Tuning, Timbre, Spectrum, Scale William A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

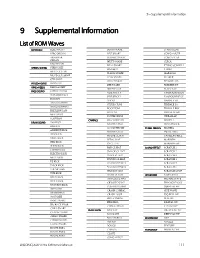

ASR-X Pro 3.00

9ÑSupplemental Information 9 Suppll ementttall II nffformatttii on Lii sttt offf ROM Waves KEYBOARD ELEC PIANO JAMM SNARE CONGA LOW PERC ORGAN LIVE SNARE CONGA MUTE DRAWBAR LUDWIG SNARE CONGA SLAP ORGAN MUTT SNARE CUICA PAD SYNTH REAL SNARE ETHNO COWBELL STRII NG-SOUND STRING HIT RIMSHOT GUIRO MUTE GUITAR SLANG SNARE MARACAS MUTE GUITARWF SPAK SNARE SHAKER GTR-SLIDE WOLF SNARE SHEKERE DN BRASS+HORNS HORN HIT ZEE SNARE SHEKERE UP WII ND+REEDS BARI SAX HIT BRUSH SLAP SLAP CLAP BASS-SOUND UPRIGHT BASS SIDE STICK 1 TAMBOURINE DN BS HARMONICS SIDE STICK 2 TAMBOURINE UP FM BASS STICKS TIMBALE HI ANALOG BASS 1 STUDIO TOM TIMBALE LO ANALOG BASS 2 ROCK TOM TIMBALE RIM FRETLESS BASS 909 TOM TRIANGLE HIT MUTE BASS SYNTH DRUM VIBRASLAP SLAP BASS CYMBALS 808 CLOSED HT WHISTLE DRUM-SOUND 2001 KICK 808 OPEN HAT WOODBLOCK 808 KICK 909 CLOSED HT TUNED-PERCUS BIG BELL AMBIENT KICK 909 OPEN HAT SMALL BELL BAM KICK HOUSE CL HAT GAMELAN BELL BANG KICK PEDAL HAT MARIMBA BBM KICK PZ CL HAT MARIMBA WF BOOM KICK R&B CL HAT SOUND-EFFECT SCRATCH 1 COSMO KICK SMACK CL HAT SCRATCH 2 ELECTRO KICK SNICK CL HAT SCRATCH 3 MUFF KICK STUDIO CL HAT SCRATCH 4 PZ KICK STUDIO OPHAT1 SCRATCH 5 SNICK KICK STUDIO OPHAT2 SCRATCH 6 THUMP KICK TECHNO HAT SCRATCH LOOP TITE KICK TIGHT CL HAT WAVEFORM SAWTOOTH WILD KICK TRANCE CL HAT SQUARE WAVE WOLF KICK CR78 OPENHAT TRIANGLE WAV WOO BOX KICK COMPRESS OPHT SQR+SAW WF 808 SNARE CRASH CYMBAL SINE WAVE 808 RIMSHOT CRASH LOOP ESQ BELL WF 909 SNARE RIDE CYMBAL BELL WF BANG SNARE RIDE BELL DIGITAL WF BIG ROCK SNAR CHINA CRASH E PIANO WF -

Different Ecological Processes Determined the Alpha and Beta Components of Taxonomic, Functional, and Phylogenetic Diversity

Different ecological processes determined the alpha and beta components of taxonomic, functional, and phylogenetic diversity for plant communities in dryland regions of Northwest China Jianming Wang1, Chen Chen1, Jingwen Li1, Yiming Feng2 and Qi Lu2 1 College of Forestry, Beijing Forestry University, Beijing, China 2 Institute of Desertification Studies, Chinese Academy of Forestry, Beijing, China ABSTRACT Drylands account for more than 30% of China’s terrestrial area, while the ecological drivers of taxonomic (TD), functional (FD) and phylogenetic (PD) diversity in dryland regions have not been explored simultaneously. Therefore, we selected 36 plots of desert and 32 plots of grassland (10 Â 10 m) from a typical dryland region of northwest China. We calculated the alpha and beta components of TD, FD and PD for 68 dryland plant communities using Rao quadratic entropy index, which included 233 plant species. Redundancy analyses and variation partitioning analyses were used to explore the relative influence of environmental and spatial factors on the above three facets of diversity, at the alpha and beta scales. We found that soil, climate, topography and spatial structures (principal coordinates of neighbor matrices) were significantly correlated with TD, FD and PD at both alpha and beta scales, implying that these diversity patterns are shaped by contemporary environment and spatial processes together. However, we also found that alpha diversity was predominantly regulated by spatial structure, whereas beta diversity was largely determined by environmental variables. Among environmental factors, TD was Submitted 10 June 2018 most strongly correlated with climatic factors at the alpha scale, while 5 December 2018 Accepted with soil factors at the beta scale. -

IALL2017): Law, Language and Justice

Proceedings of The Fifteenth International Conference on Law and Language of the International Academy of Linguistic Law (IALL2017): Law, Language and Justice May, 16-18, 2017 Hangzhou, China and Montréal, Québec, Canada Chief Editors: Ye Ning, Joseph-G. Turi, and Cheng Le Editors: Lisa Hale, and Jin Zhang Cover Designer: Lu Xi Published by The American Scholars Press, Inc. The Proceedings of The Fifteenth International Conference on Law, Language of the International Academy of Linguistic Law (IALL2017): Law, Language, and Justice is published by the American Scholars Press, Inc., Marietta, Georgia, USA. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. Copyright © 2017 by the American Scholars Press All rights reserved. ISBN: 978-0-9721479-7-2 Printed in the United States of America 2 Foreword In this sunny and green early summer, you, experts and delegates from different parts of the world, come together beside the Qiantang River in Hangzhou, to participate in The Fifteenth International Conference on Law and Language of the International Academy of Linguistic Law. On the occasion of the opening ceremony, it gives me such great pleasure on behalf of Zhejiang Police College, and also on my own part, to extend a warm welcome to all the distinguished experts and delegates. At the same time, thanks for giving so much trust and support to Zhejiang Police College. Currently, the law-based governance of the country is comprehensively promoted in China. As Xi Jinping, Chinese president, said, “during the entire reform process, we should attach great importance to applying the idea of rule of law and the way of rule of law to play the leading and driving role of rule of law”. -

On the Bimodular Approximation and Equal Temperaments

On the Bimodular Approximation and Equal Temperaments Martin Gough DRAFT June 8 2014 Abstract The bimodular approximation, which has been known for over 300 years as an accurate means of computing the relative sizes of small (sub-semitone) musical intervals, is shown to provide a remarkably good approximation to the sizes of larger intervals, up to and beyond the size of the octave. If just intervals are approximated by their bimodular approximants (rational numbers defined as frequency difference divided by frequency sum) the ratios between those intervals are also rational, and under certain simply stated conditions can be shown to coincide with the integer ratios which equal temperament imposes on the same intervals. This observation provides a simple explanation for the observed accuracy of certain equal divisions of the octave including 12edo, as well as non-octave equal temperaments such as the fifth-based temperaments of Wendy Carlos. Graphical presentations of the theory provide further insights. The errors in the bimodular approximation can be expressed as bimodular commas, among which are many commas featuring in established temperament theory. Introduction Just musical intervals are characterised by small-integer ratios between frequencies. Equal temperaments, by contrast, are characterised by small-integer ratios between intervals. Since interval is the logarithm of frequency ratio, it follows that an equal temperament which accurately represents just intervals embodies a set of rational approximations to the logarithms (to some suitable base) of simple rational numbers. This paper explores the connection between these rational logarithmic approximations and those obtained from a long-established rational approximation to the logarithm function – the bimodular approximation. -

The Diachronic Development and Synchronic Distribution of Minimizers in Mandarin Chinese

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics Title The Diachronic Development and Synchronic Distribution of Minimizers in Mandarin Chinese Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0g29672q Author Chen, I-Hsuan Publication Date 2015-07-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Diachronic Development and Synchronic Distribution of Minimizers in Mandarin Chinese By I-Hsuan Chen A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Eve E. Sweetser, Chair Professor Gary B. Holland Professor Peter S. Jenks Professor Darya A. Kavitskaya Summer 2015 The Diachronic Development and Synchronic Distribution of Minimizers in Mandarin Chinese Copyright © 2015 By I-Hsuan Chen Abstract The Diachronic Development and Synchronic Distribution of Minimizers in Mandarin Chinese By I-Hsuan Chen Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Professor Eve E. Sweetser, Chair This study deals with the historical development of Mandarin minimizers through examining their synchronic distribution. The main source of Mandarin minimizers, a distinct class of negative polarity items (NPIs), is ‘one’-phrases which are composed of the numeral ‘one’, a unit word, and a noun. The development of ‘one’-phrases as minimizers from Old Chinese, Middle Chinese, Early Mandarin, to Modern Mandarin makes strong links among important linguistic issues such as NPI licensing, word order, numeral-classifier phrases, and focus constructions. The diachronic development of the ‘one’-phrases as minimizers is analyzed from a constructional approach. The present study shows that the unit of these diachronic changes is the whole ‘one’-phrase construction instead of merely the lexical items. -

A Reconstruction of Proto-Jê Phonology and Lexicon1

Российский государственный гуманитарный университет Russian State University for the Humanities Russian State University for the Humanities Institute of Linguistics of the Russian Academy of Sciences Journal of Language Relationship International Scientific Periodical Nº 17/2 Moscow 2019 Российский государственный гуманитарный университет Институт языкознания Российской Академии наук Вопросы языкового родства Международный научный журнал № 17/2 Москва 2019 Advisory Board: H.EICHNER (Vienna) / Chairman W.BAXTER (Ann Arbor, Michigan) V.BLAŽEK (Brno) M.GELL-MANN (Santa Fe, New Mexico) L.HYMAN (Berkeley) F.KORTLANDT (Leiden) A.LUBOTSKY (Leiden) J. P. MALLORY (Belfast) A.YU. MILITAREV (Moscow) V. F. VYDRIN (Paris) Editorial Staff: V. A. DYBO (Editor-in-Chief) G. S. STAROSTIN (Managing Editor) T. A. MIKHAILOVA (Editorial Secretary) A. V. DYBO S. V. KULLANDA M.A. MOLINA M.N. SAENKO I.S. YAKUBOVICH Founded by Kirill BABAEV © Russian State University for the Humanities, 2019 Редакционный совет: Х. АЙХНЕР (Вена) / председатель В. БЛАЖЕК (Брно) У. БЭКСТЕР (Анн Арбор) В. Ф. ВЫДРИН (Париж) М. ГЕЛЛ-МАНН (Санта-Фе) Ф. КОРТЛАНДТ (Лейден) А. ЛУБОЦКИЙ (Лейден) Дж. МЭЛЛОРИ (Белфаст) А. Ю. МИЛИТАРЕВ (Москва) Л. ХАЙМАН (Беркли) Редакционная коллегия: В. А. ДЫБО (главный редактор) Г. С. СТАРОСТИН (заместитель главного редактора) Т. А. МИХАЙЛОВА (ответственный секретарь) А. В. ДЫБО С. В. КУЛЛАНДА М. А. МОЛИНА М. Н. САЕНКО И. С. ЯКУБОВИЧ Журнал основан К. В. БАБАЕВЫМ © Российский государственный гуманитарный университет, 2019 Вопросы языкового родства: Международный научный журнал / Рос. гос. гуманитар. ун-т; Рос. акад. наук. Ин-т языкознания; под ред. В. А. Дыбо. ― М., 2019. ― № 17/2. ― x + 84 с. Journal of Language Relationship: International Scientific Periodical / Russian State Uni- versity for the Humanities; Russian Academy of Sciences. -

Tuning Presets in the MOTM

Tuning Presets in the Sequential Prophet X Compiled by Robert Rich, September 2018 Comments for tunings 17-65 derived from the Scala library. Many thanks to Max Magic Microtuner for conversion assistance. R. Rich Notes: All of the presets except for #1 (12 Tone Equal Temperament) can be over-written by sending a tuning in the MTS format (Midi Tuning Standard.) The presets #2-17 match the Prophet 12, P6 and OB6, and began as a selection I made for the Synthesis Technology MOTM 650 Midi-CV module. Actual program numbers within the MTS messages start at #0 for the built-in 12ET, #1-64 for the user tunings. The display shows these as #2-65, with 12ET as #1. I intend these tunings only as an introduction, and I did not research their historical accuracy. For convenience, I used the software’s default 1/1 of C4 (Midi note 60), although this is not the original 1/1 for some of the tunings shown. Some of these tunings come very close to standard 12ET, and some of them are downright wacky, sometimes specific to a particular composer or piece of music. The tunings from 18 to 65 are organized only by alphabet, culled from the Scala library, not in any logical order. 1. 12 Tone Equal Temperament (non-erasable) The default Western tuning, based on the twelfth root of two. Good fourths and fifths, horrible thirds and sixths. 2. Harmonic Series MIDI notes 36-95 reflect harmonics 2 through 60 based on the fundamental of A = 27.5 Hz. -

Teletype - Manual Contents

teletype - manual Contents Introduction 4 Updates 5 v4.0.0 .................................... 5 v3.2.0 .................................... 6 Version 3.1 ................................. 6 Version 3.0 ................................. 7 Version 2.2 ................................. 11 Version 2.1 ................................. 13 Version 2.0 ................................. 15 Quickstart 18 Panel .................................... 18 LIVE mode ................................. 18 EDIT mode ................................. 19 Patterns .................................. 21 Scenes ................................... 22 USB Backup ................................. 23 Commands ................................. 23 Continuing ................................. 25 Keys 26 Global key bindings ............................. 26 Text editing ................................. 26 Live mode .................................. 27 Edit mode .................................. 27 Tracker mode ................................ 28 Preset read mode .............................. 29 Preset write mode .............................. 30 Help mode ................................. 30 1 OPs and MODs 31 Variables .................................. 32 Hardware .................................. 35 Patterns .................................. 40 Control flow ................................. 46 Maths .................................... 52 Metronome ................................. 61 Delay .................................... 62 Stack ................................... -

Compactly Supported One-Cyclic Wavelets Derived from Beta Distributions H

1 Compactly Supported One-cyclic Wavelets Derived from Beta Distributions H. M. de Oliveira, G. A. A. de Araujo´ Resumo—New continuous wavelets of compact support are n t−b introduced, which are related to the beta distribution. They can 1 t − b n 1 @ P ( a ) n( ) = (−1) : (4) be built from probability distributions using ”blur”derivatives. pjaj a pjaj @tn These new wavelets have just one cycle, so they are termed unicycle wavelets. They can be viewed as a soft variety of Haar Now wavelets whose shape is fine-tuned by two parameters a and b. Close expressions for beta wavelets and scale functions as well as @nP ( t−b ) 1 t − b their spectra are derived. Their importance is due to the Central a n (n) n = (−1) n P ( ); (5) Limit Theorem applied for compactly supported signals. 1 @b a a Index Terms—One cycle-wavelets, continuous wavelet, blur so that derivative, beta distribution, central limit theory, compactly 1 Z +1 @nP ( t−b ) CWT (a; b) = f(t) · a dt: supported wavelets. p n (6) jaj −∞ @b If the order of the integral and derivative can be commuted, I. PRELIMINARIES AND BACKGROUND it follows that Avelets are strongly connected with probability dis- tributions. Recently, a new insight into wavelets was W 1 @n Z +1 t − b presented, which applies Max Born reading for the wave- CWT (a; b) = f(t) · P ( )dt: p n (7) function [1] in such a way that an information theory focus jaj @b −∞ a has been achieved [2]. Many continuous wavelets are derived Defining the LPFed signal as the ”blur”signal from a probability density (e.g. -

Partitioning Phylogenetic and Functional Diversity Into Alpha and Beta Components Along an Environmental Gradient in a Mediterra

Journal of Vegetation Science 24 (2013) 877–889 SPECIAL FEATURE: FUNCTIONAL DIVERSITY Partitioning phylogenetic and functional diversity into alpha and beta components along an environmental gradient in a Mediterranean rangeland Maud Bernard-Verdier, Olivier Flores, Marie-Laure Navas & Eric Garnier Keywords Abstract Beta dissimilarity; Calcareous rangelands; Community assembly; Environmental gradient; Questions: To what extent is the functional structure of plant communities Functional traits; Phylogenetic community captured by phylogenetic structure? Are some functional dimensions better rep- structure; Trait phylogenetic signal resented by phylogenetic relationships? In an empirical study, we propose to test the congruence between phylogenetic and functional structure at the alpha and Nomenclature the beta scale along an environmental gradient. Bernard (1996) Location: Causse du Larzac, southern France. Received 1 April 2012 Accepted 12 December 2012 Methods: We measured species abundances and eight key functional traits in Co-ordinating Editor: Francesco de Bello 12 plant communities distributed along a gradient of soil depth and resource availability in a Mediterranean rangeland. A phylogenetic super-tree of the spe- cies was assembled, and after quantifying the degree of phylogenetic signal pres- Bernard-Verdier, M. (corresponding author, ent in each trait, we quantified taxonomic (TD), phylogenetic (PD) and [email protected]): Universite´ functional (FD) diversity both within (alpha scale) and among (beta scale) com- Montpellier 2, Centre d’Ecologie Fonctionnelle munities, taking species abundances into account. We tested for trends in diver- et Evolutive (UMR 5175), 1919 route de Mende, sity along the environmental gradient, and looked for congruence among 34293 Montpellier, France different facets of diversity, both at the alpha and the beta scale. -

TIP 57 Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services

A TREATMENT IMPROVEMENT PROTOCOL Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services TIP 57 A TREATMENT IMPROVEMENT PROTOCOL Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services TIP 57 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Center for Substance Abuse Treatment 1 Choke Cherry Road Rockville, MD 20857 Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services Acknowledgments This publication was produced under contract numbers 270-99-7072, 270-04-7049, and 270 09-0307 by the Knowledge Application Program (KAP), a Joint Venture of The CDM Group, Inc., and JBS International, Inc., for the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Andrea Kopstein, Ph.D., M.P.H., Karl D. White, Ed.D., and Christina Currier served as the Contracting Officer’s Representatives. Disclaimer The views, opinions, and content expressed herein are the views of the consensus panel members and do not necessarily reflect the official position of SAMHSA or HHS. No official support of or endorsement by SAMHSA or HHS for these opinions or for the instruments or resources described are intended or should be inferred. The guidelines presented should not be considered substitutes for individualized client care and treatment decisions. Public Domain Notice All materials appearing in this volume except those taken directly from copyrighted sources are in the public domain and may be reproduced or copied without permission from SAMHSA or the authors. Citation of the source is appreciated. However, this publication may not be reproduced or distributed for a fee without the specific, written authorization of the Office of Communications, SAMHSA, HHS. -

Music Theory Contents

Music theory Contents 1 Music theory 1 1.1 History of music theory ........................................ 1 1.2 Fundamentals of music ........................................ 3 1.2.1 Pitch ............................................. 3 1.2.2 Scales and modes ....................................... 4 1.2.3 Consonance and dissonance .................................. 4 1.2.4 Rhythm ............................................ 5 1.2.5 Chord ............................................. 5 1.2.6 Melody ............................................ 5 1.2.7 Harmony ........................................... 6 1.2.8 Texture ............................................ 6 1.2.9 Timbre ............................................ 6 1.2.10 Expression .......................................... 7 1.2.11 Form or structure ....................................... 7 1.2.12 Performance and style ..................................... 8 1.2.13 Music perception and cognition ................................ 8 1.2.14 Serial composition and set theory ............................... 8 1.2.15 Musical semiotics ....................................... 8 1.3 Music subjects ............................................. 8 1.3.1 Notation ............................................ 8 1.3.2 Mathematics ......................................... 8 1.3.3 Analysis ............................................ 9 1.3.4 Ear training .......................................... 9 1.4 See also ................................................ 9 1.5 Notes ................................................