Oral History Interview with Lowery Stokes Sims, 2010 July 15-22

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Proposal Information Summary: the Ph.D

Graduate Center of the City University of New York | Principal Investigator: Claire Bishop | Grant Reference NumBer: 1811-06406 Proposal Information Summary: The Ph.D. Program in Art History at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York (CUNY) proposes a renewal of funding by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for the project “New Initiatives in Curatorial Training.” We are requesting $650,000 for a five-year renewal that would deepen and formaliZe the program’s long-standing commitment to training future curators and other museum and arts professionals. The project will build on a successful three-year pilot, as well as a four-year renewal grant, that enabled the Ph.D. Program in Art History to strengthen curatorial training in art history, with a particular focus on Modern and Contemporary topics. As a result of the grants, the Ph.D. Program has forged closer links with exhibiting institutions in the city and nearby region through teaching and fellowships; these institutions include El Museo del Barrio, the Hispanic Society, the Newark Museum, MoMA, Dia Center for the Arts, the Morgan Library, the Queens Museum, the Whitney Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It has also enriched the relationship between the Ph.D. Program in Art History and the Graduate Center’s own James Gallery, leading to a series of student-curated exhibitions there. A final Mellon Foundation grant for this initiative is sought to continue addressing the intersection of research and curatorial training, but with two new emphases: (1) to enhance the diversity of curatorial training at the Graduate Center by broadening the curriculum and the curatorial opportunities available for the study of global art. -

Museums, Feminism, and Social Impact Audrey M

State University of New York College at Buffalo - Buffalo State College Digital Commons at Buffalo State Museum Studies Theses History and Social Studies Education 5-2019 Museums, Feminism, and Social Impact Audrey M. Clark State University of New York College at Buffalo - Buffalo State College, [email protected] Advisor Nancy Weekly, Burchfield Penney Art Center Collections Head First Reader Cynthia A. Conides, Ph.D., Associate Professor and Coordinator of the Museum Studies Program Department Chair Andrew D. Nicholls, Ph.D., Chair and Professor of History To learn more about the History and Social Studies Education Department and its educational programs, research, and resources, go to https://history.buffalostate.edu/. Recommended Citation Clark, Audrey M., "Museums, Feminism, and Social Impact" (2019). Museum Studies Theses. 21. https://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/museumstudies_theses/21 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.buffalostate.edu/museumstudies_theses Part of the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons, Museum Studies Commons, and the Women's History Commons I Abstract This paper aims to explore the history of women within the context of the museum institution; a history that has often encouraged collaboration and empowerment of marginalized groups. It will interpret the history of women and museums and the impact on the institution by surveying existing literature on feminism and museums and the biographies of a few notable female curators. As this paper hopes to encourage global thinking, museums from outside the western sphere will be included and emphasized. Specifically, it will look at organizations in the Middle East and that exist in only a digital format. This will lead to an analysis of today’s feminist principles applied specifically to the museum and its link with online platforms. -

Digital Review Copy May Not Be Copied Or Reproduced Without Permission from the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago

DIGITAL REVIEW COPY MAY NOT BE COPIED OR REPRODUCED WITHOUT PERMISSION FROM THE MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART CHICAGO. HOWARDENA PINDELL WHAT REMAINS TO BE SEEN Published by the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago and DelMonico Books•Prestel NAOMI BECKWITH is Marilyn and Larry Fields Curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. VALERIE CASSEL OLIVER is Sydney and Frances Lewis Family Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. ON THE JACKET Front: Untitled #4D (detail), 2009. Mixed media on paper collage; 7 × 10 in. Back: Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, Howardena Pindell from the series Art World, 1980. Gelatin silver print, edition 2/2; 13 3/4 × 10 3/8 in. The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Neil E. Kelley, 2006.867. © Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, All Rights Reserved. Courtesy of Hiram Butler Gallery. Printed in China HOWARDENA PINDELL WHAT REMAINS TO BE SEEN Edited by Naomi Beckwith and Valerie Cassel Oliver Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago DelMonico Books • Prestel Munich London New York CONTENTS 15 DIRECTOR’S FOREWORD Madeleine Grynsztejn 17 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Naomi Beckwith Valerie Cassel Oliver 21 OPENING THOUGHTS Naomi Beckwith Valerie Cassel Oliver 31 CLEARLY SEEN: A CHRONOLOGY Sarah Cowan 53 SYNTHESIS AND INTEGRATION IN THE WORK Lowery Stokes Sims OF HOWARDENA PINDELL, 1972–1992: A (RE) CONSIDERATION 87 BODY OPTICS, OR HOWARDENA PINDELL’S Naomi Beckwith WAYS OF SEEING 109 THE TAO OF ABSTRACTION: Valerie Cassel Oliver PINDELL’S MEDITATIONS ON DRAWING 137 HOWARDENA PINDELL: Charles -

Hughie Lee-Smith Chronology

HUGHIE LEE-SMITH CHRONOLOGY Compiled by Aiden Faust 1915 20 September: Hughie Lee Snuth is born in Eustis, FL, to Luther Snuth and Alice Carroll (Williams) Smith. Alice and child soon return to her parents' home at 14 7 Glen Street in Atlanta, GA. 1919 Alice moves to Cleveland, OH, to pursue a career in music. Hughie stays in the care of his recently widowed grandmother, "Queenie" Victoria Williams. Early 1920s Nicknamed "Little Man" by relatives for his precocious nature, Lee Snuth is allowed few playmates; he begins to fo cus on art. Early subjects include the trains of the Southern Railroad, whose tracks are visible from the Williams backyard. He also copies Old Masters reproductions and Gustave Dore's illustrations of Bible stories. Between the ages of six and ten, Hughie makes annual visits to ills mother's home in Oruo. 1925 Now securely established in Cleveland, Alice brings Queenie and Hughie to live with her. Alice-a gifted singer-recognizes her son's artistic talent and enrolls him in Saturday morning classes at the Cleveland Museum of Art. 1927 Lee Smith advances to Saturday classes at the Cleveland School of Art. He attends Fairmount Junior High and begins running track. 1929 Enrolled at East Technical High School, Lee SnLith runs the 220-yard low hurdles on the track team. Teammates include Jesse Owens and Dave Albritton. 1931 At the close of sophomore year, Lee Smith declares horticulture as his area of academic specialization. But over the summer, he begins drawing seriously again; at the start of his third year at East Tech, he changes his specialization to fine arts. -

Lowery Stokes Sims

Lowery Stokes Sims Guest Curator The US-Mexico Border: Place, Imagination, and Possibility Lowery Stokes Sims, recently named one of the Most Influential Curators by Artsy, is the retired Curator Emerita at the Museum of Arts and Design. She served as executive director then president of The Studio Museum in Harlem and was on the education and curatorial staff of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. A specialist in modern and contemporary art, she is known for her particular expertise in the work of African, Latino, Native and Asian American artists. Sims has published extensively and has lectured nationally and internationally and guest curated numerous exhibitions around the world. She holds a Ph.D. in Art History from the Graduate School of the City University of New York and has received honorary degrees from the Maryland Institute College of Art, Moore College of Art and Design, Parsons School of Design at the New School University, the Atlanta College of Art, and College of New Rochelle and Brown University. She holds a B.A. in Art History from Queens College, City University of New York, and a M.A. in Art History from Johns Hopkins University. Sims has published extensively and her research on the work of the Afro-Cuban Chinese Surrealist artist Wifredo Lam was published by the University of Texas Press in 2002. In 1997, she organized a survey of the work of Richard Pousette-Dart at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Sims has lectured nationally and internationally and guest curated numerous exhibitions, most recently at the National Gallery of Jamaica, Kingston, Jamaica (2004), The Cleveland Museum of Art and the New York Historical Society (2006). -

Press Release

NEWS FROM THE GETTY news.getty.edu | [email protected] DATE: March 26, 2018 MEDIA CONTACT FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Julie Jaskol Getty Communications (310) 440-7607 [email protected] J. PAUL GETTY TRUST ANNOUNCES J. PAUL GETTY MEDAL TO GO TO THELMA GOLDEN, AGNES GUND AND RICHARD SERRA Awards to be presented at a celebratory dinner at the Getty Center in Los Angeles September 24, 2018 LOS ANGELES – The J. Paul Getty Trust announced today it will present the annual J. Paul Getty Medal to Thelma Golden, director and chief curator of the Studio Museum in Harlem; Agnes Gund, president emerita of the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA); and sculptor Richard Serra. Established in 2013 by the trustees of the J. Paul Getty Trust, the J. Paul Getty Medal has been awarded to eight individuals to honor their extraordinary contributions to the practice, understanding and support of the arts. “The Getty Medal embodies and promotes excellence in the fields in which we work,” said Maria Hummer-Tuttle, chair, J. Paul Getty Board of Trustees. “We are honored to present the medal this year to three leaders and creative forces within the visual arts.” James Cuno, president and CEO of the J. Paul Getty Trust, said of Thelma Golden, “Thelma is a creative and influential leader in our field, who has led the growth of the Studio Thelma Golden photographed by Julie Skarratt Museum, making it one of our nation’s most The J. Paul Getty Trust 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 403 Tel: 310 440 7360 www.getty.edu Communications Department Los Angeles, CA 90049-1681 Fax 310 440 7722 dynamic visual arts institutions, inspiring to professionals and public alike. -

Grant Application Form (Mini Or Regular Grant)

New Mexico Humanities Council Grant Application Form (Mini or Regular Grant) NMHC Use Only Total Amount Requested: 12000.00 Total Amount of Matching Contribution: 104905.00 Application Number: 2563 Total Challenge Grant Amount: 0.00 Application Deadline: 2 Oct 2017, 5:01pm MT Award: PDF Generated: 5 Oct 2017, 6:39pm MT Project Title: The US-Mexico Border: Place Imagination, and Possibility Project Description: 516 ARTS, in partnership with the Albuquerque Museum, presents ?The US-Mexico Border: Place, Imagination, and Possibility,? a group exhibition of work by over 40 designers and artists working along the U.S./Mexico border who engage with intersections of culture that have developed in the region, while considering the welfare and wellbeing of migrants and citizens who live there. These contemporary artists explore the border as a physical reality (place), as subject (imagination), and as a site for production and forward-thinking solutions (possibility). While the selection largely focuses on work executed in the last two decades, it includes objects by Chicano artists in California who converged in the 1970s-1980s to address border issues in their work. The inclusion of artists from various disciplines, including design, architecture, sculpture, painting and photography, reflects the ways in which contemporary artists and designers cross disciplinary borders. The main exhibition in Albuquerque, hosted by 516 ARTS, expanded into a second site at the Albuquerque Museum due to the volume of work. Accompanying interdisciplinary programs around the city include partnerships with: Albuquerque Museum, UNM Art Museum, Outpost Performance Space, Guild Cinema, Sanitary Tortilla Factory, Santa Fe Dreamers Project, UNM Dream Team, New Mexico Immigration Law Center and National Hispanic Cultural Center. -

Announcement

Announcement 29 articles, 2016-05-15 00:01 1 Remembering Martin Friedman (1925–2016) — Magazine — (1.03/2) Walker Art Center Martin Friedman, the director of the Walker Art Center from 1961 to 1990, passed away May 9, 2016, at age 90... 2016-05-14 11:31 15KB www.walkerart.org 2 2016 Cannes Film Festival: Chopard Toasts Green Carpet Collection The yacht party, hosted by Colin and Livia Firth, drew Harvey Weinstein and Calu Rivero. (0.01/2) 2016-05-14 17:56 2KB wwd.com 3 joão teixeira sustainable surf design with amorim cork following thorough development and material explorations, a surfboard of expanded cork and flax fiber with wooden fins was realized. 2016-05-14 21:30 1KB www.designboom.com 4 kikkawa architects opens house in atsugi to the japanese countryside kikkawa architects have re-built a contemporary farmhouse in the countryside. 2016-05-14 18:15 1KB www.designboom.com 5 Pharrell on Adidas Collab, Street Style and the Importance of Staying Curious The multihyphenate artist talked about his collaboration with Adidas Originals and where he finds inspiration for everything from style to music. 2016-05-14 17:17 4KB wwd.com 6 Affable Experimentation: Steve Lehman Octet at the Walker To spark discussion, the Walker invites Twin Cities artists and critics to write overnight reviews of our performances. The ongoing Re:View series shares a diverse array of independent voices and opi... 2016-05-14 18:23 935Bytes blogs.walkerart.org 7 klaas kuiken's uses a lost-foam casting technique to mould EPS collection the 'EPS' collection created by klaas kuiken consists of wood stoves and clocks which all use a lost-foam coating technique. -

The Center in 2011

Mission The Center for Art in Wood, formerly the Wood Turning Center, is an arts and educational institution whose mission is leading the growth, awareness, appreciation and promotion of artists and their creation and design of art in wood and wood in combination with other materials. May 2011 Issue: 17 The Center in 2011 - In This Issue New Location and New Name It's In The Name Recent Awards Dear Andrew, Come to the Center FROM THE CO-FOUNDER AND EXECUTIVE ITE 2011 DIRECTOR Museum Store Albert LeCoff Challenge VIII: Call for Artists New Faces at the Center Visit the Center and See Our Inventory in the Museum Store Jerry & Deborah Kermode NEW LOCATION Wood Turnings available price range from After 11 years at our location at 501 Vine Street and, as part $120 - $380 of the new Strategic Business Plan, the Center committed itself to moving to a more centrally located facility in heart of Philadelphia's Old City Arts District. In 2010, the Board, staff and constituents collectively began planning for the move during which time many of you supported the design and engineering work on the building. Initially we anticipated moving to a building adjacent to the John Grass Wood Turning Company on North 2nd Street. Unfortunately, after careful study, renovations to the building proved too expensive. Serendipitously at precisely the same time, a building on North 3rd and Quarry Streets became available. Rock Paper Scissors lines of fun paper products. rd The Center's new location is 141 N. 3 Street, between Arch Coaster pack of 12 price and Race Streets. -

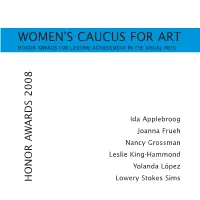

Women's Caucus For

30866_RainbowGraphics:WCA-LAAvers5 2/4/08 2:58 PM Page 1 WOMEN’S CAUCUS FOR ART HONOR AWARDS FOR LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT IN THE VISUAL ARTS Ida Applebroog Joanna Frueh Nancy Grossman Leslie King-Hammond Yolanda López Lowery Stokes Sims HONOR AWARDS 2008 30866_RainbowGraphics:WCA-LAAvers5 2/4/08 2:58 PM Page 2 30866_RainbowGraphics:WCA-LAAvers5 2/4/08 2:58 PM Page 3 2008 National Lifetime Achievement Awards Saturday, February 23rd Westin City Center Hotel, Dallas, Texas Introduction Jennifer Colby WCA National Board President, 2006–08 Presentation of Awards Ida Applebroog Essay by Helen Molesworth. Presentation by E. Luanne McKinnon Joanna Frueh Essay and Presentation by Tanya Augsburg Nancy Grossman Essay by Carey Lovelace. Presentation by Sungmi Lee Leslie King-Hammond Essay and Presentation by Elizabeth Turner Yolanda López Essay by Cary Cordova. Presentation by Moira Roth Lowery Stokes Sims Essay and Presentation by Ann Gibson President’s Awards Santa Contreras Barraza Joan Davidow Tey Marianna Nunn Presentation by Jennifer Colby 30866_RainbowGraphics:WCA-LAAvers5 2/4/08 2:58 PM Page 4 Foreword and Acknowledgements With the 2008 ceremony, we recognize the Carey Lovelace’s essay helps us understand more about achievements of six women who have contributed so Nancy Grossman’s visceral aesthetic. Sungmi Lee, a impressively to feminism and the visual arts: Ida Brooklyn-based artist, will present Nancy Grossman with Applebroog, Joanna Frueh, Nancy Grossman, Yolanda the award. Elizabeth Turner, Professor at the University of López, Leslie King-Hammond, and Lowery Stokes Sims. Virginia, gives an embracing portrait of Leslie King- Each of this year’s honorees has expanded our Hammond and her accomplishments in her essay and will understanding of art and our world. -

Jonathan Weinberg's CV

Jonathan Weinberg Artist/Art Historian www.jonathanweinberg.com Current Position: Lecturer, Graduate Printmaking Department and Liberal Arts Program Rhode Island School of Design Critic, Yale School of Art EDUCATION: Art History Ph. D., Dept. of Fine Arts, Harvard University, 1990. B. A., Yale College, 1978. Painting and Design Cornell Program in Architectural Illustration, Rome, Italy, 1982 Hunter College, CUNY, New York, New York--Graduate Program in Painting, 1978-79 New York Studio School of Painting and Sculpture, New York, New York, Summer, 1977 Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Skowhegan, Maine, Summer, 1976 SUBJECT OF DISSERTATION: “Speaking for Vice: Homosexuality in the art of Charles Demuth, Marsden Hartley and the Early American Avant-Garde.” FELLOWSHIPS AND RESIDENCIES: Creative Capital, Grant to write a History of the Art and Subcultures of the Piers along the West Side Highway in New York City, 2009 Artist-in-Residence, Addison Museum of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, Fall 2006. J. Clawson Mills Art History Fellowship, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2005- 2006. Sterling and Francine Clark Institute Fellowship, 2004-2005. John Simon Guggenheim, 2002 (Deferred until July 2003-June 2004) Getty Scholar and Artist in Residence 2002-2003 Senior Fellow, Vera List Center for Art and Politics, New School 2002-2003 Artist-in-Residence, St. Michael’s College, Colchester, VT, Summer 2000. Griswold Grant, Yale University, 2000 Weinberg c.v. December 13, 2015 Hilles Publication Grant, Yale University, 1999 Faculty Fellowship, Yale University, 1997-98 Griswold Grant, Yale University, 1995-96. Morse Fellowship, Yale University, 1994-95. Enders Research Grant, Yale University, 1990-91. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE: Critic, School of Art, Yale University 2009- Lecturer, Rhode Island School of Design, 2009- 2012-13 Visiting Associate Professor, History of Art and Architecture Brown University, Providence, RI. -

Guide to the Papers of African American Artists and Related

Guide to the Papers of January 2020 African American Artists and Related Resources 2 What We do Above: Titus Kaphar in his 11th Avenue Studio, New York City, 2008. Photograph by Jerry L. Thompson. Jerry L. Thompson papers. Cover: Chakaia Booker installing Foci (2010) at Storm King Art Center, Mountainville, New York, 2010. Photograph by Jerry L. Thompson. Jerry L. Thompson papers. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS 05 Our History 06 What We Do 10 A Culture of Access 11 Archives in the World 12 Why the Archives of American Art? 15 Recent Acquisition Highlights 17 Guide to African American Collections 48 Additional Papers of African American Artists 56 Oral History Interviews 60 Related Resources 72 Administration and Staf 4 HISTORY AND ABOUT The Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art enlivens the extraordinary human stories behind the United States’ most signifcant art and artists. It is the world’s preeminent resource dedicated to collecting and preserving the papers and primary records of the visual arts in the United States. Constantly growing in range and depth, and ever increasing in its accessibility, it is a vibrant, unparalleled, and essential resource for the appreciation, enjoyment, and understanding of art in America. 5 Our History In a 1954 letter from then director of the Detroit Institute of Arts Edgar P. Richardson to Lawrence A. Fleischman, Richardson poses a question: “Do you realize what a big thing you have done in starting the Archives [of American Art]? I know you do. But do you? It is enormous in its implications; enormous!” Richardson and Fleischman, a Detroit businessman and an active young collector, had founded the Archives earlier that year.