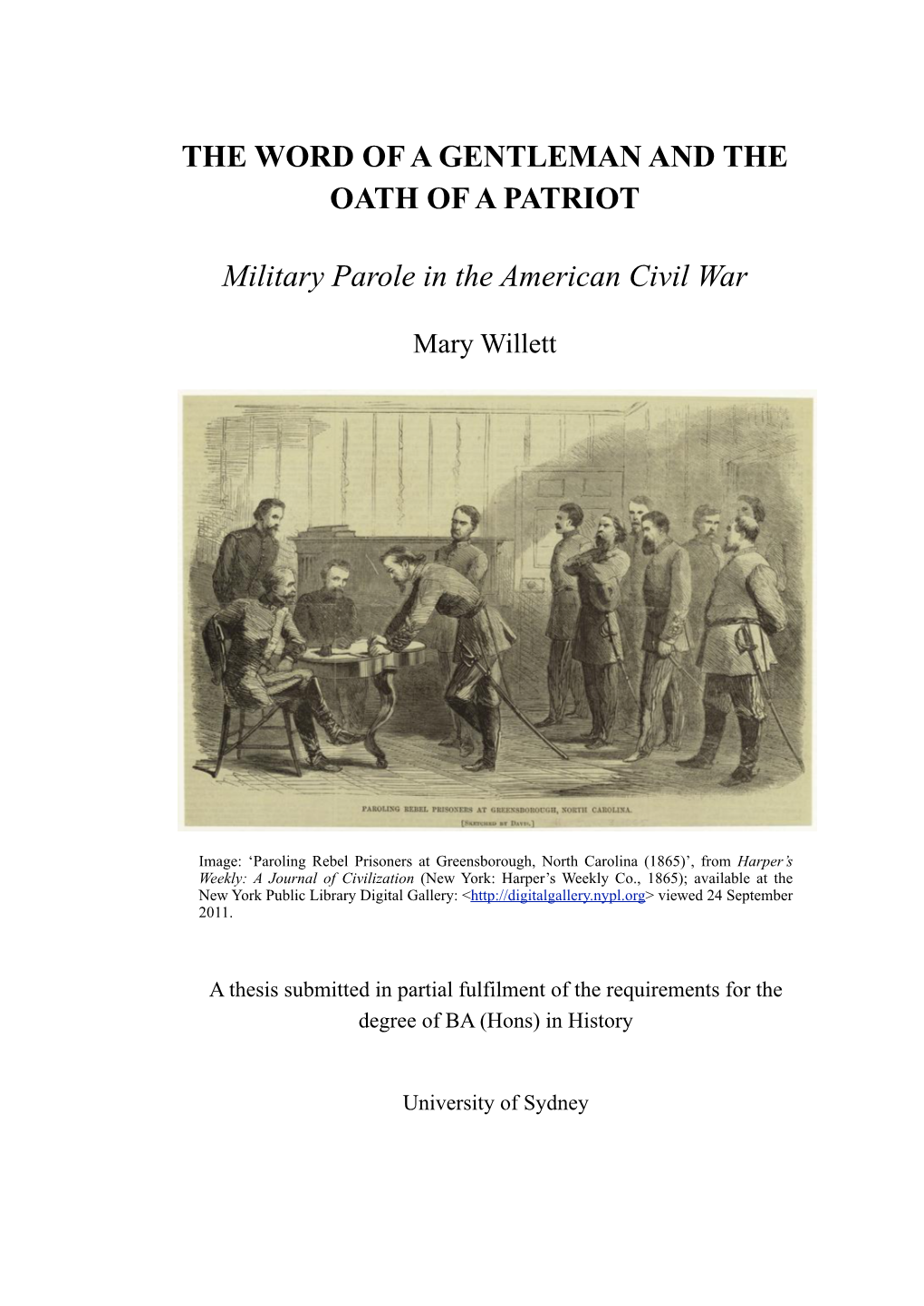

Complete Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Importance of Civil Military Relations in Complex Conflicts: Success And

THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL The Importance of Civil Military Relations in Complex Conflicts: Success and Failure in the Border States, Civil War Kentucky and Missouri, 1860-62. Being a Thesis submitted for the Degree of PhD, Department of Politics and International Studies In the University of Hull By Carl William Piper, BA (Lancs),MA June, 2011 Contents Introduction, p.1 Literary Review, p.60 The Border States in the Secession Crisis, p115 Case Study 1: Missouri April to September, 1861, p.160 Case Study 2: Kentucky April to September, 1861, p.212 Case Study 3: Forts Henry and Donelson, p.263 Case Study 4: The Perryville Campaign June to November, 1862, p.319 Conclusion, p.377 Bibliography, p.418 Introduction Despite taking place in the mid-nineteenth century the U.S. Civil War still offers numerous crucial insights into modern armed conflicts. A current or future federation or new ‘nation’ may face fundamental political differences, even irreconcilable difficulties, which can only be settled by force. In future states will inevitably face both separatist issues and polarised argument over the political development of their nation. It is probable that a civil war may again occur where the world may watch and consider forms of intervention, including military force, but be unwilling to do so decisively. This type of Civil War therefore remains historically significant, offering lessons for approaching the problems of strategy in a politically complex environment. Equally it offers insights into civil-military relations in highly complex conflicts where loyalties are not always clear. Success and ultimate triumph in the U.S. -

Bowling Green Civil War Round Table Newsletter History

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Bowling Green Civil War Round Table Newsletter History 9-2016 Bowling Green Civil War Round Table Newsletter (Sept. 2016) Manuscripts & Folklife Archives Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/civil_war Part of the Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Folklife Archives, Manuscripts &, "Bowling Green Civil War Round Table Newsletter (Sept. 2016)" (2016). Bowling Green Civil War Round Table Newsletter. Paper 10. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/civil_war/10 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bowling Green Civil War Round Table Newsletter by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Founded March 2011 – Bowling Green, Kentucky President –Tom Carr; Vice President - Jonathan Jeffrey; Secretary – Carol Crowe-Carraco; Treasurer – Robert Dietle; Advisors – Glenn LaFantasie and - Greg Biggs (Program Chair and President-Clarksville CWRT) The Bowling Green, KY Civil War Round Table meets on the 3rd Tuesday of each month (except June, July, and December). Email: [email protected] We meet at 7:00 p.m. on Tuesday, September 20th in Cherry Hall 125 on the Campus of Western Kentucky University. Our meetings are always open to the public. Members please bring a friend or two – new recruits are always welcome. Our Program for September 20th 2016: The Battle of Spotsylvania Court House Spotsylvania Court House – perhaps the most forgotten major battle of the Civil War. Over 150,000 soldiers struggled for 13-days along a six-mile front in central Virginia in May 1864, leaving over 30,000 casualties on the battleground of Spotsylvania Court House. -

June 2020 Margaret Stewart & the Birth of the Red Douglases, 1389

VOL 47 ISSUE 2 June 2020 IN THIS ISSUE PAGE WHAT TO SEE 2 OFFICERS & REGENTS 4 President’s Comments 5 SPECIAL ANNOUNCEMENTS 6 Stand-off at Tantallon Castle: Margaret Stewart & the Birth of the Red Douglases, 1389 by Dr. Callum Watson 13 Tantallon Castle by Ian Douglas 17 Scotland and the Confederate States of America by Colin MacDonald 21 CDSNA Septs & Allied Families: Harkness, Inglis, Kilgore 24 NEWS from ALL OVER 31 2021 CDSNA GMM INFORMATION UPDATE BACK COVER – List of the Sept & Allied Family Names Recognized by CDSNA J u n e 2 0 2 0 Dubh Ghlase P a g e | 2 NEWSLETTER FOUNDER Gilbert F. Douglas, JR. MD (deceased) OFFICERS REGENTS President UNITED STATES INDIANA OKLAHOMA Jim & Sandy Douglas Jody Blaylock Chuck Mirabile ALABAMA - Gilbert F. Douglas III 765-296-2710 405-985-9704 7403 S. Parfet Ct. 205-222-7664 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Littleton, CO 80127-6109 IOWA – Regent wanted for the OREGON (North) Phone: 720-934-6901 ALASKA --- Regent wanted Quad City area Carol Bianchini [email protected] 971-300-8593 ARIZONA KANSAS --- Regent wanted for Wichita [email protected] Barbara J. Wise area Vice-President 520-991-9539 OREGON (South) – Regent wanted [email protected] KENTUCKY --- Co-Regents wanted Tim Tyler Elizabeth Martin PENNSYLVANIA -- Regent and/or 7892 Northlake Dr #107 ARKANSAS – Co-Regent Wanted 931-289-6517 Co-Regents wanted Diana Kay Stell [email protected] Huntington Beach, CA 92647 501-757-2881 SOUTH CAROLINA Co-Regent Phones: 1-800-454-5264 [email protected] LOUISIANA – Regent/Co-Regent wanted George W. -

Military History of Kentucky

THE AMERICAN GUIDE SERIES Military History of Kentucky CHRONOLOGICALLY ARRANGED Written by Workers of the Federal Writers Project of the Works Progress Administration for the State of Kentucky Sponsored by THE MILITARY DEPARTMENT OF KENTUCKY G. LEE McCLAIN, The Adjutant General Anna Virumque Cano - Virgil (I sing of arms and men) ILLUSTRATED Military History of Kentucky FIRST PUBLISHED IN JULY, 1939 WORKS PROGRESS ADMINISTRATION F. C. Harrington, Administrator Florence S. Kerr, Assistant Administrator Henry G. Alsberg, Director of The Federal Writers Project COPYRIGHT 1939 BY THE ADJUTANT GENERAL OF KENTUCKY PRINTED BY THE STATE JOURNAL FRANKFORT, KY. All rights are reserved, including the rights to reproduce this book a parts thereof in any form. ii Military History of Kentucky BRIG. GEN. G. LEE McCLAIN, KY. N. G. The Adjutant General iii Military History of Kentucky MAJOR JOSEPH M. KELLY, KY. N. G. Assistant Adjutant General, U.S. P. and D. O. iv Military History of Kentucky Foreword Frankfort, Kentucky, January 1, 1939. HIS EXCELLENCY, ALBERT BENJAMIN CHANDLER, Governor of Kentucky and Commander-in-Chief, Kentucky National Guard, Frankfort, Kentucky. SIR: I have the pleasure of submitting a report of the National Guard of Kentucky showing its origin, development and progress, chronologically arranged. This report is in the form of a history of the military units of Kentucky. The purpose of this Military History of Kentucky is to present a written record which always will be available to the people of Kentucky relating something of the accomplishments of Kentucky soldiers. It will be observed that from the time the first settlers came to our state, down to the present day, Kentucky soldiers have been ever ready to protect the lives, homes, and property of the citizens of the state with vigor and courage. -

History and Battle Flag of the 32Nd & 45Th Mississippi Infantry Regiment

“LOST NATIONAL TREASURE” DISCOVERED! Compiled by Robert E. Swinson & Edited by Greg Biggs Hardee/Cleburne 1864 (Type 1) Battle Flag Issued to the 32nd & 45th Mississippi Volunteer Infantry Regiment (Field Consolidated) HARDEE / CLEBURNE 1864 (Type 1) Pattern Flag Confederate Regimental Battle Flag Issued February 1864 to: 32 nd & 45 th Mississippi Volunteer Infantry Regiment (Consolidated); 45 th Mississippi Also Known As 33 rd (Hardcastle’s) And Third Battalion Mississippi Infantry Copyrighted: 2002-2006 – Robert E. Swinson HARDEE / CLEBURNE 1864 (Type 1) Battle Flag Table of Contents “Lost National Treasure” Discovered 3 Introduction 4 Lowrey’s Brigade and the Third Mississippi Infantry Battalion; 32nd Mississippi, 33rd Mississippi (Hardcastle’s) and 45th Mississippi Infantry Regiments 4 Hardee Pattern Battle Flags; and the 32 nd & 45 th Mississippi Flag 22 The “Colorful” Flag Bearer of the Third Battalion Mississippi Infantry 27 Virtual CSA Purple Heart Award 33 What Lowrey’s Brigade Faced at the Battle of Franklin From Soldiers’ Views 33 Carnton Plantation and McGavock Confederate Cemetery 38 Fountain B. Carter House and Battle of Franklin 40 Finding This Flag and Discovering Its Heritage 41 Flag Authentication 43 Unpublished Sources - Documents and Items of Support 44 Published Sources (Partial List) - Documents and Items of Support 46 Additional Identified Sources (Mostly Unpublished) 46 Contact Information 47 Work in progress 47 Civil War Flag, Regiment and Name Research Services Available 47 May 8, 2006 2 HARDEE / CLEBURNE 1864 (Type 1) Battle Flag HARDEE / CLEBURNE 1864 (Type 1) Pattern Flag Confederate Regimental Battle Flag Issued February 1864 to: 32 nd & 45 th Mississippi Volunteer Infantry Regiment (Consolidated); th rd 45 Mississippi Also Known As 33 (Hardcastle’s) And Third Battalion Mississippi Infantry Hardee/Cleburne 1864 (Type 1) Battle Flag Issued to the 32nd & 45th Mississippi Volunteer Infantry Regiment (Field Consolidated) (Copyrighted: 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005 and 2006 – Robert E. -

The Kentucky Campaign, the Battle of Antietam, the War in Virginia and the West, 1862-1863

THE KENTUCKY CAMPAIGN, THE BATTLE OF ANTIETAM, THE WAR IN VIRGINIA AND THE WEST, 1862-1863 Created by Morgan Fleming 1st period IB HL History of the Americas What is the Kentucky Campaign? • Was a series of maneuvers and battles in East Tennessee and Kentucky in 1862 during the American Civil War. • Also know as Confederate Heartland Offensive. • Kentucky Campaign was confederacy trying to take Kentucky from confederacy from being a border state • Issued on September 22, 1862. • South wanted Kentucky: North wanted to make sure they didn’t get it so they followed the South prepared for battle States during the Kentucky Campaign (Orange with green lines are border states) Battle in the Kentucky Campaign in Main Western Theater • There were series of battles: • Perryville (Battle of Chaplin Hills) • Battle of Corinth • Camp Wildcat • Munfordville • Mill Springs • Middle Creek • Richmond • Chattanooga I • Murfreesboro I Battles in The Kentucky Campaign • Munfordville - September 14-17, 1862. Result: Confederate victory • Perryville - October 8, 1862. Result: Union strategic victory • Battle of Corinth - October 3-4, 1862. Result: Union Victory • Camp Wildcat - October 21, 1861. Result: Union victory • Middle Creek - January 10, 1862. Result: Union victory (indecisive) • Mill Springs - January 19, 1862. Result: Union victory Battle of Perryville • Also known as the Battle of Chaplin Hills • October 8, 1862 • Perryville, Boyle County Kentucky • Outcome was inconclusive • Union: Don Carlos Buell vs. Confederate: Braxton Bragg • Largest Battle fought in the state of Kentucky Munfordville • Also known as Battle of Green River Bridge • September 14 - 17, 1862 • Confederate : Colonel Wilder vs. Union : General Buell • Estimated Casualties: 4,862 total (Union 4,148; Confederate 714) Virginia Battles1862-1863 -1862 • May: General McClellan's troops invaded Yorktown and awaited more troops in Williamsburg in Hampton Roads. -

The Paper Trail of the Civil War in Kentucky 1861-1865 1

The Paper Trail of the Civil War in Kentucky 1861-1865 1 The This publication pertaining to Paper the Civil War in Kentucky is a special edition spanning the Trail four years of the Civil War 1861-1865. Almost every entry Of the in this publication is refer- enced to the specific item it was Civil War obtained from. In Kentucky It will be incorporated into the “work in progress” book enti- 1861-1865 tled, “The Paper Trail of the Ken- tucky National Guard” that will be published in 2002. The finished book will be a compilation of the military his- tory of each of the 120 counties Compiled by Colonel (Ret.) Ar- of the Commonwealth. mando “Al” Alfaro The over 720 pages will be an excellent reference book on Kentucky’s military history from the War of 1812 to the Al Alfaro 651 Raven Drive present day Army and Air Frankfort, KY 40601 Kentucky National Guard. 502 223-8318 [email protected] The Paper Trail of the Civil War in Kentucky 1861-1865 2 Index Pg Index Pg Civil War Casualties 3 Henderson 36 22 Courthouses Burned 3 Henry – Hickman 37 Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address 3 Hopkins – Jackson – Jefferson 38 Civil War Unit Organizations 3 Jessamine 41 Civil War Skirmishes 3 Johnson 42 Riders Horse Hoof Determines Death 3 Kenton 43 Kentucky Confederate Units 3 Knott – Knox 44 Kentucky Union Units 4 Larue – Laurel 45 Kentucky US Colored Troop Units 5 Lawrence – Lee – Leslie – Letcher - Lewis 46 Taps 5 Lincoln – Livingston - Madison 47 Civil War Campaign Streamers 6 Logan – Lyon - Madison 48 Seven Civil War Soldiers Become 6 Magoffin 49 Presidents Marion -

Civil War Manuscripts

CIVIL WAR MANUSCRIPTS CIVIL WAR MANUSCRIPTS MANUSCRIPT READING ROW '•'" -"•••-' -'- J+l. MANUSCRIPT READING ROOM CIVIL WAR MANUSCRIPTS A Guide to Collections in the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress Compiled by John R. Sellers LIBRARY OF CONGRESS WASHINGTON 1986 Cover: Ulysses S. Grant Title page: Benjamin F. Butler, Montgomery C. Meigs, Joseph Hooker, and David D. Porter Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Library of Congress. Manuscript Division. Civil War manuscripts. Includes index. Supt. of Docs, no.: LC 42:C49 1. United States—History—Civil War, 1861-1865— Manuscripts—Catalogs. 2. United States—History— Civil War, 1861-1865—Sources—Bibliography—Catalogs. 3. Library of Congress. Manuscript Division—Catalogs. I. Sellers, John R. II. Title. Z1242.L48 1986 [E468] 016.9737 81-607105 ISBN 0-8444-0381-4 The portraits in this guide were reproduced from a photograph album in the James Wadsworth family papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress. The album contains nearly 200 original photographs (numbered sequentially at the top), most of which were autographed by their subjects. The photo- graphs were collected by John Hay, an author and statesman who was Lin- coln's private secretary from 1860 to 1865. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, D.C. 20402. PREFACE To Abraham Lincoln, the Civil War was essentially a people's contest over the maintenance of a government dedi- cated to the elevation of man and the right of every citizen to an unfettered start in the race of life. President Lincoln believed that most Americans understood this, for he liked to boast that while large numbers of Army and Navy officers had resigned their commissions to take up arms against the government, not one common soldier or sailor was known to have deserted his post to fight for the Confederacy. -

The Kentucky Campaign and the Battle of Antietam-2

Melanie Cartron IB History of the Americas Period 1 The Civil War 1862 By 1862, the success of the Confederate army was declining. The Union was thriving after victories at Fort Donelson and Fort Henry and had gained control of several key points of power, including New Orleans and much of West Tennessee. The Confederacy was looking for a way to improve their standings in the war, especially in the Western Theatre. General Braxton Bragg Born on March 22, 1817 in Warrenton, North Carolina Graduated from West Point in 1837 where frontal assaults were the most popular war tactic Served in the Seminole and Mexican Wars Characterized as temperamental and rash Relationship With Jefferson Davis During the Mexican War, Braxton Bragg helped the regiment of Jefferson Davis to hold off an army of Mexicans. Both men admired and respected each other greatly, which would lead Davis to favor and prioritize Bragg in several key and critical decisions. The Confederate Heartland Offensive In June 1862, Jefferson Davis appointed Braxton Bragg as General of the Army of Mississippi, hoping he would gain the much needed success for the Confederacy. Bragg plotted to invade Kentucky, hoping to gain support and troops as well as shift the focus of the war. Main goal was to make Kentucky part of the Confederacy Kentucky as a Border State At the beginning of the war, Kentucky remained neutral Was a slavery state, but did not secede While the Kentucky government would eventually become Unionist, Kentucky’s potential to becoming supportive of the Confederacy sparked interest Bragg’s Invasion of Kentucky In August of 1862, Bragg began his invasion of Kentucky He left Mississippi with 34,000 men and hoped to join forces with Lieutenant General Edmund Kirby Smith's 18,000 soldiers once in Kentucky. -

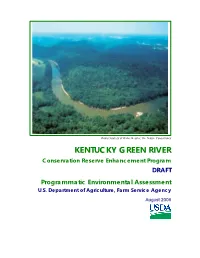

KENTUCKY GREEN RIVER Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program DRAFT Programmatic Environmental Assessment U.S

Photo Courtesy of Richie Kessler, The Nature Conservancy KENTUCKY GREEN RIVER Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program DRAFT Programmatic Environmental Assessment U.S. Department of Agriculture, Farm Service Agency August 2006 Abstract Mandated Action: The U.S. Department of Agriculture, Commodity Credit Corporation (USDA/CCC) and the Commonwealth of Kentucky have agreed to implement the Kentucky Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program (CREP), a component of the national Conservation Reserve Program (CRP). CREP is a voluntary program for agricultural landowners. USDA is authorized by the provisions of the Food Security Act of 1985, as amended (1985 Act) (16 U.S.C. 3830 et seq.), and its regulations at 7 CFR Part 1410. In accordance with the 1985 Act, USDA/CCC is seeking authorization to enroll lands into CREP through December 31, 2007. Type of Document: Programmatic Environmental Assessment Lead Federal Agency: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Farm Service Agency For Further Information: Matthew Ponish Conservation and Environmental Programs Division U.S. Department of Agriculture, Farm Service Agency 1400 Independence Ave. S.W. Washington, DC 20250 202-720-6853 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.fsa.usda.gov/dafp/cepd/crep.htm ************************************************************************ The Kentucky Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program Programmatic Environmental Assessment has been prepared pursuant to the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969, as amended (42 U.S.C. 4321-4347); the Council on Environmental Quality regulations (40 CFR Parts 1500-1508); USDA-Farm Service Agency draft environmental regulations (7 CFR Part 799.4, Subpart G); and USDA-Farm Service Agency 1-EQ, Revision 1, Environmental Quality Programs, dated November 19, 2004. -

National Register of Historic Places 2001 Weekly Lists

National Register of Historic Places 2001 Weekly Lists WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 12/26/00 THROUGH 12/29/00 .................................... 3 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 1/02/01 THROUGH 1/05/01 ........................................ 7 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 1/08/01 THROUGH 1/12/01 ...................................... 12 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 1/16/01 THROUGH 1/19/01 ...................................... 15 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 1/22/01 THROUGH 1/26/01 ...................................... 19 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 1/29/01 THROUGH 2/02/01 ...................................... 24 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 2/05/01 THROUGH 2/09/01 ...................................... 27 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 2/12/01 THROUGH 2/16/01 ...................................... 31 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 2/19/01 THROUGH 2/23/01 ...................................... 34 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 2/26/01 THROUGH 3/02/01 ...................................... 36 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 3/05/01 THROUGH 3/09/01 ...................................... 40 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 3/12/01 THROUGH 3/16/01 ...................................... 43 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 3/19/01 THROUGH 3/23/01 ...................................... 47 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 3/26/01 THROUGH 3/30/01 ...................................... 49 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 4/02/01 THROUGH 4/06/01 ...................................... 53 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 4/09/01 THROUGH 4/13/01 ...................................... 55 WEEKLY LIST OF ACTIONS TAKEN ON PROPERTIES: 4/16/01 THROUGH 4/20/01 ..................................... -

November 2012 from the Adjutant

November 2012 1 I Salute The Confederate Flag; With Affection, Reverence, And Undying Devotion To The Cause For Which It Stands. From The Adjutant The General Robert E. Rodes Camp 262, Sons of Confederate Veterans, will meet on Thursday night, November 8, 2012. The meeting starts at 7 PM in the Tuscaloosa Public Library Rotary Room, 2nd Floor. The Library is located at 1801 Jack Warner Parkway. Annual dues were due August 1, 2012, and are delinquent after August 31st, 2012. Annual dues are $60.00 ($30.00 National, $10.00 Alabama Division and $20.00 our camp); $67.50 if delinquent. Please make your checks payable to: Gen. R.E. Rodes Camp 262, SCV, and mail them to: Gen. R.E. Rodes Camp 262, SCV, PO Box 1417, Tuscaloosa, AL 35403. I am pleased to announce a new topic will be covered each month in the Alabama Section of the newsletter entitled “Alabama Civil War Shipwrecks”, covering both Confederate and Union shipwrecks in Alabama waters. The Index of Articles and the listing of Camp Officers are now on Page Two. Look for “Sons of Confederate Veterans Camp #262 Tuscaloosa, AL” on Facebook, and “Like” us. The Sons of Confederate Veterans is the direct heir of the United Confederate Veterans, and is the oldest hereditary organization for male descendants of Confederate soldiers. Organized at Richmond, Virginia in 1896; the SCV continues to serve as a historical, patriotic, and non-political organization dedicated to ensuring that a true history of the 1861-1865 period is preserved. Membership is open to all male descendants of any veteran who served honorably in the Confederate military.