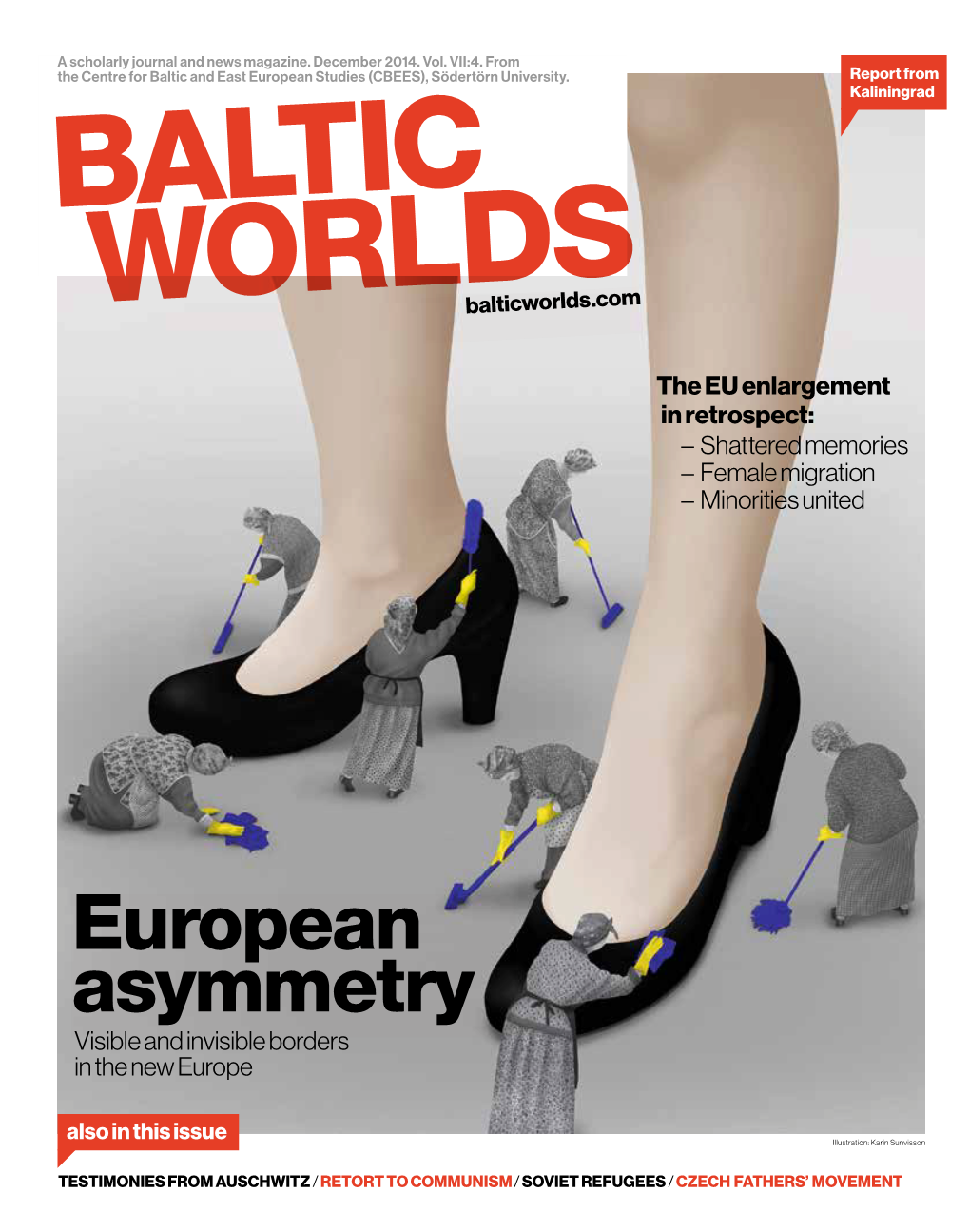

Please Download Issue 4 2014 Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Holocaust Memorial Days an Overview of Remembrance and Education in the OSCE Region

Holocaust Memorial Days An overview of remembrance and education in the OSCE region 27 January 2015 Updated October 2015 Table of Contents Foreword .................................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 2 Albania ................................................................................................................................. 13 Andorra ................................................................................................................................. 14 Armenia ................................................................................................................................ 16 Austria .................................................................................................................................. 17 Azerbaijan ............................................................................................................................ 19 Belarus .................................................................................................................................. 21 Belgium ................................................................................................................................ 23 Bosnia and Herzegovina ....................................................................................................... 25 Bulgaria ............................................................................................................................... -

A Turbulent Year for Ukraine Urbulent Was the Way to Describe 2009 for Ukraine, Which Plunged Into Financial Crisis

No. 3 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, JANUARY 17, 2010 5 2009: THE YEAR IN REVIEW A turbulent year for Ukraine urbulent was the way to describe 2009 for Ukraine, which plunged into financial crisis. No other European country suffered as much as TUkraine, whose currency was devalued by more than 60 percent since its peak of 4.95 hrv per $1 in August 2008. In addition, the country’s industrial production fell by 31 percent in 2009. Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko con- fronted the challenge of minimizing the crisis fallout, while at the same time campaigning for the 2010 presi- dential elections. Her critics attacked her for pursuing populist policies, such as increasing wages and hiring more government staff, when the state treasury was broke as early as the spring. Ms. Tymoshenko herself admitted that her gov- ernment would not have been able to make all its pay- ments without the help of three tranches of loans, worth approximately $10.6 billion, provided by the International Monetary Fund. Her critics believe that instead of borrowing money, Ms. Tymoshenko should have been introducing radical reforms to the Ukrainian economy, reducing government waste, eliminating out- dated Soviet-era benefits and trimming the bureaucracy. The year began with what is becoming an annual tra- Offi cial Website of Ukraine’s President dition in Ukraine – a natural gas conflict provoked by the government of Russian Federation Prime Minister President Viktor Yushchenko and Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko at the heated February 10 meeting of Vladimir Putin. Whereas the New Year’s Day crisis of the National Security and Defense Council. -

HADIFOGSÁG, MÁLENKIJ ROBOT, GULÁG Kárpát-Medencei Magyarok És Németek Elhurcolása a Szovjetunió Hadifogoly- És Kényszermunkatáboraiba (1944–1953)

HADIFOGSÁG, MÁLENKIJ ROBOT, GULÁG Kárpát-medencei magyarok és németek elhurcolása a Szovjetunió hadifogoly- és kényszermunkatáboraiba (1944–1953) Nemzetközi tudományos konferencia Beregszász, 2016. november 17–20. A II. Rákóczi Ferenc Kárpátaljai Magyar Főiskola Lehoczky Tivadar Társadalomtudományi Kutatóközpontjának kiadványa Beregszász–Ungvár 2017 HADIFOGSÁG, MÁLENKIJ ROBOT, GULÁG Kárpát-medencei magyarok és németek elhurcolása a Szovjetunió hadifogoly- és kényszermunkatáboraiba (1944–1953) Nemzetközi tudományos konferencia Beregszász, 2016. november 17–20. A II. Rákóczi Ferenc Kárpátaljai Magyar Főiskola Lehoczky Tivadar Társadalomtudományi Kutatóközpontjának kiadványa Szerkesztette: Molnár D. Erzsébet – Molnár D. István „RIK-U” Kiadó Beregszász–Ungvár 2017 ББК: 63.3 (2POC)-8 УДК: 323.282 (061.3) Т-12 A kötet a 2016. november 17–20-án Beregszászon megtartott a Lehoczky Tivadar Társadalomtudományi Kutatóközpont által rendezett „HADIFOGSÁG, MÁLENKIJ ROBOT, GULÁG. Kárpát-medencei magyarok és németek elhurcolása a Szovjetunió hadifogoly- és kényszermunkatáboraiba (1944–1953)” c. nemzetközi konferencia anyagait tartalmazza. Készült a II. Rákóczi Ferenc Kárpátaljai Magyar Főiskola Lehoczky Tivadar Társadalomtudományi Kutatóközpont műhelyében az Emberi Erőforrások Minisztériuma támogatásával. Szerkesztette: Molnár D. Erzsébet – Molnár D. István A kiadásért felel: Orosz Ildikó Tördelés: Molnár D. István Borító: Molnár D. István Korrektúra: Hnatik-Riskó Márta A közölt tanulmányok tartalmáért a szerzők a felelősek. A kiadvány megjelenését Magyarország -

![Anna Rzeczyńska "Black Ribbon Day", Edward Sołtys, Toronto 2014 : [Recenzja]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5650/anna-rzeczy%C5%84ska-black-ribbon-day-edward-so%C5%82tys-toronto-2014-recenzja-1825650.webp)

Anna Rzeczyńska "Black Ribbon Day", Edward Sołtys, Toronto 2014 : [Recenzja]

Anna Rzeczyńska "Black Ribbon Day", Edward Sołtys, Toronto 2014 : [recenzja] TransCanadiana 8, 326-328 2016 Anna Reczyńska Jagiellonian University in Kraków EDWARD SOŁTYS. BLACK RIBBON DAY. TORONTO: CANADIAN POLISH RESEARCH INSTITUTE, 2014. 313 PAGES. ISBN 978-0-920517-18-5 A black ribbon is a symbol of grief not only in European cultures but also in many others. In the late 1980s, a new movement was born in many different countries, a movement which added a new meaning to the black ribbon. It became a symbol of remembrance of the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact from 1939 and its tragic outcomes for millions of people. Since 1987, Black Ribbon Day has been commemorated around the world on August 23, the anniversary of the signing of the pact. On that day, various forms of protests and demonstrations take place, involving hundreds or thousands of people, featuring speeches by politicians, emigration activists, dissidents, and other people persecuted by totalitarian states. Academic sessions, discussions, and press conferences are also held, focusing on the pact that resulted in World War II, border changes, a new division of Europe, and tragedies of millions of people. The events pinpoint that due to the pact the three Baltic countries, Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia, were forced, for several decades, to be the part of the USSR, while countries at the centre of the continent came under the strong influence of the aforementioned totalitarian regime. Black Ribbon Day also features secular and religious ceremonies commemorating the victims, prisoners, deportees, displaced persons, and refugees, all of whom were victims of totalitarian regimes. -

Viktor Yushchenko

InsIde: • “2009: The Year in Review” – pages 5-35 THEPublished U by theKRA Ukrainian NationalIN AssociationIAN Inc., a fraternal Wnon-profit associationEEKLY Vol. LXXVIII No.3 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, JANUARY 17, 2010 $1/$2 in Ukraine Outgoing New Jersey governor creates Yushchenko’s declining support: Eastern European Heritage Commission Does he really deserve the blame? TRENTON, N.J. – Outgoing New Jersey The 21-member commission will coordi- by Zenon Zawada their staunch support for Ukraine’s inte- Gov. Jon S. Corzine on January 11 signed nate an annual Eastern European Month Kyiv Press Bureau gration into Euro-Atlantic structures. an executive order creating an Eastern Celebration along with other events and Volodymyr Fesenko, board chairman European-American Heritage Commission activities highlighting the rich culture and KYIV – Five years ago, hundreds of of the Penta Center for Applied Research in the Department of State. history of Americans of Eastern European thousands of Ukrainians risked their lives in Kyiv, offered consulting to the “New Jersey is home to over 1 million ancestry. The commission will also work for Viktor Yushchenko to become Presidential Secretariat occasionally dur- Americans of Eastern European ancestry, with the Department of Education to con- Ukraine’s president. Now only about 5 ing Mr. Yushchenko’s term. He’s consid- including Americans of Polish, tinue to develop content and curriculum percent of Ukrainians fully support ered among Ukraine’s most reliable and Hungarian, Ukrainian, Slovak, Czech and guides on Eastern European history for President Yushchenko and would vote for objective political analysts. Mr. Fesenko Lithuanian ancestry. The commission will school children, noted a press released from him in the January 17 election, according studied at Columbia University’s ensure there are opportunities for all of the governor’s office. -

Michael Shafir, “The Nature of Postcommunist Antisemitism in East Central Europe: Ideology’S Backdoor Return” in Journal of Contemporary Antisemitism (JCA), Vol

PROOF ONLY of Michael Shafir, “The Nature of Postcommunist Antisemitism in East Central Europe: Ideology’s Backdoor Return” in Journal of Contemporary Antisemitism (JCA), vol. 1, no. 2, Fall 2018, pp. 33-61. The final version (version of record) is available exclusively from the publishers at: http://journals.academicstudiespress.com/index.php/JCA/article/view/116 JCA 2018 DOI: 10.26613/jca/1.2.12 PROOF: The Nature of Postcommunist Antisemitism in East Central Europe: Ideology’s Backdoor Return Michael Shafir Abstract This article analyzes contemporary antisemitism and Holocaust distortion in Eastern Europe. The main argument is that Brown and Red, Nazism and Communism, respec- tively are not at all equal. In Eastern Europe, in particular, antisemitic ideology is grounded on the rehabilitation of anticommunist national “heroes.” The history of the Holo- caust is thereby distorted. Based on Maurice Halbwachs’s theory of “social frameworks,” the author shows how “competitive martyrdom,” the “Double Genocide” ideology, and “Holocaust obfuscation” are intertwined. Empirically, the paper examines these concepts in Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Hungary, Serbia and Croatia, and Romania. Keywords: Double Genocide, Holocaust Distortion, East European antisemitism, Holocaust, Gulag, anticommunism, national identity INTRODUCTION everywhere subjected the Holocaust to oblivion We are currently facing a huge struggle over or, at best, to manipulation. To use Shari Cohen’s history and collective memory of the twenti- terminology,2 they indulged in “state-organized eth century. Antisemitism plays a crucial role national forgetting.” in this struggle, as we see tendencies to com- New regimes are engaged in what has pare or equate the Holocaust to the history of been termed the search for a “usable past.” As Communism. -

(Pdf) Download

Iznāk kopš 1951. gada decembŗa 2013. DECEMBRIS Nr. 10 (664) Foto: Marks Matsons Latviešu nama 40 gadu jubilejā 19. oktōbrī Lauris Reiniks dziedāja paškomponēto dziesmu „Es skrienu”, viņam piebiedrojās Losandželosas latviešu skolas skolēni un jaunieši SARĪKOJUMU KALENDĀRS 8. decembrī plkst. 11.00 Adventa koncerts baznīcā; no plkst. 10.00 līdz 4.00 Ziemsvētku tirdziņš namā 15. decembrī plkst. 12.00 Ziemas saulgriežu svētki latviešu skolā 31. decembrī plkst. 8.00 Jaungada balle Dienvidkalifornijas Latviešu INFORMĀCIJAS BIĻETENS DK LATVIEŠU BIEDRĪBAS VALDE: ir Dienvidkalifornijas latviešu biedrības izdevums Biedrības priekšnieks: Ivars Mičulis Biedrības adrese: 1955 Riverside Dr., Los Angeles, CA 90039 631 N. Pass Ave. Burbank, CA 91505 Raksti Informācijas Biļetenam iesūtāmi redaktorei: Tālr.: 818-842-3639; e-pasts: [email protected] Astrai Moorai Biedrības priekšnieka vietniece: 6157 Carpenter Ave., North Hollywood, CA 91606 Tālr./tālrakstis: 818-980-4748; e-pasts: [email protected] Sandra Gulbe-Puķēna; tālr.: 310-945-6632; Raksti ievietošanai biļetenā iesūtāmi līdz katra e-pasts: [email protected] iepriekšējā mēneša 10. datumam. Iesūtītos rakstus redak- torei ir tiesības īsināt vai rediģēt. Anonimus rakstus Infor- DK LB valdes locekļi: mācijas Biļetenā neievieto. Rakstos izteiktās domas pauž Rūdolfs Hofmanis (biedrzinis), Tamāra Kalniņa (ka- tikai rakstu rakstītāju viedokli, kas var arī nesaskanēt ar siere), Astra Moora (sekretāre), Jānis Daugavietis, izdevēju vai redaktores viedokli. Honorārus IB nemaksā. Valdis Ķeris, Nora Mičule, Valdis Pavlovskis, Pēteris DK LB biedriem par Informācijas Biļetenu nav jāmaksā. Staško, Dace Taube (biedrības pārstāve latviešu Biedru nauda ir $25 gadā, ģimenei – $40 gadā. Par biedru var kļūt, nosūtot biedrības kasierim biedru naudu. Personām, ku- nama valdē), Jānis Taube, Dziesma Tetere, Vilis ŗas nav DK LB biedri, Informācijas Biļetena abonēšanas Zaķis, Aija Zeltiņa-Kalniņa (Losandželosas latviešu maksa ir $35 gadā. -

Canada and the USSR/CIS: Northern Neighbours Partenaires Du Nord : Le Canada Et L'urss/CÉI

Editorial Board / Comité de rédaction Editor-in-Chief Rédacteur en chef Kenneth McRoberts, York University, Canada Associate Editors Rédacteurs adjoints Mary Jean Green, Dartmouth College, U.S.A. Lynette Hunter, University of Leeds, United Kingdom Danielle Juteau, Université de Montréal, Canada Managing Editor Secrétaire de rédaction Guy Leclair, ICCS/CIEC, Ottawa, Canada Advisory Board / Comité consultatif Alessandro Anastasi, Universita di Messina, Italy Michael Burgess, University of Keele, United Kingdom Paul Claval, Université de Paris-Sorbonne (Paris IV), France Dona Davis, University of South Dakota, U.S.A. Peter H. Easingwood, University of Dundee, United Kingdom Ziran He, Guangzhou Institute of Foreign Languages, China Helena G. Komkova, Institute of the USA and Canada, USSR Shirin L. Kudchedkar, SNDT Women’s University, India Karl Lenz, Freie Universität Berlin, Germany Gregory Mahler, University of Mississippi, U.S.A. James P. McCormick, California State University, U.S.A. William Metcalfe, University of Vermont, U.S.A. Chandra Mohan, University of Delhi, India Elaine F. Nardocchio, McMaster University, Canada Satoru Osanai, Chuo University, Japan Manuel Parés I Maicas, Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Espagne Réjean Pelletier, Université Laval, Canada Gemma Persico, Universita di Catania, Italy Richard E. Sherwin, Bar Ilan University, Israel William J. Smyth, St. Patrick’s College, Ireland Sverker Sörlin, Umea University, Sweden Oleg Soroko-Tsupa, Moscow State University, USSR Michèle Therrien, Institut des langues et civilisations orientales, France Gaëtan Tremblay, Université du Québec à Montréal, Canada Hillig J.T. van’t Land, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen, Pays-Bas Mel Watkins, University of Toronto, Canada Gillian Whitlock, Griffith University, Australia Donez Xiques, Brooklyn College, U.S.A. -

Fall 2018 Newsletter

FALL 2018 NEWSLETTER VOC Rallies for Religious Freedom in Asia In July we participated officially in the first-ever “Ministerial to Advance Religious Freedom” hosted by the State Department in Washington, D.C. The gathering—led by Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, Ambassador-at-Large for International Religious Freedom Sam Brownback, and with a keynote by Vice President Mike Pence—convened leaders from across the human rights community and delegations from over 80 nations for three days of productive talks on how to combat persecution and ensure greater respect for religious liberty. In coordination with the Ministerial, VOC hosted a Rally for Religious Freedom in Asia at the U.S. Capitol in observance of Captive Nations Week, a tradition established in 1959 by President Eisenhower to recognize nations VOC held a Rally for Religious Freedom in Asia on Capitol Hill on July 23 in coordination with the State suffering under communist tyranny. Department’s Ministerial to Advance Religious Freedom. Left to Right: Kristina Olney (VOC), Dolkun Isa, Golog Jigme, Paster Nguyen Cong Chinh, Bhuchung Tsering, David Talbot (VOC). Our six speakers were: Rep. Alan in The Hill, Radio Free Asia, and The belief is such an important part of Lowenthal (D-CA) and co-chair of the Washington Examiner. one’s existence that it should not be Congressional Vietnam Caucus; Sen. controlled by the government.” Ted Cruz (R-TX); Pastor Nguyen Cong In his remarks, Pastor Chinh recounted Chinh, former prisoner of conscience how “my family and church have Sen. Ted Cruz spoke -

2018 Annual Report

2018 ANNUAL REPORT On the Cover The Victims of Communism Memorial statue is modeled on the Goddess of Democracy statue erected in Tiananmen Square by peaceful pro-democracy student protestors in 1989. The statue was dedicated by President George W. Bush on June 12, 2007. It was the world’s first memorial dedicated to every victim of communism and stands in sight of the US Capitol, at the corner of New Jersey and Massachusetts Avenues, Northwest. 2 A world free from the false hope of communism. To educate future generations about the ideology, history, and legacy of communism. Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation is an educational and human rights nonprofit organization authorized by a unanimous Act of Congress signed as Public Law 103-199 by President William J. Clinton on December 17, 1993. From 2003 to 2009, President George W. Bush was Honorary Chairman. On June 12, 2007, he dedicated the Victims of Communism Memorial in Washington, DC. 1 A YEAR of ACHIEVEMENTS 2018 IN REVIEW In 2018, a rising generation of Americans warmed to socialism as the territory of the free world shrank. Communist regimes from China to Cuba continued to project power and interfere abroad while persecuting millions of their own people at home, even as former captive nations grappled with the bitter legacy of Soviet occupation. The Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation worked tirelessly in 2018 to teach the truth about the failures of Marxist ideology, to pursue justice for those still striving for freedom under communist regimes, and to honor the memory of the more than 100 million victims of communism. -

Annual Report 2016

2016 Annual Report www.memoryandconscience.eu A Word from the President Dear friends, We have experienced one more busy year of Platform activities. You will read all about in this report. Besides our continuous work with the justice project, the annual conference held in Viljandi Estonia stands out. We discussed the forced displacement of populations and waves of migration in 20th century Europe caused by the policy of totalitarian States. This was a very timely discussion as the world in 2015/16 faced the largest movements of refugees since the Second World War. It is again very clear that an important mission of the Platform is to enlighten people about our common history in order to avoid atrocities and terror from the past to be repeated. Viljandi also included the 2016 Platform prize; this year given to the imprisoned opposition freedom fighter in totalitarian Venezuela, Leopoldo Lopez. The Prize was accepted by Mr Lopez’ father. Another important event worth mentioning was of course the traditional commemoration of 23 August. The Slovak EU Presidency hosted the festivity together with an EU conference. The Platform co-organized the event in Bratislava and presented the winners of a student competition for a proposal of a memorial to the victims of totalitarianism in Brussels. Now we are looking forward to an even busier 2017! Yours sincerely, Göran Lindblad 2016 Annual Report 1 Contents at a Glance A Word from the President ..................................................................................... 1 January ..................................................................................................................... -

Annual Report 2017

2017 Annual Report www.memoryandconscience.eu A Word from the President Dear friends, The year 2017 was for the Platform of European Memory and Conscience a time of both harvesting and sowing. As for the former, we have achieved numerous successes in our Justice 2.0 project, such as the first court decisions in rehabilitation cases, as well as launching the German investigation. As for the latter, we started the competition for the Pan-European Memorial for the Victims of Totalitarianism in Brussels, which was successfully resolved this year. For me, it was a time of returning to active engagement in the Platform‘s work. I still remember the hopes and expectations we held when establishing the PEMC in October 2011. Throughout those years we have fulfilled many of them, but there is still much to be done. I believe we can continue our struggle for truth and justice, but only together. This struggle is bound to become harder without our long-time Managing Director and proven friend, Dr. Neela Winkelmann, whom I would to sincerely thank for her enormous commitment and efforts. Dear Neela, we will all miss you! Along with Neela leaving the Platform, we closed the first and magnificent chapter in PEMC‘s history. Now it‘s up to us to write the next one. Let us continue to sow truth and harvest justice. Yours, Łukasz Kamiński 2017 Annual Report 1 Contents at a Glance A Word from the President ..................................................................................... 1 January .....................................................................................................................