Oral History Project: Willie Cole

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry

0/-*/&4637&: *ODPMMBCPSBUJPOXJUI6OHMVFJU XFIBWFTFUVQBTVSWFZ POMZUFORVFTUJPOT UP MFBSONPSFBCPVUIPXPQFOBDDFTTFCPPLTBSFEJTDPWFSFEBOEVTFE 8FSFBMMZWBMVFZPVSQBSUJDJQBUJPOQMFBTFUBLFQBSU $-*$,)&3& "OFMFDUSPOJDWFSTJPOPGUIJTCPPLJTGSFFMZBWBJMBCMF UIBOLTUP UIFTVQQPSUPGMJCSBSJFTXPSLJOHXJUI,OPXMFEHF6OMBUDIFE ,6JTBDPMMBCPSBUJWFJOJUJBUJWFEFTJHOFEUPNBLFIJHIRVBMJUZ CPPLT0QFO"DDFTTGPSUIFQVCMJDHPPE The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry The Black Arts Enterprise and the Production of African American Poetry Howard Rambsy II The University of Michigan Press • Ann Arbor First paperback edition 2013 Copyright © by the University of Michigan 2011 All rights reserved Published in the United States of America by The University of Michigan Press Manufactured in the United States of America c Printed on acid-free paper 2016 2015 2014 2013 5432 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. A CIP catalog record for this book is available from the British Library. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rambsy, Howard. The black arts enterprise and the production of African American poetry / Howard Rambsy, II. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-472-11733-8 (cloth : acid-free paper) 1. American poetry—African American authors—History and criticism. 2. Poetry—Publishing—United States—History—20th century. 3. African Americans—Intellectual life—20th century. 4. African Americans in literature. I. Title. PS310.N4R35 2011 811'.509896073—dc22 2010043190 ISBN 978-0-472-03568-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-472-12005-5 (e-book) Cover illustrations: photos of writers (1) Haki Madhubuti and (2) Askia M. Touré, Mari Evans, and Kalamu ya Salaam by Eugene B. Redmond; other images from Shutterstock.com: jazz player by Ian Tragen; African mask by Michael Wesemann; fist by Brad Collett. -

Must Not Be Slavery

The “Spirit of Saratoga” must not be slavery Response to the repulsive wall of “lawn jockeys” that both glorify slavery and erase the history of Black jockeys, currently installed at the National Museum of Racing and Hall of Fame. This is not an act of vandalism. It is a work of public art and an act of applied art criticism. This work of protest art is in solidarity with the Art Action movement and the belief that art is essential to democracy We Reject the whitewashing of Saratoga’s history. We Reject the whitewashing of our national history. This nation was founded on slavery. So was the modern sport of Thoroughbred racing. You insult us and degrade the godfathers of the sport by perpetuating, profiting from and celebrating the flagrant symbol of servitude and slavery that is now called the “lawn jockey.” Just like the confederate flag, the “lawn jockey” is a celebrated relic of the antebellum era. The evolution of the hitching post (later renamed “lawn jockey”) follows the historical national trend of racist imagery and perpetuated stereotypes about Black Americans. This iconography is not unique, and the evidence can be found in everything from postcards, napkin holders, toothpaste, key racks, cigarette lighters, tobacco jars, syrup pitchers and doorstops, to name a fraction of the products designed to maintain the ideology of slavery. The original Jockeys were born into slavery or were the sons of slaves. From its inception in the early 19th century, African-American jockeys ruled the sport of organized Thoroughbred racing for almost a century. Isaac Murphy, the greatest American jockey of all time, was the son of a former slave. -

A Collection Analysis of the African-American Poetry Holdings in the De Grummond Collection Sarah J

SLIS Connecting Volume 2 | Issue 1 Article 9 2013 A Collection Analysis of the African-American Poetry Holdings in the de Grummond Collection Sarah J. Heidelberg Follow this and additional works at: http://aquila.usm.edu/slisconnecting Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Heidelberg, Sarah J. (2013) "A Collection Analysis of the African-American Poetry Holdings in the de Grummond Collection," SLIS Connecting: Vol. 2: Iss. 1, Article 9. DOI: 10.18785/slis.0201.09 Available at: http://aquila.usm.edu/slisconnecting/vol2/iss1/9 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in SLIS Connecting by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Collection Analysis of the African‐American Poetry Holdings in the de Grummond Collection By Sarah J. Heidelberg Master’s Research Project, November 2010 Performance poetry is part of the new black poetry. Readers: Dr. M.J. Norton This includes spoken word and slam. It has been said Dr. Teresa S. Welsh that the introduction of slam poetry to children can “salvage” an almost broken “relationship with poetry” (Boudreau, 2009, 1). This is because slam Introduction poetry makes a poets’ art more palatable for the Poetry is beneficial for both children and adults; senses and draws people to poetry (Jones, 2003, 17). however, many believe it offers more benefit to Even if the poetry that is spoken at these slams is children (Vardell, 2006, 36). The reading of poetry sometimes not as developed or polished as it would correlates with literacy attainment (Maynard, 2005; be hoped (Jones, 2003, 23). -

Album Covers Through Jazz

SantiagoAlbum LaRochelle Covers Through Jazz Album covers are an essential part to music as nowadays almost any project or single alike will be accompanied by album artwork or some form of artistic direction. This is the reality we live with in today’s digital age but in the age of vinyl this artwork held even more power as the consumer would not only own a physical copy of the music but a 12’’ x 12’’ print of the artwork as well. In the 40’s vinyl was sold in brown paper sleeves with the artists’ name printed in black type. The implementation of artwork on these vinyl encasings coincided with years of progress to be made in the genre as a whole, creating a marriage between the two mediums that is visible in the fact that many of the most acclaimed jazz albums are considered to have the greatest album covers visually as well. One is not responsible for the other but rather, they each amplify and highlight each other, both aspects playing a role in the artistic, musical, and historical success of the album. From Capitol Records’ first artistic director, Alex Steinweiss, and his predecessor S. Neil Fujita, to all artists to be recruited by Blue Note Records’ founder, Alfred Lion, these artists laid the groundwork for the role art plays in music today. Time Out Sadamitsu "S. Neil" Fujita Recorded June 1959 Columbia Records Born in Hawaii to japanese immigrants, Fujita began studying art Dave Brubeck- piano Paul Desmond- alto sax at an early age through his boarding school. -

![Biography [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7532/biography-pdf-547532.webp)

Biography [PDF]

NICELLE BEAUCHENE GALLERY RICHARD BOSMAN (b. 1944, Madras, India) Lives and works in Esopus, New York EDUCATION 1971 The New York Studio School, New York, NY 1970 Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Skowhegan, ME 1969 The Byam Shaw School of Painting and Drawing, London, UK SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 High Anxiety, Nicelle Beauchene Gallery, New York, NY 2018 Doors, Freddy Gallery, Harris, NY Crazy Cats, Elizabeth Harris Gallery, New York, NY 2015 The Antipodes, William Mora Galleries, Melbourne, Australia Raw Cuts, Cross Contemporary Art, Saugerties, NY 2014 Death and The Sea, Owen James Gallery, Brooklyn, NY Paintings of Modern Life, Carroll and Sons, Boston, MA Some Stories, Elizabeth Harris Gallery, New York, NY 2012 Art History: Fact and Fiction, Carroll and Sons, Boston, MA 2011 Art History: Fact and Fiction, Byrdcliffe Guild, Woodstock, NY 2007 Rough Terrain, Elizabeth Harris Gallery, New York, NY 2005 New Paintings, Bernard Toale Gallery, Boston, MA 2004 Richard Bosman, Elizabeth Harris Gallery, New York, NY Richard Bosman, Mark Moore Gallery, Santa Monica, CA 2003 Richard Bosman, Elizabeth Harris Gallery, New York, NY Just Below the Surface: Current and Early Relief Prints, Solo Impression Inc, New York, NY 1996 Prints by Richard Bosman From the Collection of Wilson Nolen, The Century Association, New York, NY Close to the Surface - The Expressionist Prints of Eduard Munch and Richard Bosman, The Columbus Museum, Columbus, GA 1995 Prints by Richard Bosman, Quartet Editions, Chicago, IL 1994 Richard Bosman: Fragments, -

Donald Lipski/Oral History

Donald Lipski/Oral History Southeastern Center for Contemporary Art January 22—April 17, 1994 Galerie Leiong May—June, 1994 In earlier times, whole communi- Donald Lipski's "Oral History" is the first exhibition in SECCA's pilot project, ties worked to produce the crop, Artist and the Community Conceived as an ongoing series, Artist and the and the farmer's entire family Community is a residency program that will result in the creation of new works actively participated in growing, to be exhibited at SECCA and elsewhere in the community. Participating curing, and preparing the tobacco artists will focus on specific aspects of life in Winston-Salem, from industry to for market. The intense commit- education and social welfare. ment demanded by the crop strengthened the bonds of family By structuring an interactive relationship with the resident artists. Artist and the and community Community aims to involve community members in the creative process, thus expanding SECCA's outreach in the community, and strengthening SECCA's ties with other local cultural, educational, and civic organizations. Upcoming projects for 1994 are Tim Rollins and K.O.S., who will work with the public school system to create a mural based on Stephen Crane's The Red Badge of Courage; and Fred Wilson, who will work with Winston-Salem's historical orga- nizations to interpret and trace the history of Winston-Salem's African- Americans, including his own ancestors. In 1995 Hope Sandrow and Willie Birch will be residents, working, respectively, with local college women and public school children. Donald Lipski began the first segment of Artist and the Community with a three-week residency in spring 1993. -

Hank Willis Thomas

Goodman Gallery Hank Willis Thomas Biography Hank Willis Thomas (b. 1976, New Jersey, United States) is a conceptual artist working primarily with themes related to perspective, identity, commodity, media, and popular culture. Thomas has exhibited throughout the United States and abroad including the International Center of Photography, New York; Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, Spain; Musée du quai Branly, Paris; Hong Kong Arts Centre, Hong Kong, and the Witte de With Center for Contemporary Art, Netherlands. Thomas’ work is included in numerous public collections including the Museum of Modern Art, New York; Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; Whitney Museum of American Art, New York; Brooklyn Museum, New York; High Museum of Art, Atlanta, and National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C. His collaborative projects include Question Bridge: Black Males, In Search Of The Truth (The Truth Booth), Writing on the Wall, and the artist-run initiative for art and civic engagement For Freedoms, which in 2017 was awarded the ICP Infinity Award for New Media and Online Platform. Thomas is also the recipient of the Gordon Parks Foundation Fellowship (2019), the Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship (2018), Art for Justice Grant (2018), AIMIA | AGO Photography Prize (2017), Soros Equality Fellowship (2017), and is a member of the New York City Public Design Commission. Thomas holds a B.F.A. from New York University (1998) and an M.A./M.F.A. from the California College of the Arts (2004). In 2017, he received honorary doctorates from the Maryland Institute of Art and the Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts. Artist Statement Hank Willis Thomas is an American visual photographer whose primary interested are in race, advertising and popular culture. -

African Collection

calendar African Art from the Permanent Collection Collections of the RMCA: January 1, 2005–December 31, 2008 Headdresses Neuberger Museum of Art, SUNY Purchase December 20, 2006–September 30, 2007 Purchase, NY Royal Museum for Central Africa Tervuren, Belgium African Vision: Highlights from the The Walt Disney-Tishman African Art Collection Continuity and Change: February 15, 2007–September 7, 2008 Three Generations of Ethiopian Artists AFRICAN National Museum of African Art May 25–December 8, 2007 Washington, DC Diggs Gallery, Winston-Salem State University Winston-Salem, NC COLLECTION Afrique Noire: Fotografien von Didier Ruef Eternal Ancestors: Made possible by SunTrust Bank April 25– August 19, 2007 The Art of the Central African Reliquary Völkerkunemuseum der Universität Zürich October 2, 2007–March 2, 2008 Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/afar/article-pdf/40/3/95/1816128/afar.2007.40.3.95.pdf by guest on 26 September 2021 Zürich, Switzerland Metropolitan Museum of Art New York, NY Anxious Objects: Willie Cole’s Favorite Brands Inscribing Meaning: June 15–September 2, 2007 Writing and Graphic Systems in African Art Frye Art Museum May 9–September 3, 2007 Seattle, WA National Museum of African Art Washington, DC September 26, 2007–January 7, 2008 Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University October 14, 2007–February 17, 2008 Stanford, CA Fowler Museum at UCLA Los Angeles, CA Art of Being Tuareg: Saharan Nomads in a Modern World Meditations on African Art: May 9–August 19, 2007 Color Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University April 18–August 19, 2007 Stanford, CA Baltimore Museum of Art Baltimore, MD Bamako: African Photographers Meditations on African Art: May 18–September 25, 2007 Pattern Museum of the African Diaspora August 29, 2007–January 13, 2008 San Francisco, CA Baltimore Museum of Art Baltimore, MD Benin—Könige und Rituale. -

As We Enter the 2005-06 Academic Year, It Is Clear That Rutgers-Newark

ANNUAL ACCOUNTABILITY REPORT 2005-2006 FACULTY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES RUTGERS THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW JERSEY TABLE OF CONTENTS A Message from the Dean...............................................................................................................i Students ..........................................................................................................................................1 Size of the Student Body.....................................................................................................1 Retention Rates...................................................................................................................1 Registrations........................................................................................................................1 Characteristics.....................................................................................................................1 Number of Students Taught/Credit Hours ...........................................................................3 Admissions ..........................................................................................................................4 Academic Foundations Center/Educational Opportunity Fund .........................................15 Office of the Dean of Student Affairs.................................................................................21 Faculty ..........................................................................................................................................33 -

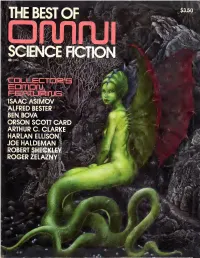

Best of OMNI Issue #1

i * HI 111 1 seiHCEraafioN EDITOQA ^ FEl^TJJliirUE: ISAAC asjjmov ALFRED BESTER BEN BOVA ORSON SCOTT CARD ARTHUR C. CLARKE ( HARLAN ELLISONf JOE HALDEMAN 1 ROBERT SHE©KU^ ROGER ZELAZNY& THE BEST OF onnrui SCIENCE FCTION EDITED BY BEN BOVA AND DON MYRUS DO OMNI SOCIETY THE BEST OF onnrui SCIENCE FICTION FOL.NDI few by Iscac Asir-ic-.: i i,s"al;cn by H R, Giger IAT TELLS THE TIME fit y HclanFI ison. lustro~-cn by 'vlaf. -(lorwein - : c ci cl! Lee-;, fex" ba Kara een vein Cera. Ls-'OicnoyEveyri byb' by Scot Morns siralionoy ivelya oyer okoloy tsx' by F C. Duront III I m NO FUTURE IN IT fiction by Joe Haldeirar . aire ;.- by C ofrti ed -e -weir, - GALATEA GALANTE fiction c-v '''ea Bey ei ; lustration by H. R. Giger ALIEN LANDSCAPES pictorial by Les Edwards, John Harris, Terry Ookes, and Tony Roberts y^\ KINS VAN fict on by Ben Rove, i ustronor by John Schoenherr SPACE CITIES pictorial by Harry Harrison Cover pointing by Pierre Lacombe HALFJACKficorioy ~'cy? '.<? -:-. .:.-'- v -:.- bv Ivtchsl Henricot SANDKINGS fiction by George R. R Martin llustrafol by Ernst Fuchs PLANET STORV pictor c ey - rr 3'ir^s a:-'d -crry Harrison : ARTHUR C.C .ARk'E!,-i:ef,igvv a-d i ...s-ofc', ::v VcIcoItsS. Kirk Copyriari jM9.'5. '97y. !930 by Or.n. P..Ld--:lioni- -te-e.:!cnal -id All nglrs 'ess : aiaies o ArTon,.;. Ni :!.-: c""""b so;* tray ::,; epr-duosd n; -'onsTii-tec n any torn- o- 'lecfifl-ica i--:udinc bhr-.iDr.c-pvi-g (eco'OV'g. -

1 Proposal Information Summary: the Ph.D

Graduate Center of the City University of New York | Principal Investigator: Claire Bishop | Grant Reference NumBer: 1811-06406 Proposal Information Summary: The Ph.D. Program in Art History at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York (CUNY) proposes a renewal of funding by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for the project “New Initiatives in Curatorial Training.” We are requesting $650,000 for a five-year renewal that would deepen and formaliZe the program’s long-standing commitment to training future curators and other museum and arts professionals. The project will build on a successful three-year pilot, as well as a four-year renewal grant, that enabled the Ph.D. Program in Art History to strengthen curatorial training in art history, with a particular focus on Modern and Contemporary topics. As a result of the grants, the Ph.D. Program has forged closer links with exhibiting institutions in the city and nearby region through teaching and fellowships; these institutions include El Museo del Barrio, the Hispanic Society, the Newark Museum, MoMA, Dia Center for the Arts, the Morgan Library, the Queens Museum, the Whitney Museum, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. It has also enriched the relationship between the Ph.D. Program in Art History and the Graduate Center’s own James Gallery, leading to a series of student-curated exhibitions there. A final Mellon Foundation grant for this initiative is sought to continue addressing the intersection of research and curatorial training, but with two new emphases: (1) to enhance the diversity of curatorial training at the Graduate Center by broadening the curriculum and the curatorial opportunities available for the study of global art. -

Organize Your Own: the Politics and Poetics of Self-Determination Movements © 2016 Soberscove Press and Contributing Authors and Artists

1 2 The Politics and Poetics of Self-determination Movements Curated by Daniel Tucker Catalog edited by Anthony Romero Soberscove Press Chicago 2016 Contents Acknowledgements 5 Gathering OURSELVES: A NOTE FROM THE Editor Anthony Romero 7 1 REFLECTIONS OYO: A Conclusion Daniel Tucker 10 Panthers, Patriots, and Poetries in Revolution Mark Nowak 26 Organize Your Own Temporality Rasheedah Phillips 48 Categorical Meditations Mariam Williams 55 On Amber Art Bettina Escauriza 59 Conditions Jen Hofer 64 Bobby Lee’s Hands Fred Moten 69 2 PANELS Organize Your Own? Asian Arts Initiative, Philadelphia 74 Organize Your Own? The Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago 93 Original Rainbow Coalition Slought Foundation, Philadelphia 107 Original Rainbow Coalition Columbia College, Chicago 129 Artists Talk The Leviton Gallery at Columbia College, Chicago 152 3 PROJECTS and CONTRIBUTIONS Amber Art and Design 170 Anne Braden Institute for Social Justice Research 172 Dan S. Wang 174 Dave Pabellon 178 Frank Sherlock 182 Irina Contreras 185 Keep Strong Magazine 188 Marissa Johnson-Valenzuela 192 Mary Patten 200 Matt Neff 204 Rashayla Marie Brown 206 Red76, Society Editions, and Hy Thurman 208 Robby Herbst 210 Rosten Woo 214 Salem Collo-Julin 218 The R. F. Kampfer Revolutionary Literature Archive 223 Thomas Graves and Jennifer Kidwell 225 Thread Makes Blanket 228 Works Progress with Jayanthi Kyle 230 4 CONTRIBUTORS, STAFF, ADVISORS 234 Acknowledgements Major support for Organize Your Own has been provided by The Pew Center for Arts & Heritage, with additional support from collaborating venues, including: the Averill and Bernard Leviton Gallery at Columbia College Chicago, Kelly Writers House’s Brodsky Gallery at the University of Pennsylvania, the Slought Foundation, the Asian Arts Initiative, the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, and others.