LM Findlay in the French Revolution: a History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heroic Individualism: the Hero As Author in Democratic Culture Alan I

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2006 Heroic individualism: the hero as author in democratic culture Alan I. Baily Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Baily, Alan I., "Heroic individualism: the hero as author in democratic culture" (2006). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1073. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1073 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. HEROIC INDIVIDUALISM: THE HERO AS AUTHOR IN DEMOCRATIC CULTURE A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Political Science by Alan I. Baily B.S., Texas A&M University—Commerce, 1999 M.A., Louisiana State University, 2003 December, 2006 It has been well said that the highest aim in education is analogous to the highest aim in mathematics, namely, to obtain not results but powers , not particular solutions but the means by which endless solutions may be wrought. He is the most effective educator who aims less at perfecting specific acquirements that at producing that mental condition which renders acquirements easy, and leads to their useful application; who does not seek to make his pupils moral by enjoining particular courses of action, but by bringing into activity the feelings and sympathies that must issue in noble action. -

Ralph Waldo Emerson and Thomas Carlyle on Slavery

B093509 1 Examination Number: B093509 Title of work: Ralph Waldo Emerson and Thomas Carlyle on Slavery: Transatlantic Dissentions and Philosophical Connections Programme Name: MSc United States Literature Graduate School of Literatures, Languages & Cultures University of Edinburgh Word count: 15 000 Thomas Carlyle (1854) Ralph Waldo Emerson (1857) Source: archive.org/stream/pastandpresent06carlgoog#page/n10/mode/2up Source: ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/e/emerson/ralph_waldo/portrait.jpg B093509 2 Ralph Waldo Emerson and Thomas Carlyle on Slavery: Transatlantic Dissentions and Philosophical Connections Table of Contents Introduction 3 Chapter One: On Slavery and Labor: Racist Characterizations and 7 Economic Justifications Chapter Two On Democracy and Government: Ruling Elites and 21 Moral Diptychs Chapter Three On War and Abolition: Transoceanic Tensions and 35 Amicable Resolutions Conclusion 49 Bibliography 51 B093509 3 Introduction In his 1841 essay on “Friendship”, Ralph Waldo Emerson defined a “friend” as “a sort of paradox in nature” (348). Perhaps emulating that paradoxical essence, Emerson’s essay was pervaded with constant contradictions: while reiterating his belief in the “absolute insulation of man” (353), Emerson simultaneously depicted “friends” as those who “recognize the deep identity which beneath these disparities unites them” (“Friendship” 350). Relating back to the Platonic myth of recognition, by which one’s soul recognizes what it had previously seen and forgotten, Emerson defined a friend as that “Other” in which one is able to perceive oneself. As Johannes Voelz argued in Transcendental Resistance, “for Emerson, friendship … is a relationship from which we want to extract identity. Friendship is a relationship from which we seek recognition” (137). Indeed, Emerson was mostly concerned with what he called “high friendship” (“Friendship” 350) - an abstract ideality, which inevitably creates “a tension between potentiality and actuality” (Voelz 136). -

NOTICE of PUBLIC HEARING PLEASE TAKE NOTICE That Pursuant to Article 9 of the New

NOTICE OF PUBLIC HEARING PLEASE TAKE NOTICE that pursuant to Article 9 of the New York State Constitution, the provisions of the Town Law and Municipal Home Rule of the State of New York, both as amended, a public hearing will be held in the Town Meeting Pavilion, Hempstead Town Hall, 1 Washington Street, Hempstead, New York, on the 21st day of January, 2020, at 10:30 o'clock in the forenoon of that day to consider the enactment of a local law to amend Chapter 202 of the code of the Town of Hempstead to INCLUDE and REPEAL "REGULATIONS AND RESTRICTIONS" to limit parking at the following locations: GARDEN CITY SOUTH NASSAU BOULEVARD (TH 565/19) West Side Section 202-14 - ONE HOUR PARKING EXCEPT NO PARKING 3 AM TO 6 AM MONDAY AND THURSDAY - starting at a point 30 feet north of the north curbline of Terrace Avenue north for a distance of 246 feet. NASSAU BOULEVARD (TH 565/19) West Side - ONE HOUR PARKING EXCEPT NO PARKING 3 AM TO 6 AM MONDAY AND THURSDAY - start~ng at a point 381 feet north of the north curbline of Terrace Avenue north for a distance of 192 feet. NASSAU BOULEVARD (TH 565/19) East Side - ONE HOUR PARKING EXCEPT NO PARKING 3 AM TO 6 AM MONDAY AND THURSDAY - starting at a point 76 feet north of the north curbline of Terrace Avenue north for a distance of 157 feet. NASSAU BOULEVARD (TH 565/19) East Side - ONE HOUR PARKING EXCEPT NO PARKING 3 AM TO 6 AM MONDAY AND THURSDAY - starting at a point 403 feet north of the north curbline of Terrace Avenue north for a distance of 176 feet. -

The Carlyle Society Papers

THE CARLYLE SOCIETY SESSION 2013-2014 OCCASIONAL PAPERS 26 • Edinburgh 2013 1 2 President’s Letter 2013-14 will be a year of changes for the Carlyle Society of Edinburgh. Those of you who receive notification of meetings by email will already have had the news that, after many years, we are leaving 11 Buccleuch Place. We have enjoyed the hospitality of Lifelong Learning for decades but they, too, are moving. So we are meeting – for this year – in the seminar room on the first floor of 18 Buccleuch Place. There is one flight of stairs (I used it for decades! It’s not bad) and we will be comfortably housed there. Usual time. The Carlyle Letters are moving steadily towards the completion of the correspondence of Thomas and Jane; with Jane’s death in 1866 we will have published all the known letters between them, and we plan to tidy off the process with some papers from the months immediately following her death, and papers more recently come to light, namely volumes 43-44. The Carlyle Letters Online are also moving steadily to catch up with the published volumes. Volume 40 was celebrated with a public lecture in Autumn 2012; volume 41 will appear in printed form in about a month’s time, and the materials for volume 42 will be going to Duke in about a week’s time from when these words are written. We are grateful to the English Literature department for access to our new premises in 18 Buccleuch Place; to Andy Laycock of the University’s printing department for Herculean efforts with our annual papers; to those members who now accept their annual mailing in electronic form, a huge saving in time and money. -

Malecka, Joanna Aleksandra (2013) Between Herder and Luther

Malecka, Joanna Aleksandra (2013) Between Herder and Luther: Carlyle’s literary battles with the devil in his Jean Paul Richter Essays (1827, 1827, 1830) and in Sartor Resartus (1833-34). MPhil(R) thesis http://theses.gla.ac.uk/4343/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Between Herder and Luther: Carlyle’s literary battles with the devil in his Jean Paul Richter Essays (1827, 1827, 1830) and in Sartor Resartus (1833-34). A thesis presented for the degree of Master of Philosophy in the Department of Scottish Literature at the University of Glasgow, November 2012 by Joanna Aleksandra Malecka. (c) Joanna Malecka 2012 If you want to see his monument, look at this dunghill. Thomas Carlyle, Sartor Resartus1 1 Thomas Carlyle, Sartor Resartus in Sartor Resartus, Heroes and Hero Worship, Past and Present (London: Ward, Lock & Bowden) undated c1900, p. 93: ‘Si monumentum quaeris, fimetum adspice’; subsequently referred to as SR. 1 Abstract ‘Between Herder and Luther: Carlyle’s literary battles with the devil in his Jean Paul Richter essays (1827, 1827, 1830) and in Sartor Resartus (1833-34)’ examines the position allocated to the representation of the devil in Carlyle’s early religious thought. -

Alexis De Tocqueville, John Stuart Mill and Thomas Carlyle on Democracy

ALEXIS DE TOCQUEVILLE, JOHN STUART MILL AND THOMAS CARLYLE ON DEMOCRACY GEORGE HENRY WILLIAM CURRIE SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 1 STATEMENT OF ORIGINALITY I, George Henry William Currie, confirm that the research included within this thesis is my own work or that where it has been carried out in collaboration with, or supported by others, that this is duly acknowledged below and my contribution indicated. Previously published material is also acknowledged below. I attest that I have exercised reasonable care to ensure that the work is original, and does not to the best of my knowledge break any UK law, infringe any third party’s copyright or other Intellectual Property Right, or contain any confidential material. I accept that the College has the right to use plagiarism detection software to check the electronic version of the thesis. I confirm that this thesis has not been previously submitted for the award of a degree by this or any other university. The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. Signature: Date: 2 ABSTRACT The aim of this thesis is to examine and compare the thought of Alexis de Tocqueville, John Stuart Mill and Thomas Carlyle on modern democracy. Throughout their works, Tocqueville, Mill and Carlyle showed a profound engagement with the phenomenon of democracy in their era. It was the crux around which their wider reflections on the period revolved. -

Basques in the San Francisco Bay Area

1FESP+0JBS[BCBMXBTCPSOBOESBJTFE 6SB[BOEJCJMEVNBLNVOEVBO[FIBS JO#JMCBPBOEIBTTQFOUNVDIPGIJTMJGF EBVEFOFVTLBMFUYFOBHVTJFOFO CFUXFFO UIF #BTRVF $PVOUSZ *SFMBOE IJTUPSJBKBTPU[FBEVIFMCVSV BOEUIF6OJUFE4UBUFT)FIPMETB1I% BU[FSSJSBUVUBLPFVTLBMEVOPO JO#BTRVF4UVEJFT1PMJUJDBM4DJFODFGSPN CJ[JQFOFUBOPJOBSSJUVUB UIF6OJWFSTJUZPG/FWBEB 3FOP BOEJTB 63";"/%* 7JTJUJOH 3FTFBSDI 4DIPMBS BU UIF 0SBM )JTUPSZ 1SPHSBN 6OJWFSTJUZ PG /FWBEB 3FOP "NPOH IJT QVCMJDBUJPOT BSF -B -BDPMFDDJwO6SB[BOEJ ²BMMFOEF *EFOUJEBE 7BTDB FO FM .VOEP #BTRVF MPTNBSFT³ SFDPHFMBIJTUPSJBEFMPT *EFOUJUZ JO UIF8PSME BOE " $BOEMF JO QSJODJQBMFTDFOUSPTWBTDPTEFMNVOEP UIF /JHIU #BTRVF 4UVEJFT BU UIF CBTBEBFOMPTUFTUJNPOJPTEFQSJNFSB 6OJWFSTJUZPG/FWBEB )F JT NBOPEFBRVnMMPTRVFFNJHSBSPO DVSSFOUMZBXBJUJOHUIFQVCMJDBUJPOPGIJT WPMVNF FOUJUMFE 5IF #BTRVF %JBTQPSB 4"/'3"/$*4$0 8FCTDBQF 5IF6SB[BOEJ ²GSPNPWFSTFBT³ $PMMFDUJPODPNQJMFTUIFIJTUPSZPGUIF NPTUJNQPSUBOU#BTRVF$MVCTBMMPWFS UIF8PSME CBTFEPOGJSTUIBOE NFNPSJFTPGUIPTFXIPFNJHSBUFE -BDPMMFDUJPO6SB[BOEJ ²PVUSFNFS³ SFDFVJMMFMFTIJTUPJSFTEFTQSJODJQBVY DFOUSFTCBTRVFTEVNPOEFCBTnTTVS 4"/'3"/$*4$0 MFTUnNPJHOBHFTEJSFDUTEFDFVYRVJ nNJHSoSFOU *4#/ Chaleco Urazandi 23.indd 1 24/4/09 09:47:42 UUrazandirazandi 2233 SSanan Francisco.inddFrancisco.indd 2 33/4/09/4/09 112:25:402:25:40 23 GARDENERS OF IDENTITY: BASQUES IN THE SAN FRANCISCO BAY AREA by Pedro J. Oiarzabal LEHENDAKARITZA PRESIDENCIA Eusko Jaurlaritzaren Argitalpen Zerbitzu Nagusia Servicio Central de Publicaciones del Gobierno Vasco Vitoria-Gasteiz, 2009 UUrazandirazandi 2233 SSanan Francisco.inddFrancisco.indd -

English Versions of Foreign Names

ENGLISH VERSIONS OF FOREIGN NAMES Compiled by: Paul M. Kankula ( NN8NN ) at [email protected] in May-2001 Note: For non-profit use only - reference sources unknown - no author credit is taken or given - possible typo errors. ENGLISH Czech. French German Hungarian Italian Polish Slovakian Russian Yiddish Aaron Aron . Aaron Aron Aranne Arek Aron Aaron Aron Aron Aron Aron Aronek Aronos Abel Avel . Abel Abel Abele . Avel Abel Hebel Avel Awel Abraham Braha Abram Abraham Avram Abramo Abraham . Abram Abraham Bramek Abram Abrasha Avram Abramek Abrashen Ovrum Abrashka Avraam Avraamily Avram Avramiy Avarasha Avrashka Ovram Achilies . Achille Achill . Akhilla . Akhilles Akhilliy Akhylliy Ada . Ada Ada Ara . Ariadna Page 1 of 147 ENGLISH VERSIONS OF FOREIGN NAMES Compiled by: Paul M. Kankula ( NN8NN ) at [email protected] in May-2001 Note: For non-profit use only - reference sources unknown - no author credit is taken or given - possible typo errors. ENGLISH Czech. French German Hungarian Italian Polish Slovakian Russian Yiddish Adalbert Vojta . Wojciech . Vojtech Wojtek Vojtek Wojtus Adam Adam . Adam Adam Adamo Adam Adamik Adamka Adi Adamec Adi Adamek Adamko Adas Adamek Adrein Adas Adamok Damek Adok Adela Ada . Ada Adel . Adela Adelaida Adeliya Adelka Ela AdeliAdeliya Dela Adelaida . Ada . Adelaida . Adela Adelayida Adelaide . Adah . Etalka Adele . Adele . Adelina . Adelina . Adelbert Vojta . Vojtech Vojtek Adele . Adela . Page 2 of 147 ENGLISH VERSIONS OF FOREIGN NAMES Compiled by: Paul M. Kankula ( NN8NN ) at [email protected] in May-2001 Note: For non-profit use only - reference sources unknown - no author credit is taken or given - possible typo errors. ENGLISH Czech. French German Hungarian Italian Polish Slovakian Russian Yiddish Adelina . -

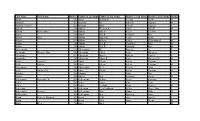

Last Name First Name Birth Yrfather's Last Name Father's

Last Name First Name Birth YrFather's Last Name Father's First Name Mother's Last Name Mother's First Name Gender Aaron 1907 Aaron Benjaman Shields Minnie M Aaslund 1893 Aaslund Ole Johnson Augusta M Aaslund (Twins) 1895 Aaslund Oluf Carlson Augusta F Abbeal 1906 Abbeal William A Conlee Nina E M Abbitz Bertha Dora 1896 Abbitz Albert Keller Caroline F Abbot 1905 Abbot Earl R Seldorff Rose F Abbott Zella 1891 Abbott James H Perry Lissie F Abbott 1896 Abbott Marion Forder Charolotta M M Abbott 1904 Abbott Earl R Van Horn Rose M Abbott 1906 Abbott Earl R Silsdorff Rose M Abercrombie 1899 Abercrombie W Rogers A F Abernathy Marjorie May 1907 Abernathy Elmer Scott Margaret F Abernathy 1892 Abernathy Wm A Roberts Laura J F Abernethy 1905 Abernethy Elmer R Scott Margaret M M Abikz Louisa E 1902 Abikz Albert Keller Caroline F Abilz Charles 1903 Abilz Albert Keller Caroline M Abircombie 1901 Abircombie W A Racher Allos F Abitz Arthur Carl 1899 Abitz Albert Keller Caroline M Abrams 1902 Abrams L E Baker May F Absher 1905 Absher Ben Spillman Zoida M Achermann Bernadine W 1904 Ackermann Arthur Krone Karolina F Acker 1903 Acker Louis Carr Lena F Acker 1907 Acker Leyland Ryan Beatrice M Ackerman 1904 Ackerman Cecil Addison Willis Bessie May F Ackermann Berwyn 1905 Ackermann Max Mann Dolly M Acklengton 1892 Achlengton A A Riacting Nattie F Acton Rebecca Elizabeth 1891 Acton T M Cox Josie E F Acton 1900 Acton Chas Payne Minnie M Adair Elles 1906 Adair Adel M Last Name First Name Birth YrFather's Last Name Father's First Name Mother's Last Name Mother's -

The Works of Thomas Carlyle

This book is DUF'On *he last date stamped below SOUTHERN BRANCH, IIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA. LIBRARY, CENTENARY EDITION THE WORKS OF THOMAS CARLYLE I N T H I It T Y V O L U M E S VOL. XI THE LIFE OF JOHN STERLING THOMAS CARLYLE THE LIFE OF JOHN STERLING IN ONE VOLUME « - • - • 1 » , Originally published 1851 £ 3 k v. W CONTENTS INTRODUCTION vu PART I CHAP. I. Introductory .... vi THE LIFE OF JOHN STERLING CHAP. PAGE IV. To Bordeaux ISO V. To Madeira 143 VI. Literature: The Sterling Club . .154 160 VII. Italy ... 3 ...... PART III I. Clifton 1§ 3 II. Two Winters 197 208 III. Falmouth : Poems 224 IV. Naples : Poems V. Disaster on Disaster 234 248 VI. Ventnor : Death .....•• VII. Conclusion 262 Summary ......••• 269 Index .,,....••• 277 PORTRAIT OF JOHN STERLING . frontispiece INTRODUCTION If Mr. Froude was right in his conjecture as to the ci*eative to origin of the Life of Sterling, the world owes more a country house symposium than it is generally aware of. For it is believed by Carlyle's biographer that the final impulse to this work was derived from a conversation at Lord Ashburton's, in which Carlyle and Bishop Thirlwall became involved in an 'animated theological discussion/ carried on in the presence of several other literary notables whom he names. What was its precise subject he does its not tell us ; result, that is, its immediate result, we do not need to be told. It ended, beyond all possible doubt, in leaving the disputants exactly where they were at starting. -

French Revolution and the Trial of Marie Antoinette Background Guide Table of Contents

French Revolution And The Trial Of Marie Antoinette Background Guide Table of Contents Letter from the Chair Letter from the Crisis Director Committee Logistics Introduction to the Committee Introduction to Topic One History of the Problem Past Actions Taken Current Events Questions to Consider Resources to Use Introduction to Topic Two History of the Problem Past Actions Taken Current Events Questions to Consider Resources to Use Bibliography Staff of the Committee Chair: Peyton Coel Vice Chair: Owen McNamara Crisis Director: Hans Walker Assistant Crisis Director: Sydney Steger Coordinating Crisis Director: Julia Mullert Under Secretary General Elena Bernstein Taylor Cowser, Secretary General Neha Iyer, Director General Letter from the Chair Hello Delegates! I am so thrilled to welcome you all to BosMUN XIX. For our returning delegates, welcome back! For our new delegates, we are so excited to have you here and hope you have an amazing time at the conference. My name is Peyton Coel and I am so honored to be serving as your Chair for this incredible French Revolution committee. I’m a freshman at Boston University double majoring in History and International Relations. I’m from the frigid Champlain Valley in Vermont, so the winters here in Boston are no trouble at all for me. When I’m not rambling on about fascinating events in history or scouring the news for important updates, you can find me playing club water polo or swimming laps in the lovely FitRec pool, exploring the streets of Boston (Copley is my favorite place to go), and painting beautiful landscapes with the help of Bob Ross. -

The Hero As Man of Letters”

“THE HERO AS MAN OF LETTERS”: INTELLECTUAL POLITICS AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE ROMANTIC EPIC By Copyright 2013 Eric S. Hood Ph.D., University of Kansas 2013 Submitted to the Department of English and the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy __________________________________ Chairperson: Ann Rowland Committee Members:__________________________________ Philip Barnard __________________________________ Anna Neill __________________________________ Dorice Elliott __________________________________ Leslie Tuttle Date Defended: 08/30/2013 ii The Dissertation Committee for Eric S. Hood certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis/dissertation: “THE HERO AS MAN OF LETTERS”: INTELLECTUAL POLITICS AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE ROMANTIC EPIC __________________________________ Ann Rowland _______________________08/30/2013__ Date Approved iii Abstract Although the thirty years from 1794 to 1824 saw the production of more epic poetry than any other period in British literary history, the epic’s function within the culture of Romanticism remains largely misunderstood and neglected. The problem in theorizing the Romantic epic stems from the uncommon diversity of epic performances during this period and from the epic’s sudden reappearance after a long period of apparent dormancy in the eighteenth century. When the Romantic epic is defined, however, not as poetic form but as a repeated political act, the epic’s eighteenth-century