IALL2017): Law, Language and Justice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teaching Pronunciation Communicatively to Cape Verdean English Language Learners: Sao Vicente Variety Jacira Monteiro

Bridgewater State University Virtual Commons - Bridgewater State University Master’s Theses and Projects College of Graduate Studies 5-13-2015 Teaching Pronunciation Communicatively to Cape Verdean English Language Learners: Sao Vicente Variety Jacira Monteiro Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/theses Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Monteiro, Jacira. (2015). Teaching Pronunciation Communicatively to Cape Verdean English Language Learners: Sao Vicente Variety. In BSU Master’s Theses and Projects. Item 19. Available at http://vc.bridgew.edu/theses/19 Copyright © 2015 Jacira Monteiro This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Teaching pronunciation communicatively to Cape Verdean English language learners / Sao Vicente variety by Jacira Monteiro MA, Bridgewater State University, 2015 Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Teaching [TESOL] Bridgewater State University May 13, 2015 Teaching pronunciation communicatively to Cape Verdean ELLs/Sao Vicente variety Thesis Presented by: Jacira Monteiro Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Teaching English for Students of Other Languages Spring 2015 Content and Style Approved By: ___________________________________________ _______________ Dr. Anne Doyle, Chair of Thesis Committee Date ___________________________________________ _______________ Dr. Julia Stakhnevich, Committee Member Date __________________________________________ _______________ Dr. Joyce Rain Anderson, Committee Member Date Acknowledgement I would like to express a special thanks to my mother and father. To Mr. Rendall for sharing his experience on this matter. To my advisor professor Doyle for her guidance, months of generously sharing her time and support. -

The Experience of Emergent Bilingual Cape Verdean Middle School Students

University of Rhode Island DigitalCommons@URI Open Access Dissertations 2019 Navigating Internal and External Borderlands: The Experience of Emergent Bilingual Cape Verdean Middle School Students Abigale E. Jansen University of Rhode Island, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss Recommended Citation Jansen, Abigale E., "Navigating Internal and External Borderlands: The Experience of Emergent Bilingual Cape Verdean Middle School Students" (2019). Open Access Dissertations. Paper 852. https://digitalcommons.uri.edu/oa_diss/852 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@URI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@URI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NAVIGATING INTERNAL AND EXTERNAL BORDERLANDS: THE EXPERIENCE OF EMERGENT BILINGUAL CAPE VERDEAN MIDDLE SCHOOL STUDENTS BY ABIGALE E. JANSEN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN EDUCATION UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND AND RHODE ISLAND COLLEGE 2019 DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DISSERTATION OF ABIGALE E. JANSEN APPROVED: Dissertation Committee Major Professor: Gerri August Sarah Hesson Minsuk Shim Kathy Pino RIC: Julie Horwitz, Interim Co-Dean, Feinstein School of Education – RIC Gerri August, Interim Co-Dean, Feinstein School of Education – RIC URI: Nasser H. Zawia, Dean, The Graduate School - URI UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND AND RHODE ISLAND COLLEGE 2019 ABSTRACT The purpose of this grounded theory research study was to better understand the experiences of emergent bilingual Cape Verdean Middle School students as they navigate internal and external borderlands. This study was conducted in an urban middle school in New England. -

ASR-X Pro 3.00

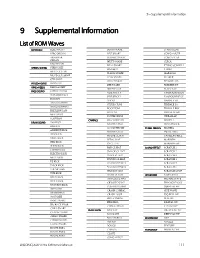

9ÑSupplemental Information 9 Suppll ementttall II nffformatttii on Lii sttt offf ROM Waves KEYBOARD ELEC PIANO JAMM SNARE CONGA LOW PERC ORGAN LIVE SNARE CONGA MUTE DRAWBAR LUDWIG SNARE CONGA SLAP ORGAN MUTT SNARE CUICA PAD SYNTH REAL SNARE ETHNO COWBELL STRII NG-SOUND STRING HIT RIMSHOT GUIRO MUTE GUITAR SLANG SNARE MARACAS MUTE GUITARWF SPAK SNARE SHAKER GTR-SLIDE WOLF SNARE SHEKERE DN BRASS+HORNS HORN HIT ZEE SNARE SHEKERE UP WII ND+REEDS BARI SAX HIT BRUSH SLAP SLAP CLAP BASS-SOUND UPRIGHT BASS SIDE STICK 1 TAMBOURINE DN BS HARMONICS SIDE STICK 2 TAMBOURINE UP FM BASS STICKS TIMBALE HI ANALOG BASS 1 STUDIO TOM TIMBALE LO ANALOG BASS 2 ROCK TOM TIMBALE RIM FRETLESS BASS 909 TOM TRIANGLE HIT MUTE BASS SYNTH DRUM VIBRASLAP SLAP BASS CYMBALS 808 CLOSED HT WHISTLE DRUM-SOUND 2001 KICK 808 OPEN HAT WOODBLOCK 808 KICK 909 CLOSED HT TUNED-PERCUS BIG BELL AMBIENT KICK 909 OPEN HAT SMALL BELL BAM KICK HOUSE CL HAT GAMELAN BELL BANG KICK PEDAL HAT MARIMBA BBM KICK PZ CL HAT MARIMBA WF BOOM KICK R&B CL HAT SOUND-EFFECT SCRATCH 1 COSMO KICK SMACK CL HAT SCRATCH 2 ELECTRO KICK SNICK CL HAT SCRATCH 3 MUFF KICK STUDIO CL HAT SCRATCH 4 PZ KICK STUDIO OPHAT1 SCRATCH 5 SNICK KICK STUDIO OPHAT2 SCRATCH 6 THUMP KICK TECHNO HAT SCRATCH LOOP TITE KICK TIGHT CL HAT WAVEFORM SAWTOOTH WILD KICK TRANCE CL HAT SQUARE WAVE WOLF KICK CR78 OPENHAT TRIANGLE WAV WOO BOX KICK COMPRESS OPHT SQR+SAW WF 808 SNARE CRASH CYMBAL SINE WAVE 808 RIMSHOT CRASH LOOP ESQ BELL WF 909 SNARE RIDE CYMBAL BELL WF BANG SNARE RIDE BELL DIGITAL WF BIG ROCK SNAR CHINA CRASH E PIANO WF -

Different Ecological Processes Determined the Alpha and Beta Components of Taxonomic, Functional, and Phylogenetic Diversity

Different ecological processes determined the alpha and beta components of taxonomic, functional, and phylogenetic diversity for plant communities in dryland regions of Northwest China Jianming Wang1, Chen Chen1, Jingwen Li1, Yiming Feng2 and Qi Lu2 1 College of Forestry, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China 2 Institute of Desertification Studies, Chinese Academy of Forestry, Beijing, China ABSTRACT Drylands account for more than 30% of China’s terrestrial area, while the ecological drivers of taxonomic (TD), functional (FD) and phylogenetic (PD) diversity in dryland regions have not been explored simultaneously. Therefore, we selected 36 plots of desert and 32 plots of grassland (10 Â 10 m) from a typical dryland region of northwest China. We calculated the alpha and beta components of TD, FD and PD for 68 dryland plant communities using Rao quadratic entropy index, which included 233 plant species. Redundancy analyses and variation partitioning analyses were used to explore the relative influence of environmental and spatial factors on the above three facets of diversity, at the alpha and beta scales. We found that soil, climate, topography and spatial structures (principal coordinates of neighbor matrices) were significantly correlated with TD, FD and PD at both alpha and beta scales, implying that these diversity patterns are shaped by contemporary environment and spatial processes together. However, we also found that alpha diversity was predominantly regulated by spatial structure, whereas beta diversity was largely determined by environmental variables. Among environmental factors, TD was Submitted 10 June 2018 most strongly correlated with climatic factors at the alpha scale, while 5 December 2018 Accepted with soil factors at the beta scale. -

2018 DG Report on the Safety of Journalists and the Danger of Impunity

CI-18/COUNCIL-31/6/REV 2 2018 DG Report on the Safety of Journalists and the Danger of Impunity INTRODUCTION This report is submitted to the Intergovernmental Council of the International Programme for the Development of Communication (IPDC) in line with the Decision on the Safety of Journalists and the issue of Impunity adopted by the Council at its 26th session on 27 March 2008, and renewed at subsequent sessions in 2010, 2012, 2014 and 2016. In its latest Decision, adopted in November 2016, the IPDC Council urged Member States to “continue to inform the Director-General of UNESCO, on a voluntary basis, on the status of the judicial inquiries conducted on each of the killings condemned by the Director-General”. The present report provides an analysis of the cases of killings of journalists and associated media personnel that were condemned by the Director-General in 2016 and 2017. It also takes stock of the status of judicial enquiries conducted on each of the killings recorded by UNESCO between 2006 and 2017, based on information provided by Member States. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary 2 2. Background and Context 2 3. Journalists’ killings in 2016 and 2017: key findings 7 3.1 Most dangerous regions 8 3.2 Rise in number of women journalists among fatalities 9 3.3 Highest number of killings among TV journalists 11 3.4 Majority of victims are local journalists 11 3.5 Freelance and staff journalists 12 3.6 More killings occurring in countries with no armed conflict 12 4. Member States’ responses: status of the judicial enquiries on cases of journalists killed from 2006 to end 2017 13 4.1 Decrease in Member State response rate to Director-General’s request 18 4.2 Slight reduction in impunity rate, but 89% of cases remain unresolved 19 4.3 Member States reporting on measures to promote safety of journalists and to combat impunity 22 5. -

Does Successful Small-Scale Coordination Help Or Hinder

The Iberian Challenge: Creole languages beyond the plantation setting. Edited by Armin Schwegler, John McWhorter & Liane Ströbel. Madrid/Frankfurt am Main: Iberoamericana-Vervuert, 2016. Pp. viii, 273 Paperback $39.60 To order, visit https://www.iberoamericana- vervuert.es/. Reviewed by J. Clancy Clements (Indiana University-Bloomington) As the title suggests, this collection of scholarly articles deals with non-plantation creoles, covers individual creoles, creoles in a region, creoles lexified by Spanish, palenques as the locus for creole formation/development, and archival documents as a source for better understanding the formation and development of Por- tuguese-lexified creoles in West Africa. In ‘The missing Spanish creole are still missing: Revisiting Afrogenesis and its implications for a coherent theory of creole genesis’ (pp.39–66), John McWhorter again weighs in on the complex question of the origins of these contact languages, with a focus on the Spanish-based creoles. Using socio-historical data and com- paring the evolution of various English-, French-, Portuguese-, and Spanish-lex- ified contact vernaculars, McWhorter lays out the hypothesis that these did not begin on plantations but rather in slave castles in West Africa, and were then transported to places where plantations already existed. For the Spanish creoles, this thesis is of particular relevance because in the last decade sociohistorical research has shown that there are increasingly fewer former Spanish colonies where one might expect a plantation creole to have emerged. One additional point seems relevant: the reason that there are no Portuguese-based creoles in Brazil (a question McWhorter raises at the end) may be due to what Schwartz (1985) doc- uments earlier in colonial Brazil: many African slaves worked in smaller commu- nities and had greater access to Portuguese. -

Cape Verdean Kriolu As an Epistemology of Contact O Crioulo Cabo-Verdiano Como Epistemologia De Contato

Cadernos de Estudos Africanos 24 | 2012 Africanos e Afrodescendentes em Portugal: Redefinindo Práticas, Projetos e Identidades Cape Verdean Kriolu as an Epistemology of Contact O crioulo cabo-verdiano como epistemologia de contato Derek Pardue Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/cea/696 DOI: 10.4000/cea.696 ISSN: 2182-7400 Publisher Centro de Estudos Internacionais Printed version Number of pages: 73-94 ISSN: 1645-3794 Electronic reference Derek Pardue, « Cape Verdean Kriolu as an Epistemology of Contact », Cadernos de Estudos Africanos [Online], 24 | 2012, Online since 13 December 2012, connection on 01 May 2019. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/cea/696 ; DOI : 10.4000/cea.696 O trabalho Cadernos de Estudos Africanos está licenciado com uma Licença Creative Commons - Atribuição-NãoComercial-CompartilhaIgual 4.0 Internacional. Cadernos de Estudos Africanos (2012) 24, 73-94 © 2012 Centro de Estudos Africanos do ISCTE - Instituto Universitário de Lisboa Ca Va Ki a a Eiy Ca Derek Pardue Universidade de Washington St. Louis, E.U.A. [email protected] 74 CAPE VERDEAN KRIOLU AS AN EPISTEMOLOGY OF CONTACT Cape Verdean Kriolu as an epistemology of contact Kriolu as language and sentiment represents a “contact perspective”, an outlook on life and medium of identiication historically structured by the encounter. Cape Verde was born out of an early creole formation and movement is an essential part of Cape Verdean practices of language and identity. Most recently, the Portuguese state and third-party real estate developers have provided another scenario in the long series of (dis) emplacement dramas for Cape Verdeans as Lisbon administrations have pushed to demol- ish “improvised” housing and regroup people into “social” neighborhoods. -

General Conclusions and Basic Tendencies 1. System of Human Rights Violations

REVIEW-CHRONICLE OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN BELARUS IN 2003 2 REVIEW-CHRONICLE OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS IN BELARUS IN 2003 INTRODUCTION: GENERAL CONCLUSIONS AND BASIC TENDENCIES 1. SYSTEM OF HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS The year 2003 was marked by deterioration of the human rights situation in Belarus. While the general human rights situation in the country did not improve, in its certain spheres it significantly changed for the worse. Disrespect for and regular violations of the basic constitutional civic rights became an unavoidable and permanent factor of the Belarusian reality. In 2003 the Belarusian authorities did not even hide their intention to maximally limit the freedom of speech, freedom of association, religious freedom, and human rights in general. These intentions of the ruling regime were declared publicly. It was a conscious and open choice of the state bodies constituting one of the strategic elements of their policy. This political process became most visible in formation and forced intrusion of state ideology upon the citizens. Even leaving aside the question of the ideology contents, the very existence of an ideology, compulsory for all citizens of the country, imposed through propaganda media and educational establishments, and fraught with punitive sanctions for any deviation from it, is a phenomenon, incompatible with the fundamental human right to have a personal opinion. Thus, the state policy of the ruling government aims to create ideological grounds for consistent undermining of civic freedoms in Belarus. The new ideology is introduced despite the Constitution of the Republic of Belarus which puts a direct ban on that. -

Seeking Justice for Pavel Sheremet

July 20, 2017 IN BRIEF One Year Later: Seeking Justice for Pavel Sheremet Concerning Trends for Press Freedom in Ukraine When investigative journalist Pavel Sheremet died in a car explosion in central Kyiv on July 20, 2016, his assassination garnered global media attention. Upon learning the tragic news, then- OSCE Representative on Freedom of the Media Dunja Mijatović condemned the murder, saying, “This killing and its circumstances must be swiftly and thoroughly investigated, and the 1 perpetrators brought to justice.” However, one year later, virtually no progress has been made on his case. Furthermore, the An internationally acclaimed journalist, Pavel Sheremet received the International escalating harassment and attacks against jour- Press Freedom Award from the Committee nalists in Ukraine, coupled with a culture of im- to Protect Journalists in 1998, and the punity for perpetrators, is worrisome for OSCE’s Prize for Journalism and Democracy Ukraine’s democratic future. To ensure they in recognition of his human rights reporting meet the aspirations of the Ukrainian people, in the Balkans and Afghanistan in 2002. (Photo credit: Okras) authorities in Kiev must reaffirm their com- mitment to freedom of the press by ensuring the perpetrators of Sheremet’s murder—and left Russia—again as a result of mounting hos- similar cases of killing, assault, and harass- tility from the host regime he criticized—and ment—are brought to justice. moved to Kyiv. At the time of his death, Shemeret had lived in Kyiv for five years with Investigative Journalist and Outspoken Critic Ukrainska Pravda editor-in-chief Olena Prytula. A regular contributor to popular news site Ukrainska Pravda, Sheremet was known for In 2000, Sheremet’s cameraman, Dmitry Zavad- challenging the authorities in his home country sky, disappeared in Minsk after shooting a doc- of Belarus as well as in his adopted homes of umentary about the war in Chechnya. -

Papia 21.2.Pmd

A LÍNGUA PBANTUAPIA 21(2), ANGOLANA p. 315-334, MBWELA (K17) 2011. EISSN A BUSCA 0103-9415 ETIMOLÓGICA... 315 CAPE VERDEAN TA IN ITS ROLE AS A PROGRESSIVE ASPECT MARKER Bart Jacobs Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München [email protected] Abstract: This paper deals with the aspectual properties of the preverbal marker ta as used in Cape Verdean Creole (CV). It will be argued that, counter to what is generally held in the literature, CV ta marks not only habitual but also progressive aspect, most notably in gerundive complement clauses, but also in periphrastic progressive markers found throughout the CV dialect cluster. An added aim is to show that, as a progressive marker, CV ta behaves remarkably similar to its Papiamentu (PA) cognate ta, whose status as a general imperfective marker ([+ha- bitual, +progressive]) is widely recognized. This way, Maurer’s (2009) claim that the aspect markers CV ta and PA ta are qualitatively different is proven to be invalid. Keywords: Cape Verdean Creole, Papiamentu, progressive aspect. 1. Introduction1 This paper reassesses the aspectual properties of the preverbal marker ta as used in Cape Verdean Creole (CV)2. It will be argued that, counter to 1 I am grateful to Dominika Swolkien, Incanha Intumbo, Octavio Fontes, Bernardino Tavares, Gabriel Antunes de Araujo, Noël Bernard Biagui, and Nicolas Quint for valuable comments, suggestions and personal communications. Any shortcomings are solely my responsibility. 2 CV is spoken on the Cape Verde Islands, situated off the coast of Senegal. Within the CV dialect cluster, a rough distinction must be made between the varieties of Barlavento and Sotavento. -

Tuning, Timbre, Spectrum, Scale William A

Tuning, Timbre, Spectrum, Scale William A. Sethares Tuning, Timbre, Spectrum, Scale Second Edition With 149 Figures William A. Sethares, Ph.D. Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering University of Wisconsin–Madison 1415 Johnson Drive Madison, WI 53706-1691 USA British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Sethares, William A., 1955– Tuning, timbre, spectrum, scale.—2nd ed. 1. Sound 2. Tuning 3. Tone color (Music) 4. Musical intervals and scales 5. Psychoacoustics 6. Music—Acoustics and physics I. Title 781.2′3 ISBN 1852337974 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sethares, William A., 1955– Tuning, timbre, spectrum, scale / William A. Sethares. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-85233-797-4 (alk. paper) 1. Sound. 2. Tuning. 3. Tone color (Music) 4. Musical intervals and scales. 5. Psychoacoustics. 6. Music—Acoustics and physics. I. Title. QC225.7.S48 2004 534—dc22 2004049190 Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries con- cerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers. ISBN 1-85233-797-4 2nd edition Springer-Verlag London Berlin Heidelberg ISBN 3-540-76173-X 1st edition Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg New York Springer Science+Business Media springeronline.com © Springer-Verlag London Limited 2005 Printed in the United States of America First published 1999 Second edition 2005 The software disk accompanying this book and all material contained on it is supplied without any warranty of any kind. -

L:\Hearings 2018\09-06 Zzdistill\32635.Txt

S. HRG. 115–376 OUTSIDE PERSPECTIVES ON RUSSIA SANCTIONS: CURRENT EFFECTIVENESS AND POTENTIAL FOR NEXT STEPS HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON BANKING, HOUSING, AND URBAN AFFAIRS UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FIFTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION ON EXAMINING THE IMPLEMENTATION AND EFFECTIVENESS OF THE SANCTIONS PROGRAM CURRENTLY IN PLACE AGAINST RUSSIA AND THE EFFECTS OF THOSE SANCTIONS SEPTEMBER 6, 2018 Printed for the use of the Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs ( Available at: https://www.govinfo.gov/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 32–635 PDF WASHINGTON : 2019 COMMITTEE ON BANKING, HOUSING, AND URBAN AFFAIRS MIKE CRAPO, Idaho, Chairman RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama SHERROD BROWN, Ohio BOB CORKER, Tennessee JACK REED, Rhode Island PATRICK J. TOOMEY, Pennsylvania ROBERT MENENDEZ, New Jersey DEAN HELLER, Nevada JON TESTER, Montana TIM SCOTT, South Carolina MARK R. WARNER, Virginia BEN SASSE, Nebraska ELIZABETH WARREN, Massachusetts TOM COTTON, Arkansas HEIDI HEITKAMP, North Dakota MIKE ROUNDS, South Dakota JOE DONNELLY, Indiana DAVID PERDUE, Georgia BRIAN SCHATZ, Hawaii THOM TILLIS, North Carolina CHRIS VAN HOLLEN, Maryland JOHN KENNEDY, Louisiana CATHERINE CORTEZ MASTO, Nevada JERRY MORAN, Kansas DOUG JONES, Alabama GREGG RICHARD, Staff Director MARK POWDEN, Democratic Staff Director JOHN O’HARA, Chief Counsel for National Security Policy KRISTINE JOHNSON, Economist ELISHA TUKU, Democratic Chief Counsel LAURA SWANSON, Democratic Deputy Staff Director COLIN MCGINNIS, Democratic Policy Director DAWN RATLIFF, Chief Clerk CAMERON