Museums, Feminism, and Social Impact Audrey M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weaverswaver00stocrich.Pdf

University of California Berkeley Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Fiber Arts Oral History Series Kay Sekimachi THE WEAVER'S WEAVER: EXPLORATIONS IN MULTIPLE LAYERS AND THREE-DIMENSIONAL FIBER ART With an Introduction by Signe Mayfield Interviews Conducted by Harriet Nathan in 1993 Copyright 1996 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the Nation. Oral history is a modern research technique involving an interviewee and an informed interviewer in spontaneous conversation. The taped record is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The resulting manuscript is typed in final form, indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ************************************ All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Kay Sekimachi dated April 16, 1995. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

PUBLIC SCULPTURE LOCATIONS Introduction to the PHOTOGRAPHY: 17 Daniel Portnoy PUBLIC Public Sculpture Collection Sid Hoeltzell SCULPTURE 18

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 VIRGINIO FERRARI RAFAEL CONSUEGRA UNKNOWN ARTIST DALE CHIHULY THERMAN STATOM WILLIAM DICKEY KING JEAN CLAUDE RIGAUD b. 1937, Verona, Italy b. 1941, Havana, Cuba Bust of José Martí, not dated b. 1941, Tacoma, Washington b. 1953, United States b. 1925, Jacksonville, Florida b. 1945, Haiti Lives and works in Chicago, Illinois Lives and works in Miami, Florida bronze Persian and Horn Chandelier, 2005 Creation Ladder, 1992 Lives and works in East Hampton, New York Lives and works in Miami, Florida Unity, not dated Quito, not dated Collection of the University of Miami glass glass on metal base Up There, ca. 1971 Composition in Circumference, ca. 1981 bronze steel and paint Location: Casa Bacardi Collection of the University of Miami Gift of Carol and Richard S. Fine aluminum steel and paint Collection of the University of Miami Collection of the University of Miami Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alfred Camner Location: Gumenick Lobby, Newman Alumni Center Collection of the Lowe Art Museum, Collection of the Lowe Art Museum, Location: Casa Bacardi Location: Casa Bacardi Location: Gumenick Lobby, Newman Alumni Center University of Miami University of Miami Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Blake King, 2004.20 Gift of Dr. Maurice Rich, 2003.14 Location: Wellness Center Location: Pentland Tower 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 JANE WASHBURN LEONARDO NIERMAN RALPH HURST LEONARDO NIERMAN LEOPOLDO RICHTER LINDA HOWARD JOEL PERLMAN b. United States b. 1932, Mexico City, Mexico b. 1918, Decatur, Indiana b. 1932, Mexico City, Mexico b. 1896, Großauheim, Germany b. 1934, Evanston, Illinois b. -

THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM of ART ANNUAL REPORT 2002 1 0-Cover.P65 the CLEVELAND MUSEUM of ART

ANNUAL REPORT 2002 THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART REPORT 2002 ANNUAL 0-Cover.p65 1 6/10/2003, 4:08 PM THE CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART ANNUAL REPORT 2002 1-Welcome-A.p65 1 6/10/2003, 4:16 PM Feathered Panel. Peru, The Cleveland Narrative: Gregory Photography credits: Brichford: pp. 7 (left, Far South Coast, Pampa Museum of Art M. Donley Works of art in the both), 9 (top), 11 Ocoña; AD 600–900; 11150 East Boulevard Editing: Barbara J. collection were photo- (bottom), 34 (left), 39 Cleveland, Ohio Bradley and graphed by museum (top), 61, 63, 64, 68, Papagayo macaw feathers 44106–1797 photographers 79, 88 (left), 92; knotted onto string and Kathleen Mills Copyright © 2003 Howard Agriesti and Rodney L. Brown: p. stitched to cotton plain- Design: Thomas H. Gary Kirchenbauer 82 (left) © 2002; Philip The Cleveland Barnard III weave cloth, camelid fiber Museum of Art and are copyright Brutz: pp. 9 (left), 88 Production: Charles by the Cleveland (top), 89 (all), 96; plain-weave upper tape; All rights reserved. 81.3 x 223.5 cm; Andrew R. Szabla Museum of Art. The Gregory M. Donley: No portion of this works of art them- front cover, pp. 4, 6 and Martha Holden Jennings publication may be Printing: Great Lakes Lithograph selves may also be (both), 7 (bottom), 8 Fund 2002.93 reproduced in any protected by copy- (bottom), 13 (both), form whatsoever The type is Adobe Front cover and frontispiece: right in the United 31, 32, 34 (bottom), 36 without the prior Palatino and States of America or (bottom), 41, 45 (top), As the sun went down, the written permission Bitstream Futura abroad and may not 60, 62, 71, 77, 83 (left), lights came up: on of the Cleveland adapted for this be reproduced in any 85 (right, center), 91; September 11, the facade Museum of Art. -

Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America,” an Intergenerational Exhibition of Works from Thirty-Seven Artists, Conceived by Curator Okwui Enwezor

NEW MUSEUM PRESENTS “GRIEF AND GRIEVANCE: ART AND MOURNING IN AMERICA,” AN INTERGENERATIONAL EXHIBITION OF WORKS FROM THIRTY-SEVEN ARTISTS, CONCEIVED BY CURATOR OKWUI ENWEZOR Exhibition Brings Together Works that Address Black Grief as a National Emergency in the Face of a Politically Orchestrated White Grievance New York, NY...The New Museum is proud to present “Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America,” an exhibition originally conceived by Okwui Enwezor (1963-2019) for the New Museum, and presented with curatorial support from advisors Naomi Beckwith, Massimiliano Gioni, Glenn Ligon, and Mark Nash. On view from February 17 to June 6, 2021, “Grief and Grievance” is an intergenerational exhibition bringing together thirty-seven artists working in a variety of mediums who have addressed the concept of mourning, commemoration, and loss as a direct response to the national emergency of racist violence experienced by Black communities across America. The exhibition further considers the intertwined phenomena of Black grief and a politically orchestrated white grievance, as each structures and defines contemporary American social and political life. Included in “Grief and Grievance” are works encompassing video, painting, sculpture, installation, photography, sound, and performance made in the last decade, along with several key historical works and a series of new commissions created in response to the concept of the exhibition. The artists on view will include: Terry Adkins, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Kevin Beasley, Dawoud Bey, Mark -

Download NARM Member List

Huntsville, The Huntsville Museum of Art, 256-535-4350 Los Angeles, Chinese American Museum, 213-485-8567 North American Reciprocal Mobile, Alabama Contemporary Art Center Los Angeles, Craft Contemporary, 323-937-4230 Museum (NARM) Mobile, Mobile Museum of Art, 251-208-5200 Los Angeles, GRAMMY Museum, 213-765-6800 Association® Members Montgomery, Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, 334-240-4333 Los Angeles, Holocaust Museum LA, 323-651-3704 Spring 2021 Northport, Kentuck Museum, 205-758-1257 Los Angeles, Japanese American National Museum*, 213-625-0414 Talladega, Jemison Carnegie Heritage Hall Museum and Arts Center, 256-761-1364 Los Angeles, LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes, 888-488-8083 Alaska Los Angeles, Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions, 323-957-1777 This list is updated quarterly in mid-December, mid-March, mid-June and Haines, Sheldon Museum and Cultural Center, 907-766-2366 Los Angeles, Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA), Los Angeles, 213-621-1794 mid-September even though updates to the roster of NARM member Kodiak, The Kodiak History Museum, 907-486-5920 Los Angeles, Skirball Cultural Center*, 310-440-4500 organizations occur more frequently. For the most current information Palmer, Palmer Museum of History and Art, 907-746-7668 Los Gatos, New Museum Los Gatos (NUMU), 408-354-2646 search the NARM map on our website at narmassociation.org Valdez, Valdez Museum & Historical Archive, 907-835-2764 McClellan, Aerospace Museum of California, 916-564-3437 Arizona Modesto, Great Valley Museum, 209-575-6196 Members from one of the North American -

Aliza Shvarts Cv

A.I.R. ALIZA SHVARTS CV www.alizashvarts.com SOLO AND TWO PERSON EXHIBITIONS 2018 Off Scene, Artspace, New Haven, CT 2016 Aliza Shvarts, Kevin Kavanagh Gallery, Dublin, Ireland 2010 Knowing You Want It, UCLA Royce Hall, Los Angeles, CA SELECTED GROUP EXHIBITIONS 2019 Study Session: Aliza Shvarts, Ayanna Dozier, and Narcissister, The Whitney Museum, NYC 2019 In Practice: Other Objects. SculptureCenter, Long Island City, NY th 2018 ANTI, 6 Athens Biennale. Athens, Greece 2018 A new job to unwork at, Participant Inc, NYC 2018 Aliza Shvarts, Patty Chang & David Kelley. Marathon Screenings, Los Angeles, CA. 2018 International Festival of Arts&Ideas, Public art commission. New Haven, CT 2017 (No) Coma Cuento, Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia 2017 Aliza Shvarts and Devin Kenny, Video Artists Working Group, Artists Space, NYC 2017 Goldman Club (with Emanuel Almborg), Dotory, Brooklyn, NY 2016 Situational Diagram: Exhibition Walkthrough, Lévy Gorvy Gallery, NYC 2016 SALT Magazine and Montez Press present, Mathew Gallery, NYC 2016 eX-céntrico: dissidence, sovereignties, performance, The Hemispheric Institute, Santiago, Chile 2016 Subject to capital, Abrons Arts Center, NYC 2015 Soap Box Session: Directing Action, ]performance s p a c e[ London, England. 2015 Learning to Speak in a Future Tense, Abrons Arts Center, NYC 2015 The Magic Flute (with Vaginal Davis), 80WSE Gallery. NYC 2015 On Sabotage (screening), South London Gallery, London GRANTS AND AWARDS 2019 A.I.R Artist Fellowship, A.I.R Gallery -

Chryssa B. 1933, Athens D. 2013, Athens New York Times 1975–78

Chryssa b. 1933, Athens d. 2013, Athens New York Times 1975–78 Oil and graphite on canvas Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Gift, Michael Bennett 80.2717 Chryssa began making stamped paintings based on the New York Times in 1958 and continued to do so into the 1970s. To create these works, she had rubber stamps produced based on portions of the newspaper before, as she described it, covering “the entire area [of a canvas] with a fragment repeated precisely.” Over time Chryssa’s treatment of the motif became increasingly abstract, as she more strictly adhered to a gridded composition and selected sections of newsprint with type too small to be legibly rendered in rubber. By deemphasizing the content and format of the newspaper, she redirected focus to the tension between mechanized reproduction and her careful process of stamping by hand. Jacob El Hanani b. 1947, Casablanca Untitled #171 1976–77 Ink and acrylic on canvas Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, Gift, Mr. and Mrs. George M. Jaffin 77.2291 With its dense profusion of finely drawn lines, Jacob El Hanani’s Untitled #171 is a feat of physical endurance, patience, and precision. As the artist said, “It is a personal challenge to bring drawing to the extreme and see how far my eyes and fingers can go.” Rather than approach this effort as an end unto itself, El Hanani has often related it to Jewish traditions of handwriting religious texts—a parallel suggesting a desire to transcend the self through a devotional level of discipline. This aspiration is given form in the way the short, variously weighted lines lose their discreteness from afar and blend into a vaporous whole. -

Alice Neel/Erastus Salisbury Field

Painting the People Alice Neel/Erastus Salisbury Field Fig. 1: Erastus Salisbury Field (1805–1900) Fig. 2: Erastus Salisbury Field (1805–1900) Julius Norton, ca. 1840 Sarah Elizabeth Ball, ca. 1838 Oil on canvas, 35 x 29 inches Oil on canvas, 35⅛ x 29¼ inches Bennington Museum, Bequest of Mrs. Harold C. Payson (Dorothy Norton) Mount Holyoke College Art Museum, South Hadley, Massachusetts Photograph by Petegorsky/Gipe by Jamie Franklin rastus Salisbury Field (1805–1900) and Alice Neel (1900–1984) were masters of the portrait within their respective periods and cultural settings. Though separated by a hundred years and working in distinct styles and contexts, the portraits painted by Field, one of America’s best known nineteenth-century itinerant artists, and Neel, one of the most acclaimed portrait painters of the twentieth century, have a remarkable resonance with one another. Alice Neel/Erastus Salisbury Field: Painting the People, an exhibition at the Bennington Museum in Vermont, examines the visual, historic and conceptual relationships between the paintings of these two seemingly disparate artists. Critics, curators, biographers, friends of the artist, and the artist herself, have referenced the relationship between “folk” or “primitive” painting and Neel’s portraits. However, this is the first exhibition to examine this facet of Neel’s work directly. By looking closely at Field’s and Neel’s political, social, and artistic milieus and the subjects depicted in their portraits, the exhibition seeks to reexamine the relationship between modernism and its romantic notions of the “folk,” while providing us with a more nuanced understanding of these important artists and their work. -

Curator of Native American Art DEPARTMENT: Curatorial SUPERVISOR: Chief Curator DIRECT REPORTS: None LAST REVISION DATE: August 2020

POSITION DESCRIPTION POSITION TITLE: Curator of Native American Art DEPARTMENT: Curatorial SUPERVISOR: Chief Curator DIRECT REPORTS: none LAST REVISION DATE: August 2020 The Montclair Art Museum is conducting a search to fill a three-year position of Curator of Native American Art. Funded by the Luce Foundation, the position offers an exciting opportunity for the Curator to work with the Museum’s renowned collection of Native art of North America. Overview The Montclair Art Museum (MAM) is currently accepting applications for a three- year, grant funded position of Curator of Native American Art. The Museum’s goal is to engage in further fundraising to establish this position as permanent. The selected hire will have a unique opportunity to make a meaningful impact on the presentation of MAM’s renowned collection of Native art of North America in its dedicated Rand Gallery and throughout the Museum more broadly. The Curator will work to achieve key goals of engaging current, innovative ideas around the representation of Indigenous communities and art museum collections and exhibitions, via collaborative approaches. Throughout the three- year period, the Curator will have access to an eight member Advisory Board of leading Native and non-Native scholars and artists, as well as MAM’s Chief Curator, all of whom will offer ideas and perspectives for consideration in developing the Museum’s Native American programs. The Curator will oversee the presentation of the Fall 2021 incoming traveling exhibition, Color Riot!, from the Heard Museum, featuring Navajo textiles from c. 1860 to 2018. Additional projects will include curating a site-specific artistic intervention opening in early 2022, and will culminate in September 2023 with a new installation of the Museum’s Native American collections in the Rand Gallery. -

Edith Halpert & Her Artists

Telling Stories: Edith Halpert & Her Artists October 9 – December 18, 2020 Charles Sheeler (1883-1965), Home Sweet Home, 1931, conte crayon and watercolor on paper, 11 x 9 in. For Edith Halpert, no passion was merely a hobby. Inspired by the collections of artists like Elie Nadelman, Robert Laurent, and Hamilton Easter Field, Halpert’s interest in American folk art quickly became a part of the Downtown Gallery’s ethos. From the start, she furnished the gallery with folk art to highlight the “Americanness” of her artists. Halpert stated, “the fascinating thing is that folk art pulls in cultures from all over the world which we have utilized and made our own…the fascinating thing about America is that it’s the greatest conglomeration” (AAA interview, p. 172). Halpert shared her love of folk art with Charles Sheeler and curator Holger Cahill, who was the original owner of this watercolor, Home Sweet Home, 1931. The Sheelers filled their home with early American rugs and Shaker furniture, some of which are depicted in Home Sweet Home, and helped Halpert find a saltbox summer home nearby, which she also filled with folk art. As Halpert recalled years later, Sheeler joined her on trips to Bennington cemetery to look at tombstones she considered to be the “first folk art”: I used to die. I’d go to the Bennington Cemetery. Everybody thought I was a queer duck. People used to look at me. That didn’t bother me. I went to that goddamn cemetery, and I went to Bennington at least four times every summer…I’d go into that cemetery and go over those tombstones, and it’s great sculpture. -

Oral History Interview with Edith Gregor Halpert, 1965 Jan. 20

Oral history interview with Edith Gregor Halpert, 1965 Jan. 20 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Interview HP: HARLAN PHILLIPS EH: EDITH HALPERT HP: We're in business. EH: I have to get all those papers? HP: Let me turn her off. EH: Let met get a package of cigarettes, incidentally. [Looking over papers, correspondence, etc.] This was the same year, 1936. I quit in September. I was in Newtown; let's see, it must have been July. In those days, I had a four months vacation. It was before that. Well, in any event, sometime probably in late May, or early in June, Holger Cahill and Dorothy Miller, his wife -- they were married then, I think -- came to see me. She has a house. She inherited a house near Pittsfield, Massachusetts, and on the way back they stopped off and very excited that through Audrey McMahon he was offered a job to take charge of the WPA in Washington. He was quite scared because he had never been in charge of anything. He worked by himself as a PR for the Newark Museum for many years, and that's all he did. He sent out publicity releases that Dana gave him, or Miss Winsor, you know, told him what to say, and he was very good at it. He also got the press. -

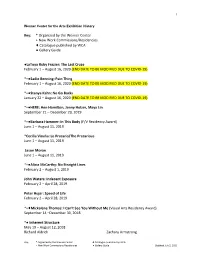

Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center + New Work Commissions/Residencies ♦ Catalogue Published by WCA ● Gallery Guide

1 Wexner Center for the Arts Exhibition History Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center + New Work Commissions/Residencies ♦ Catalogue published by WCA ● Gallery Guide ●LaToya Ruby Frazier: The Last Cruze February 1 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●Sadie Benning: Pain Thing February 1 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●Stanya Kahn: No Go Backs January 22 – August 16, 2020 (END DATE TO BE MODIFIED DUE TO COVID-19) *+●HERE: Ann Hamilton, Jenny Holzer, Maya Lin September 21 – December 29, 2019 *+●Barbara Hammer: In This Body (F/V Residency Award) June 1 – August 11, 2019 *Cecilia Vicuña: Lo Precario/The Precarious June 1 – August 11, 2019 Jason Moran June 1 – August 11, 2019 *+●Alicia McCarthy: No Straight Lines February 2 – August 1, 2019 John Waters: Indecent Exposure February 2 – April 28, 2019 Peter Hujar: Speed of Life February 2 – April 28, 2019 *+♦Mickalene Thomas: I Can’t See You Without Me (Visual Arts Residency Award) September 14 –December 30, 2018 *● Inherent Structure May 19 – August 12, 2018 Richard Aldrich Zachary Armstrong Key: * Organized by the Wexner Center ♦ Catalogue published by WCA + New Work Commissions/Residencies ● Gallery Guide Updated July 2, 2020 2 Kevin Beasley Sam Moyer Sam Gilliam Angel Otero Channing Hansen Laura Owens Arturo Herrera Ruth Root Eric N. Mack Thomas Scheibitz Rebecca Morris Amy Sillman Carrie Moyer Stanley Whitney *+●Anita Witek: Clip February 3-May 6, 2018 *●William Kentridge: The Refusal of Time February 3-April 15, 2018 All of Everything: Todd Oldham Fashion February 3-April 15, 2018 Cindy Sherman: Imitation of Life September 16-December 31, 2017 *+●Gray Matters May 20, 2017–July 30 2017 Tauba Auerbach Cristina Iglesias Erin Shirreff Carol Bove Jennie C.