scientist and technologist has been the extension of the very limited senses with which he is endowed so as to enable him to observe phenomena with dimensions very different from those he can normally experience. In the realm of the very small, microscopes and micro- balances have permitted him to observe things which have smaller extension or mass than he can see or feel. In the dimension of time, without the aid of special techniques, he is limited in his perception to times between about one twentieth of a second ( the response time of the eye) and about 2·10 9 seconds (his lifetime). Y et most of the fundamental processes and events, particularly those in the molecular world which we call chemistry, occur in milliseconds or less and it is therefore natural that the chemist should seek methods for the study of events in microtime. My own work on "the study of extremely fast chemical reactions effected by disturbing the equilibrium by means of very short pulses of energy" was begun in Cambridge twenty years ago. In 1947 I attended a discussion of the Faraday Society on "The Labile Molecule". Although this meeting was en- tirely concerned with studies of short lived chemical substances, the four hundred pages of printed discussion contain little or no indication of the im- pending change in experimental approach which was to result from the intro- . -

C.P. Snow the REDE LECTURE, 1959

C.P. Snow THE REDE LECTURE, 1959 © Cambridge University Press 1 THE TWO CULTURES It is about three years since I made a sketch in print of a problem which had been on my mind for some time. 1 It was a problem I could not avoid just because of the circumstances of my life. The only credentials I had to ruminate on the subject at all came through those circumstances, through nothing more than a set of chances. Anyone with similar experience would have seen much the same things and I think made very much the same comments about them. It just happened to be an unusual experience. By training I was a scientist: by vocation I was a writer. That was all. It was a piece of luck, if you like, that arose through coming from a poor home. But my personal history isn't the point now. All that I need say is that I came to Cambridge and did a bit of research here at a time of major scientific activity. I was privileged to have a ringside view of one of the most wonderful creative periods in all physics. And it happened through the flukes of war— including meeting W. L. Bragg in the buffet on Kettering station on a very cold morning in 1939, which had a determining influence on my practical life—that I was able, and indeed morally forced, to keep that ringside view ever since. So for thirty years I have had to be in touch with scientists not only out of curiosity, but as part of a working existence. -

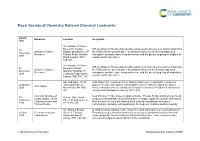

RSC Branding

Royal Society of Chemistry National Chemical Landmarks Award Honouree Location Inscription Date The Institute of Cancer Research, Chester ICR scientists on this site and elsewhere pioneered numerous new cancer drugs from 10 Institute of Cancer Beatty Laboratories, 237 the 1950s until the present day – including the discovery of chemotherapy drug December Research Fulham Road, Chelsea carboplatin, prostate cancer drug abiraterone and the genetic targeting of olaparib for 2018 Road, London, SW3 ovarian and breast cancer. 6JB, UK The Institute of Cancer ICR scientists on this site and elsewhere pioneered numerous new cancer drugs from 10 Research, Royal Institute of Cancer the 1950s until the present day – including the discovery of chemotherapy drug December Marsden Hospital, 15 Research carboplatin, prostate cancer drug abiraterone and the genetic targeting of olaparib for 2018 Cotswold Road, Sutton, ovarian and breast cancer. London, SM2 5NG, UK Ape and Apple, 28-30 John Dalton Street was opened in 1846 by Manchester Corporation in honour of 26 October John Dalton Street, famous chemist, John Dalton, who in Manchester in 1803 developed the Atomic John Dalton 2016 Manchester, M2 6HQ, Theory which became the foundation of modern chemistry. President of Manchester UK Literary and Philosophical Society 1816-1844. Chemical structure of Near this site in 1903, James Colquhoun Irvine, Thomas Purdie and their team found 30 College Gate, North simple sugars, James a way to understand the chemical structure of simple sugars like glucose and lactose. September Street, St Andrews, Fife, Colquhoun Irvine and Over the next 18 years this allowed them to lay the foundations of modern 2016 KY16 9AJ, UK Thomas Purdie carbohydrate chemistry, with implications for medicine, nutrition and biochemistry. -

Nobel Lectures™ 2001-2005

World Scientific Connecting Great Minds 逾10 0 种 诺贝尔奖得主著作 及 诺贝尔奖相关图书 我们非常荣幸得以出版超过100种诺贝尔奖得主著作 以及诺贝尔奖相关图书。 我们自1980年代开始与诺贝尔奖得主合作出版高品质 畅销书。一些得主担任我们的编辑顾问、丛书编辑, 并于我们期刊发表综述文章与学术论文。 世界科技与帝国理工学院出版社还邀得其中多位作了公 开演讲。 Philip W Anderson Sir Derek H R Barton Aage Niels Bohr Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar Murray Gell-Mann Georges Charpak Nicolaas Bloembergen Baruch S Blumberg Hans A Bethe Aaron J Ciechanover Claude Steven Chu Cohen-Tannoudji Leon N Cooper Pierre-Gilles de Gennes Niels K Jerne Richard Feynman Kenichi Fukui Lawrence R Klein Herbert Kroemer Vitaly L Ginzburg David Gross H Gobind Khorana Rita Levi-Montalcini Harry M Markowitz Karl Alex Müller Sir Nevill F Mott Ben Roy Mottelson 诺贝尔奖相关图书 THE PERIODIC TABLE AND A MISSED NOBEL PRIZES THAT CHANGED MEDICINE NOBEL PRIZE edited by Gilbert Thompson (Imperial College London) by Ulf Lagerkvist & edited by Erling Norrby (The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences) This book brings together in one volume fifteen Nobel Prize- winning discoveries that have had the greatest impact upon medical science and the practice of medicine during the 20th “This is a fascinating account of how century and up to the present time. Its overall aim is to groundbreaking scientists think and enlighten, entertain and stimulate. work. This is the insider’s view of the process and demands made on the Contents: The Discovery of Insulin (Robert Tattersall) • The experts of the Nobel Foundation who Discovery of the Cure for Pernicious Anaemia, Vitamin B12 assess the originality and significance (A Victor Hoffbrand) • The Discovery of -

Guides to the Royal Institution of Great Britain: 1 HISTORY

Guides to the Royal Institution of Great Britain: 1 HISTORY Theo James presenting a bouquet to HM The Queen on the occasion of her bicentenary visit, 7 December 1999. by Frank A.J.L. James The Director, Susan Greenfield, looks on Front page: Façade of the Royal Institution added in 1837. Watercolour by T.H. Shepherd or more than two hundred years the Royal Institution of Great The Royal Institution was founded at a meeting on 7 March 1799 at FBritain has been at the centre of scientific research and the the Soho Square house of the President of the Royal Society, Joseph popularisation of science in this country. Within its walls some of the Banks (1743-1820). A list of fifty-eight names was read of gentlemen major scientific discoveries of the last two centuries have been made. who had agreed to contribute fifty guineas each to be a Proprietor of Chemists and physicists - such as Humphry Davy, Michael Faraday, a new John Tyndall, James Dewar, Lord Rayleigh, William Henry Bragg, INSTITUTION FOR DIFFUSING THE KNOWLEDGE, AND FACILITATING Henry Dale, Eric Rideal, William Lawrence Bragg and George Porter THE GENERAL INTRODUCTION, OF USEFUL MECHANICAL - carried out much of their major research here. The technological INVENTIONS AND IMPROVEMENTS; AND FOR TEACHING, BY COURSES applications of some of this research has transformed the way we OF PHILOSOPHICAL LECTURES AND EXPERIMENTS, THE APPLICATION live. Furthermore, most of these scientists were first rate OF SCIENCE TO THE COMMON PURPOSES OF LIFE. communicators who were able to inspire their audiences with an appreciation of science.